PDF (Phd Thesis Vostermans)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cool Trombone Lover

NOVEMBER 2013 - ISSUE 139 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM ROSWELL RUDD COOL TROMBONE LOVER MICHEL • DAVE • GEORGE • RELATIVE • EVENT CAMILO KING FREEMAN PITCH CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK CITY FEATURED ARTISTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm RESIDENCIES / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Fri & Sat, Nov 1 & 2 Wed, Nov 6 Sundays, Nov 3 & 17 GARY BARTZ QUARTET PLUS MICHAEL RODRIGUEZ QUINTET Michael Rodriguez (tp) ● Chris Cheek (ts) SaRon Crenshaw Band SPECIAL GUEST VINCENT HERRING Jeb Patton (p) ● Kiyoshi Kitagawa (b) Sundays, Nov 10 & 24 Gary Bartz (as) ● Vincent Herring (as) Obed Calvaire (d) Vivian Sessoms Sullivan Fortner (p) ● James King (b) ● Greg Bandy (d) Wed, Nov 13 Mondays, Nov 4 & 18 Fri & Sat, Nov 8 & 9 JACK WALRATH QUINTET Jason Marshall Big Band BILL STEWART QUARTET Jack Walrath (tp) ● Alex Foster (ts) Mondays, Nov 11 & 25 Chris Cheek (ts) ● Kevin Hays (p) George Burton (p) ● tba (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Captain Black Big Band Doug Weiss (b) ● Bill Stewart (d) Wed, Nov 20 Tuesdays, Nov 5, 12, 19, & 26 Fri & Sat, Nov 15 & 16 BOB SANDS QUARTET Mike LeDonne’s Groover Quartet “OUT AND ABOUT” CD RELEASE LOUIS HAYES Bob Sands (ts) ● Joel Weiskopf (p) Thursdays, Nov 7, 14, 21 & 28 & THE JAZZ COMMUNICATORS Gregg August (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Gregory Generet Abraham Burton (ts) ● Steve Nelson (vibes) Kris Bowers (p) ● Dezron Douglas (b) ● Louis Hayes (d) Wed, Nov 27 RAY MARCHICA QUARTET LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES / 11:30 - Fri & Sat, Nov 22 & 23 FEATURING RODNEY JONES Mon The Smoke Jam Session Chase Baird (ts) ● Rodney Jones (guitar) CYRUS CHESTNUT TRIO Tue Cyrus Chestnut (p) ● Curtis Lundy (b) ● Victor Lewis (d) Mike LeDonne (organ) ● Ray Marchica (d) Milton Suggs Quartet Wed Brianna Thomas Quartet Fri & Sat, Nov 29 & 30 STEVE DAVIS SEXTET JAZZ BRUNCH / 11:30am, 1:00 & 2:30pm Thu Nickel and Dime OPS “THE MUSIC OF J.J. -

Militia Politics

INTRODUCTION Humboldt – Universität zu Berlin Dissertation MILITIA POLITICS THE FORMATION AND ORGANISATION OF IRREGULAR ARMED FORCES IN SUDAN (1985-2001) AND LEBANON (1975-1991) Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil) Philosophische Fakultät III der Humbold – Universität zu Berlin (M.A. B.A.) Jago Salmon; 9 Juli 1978; Canberra, Australia Dekan: Prof. Dr. Gert-Joachim Glaeßner Gutachter: 1. Dr. Klaus Schlichte 2. Prof. Joel Migdal Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 18.07.2006 INTRODUCTION You have to know that there are two kinds of captain praised. One is those who have done great things with an army ordered by its own natural discipline, as were the greater part of Roman citizens and others who have guided armies. These have had no other trouble than to keep them good and see to guiding them securely. The other is those who not only have had to overcome the enemy, but, before they arrive at that, have been necessitated to make their army good and well ordered. These without doubt merit much more praise… Niccolò Machiavelli, The Art of War (2003, 161) INTRODUCTION Abstract This thesis provides an analysis of the organizational politics of state supporting armed groups, and demonstrates how group cohesion and institutionalization impact on the patterns of violence witnessed within civil wars. Using an historical comparative method, strategies of leadership control are examined in the processes of organizational evolution of the Popular Defence Forces, an Islamist Nationalist militia, and the allied Lebanese Forces, a Christian Nationalist militia. The first group was a centrally coordinated network of irregular forces which fielded ill-disciplined and semi-autonomous military units, and was responsible for severe war crimes. -

