THE SHIFTING of REGULATION in a DEREGULATED Environmenti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

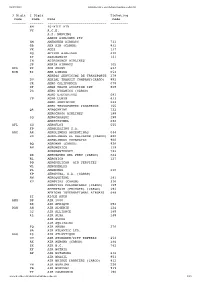

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

7 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report

2012_CAFR_Cover_fin.pdf 1 4/30/13 10:24 AM Washington Dulles International Airport Late 1970s 2012CAFR Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2012 Washington Dulles International Airport 7 50th Anniversary Geographically located in Virginia–serving the metropolitan Washington, D.C. area METROPOLITAN WASHINGTON AIRPORTS AUTHORITY COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2012 BOARD OF DIRECTORS As of December 31, 2012 Chairman Vice Chairman Michael A. Curto The Honorable Thomas M. Davis III Earl Adams, Jr. Richard S. Carter Lynn Chapman Frank M. Conner III The Honorable H.R. Crawford Anthony H. Griffin Shirley Robinson Hall Barbara Lang The Honorable Elaine McConnell Caren Merrick Warner H. Session Todd A. Stottlemyer EXECUTIVE STAFF John E. Potter President and Chief Executive Officer Margaret E. McKeough Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer Quince T. Brinkley, Jr. Vice President and Secretary Andrew T. Rountree, CPA Vice President for Finance and Chief Financial Officer Mark D. Adams Deputy Chief Financial Officer Valerie A. Holt, CPA Vice President for Audit Prepared by the Office of Finance Geographically located in Virginia – serving the metropolitan Washington, D.C. area INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority METROPOLITAN WASHINGTON AIRPORTS AUTHORITY Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2012 Table of Contents INTRODUCTORY SECTION Transmittal -

Bankruptcy Tilts Playing Field Frank Boroch, CFA 212 272-6335 [email protected]

Equity Research Airlines / Rated: Market Underweight September 15, 2005 Research Analyst(s): David Strine 212 272-7869 [email protected] Bankruptcy tilts playing field Frank Boroch, CFA 212 272-6335 [email protected] Key Points *** TWIN BANKRUPTCY FILINGS TILT PLAYING FIELD. NWAC and DAL filed for Chapter 11 protection yesterday, becoming the 20 and 21st airlines to do so since 2000. Now with 47% of industry capacity in bankruptcy, the playing field looks set to become even more lopsided pressuring non-bankrupt legacies to lower costs further and low cost carriers to reassess their shrinking CASM advantage. *** CAPACITY PULLBACK. Over the past 20 years, bankrupt carriers decreased capacity by 5-10% on avg in the year following their filing. If we assume DAL and NWAC shrink by 7.5% (the midpoint) in '06, our domestic industry ASM forecast goes from +2% y/y to flat, which could potentially be favorable for airline pricing (yields). *** NWAC AND DAL INTIMATE CAPACITY RESTRAINT. After their filing yesterday, NWAC's CEO indicated 4Q:05 capacity could decline 5-6% y/y, while Delta announced plans to accelerate its fleet simplification plan, removing four aircraft types by the end of 2006. *** BIGGEST BENEFICIARIES LIKELY TO BE LOW COST CARRIERS. NWAC and DAL account for roughly 26% of domestic capacity, which, if trimmed by 7.5% equates to a 2% pt reduction in industry capacity. We believe LCC-heavy routes are likely to see a disproportionate benefit from potential reductions at DAL and NWAC, with AAI, AWA, and JBLU in particular having an easier path for growth. -

