The Effectiveness of Cooperative Learning Teams Using the Bcubetm Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faculty Work: Moving Beyond the Paradox

FACULTY WORK: MOVING BEYOND THE PARADOX OF AUTONOMY AND COLLABORATION Mark A. Hower A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Ph.D. in Leadership and Change Program at Antioch University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January, 2012 This is to certify that the Dissertation entitled: EXPLORING FACULTY WORK: MOVING BEYOND THE PARADOX OF AUTONOMY AND COLLABORATION prepared by Mark A. Hower is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of in Leadership and Change. Approved by: Chair, Jon F. Wergin, Ph.D. date ________________________________________________________________________ Committee Member, Alan E. Guskin, Ph.D. date ________________________________________________________________________ Committee Member, Carol Baron, Ph.D. date ________________________________________________________________________ External Reader, Ann E. Austin, Ph.D. date ©Copyright by Mark A. Hower, 2012 All Rights Reserved Acknowledgment My heart has been filled by the kindness and support extended to me while engaged in this dissertation. Though words alone cannot fully convey the gratitude I feel, I wish to try nevertheless. First, I am grateful to the faculty, staff, and administrators who participated in this study or helped make it possible. Thank you for taking time to provide such thoughtful responses and for your encouragement of my work. Dr. John Wergin, I am deeply grateful for the thoughtful guidance you provided as chair of my dissertation committee. Your passion for research is contagious. I have grown as a person and scholar through your deft ability to both challenge and affirm. Thank you also for the gracious space to explore, learn from missteps, and find my own voice. -

Description of Feelings, (8) Emotional States,(9) Feedback, (10)

0 DOCUIENT NEMER ED '14.8..355 1111 005 111166 A t AUTHOR 'Buel, Sue; Hosfordi, Charles Ttiziag Interpersonal, Communications Works hop. ., 'INSTITUTpli Ngrthwest regional Educational Lab., Portland,... ore g. * 4 PUB DATE, .Jul 12 . NOTE 83p..; Several piges have nar4inal. legibility. EDRS PRICE . 4I r-$0:83.tic-$11.67 Plus Postagi.', 0 DESCRIPTORS *Comatinication Skills; 'Instructional Biteriils; *Intercoismunicatiow; *Interpersonal Competence; *Interpersonal .12elationihip; -Librarians; Professional 0, .... Continuing Education: ASkill.Develop,nts. ' . 1 4. , Workshops a . 4 . ,- .. A ,.. 1 OSTRACT -- The major purpose, of anr .intrpersioaI communications waikshop is to provide participants the 'opportunity to Acquire knowledge andpractice skills in face-,to-tface.coimunidation, individual communicating Style, group and organixatiopal factors which affect communication, and continued improvement of individual communication skills.' The exercises in this document are designed for- use-by library personnek. in a,series of theory and.practice sessions on interpersonal communications. Topics includes (1) the degree of congruence between a person os intentions anti,-tbe effect produced,(2) paraphrasing ,(3) handling misunderstandings,(4) nonverbal behavior, (5) behavior description, (6) defensive communication, (7),. description of feelings, (8) emotional states,(9) feedback, (10) ,.. interpersonal effect, (11) matching behavior, (12). norms, (13) grotp processes;(14) .goals, and (15) power wand infludnce. Mr . ' . .2* . , *******************************************************o*************** -

A Study of Ego-Strength As It Relates to Homogeneous-Heterogeneous Grouping in Group Process" (1976)

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1976 A Study of Ego-Strength as It Relates to Homogeneous- Heterogeneous Grouping in Group Process Evelyn Evans Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Evans, Evelyn, "A Study of Ego-Strength as It Relates to Homogeneous-Heterogeneous Grouping in Group Process" (1976). Dissertations. 1523. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1523 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1976 Evelyn Evans A STUDY OF EGO-STRENGTH AS IT RELATES TO HOMOGENEOUS-HETEROGENEOUS GROUPING IN GROUP PROCESS by Evelyn Evans A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 1976 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the entire staff and my fellow students for the support, guidance, and help I received during my study at Loyola. To Dr. John Wellington who has extended warmth, understanding, encourage ment, and continual assistance as my advisor and the chairman of this committee, a very special thank you. To Dr. Judy Lewis of San Francisco Univers:i.ty who not only served as teacher, advisor, and a member of my eommittoe, but shared her frienduhip, a note o!' gratitude ln uxtunuuti. -