Devising New European Policies to Face the Arab Spring

Papers presented 1 to Conference I and II on Thinking Out of the Box: Devising New European Policies to Face the Arab Spring Edited by: Maria do Céu Pinto Lisboa 2014 With the support of the LLP of the European Union 2 Table of Contents Introduction 4 EU´s Policy Responses: Exploring the Progress and Shortcomings 6 The EU “Paradigmatic Policy Change” in Light of the Arab Spring: A Critical Exploration of the “Black Box” 7 Iole Fontana Assessing European Mediterranean Policy: Success Rather than Failure 18 Marie-Luise Heinrich-Merchergui, Temime Mechergui, and Gerhard Wegner Searching For A “EU Foreign Policy” during the Arab Spring – Member States’ Branding Practices in Libya in the Absence of a Common Position 41 Inez Weitershausen The EU Attempts at Increasing the Efficiency of its Democratization Efforts in the Mediterranean Region in the Aftermath of the Arab Spring 53 Anastasiia Kudlenko The Fall of Authoritarianism and the New Actors in the Arab World 62 The Arab Uprisings and its Impact on Islamist actors 63 Sandra L. Costa The Arab Uprisings through the Eyes of Young Arabs in Europe 75 Valeria Rosato and Pina Sodano Social Networking Websites and Collective Action in the Arab Spring. Case study: Bahrain 85 Seyed Hossein Zarhani The Contradictory Position of the EU towards Political Islam and the New Rapprochement to Islamist Governments 100 Sergio Castaño Riaño THE NEW SECURITY AND GEOPOLITICAL CONTEXT 110 3 Lebanon and the “Arab Spring” 111 Alessandra Frusciante Sectarianism and State Building in Lebanon and Syria 116 Bilal Hamade Civil-Military Relations in North African Countries and Their Challenges 126 Mădălin-Bogdan Răpan Turkey’s Potential Role for the EU’s Approach towards the Arab Spring: Benefits and Limitations 139 Sercan Pekel Analyzing the Domestic and International Conflict in Syria: Are There Any Useful Lessons from Political Science? 146 Jörg Michael Dostal Migration Flows and the Mediterranean Sea. -

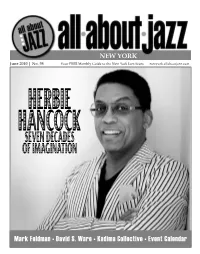

June 2010 Issue

NEW YORK June 2010 | No. 98 Your FREE Monthly Guide to the New York Jazz Scene newyork.allaboutjazz.com HERBIE HANCOCKSEVEN DECADES OF IMAGINATION Mark Feldman • David S. Ware • Kadima Collective • Event Calendar NEW YORK Despite the burgeoning reputations of other cities, New York still remains the jazz capital of the world, if only for sheer volume. A night in NYC is a month, if not more, anywhere else - an astonishing amount of music packed in its 305 square miles (Manhattan only 34 of those!). This is normal for the city but this month, there’s even more, seams bursting with amazing concerts. New York@Night Summer is traditionally festival season but never in recent memory have 4 there been so many happening all at once. We welcome back impresario George Interview: Mark Feldman Wein (Megaphone) and his annual celebration after a year’s absence, now (and by Sean Fitzell hopefully for a long time to come) sponsored by CareFusion and featuring the 6 70th Birthday Celebration of Herbie Hancock (On The Cover). Then there’s the Artist Feature: David S. Ware always-compelling Vision Festival, its 15th edition expanded this year to 11 days 7 by Martin Longley at 7 venues, including the groups of saxophonist David S. Ware (Artist Profile), drummer Muhammad Ali (Encore) and roster members of Kadima Collective On The Cover: Herbie Hancock (Label Spotlight). And based on the success of the WinterJazz Fest, a warmer 9 by Andrey Henkin edition, eerily titled the Undead Jazz Festival, invades the West Village for two days with dozens of bands June. -