2015 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report

METROPOLITAN KNOXVILLE AIRPORT AUTHORITY 2015 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report A component unit of the City of Knoxville, Tennessee For the fiscal years ended June 30, 2015 and 2014 PREPARED BY: Accounting and Finance Department of Metropolitan Knoxville Airport Authority www.flyknoxville.com This page intentionally left blank Metropolitan Knoxville Airport Authority Knoxville, Tennessee A COMPONENT UNIT OF THE CITY OF KNOXVILLE Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For the Fiscal Years Ended June 30, 2015 and 2014 PREPARED BY THE ACCOUNTING AND FINANCE DEPARTMENT This page intentionally left blank Introductory Section This section contains the following subsections: Table of Contents Metropolitan Knoxville Airport Authority Officials Letter of Transmittal and Exhibits Organizational Chart 1 This page intentionally left blank 2 METROPOLITAN KNOXVILLE AIRPORT AUTHORITY TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory section Metropolitan Knoxville Airport Authority Officials 5 Letter of transmittal and exhibits 7 Organizational chart 16 Financial section Report of Independent Auditors 19 Management’s discussion and analysis 22 Financial statements: Statements of net position 30 Statements of revenues, expenses and changes in net position 32 Statements of cash flows 33 Notes to financial statements 35 Statistical section (unaudited) Schedule 1: Operating revenues and expenses—last ten years 50 Schedule 2: Debt service coverage—last ten years 52 Schedule 3: Ratios of debt service and outstanding debt—last ten years 54 Schedule 4: McGhee Tyson Airport -

ALBANY COUNTY AIRPORT AUTHORITY Comprehensive Annual Financial Report

ALBANY COUNTY AIRPORT AUTHORITY Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For the Years Ended December 31, 2019 and 2018 New York’s Tech Valley Airport A component unit of the County of Albany, located in the Town of Colonie, New York flyalbany.com Albany County Airport Authority As of December 31, 2019 Authority Board Members Rev. Kenneth J. Doyle Anthony Gorman Chair Vice-Chair Term Expires: December 31, 2019 Term Expires: December 31, 2020 Samuel A. Fresina Lyon M. Greenberg, MD Steven H. Heider Member Treasurer Term Expires: December 31, 2020 Member Term Expires: December 31, 2021 Term Expires: December 31, 2021 Kevin R. Hicks, Sr. Sari O’Connor Member Member Term Expires: December 31, 2020 Term Expires: December 31, 2020 Authority Management Philip F. Calderone, Esq. Michael F. Zonsius, CPA Peter F. Stuto, Esq. ALBANY COUNTY AIRPORT AUTHORITY COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT Years Ended December 31, 2019 and 2018 Prepared by the Finance Department Michael F. Zonsius, CPA Chief Financial Officer Margaret Herrmann Chief Accountant A Component Unit of the County of Albany Town of Colonie, New York www.albanyairport.com CUSIP #012123XXX Additional information relating to the Airport Authority is available at the Airport’s website: www.flyalbany.com If you would like any further information, contact the Chief Financial Officer at (518) 242-2204 or at Albany County Airport Authority, 737 Albany Shaker Rd, Administration Building Room 204, Albany, NY 12211 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE(S) I. INTRODUCTORY SECTION Albany County Airport Authority: Members and Principal Officers ................................................ Inside Front Cover Chairman’s Message ................................................................................................... 1 Letter of Transmittal ............................................................................................... 2-11 Organizational Chart ................................................................................................ -

1 United States of America

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BEFORE THE NATIONAL MEDIATION BOARD ) ) In re ABX Air, Inc. and ) Air Transport Int’l, Inc. ) NMB Case No. CR-7157 ) ) SUPPLEMENTAL POSITION STATEMENT OF INTERNATIONAL BROTHERHOOD OF TEAMSTERS This case presents the National Mediation Board with a unique corporate structure, one not found in prior air carrier single transportation system cases, in which a parent holding company has exercised its complete control over the corporate structure and operations of its affiliates to break out the core functions otherwise found in a single air carrier into a network of integrated subsidiaries. As will be discussed, ATSG has morphed into a highly integrated enterprise consisting of several subsidiaries and divisions working together to perform specific functions that previously had been performed directly by ABX Air and ATI. In this regard, ATSG removed from ABX Air core functions of fleet and fleet management, maintenance, marketing, flight following and logistics, and restructured those functions into other wholly-owned subsidiaries. Similarly, ATSG merged two of its air carrier subsidiaries, Air Transport International and Capital Cargo, Inc.., into a single air carrier -- the surviving ATI. ABX and ATI operate together with the other ATSG subsidiaries to service ATSG’s principal customers DHL Worldwide and Amazon. The subsidiaries act in an integrated fashion to perform the air services negotiated and structured by ATSG. ABX and ATI exchange aircraft and provide subservice to one another, for example, so that neither is required to engage a 1 third party for those services. Neither maintains a fleet. ATSG aircraft leasing subsidiary CAM owns their aircraft. -