Psychodynamics of Drug Dependence, 12

PSYCHODYNAMICS OF DRUG DEPENDENCE US DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION, AND WELFARE • Public Health Service • Alcohol, Drug Abuse. and Menial Health Administration PSYCHODYNAMICS OF DRUG DEPENDENCE Editors Jack D. Blaine, M.D. Demetrios A. Julius, M.D. Division of Research National Institute on Drug Abuse May 1977 NIDA Research Monograph 12 U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington. D.C. 20402 Stock No. 017-024-00642-4 The NIDA Research Monograph series is prepared by the Division of Research of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Its primary objective is to provide critical re- views of research problem areas and techniques, the content of state-of-the-art conferences, integrative research reviews and significant original research. Its dual publication emphasis is rapid and targeted dissemination to the scientific and professional community. Editorial Advisory Board Avram Goldstein, M.D. Addiction Research Foundation Palo Alto, California Jerome Jaffe, M.D. College of Physicians and Surgeons Columbia University. New York Reese T. Jones, M.D. Langley Porter Neuropsychiatric Institute University of California San Francisco. California William McGlothlin, Ph.D. Department of Psychology, UCLA Los Angeles. California Jack Mendelson, M.D. Alcohol and Drug Abuse Research Center Harvard Medical School McLean Hospital Belmont. Massachusetts Helen Nowlis, Ph.D. Office of Drug Education. DHEW Washington. DC. Lee Robins, Ph.D. Washington University School of Medicine St Louis. Missouri NIDA Research Monograph series Robert DuPont, M.D. DIRECTOR, NIDA William Pollin, M.D. -

Perception of Social Loafing, Conflict, and Emotion in the Process of Group Development

PERCEPTION OF SOCIAL LOAFING, CONFLICT, AND EMOTION IN THE PROCESS OF GROUP DEVELOPMENT A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY MIN ZHU IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DR. DEAN E. HEWES, ADVISER AUGUST, 2013 © Min Zhu 2013 i ABSTRACT This study was conducted for two purposes. The first was to find out trend patterns for perceived social loafing, the four types of intra-group conflict (i.e., task, relationship, logistic, and contribution), and positive vs. negative emotions, in the group’s developmental process. The second was to explain how perceived social loafing was aroused based upon the knowledge of intra-group conflicts and negative emotions. Participants (n = 164) were required to report their personal perception of social loafing, intra-group conflicts, emotions (i.e., anger, fatigue, vigor, confusion, tension, depression, and friendliness), and the stage of group development, in their current small group interaction. Four major findings emerged out of the data analysis. First, perceived social loafing, relationship conflict, logistical conflict, contribution conflict, and negative emotions all followed a reversed V-shaped trend of development with their respective peaks observed at Stage 2 (i.e., Counterdependency and Fight), whereas task conflict followed a slanted, N-shaped, but relatively stable, trend over the course of group development. Second, positive emotions developed in a V-shaped trend pattern, wherein the lowest point was observed at Stage 2 and highest point at Stage 4 (i.e., Work). Third, the perception of social loafing was found to be directly and positively influenced by contribution conflict and negative emotions, while task conflict, logistical conflict, and relationship conflict did not have direct positive effects on perceived social loafing. -