Intelligence Report FEE5

DIRECTORATE OF INTELLIGENCE Intelligence Report ESAU L: THE FEDAYEEN (Annex to ESAU XLVIII: Fedayeen-- “Men of Sacrifice’y 1 NO 5 FEE5 . WARNING It is to be seen only by perso indoctrinated and authorized to receive// information within the Government to which#hsmitted; its security mwbe maintained in ac- cordance with1 1 \ I I egardless of the advantage d by the Director of Cen .. I A NOTE ON SOURCES This paper relies primarily on clandestine reporting, particularly for the internal structure and operations of the various fedayeen organizations. I The repostlng 1s quite guoa on poiiticdi as-wf the subject such as the maneuverings of the fedayeen groups, their internal disputes, and their ideological and tactical views. However, our information is more scanty on such important matters as the number of i armed men in each group, the sources and mechanics of funding, and details of the sources and methods of delivery of arms shipments to the fedayeen. I H TABLE OF CONTENTS Page FATAH AND THE PALESTINE LIBERATION ORGANIZATION (PLO) Fatah -- Background to February 1969, (I 1: 1 PLO -- Background to February 1969 c. 8 Fatah Takeover of PLO -- February 1969, ~ LI ,11 Fatah Attempts to Control the Palestine Liberation Army (PLA) ~ , 15 Fatah Retains Its Identity, .20 Fatah Tactics and Operations, .24 Fatah Funding s 0 0 3 0 0 ' (I c 0 0 G 0 D 0 0 .26 THE A3IAB NATIONALIST MOVEMENT (ANMI AND ITS FEDAYEEN WINGS ANMo 0 f 0 0 c 0 0 0 c. 0 0 0 0 J li 0 9.0 c c .30 Background on the ANM's Fedayeen Wings, .32 Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP 1 0 C U C 3 0 0 0 G u 0 u (I c c 35 Organization c 0 0 0 0 c 0 0 0 c c 0 3 c 38 Funding, 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 c 0 0 0 0 0 c p 0 42 Popular Democratic Front for Liberatlon of Palestine (PDFLP) Strategy ., .44 Organization ,, .45 Funding, .48 PFLP General Command, , .51 1- I 1- (Contents Con t) . -

City, War and Geopolitics: the Relations Between Militia Political Violence

City, war and geopolitics: the relations between militia political violence and the built environment of Beirut in the early phases of the Lebanese civil war (1975-1976) Sara Fregonese NEWCASTLE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ---------- ----------------- 207 32628 4 ---------------------------- Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D in the School of Geography, Politics and Sociology Newcastle University May 2008 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk ORIGINAL COpy TIGHTLY BOUND IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk . PAGE NUMBERING AS ORIGINAL IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl,uk NO CD/DVD ATIACHED PLEASE APPLY TO THE UNIVERSITY Thesis abstract The thesis deals with the relationships between political violence and the built environment of Beirut during the early phases of the Lebanese civil war (1975-1976). It investigates how the daily practices of urban warfare and the urban built fabric impacted on each other, and specifically how the violent targeting of the built fabric relates to contested discourses of power and identity enacted by the urban militias. The study is the result of residential fieldwork in Beirut, where I held in-depth interviews with former militia combatants, media representatives, academics and practitioners in urban studies and architecture, as well as conducting archival search into bibliographical, visual and microfilm sources in Arabic, English and French. Official geopolitical discourses in international diplomacy about the civil war between 1975 and 1976 focused on nation-state territoriality, and overlooked a number of complex specifications of a predominantly urban conflict. This led occasionally to an oversimplification of the war and of Beirut as chaos. -

Failing to Deal with the Past : What Cost to Lebanon? for Transitional Justice

Cover Image: On left: Ain El Remmaneh, Beirut, February 17, 1990. (Roger Moukarzel) On right: Special Tribunal for Lebanon. (STL) Top of map: Court room scene after four judges were assassinated in Saida, on June 8, 1999. (Annahar) Bottom of map: Chil- dren in Sin el Fil, 1989. (Roger Moukarzel) Design by Edward Beebe LEBANON Failing to Deal with the Past What Cost to Lebanon? January 2014 International Center Failing to Deal with the Past : What Cost to Lebanon? for Transitional Justice Acknowledgments The International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) gratefully acknowledges the support of the European Union (EU), which made this project possible. Dima Smaira would like to thank Maya Mansour and Rami Smaira for their advice and support. ICTJ also thanks Nidal Jurdi for conducting a peer review. About the Authors and Contributors Dima Smaira is a researcher based in Lebanon specializing in Lebanese politics and the study of conflict and security. She is a PhD candidate in international relations at Durham University (UK). She holds an MA in International Affairs from the Lebanese American University. Her areas of specialization include issues relating to human security, stability, conflict, and the transformation of security in Lebanon. Roxane Cassehgari is a research assistant at ICTJ. She received her LL.M. from Columbia Law School, with a specialization in human rights, transitional justice, and international criminal law. She holds a dual law degree from Cambridge University (UK) and Panthéon- Assas (France). International Center for Transitional Justice ICTJ assists societies confronting massive human rights abuses to promote accountability, pursue truth, provide reparations, and build trustworthy institutions. -