Nextpage Livepublish

Appendix Appendix A: Maintenance-Related Accidents as reported by the National Transportation Safety Board DATE AIRLINE LOCATION 7/30/71 Pan American San Francisco, CA 2/8/76 Mercer Airlines, Inc. Van Nuys, CA 5/25/79 American Chicago, IL 9/20/81 World Airways, Inc. Flight 32 Over North Atlantic Ocean 9/22/81 Eastern (935) Colts Neck, NJ 9/22/81 Air Florida Airlines, Inc. Miami Int'l Airport, Miami, FL 1/13/82 Air Florida, Inc. Near Washington Nat'l Airport Washington, DC 3/24/82 TigerAir, Inc. Marana, AZ 2/15/83 Eastern Air Lines Flight 194 Miami, FL 5/5/83 Eastern Miami Int'l 6/2/83 Air Canada Flight 797 Greater Cincinnati Int'l Airport Covington, KY 11/11/83 Eastern Airlines Flight 836 Miami Int'l Airport 2/28/84 Scandinavian Airlines Systems Flight 901 JFK Int'l Airport Jamaica, New York 2/19/85 China Airlines 300 Nautical miles northwest of San Francisco, CA 5/28/85 American Airlines Jamaica, New York 9/6/85 Midwest Express General Billy Mitchell Field Milwaukee, WI 4/8/86 United Airlines Flight 732 Chicago, IL 5/25/86 Continental Airlines Flight 199 Corpus Christi, Texas 4/28/88 Aloha Airlines Maui, Hawaii 8/31/88 Delta Air Lines, Inc. Dallas Ft.-Worth, Int'l Airport Dallas 2/24/89 United Airlines Flight 811 Honolulu, Hawaii 3/18/89 Evergreen Int'l Saginaw, Texas 7/19/89 United (232) Sioux Gateway 12/30/89 America West Airlines Flight 450 Tucson, Arizona 5/3/91 Ryan Int'l Airlines, Inc. -

(Expressjet Airlines, Inc.) 브리트 에어웨이 - 콘티넨탈 익스프레스 / 에어 마이크 익스프레스

Britt Airways, D/B/A Continental Express / Air Mike Express (ExpressJet Airlines, Inc.) 브리트 에어웨이 - 콘티넨탈 익스프레스 / 에어 마이크 익스프레스 국 적 : United States / 미국 코 드 : XE / BTA 콜사인 : JET LINK 기준일: 2008.12.31 ◎ 개요 ▶ 주소 1600 Smith Street, HQSCE, Houston, Texas 77002, United States ▶ 전화 : (+1 713) 324 26 39 ▶ 팩스 : (+1 713) 324 44 20 ▶ 홈페이지 : http://www.expressjet.com ◎ 역사 ▶ 이 항공사의 변경전 이름은 피플익스프레스(People Express)로서 1987년 콘티넨탈항공에 인수되어 콘티넨탈항공이 100% 지분을 소유하는 자회사가 되었다. 2002년 4월 17일, ExpressJet Holdings는 보통주 10만주와 더불어 콘티넨탈항공이 소유하였던 20만 주를 더하여 주당 16달러에 IPO 공모를 하였다. 인수인에게 옵션으로써 추가의 4백5십만주가 상장되었 다. 2003년 7월, ExpressJet은 추가로 45%로 소유권을 줄이면서 콘티넨탈항공으로부터 지분을 매수하기위 해서 1억3천7백2십만달러의 전환사채를 발행하여 수입금을 사용하였다. 콘티넨탈은 자체의 연금계획에 추가로 1억만달러를 기부하였고 비핵심자산 처분의 일환으로 점차적으로 보유지분(0 으로)을 감소하였 다. 이 항공사는 2010년 12월 31일까지유효한 구매계약서(capacity)를 통해서 휴스턴, 뉴왁 및 클리브랜드 의 허브로부터 콘티넨탈의 모든 지역제트기 서비스를 제공하고있다. (2006년 12월 31일까지 독점계약) 그리고 세계에서 가장 큰 지역항공사중의 하나가 되었다. 2006년 12월과 2007년 6월사이에 69대의 항공기는 구매계약서에서 삭제될 것이나 익스프레스젯 (ExpressJet)에 의해서 운항이 계속될 것이다. ◎ 시뮬레이터 수량 시뮬레이터 제조업체 컴퓨터 비주얼 레벨 1 ERJ-135 CAE IBM 6000 ESIG 3350 FAA Level D 2 ERJ-145 CAE IBM 6000 MAXVUE + FAA Level D ◎ 제휴현황 제휴파트너 동맹 유효일자 비고 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES, INC 2001-04월 capacity purchase agreement ◎ 재무현황 (Currency: US $ Million) 수입 회계연도종료일 2005-12-31 2004-12-31 2003-12-31 정기여객수입 부정기여객수입 화물및우편수입 기타 총운영수입 1,563 1,508 1,311 손익계산서 운영수입(손실) 156 205 182 순수익 +/- -2 -7 -7 기타수입/(지출) +/- 세전수익/(손실) 154 198 175 세금 +/- -56 -75 -67 순수익/(손실) 98 123 108 대차대조표 고정자산 240 262 247 투자 17 기타자산 23 28 29 순자산(부채) 130 47 15 총자산(당좌부채) 410 337 291 장기부채 151 175 284 장기리스 1 2 -