Get Your PDF Book

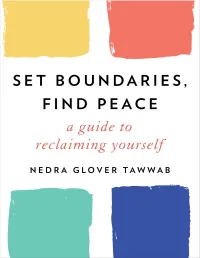

Advance Praise for Set Boundaries, Find Peace “This is the boundary bible. Nedra teaches us not only how to set healthy boundaries but to be clear about our feelings and intentions. Finding peace requires showing up—Nedra has written the blueprint on how to not only show up but also do the work.” —Alexandra Elle, author of After the Rain “If you want the most comprehensive, relevant, and relatable guide to setting boundaries, speaking your needs, and living a more peaceful life, Nedra Tawwab’s book on boundaries is for you.” —Sheleana Aiyana, author and founder of Rising Woman “The book on boundaries we’ve all been waiting for! Nedra Tawwab offers clarity and direction with grace and compassion on a topic often discussed but rarely integrated. If you’re ready to live in alignment and shift your relationship with self and others, Set Boundaries, Find Peace is your next must-read.” —Vienna Pharaon, LMFT, founder of Mindful Marriage & Family Therapy “Set Boundaries, Find Peace breaks down the what, why, and how of boundaries in a clear and compassionate way, leaving you confident, empowered, and prepared to tackle those tough conversations.” —Melissa Urban, cofounder and CEO of Whole30 “Without healthy boundaries, we aren’t able to fully live the life we want to live. This empowering book provides a powerful road map for establishing expectations and personal limits so that you can live your life with the safety, respect, and self-actualization that you deserve.” —Scott Barry Kaufman, PhD, host of The Psychology Podcast and author of Transcend “Set Boundaries, Find Peace is a down-to-earth and practical guide on fully realizing your potential and giving yourself the freedom you deserve by clearly setting healthy boundaries in your personal and professional life, friendships, and relationships. -

Developmental Differences in Individuals with Borderline Personality Disorder

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1985 Developmental differences in individuals with borderline personality disorder. Dawn E. Balcazar University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Balcazar, Dawn E., "Developmental differences in individuals with borderline personality disorder." (1985). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2225. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2225 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEVELOPMENTAL DIFFERENCES IN INDIVIDUALS WITH BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER A Thesis Presented by DAWN BALCAZAR Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May 1985 Psychology DEVELOPMENTAL DIFFERENCES IN INDIVIDUALS WITH BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER A Thesis Presented By DAWN E. BALCAZAR Approved as to style and content by: Howard Gadlin, Chairperson Department of Psychology ii . ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Each of the three members of my committee has been enormously helpful in the planning and carrying through of this project over the last few years. In the initial stages, Dr. Harold Jarmon was particu- larly generous with his time and greatly contributed to my being able to more clearly define my interests and plan a study that could real- istically be done. Dr. Howard Gadlin was very patient, supportive and readily accessible when needed. I especially appreciated his availability when I had many questions and needs for assistance during the final writing of the thesis. -

Practice Guidelines for Group Psychotherapy

PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY THE AMERICAN GROUP PSYCHOTHERAPY ASSOCIATION SCIENCE TO SERVICE TASK FORCE 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ......................................................................................................................... Page 2 Introduction.................................................................................................................. Page 3 Text: Science to Service Task Force Members................................................................... Page 6 Creating Successful Therapy Groups......................................................................... Page 7 Therapeutic Factors and Therapeutic Mechanisms.................................................... Page 12 Selection of Clients.................................................................................................... Page 19 Preparation and Pre-Group Training.......................................................................... Page 25 Group Development................................................................................................... Page 30 Group Process ............................................................................................................ Page 36 Therapist Interventions .............................................................................................. Page 41 Reducing Adverse Outcomes and the Ethical Practice of Group Psychotherapy............................................................................... Page 47 Concurrent Therapies................................................................................................ -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zaab Road Ann Arbor

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from die document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

A Theory of Moral Objectivity' Moral Contents Page Objectivity: Quick Links to a Theory of Moral Objectivity Other Sections (Chapter 8 - Contents the Ethics of the 1