Political Party Mapping in Lebanon Ahead of the 2018 Elections

Political Party Mapping in Lebanon Ahead of the 2018 Elections Foreword This study on the political party mapping in Lebanon ahead of the 2018 elections includes a survey of most Lebanese political parties; especially those that currently have or previously had parliamentary or government representation, with the exception of Lebanese Communist Party, Islamic Unification Movement, Union of Working People’s Forces, since they either have candidates for elections or had previously had candidates for elections before the final list was out from the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities. The first part includes a systematic presentation of 27 political parties, organizations or movements, showing their official name, logo, establishment, leader, leading committee, regional and local alliances and relations, their stance on the electoral law and their most prominent candidates for the upcoming parliamentary elections. The second part provides the distribution of partisan and political powers over the 15 electoral districts set in the law governing the elections of May 6, 2018. It also offers basic information related to each district: the number of voters, the expected participation rate, the electoral quotient, the candidate’s ceiling on election expenditure, in addition to an analytical overview of the 2005 and 2009 elections, their results and alliances. The distribution of parties for 2018 is based on the research team’s analysis and estimates from different sources. 2 Table of Contents Page Introduction ....................................................................................................... -

Extreme Matt-Itude Holidaygift Guide Ikue • Ivo • Joel • Rarenoise • Event Mori Perelman Press Records Calendar December 2013

DECEMBER 2013 - ISSUE 140 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM MATT WILSON EXTREME MATT-ITUDE HOLIDAYGIFT GUIDE IKUE • IVO • JOEL • RARENOISE • EVENT MORI PERELMAN PRESS RECORDS CALENDAR DECEMBER 2013 DAVID SANBORN FOURPLAY CLAUDIO RODITI QUARTET SUNDAY BRUNCH RESIDENCY DEC 3 - 8 DEC 10 - 15 TRIBUTE TO DIZZY GILLESPIE DEC 1, 8, 15, 22, & 29 CHRIS BOTTI ANNUAL HOLIDAY RESIDENCY INCLUDING NEW YEAR’S EVE! DEC 16 - JAN 5 JERMAINE PAUL KENDRA ROSS WINNER OF “THE VOICE” CD RELEASE DEC 2 DEC 9 LATE NIGHT GROOVE SERIES RITMOSIS DEC 6 • CAMILLE GANIER JONES DEC 7 • SIMONA MOLINARI DEC 13 • GIULIA VALLE DEC 14 VICKIE NATALE DEC 20 • RACHEL BROTMAN DEC 21 • BABA ISRAEL & DUV DEC 28 TELECHARGE.COM TERMS, CONDITIONS AND RESTRICTIONS APPLY “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK CITY FEATURED ARTISTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm HOLIDAY EVENTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Fri & Sat, Dec 6 & 7 Sun, Dec 15 SMOKE JAVON JACKSON BAND GEORGE BURTON’S CHRISTMAS YULELOG Winter / Spring 2014 Javon Jackson (tenor saxophone) • Orrin Evans (piano) Thu, Dec 19 Santi DeBriano (bass) • Jason Tiemann (drums) “A NAT ‘KING’ COLE CHRISTMAS” SESSIONS Fri & Sat, Dec 13 & 14 ALAN HARRIS QUARTET BILL CHARLAP TRIO COMPACT DISC AND DOWNLOAD TITLES Bill Charlap (piano) • Peter Washington (bass) COLTRANE FESTIVAL / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Kenny Washington (drums) Mon, Dec 23 - Wed, Dec 25 Fri, Sat & Sun, Dec 20, 21 & 22 ERIC ALEXANDER QUARTET RENEE ROSNES QUARTET FEATURING LOUIS HAYES Steve Nelson (vibraphone) • Renee Rosnes (piano) Eric Alexander (tenor saxophone) • Harold Mabern (piano) Peter Washington (bass) • Lewis Nash (drums) John Webber (bass) • Louis Hayes (drums) Thu, Dec 26 - Wed, Jan 1 ERIC ALEXANDER SEXTET ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm FEAT. -