3 Digit 2 Digit Ticketing Code Code Name Code ------6M 40-MILE AIR VY A.C.E

06/07/2021 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt 3 Digit 2 Digit Ticketing Code Code Name Code ------- ------- ------------------------------ --------- 6M 40-MILE AIR VY A.C.E. A.S. NORVING AARON AIRLINES PTY SM ABERDEEN AIRWAYS 731 GB ABX AIR (CARGO) 832 VX ACES 137 XQ ACTION AIRLINES 410 ZY ADALBANAIR 121 IN ADIRONDACK AIRLINES JP ADRIA AIRWAYS 165 REA RE AER ARANN 684 EIN EI AER LINGUS 053 AEREOS SERVICIOS DE TRANSPORTE 278 DU AERIAL TRANSIT COMPANY(CARGO) 892 JR AERO CALIFORNIA 078 DF AERO COACH AVIATION INT 868 2G AERO DYNAMICS (CARGO) AERO EJECUTIVOS 681 YP AERO LLOYD 633 AERO SERVICIOS 243 AERO TRANSPORTES PANAMENOS 155 QA AEROCARIBE 723 AEROCHAGO AIRLINES 198 3Q AEROCHASQUI 298 AEROCOZUMEL 686 AFL SU AEROFLOT 555 FP AEROLEASING S.A. ARG AR AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 044 VG AEROLINEAS EL SALVADOR (CARGO) 680 AEROLINEAS URUGUAYAS 966 BQ AEROMAR (CARGO) 926 AM AEROMEXICO 139 AEROMONTERREY 722 XX AERONAVES DEL PERU (CARGO) 624 RL AERONICA 127 PO AEROPELICAN AIR SERVICES WL AEROPERLAS PL AEROPERU 210 6P AEROPUMA, S.A. (CARGO) AW AEROQUETZAL 291 XU AEROVIAS (CARGO) 316 AEROVIAS COLOMBIANAS (CARGO) 158 AFFRETAIR (PRIVATE) (CARGO) 292 AFRICAN INTERNATIONAL AIRWAYS 648 ZI AIGLE AZUR AMM DP AIR 2000 RK AIR AFRIQUE 092 DAH AH AIR ALGERIE 124 3J AIR ALLIANCE 188 4L AIR ALMA 248 AIR ALPHA AIR AQUITAINE FQ AIR ARUBA 276 9A AIR ATLANTIC LTD. AAG ES AIR ATLANTIQUE OU AIR ATONABEE/CITY EXPRESS 253 AX AIR AURORA (CARGO) 386 ZX AIR B.C. 742 KF AIR BOTNIA BP AIR BOTSWANA 636 AIR BRASIL 853 AIR BRIDGE CARRIERS (CARGO) 912 VH AIR BURKINA 226 PB AIR BURUNDI 919 TY AIR CALEDONIE 190 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt 1/15 06/07/2021 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt SB AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 063 ACA AC AIR CANADA 014 XC AIR CARIBBEAN 918 SF AIR CHARTER AIR CHARTER (CHARTER) AIR CHARTER SYSTEMS 272 CCA CA AIR CHINA 999 CE AIR CITY S.A.