A Theory of moralobjectivity.net: home page 'A Theory of Moral Objectivity' Moral contents page Objectivity: quick links to A Theory of Moral Objectivity other sections (Chapter 8 - Contents The ethics of the 1. introduction Middle Way) 2a. Psychology of belief By Robert M. Ellis, originally written as a Ph.D. thesis 'A Buddhist theory of moral objectivity' 2b. Heuristic in 2001. This html version copyright 2008. process A hardcopy paperback book of this thesis is 2c. Psychology & now available from lulu.com and also on philosophy Amazon, price UK£25 (or equivalent). This relatively high cost is necessary because it is A4 3ab. Eternalism size and has 487 pages (296,000 words). This print version includes an index. 3cd. Plato 3e. Stoicism 3f. Christianity A downloadable pdf version of this thesis is available from the British Library at http://ethos.bl.uk (you will need to search the original title 'A 3g. Kant Buddhist theory of moral objectivity', and register with the ethos site, but registration is open and the download pdf is free for researchers). 3h. Hegel Alternatively you can download a pdf for a small cost from lulu.com. 3i. Marx Join discussion or ask questions on any aspect of the thesis on the new phpbb discussion board 3j. Schopenhauer 3kl. Utilitarianism This page contains the whole of Chapter 8. Alternatively 4a. Nihilism click on the links below for specific sections: 4b. Scepticism & Aristotle 8a. Moral Authority (how deontological sources of moral information can be used in a provisional way) 4c. Hume 8b. Issues in the application of precepts (discussion of the practical 4d. -

Narcissistic Vulnerability in the Hyperaggressive Child: the Disregarded (Unloved, Uncared-For) Self

PSYCHOANALYTIC PSYCHOLOGY, 1986, 3(1), 39-80 Copyright © 1986, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Narcissistic Vulnerability in the Hyperaggressive Child: The Disregarded (Unloved, Uncared-for) Self Brent Willock, Ph.D. C. M. Hincks Treatment Centre Efforts to treat hyperaggressive children frequently break down in a manner which reinforces the feeling that these children are beyond the reach of psycho- therapeutic intervention. This study was undertaken in an attempt to elucidate the essential nature of the psychopathology of these children in order to provide a better foundation for the therapeutic enterprise. One finding was that much of their violent behavior is related to underlying narcissistic vulnerability, one facet of which is here termed the disregarded self. Much of the child's aggres- sive, antisocial behavior can be understood as an attempt to cope with and de- fend against the hurt, the anger, and the anxiety associated with this aspect of self-structure. Origins of the disregarded self are considered from a psychody- namic perspective integrating child-rearing, sociocultural, and psycho- biological factors. The implications of this concept for individual psychother- apy and milieu treatment are discussed. INTRODUCTION This report concerns a population of children whose violent, unmanageable behavior has earned them considerable notoriety in both educational and clinical milieus. Their expressive and defensive style, replete with loud threats and sudden, wildly destructive outbursts, typically leads to increasingly nega- tive reputations in their communities, and at a young age they may already be well known to local authorities. Less well known is what to do about them, particularly how to really help them. -

How Clinicians Feel About Working with Spouses of the Chronically Ill

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Touro College and University System Touro Scholar NYMC Faculty Publications Faculty 9-1-2015 How Clinicians Feel about Working with Spouses of the Chronically Ill Douglas Ingram New York Medical College Follow this and additional works at: https://touroscholar.touro.edu/nymc_fac_pubs Part of the Psychiatry and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Ingram, D. (2015). How Clinicians Feel about Working with Spouses of the Chronically Ill. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 43 (3), 378-395. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2015.43.3.378 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty at Touro Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYMC Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Touro Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INGRAM WORKING WITH SPOUSES OF THE CHRONICALLY ILL How Clinicians Feel about Working with Spouses of the Chronically Ill Douglas H. Ingram Abstract: Clinicians who provide psychotherapy to spouses or partners of the chronically ill were solicited through listserves of psychodynamic and other organizations. The current report excluded those therapists working with spouses of dementia patients. Interviews were conducted with clinicians who responded. The interviews highlight the challenges commonly encountered by psychotherapeutic work with this cohort of therapy patients. A comparison is drawn that shows both overlap and distinctions between the experiences of those therapists engaging with spouses of chronically ill patients without a dementing process and those working with spouses of chronically ill patients who do suffer from a dementing process.