Curios Or Relics List — January 1972 Through April 2018 Dear Collector

Curios or Relics List — January 1972 through April 2018 Dear Collector, The Firearms and Ammunition Technology Division (FATD) is pleased to provide you with a complete list of firearms curios or relics classifications from the previous editions of the Firearms Curios or Relics (C&R) List, ATF P 5300.11, combined with those made by FATD through April 2018. Further, we hope that this electronic edition of the Firearms Curios or Relics List, ATF P 5300.11, proves useful for providing an overview of regulations applicable to licensed collectors and ammunition classified as curios or relics. Please note that ATF is no longer publishing a hard copy of the C&R List. Table of Contents Section II — Firearms classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. ............................................................................................1 Section III — Firearms removed from the provisions of the National Firearms Act and classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. .......................................................................................................................................................23 Section IIIA —Firearms manufactured in or before 1898, removed from the provisions of the National Firearms Act and classified as antique firearms not subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. ..............................................................................65 Section IV — NFA firearms classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 26 U.S.C. Chapter 53, the National Firearms Act, and 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, the Gun Control Act of 1968. .......................................................................................................................................................83 Section II — Firearms classified as curios or relics, still subject to the provisions of 18 U.S.C. -

LIBYA CONFLICT: SITUATION UPDATE May 2011

U.S. & Coalition Operations and Statements LIBYA CONFLICT: SITUATION UPDATE May 2011 MAY 27: Russia has shifted its position on Libya and now believes Qaddafi has lost the legitimacy to rule and should leave power. Russia has offered to mediate a ceasefire and negotiate his departure with senior members of Qaddafi’s inner-circle. The pivot in Russian policy comes after a meeting between President Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev Russian at the G8 summit in France. Prime Minister Vladimir Putin has been highly critical of the NATO bombing campaign and Medvedev’s earlier decision to not veto the U.N Security Council resolution authorizing the allied action. After Medvedev’s decision, Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said, “Colonel Gaddafi has deprived himself of legitimacy with his actions, we should help him leave.” New( York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Reuters, Reuters, Al-Jazeera) MAY 27: The G8 nations announced in their joint summit communiqué that Qaddafi had no future role in a democratic Libya and the group demanded the regime’s forces cease their attacks against civilians. The communiqué stated that those behind the killing of civilians would be investigated and punished. (Reuters) MAY 27: British officials cleared the use of attack helicopters in Libya on Thursday. British officials have said that the addition of British Apaches and French Tiger helicopters into the battle will allow for low-level, precision attacks on urban targets, including Libyan officials. In a shift, the helicopters will be operated under NATO command instead of national command, NATO officials said that four Apache attack helicopters were available from the assault ship HMS Ocean as well as four Tigers aboard the French helicopter carrier Tonnerre. -

Readers Select Nominees for 2006 Jazzweek Awards

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • May 22, 2006 Volume 2, Number 26 • $7.95 In This Issue: 2006 JazzWeek Awards Nominees Announced . 4 John Hicks Dies at 64 . 5 Festival Update: JVC-Newport Jazz Radio Q&A: and Detroit . 7 WNCU’S Music and Industry News BH HUDSON In Brief . 8 page 11 Reviews and Picks . 15 Jazz Radio . 18 Smooth Jazz Radio. 25 Radio Panels. 24, 29 News. 4 Charts: #1 Jazz Album – Karrin Allyson #1 Smooth Album – Paul Brown #1 Smooth Single – Paul Brown JazzWeek This Week EDITOR/PUBLISHER Ed Trefzger eaders have spoken ... this year’s nominees for the fourth MUSIC EDITOR annual JazzWeek Awards have been tabulated. Check out Tad Hendrickson Rthe list of nominees on page 4 and be sure to send in your CONTRIBUTING EDITORS ballot. The ballot is found on page 31 (or may be downloaded from Keith Zimmerman http://www.jazzweek.com/2006ballot.pdf). Deadline for ballots Kent Zimmerman is May 26 at noon ET. Congratulations to all nominees. CONTRIBUTING WRITER/ PHOTOGRAPHER Tom Mallison ••• PHOTOGRAPHY Barry Solof With all of the doom and gloom around jazz radio in the past few weeks, it’s nice to hear about a success story: that’s at WNCU. Founding Publisher: Tony Gasparre Music director BH Hudson chats with music editor Tad Hen- drickson about what has led to programming – and, because of ADVERTISING: Devon Murphy Call (866) 453-6401 ext. 3 or that, fundraising – success at that North Carolina station. email: [email protected] ••• SUBSCRIPTIONS: Free to qualified applicants Premium subscription: $149.00 per year, This year’s JazzWeek Summit will run from Thursday, June 15 w/ Industry Access: $249.00 per year To subscribe using Visa/MC/Discover/ through Saturday, June 17, coinciding with the final three days AMEX/PayPal go to: of the Rochester International Jazz Festival.