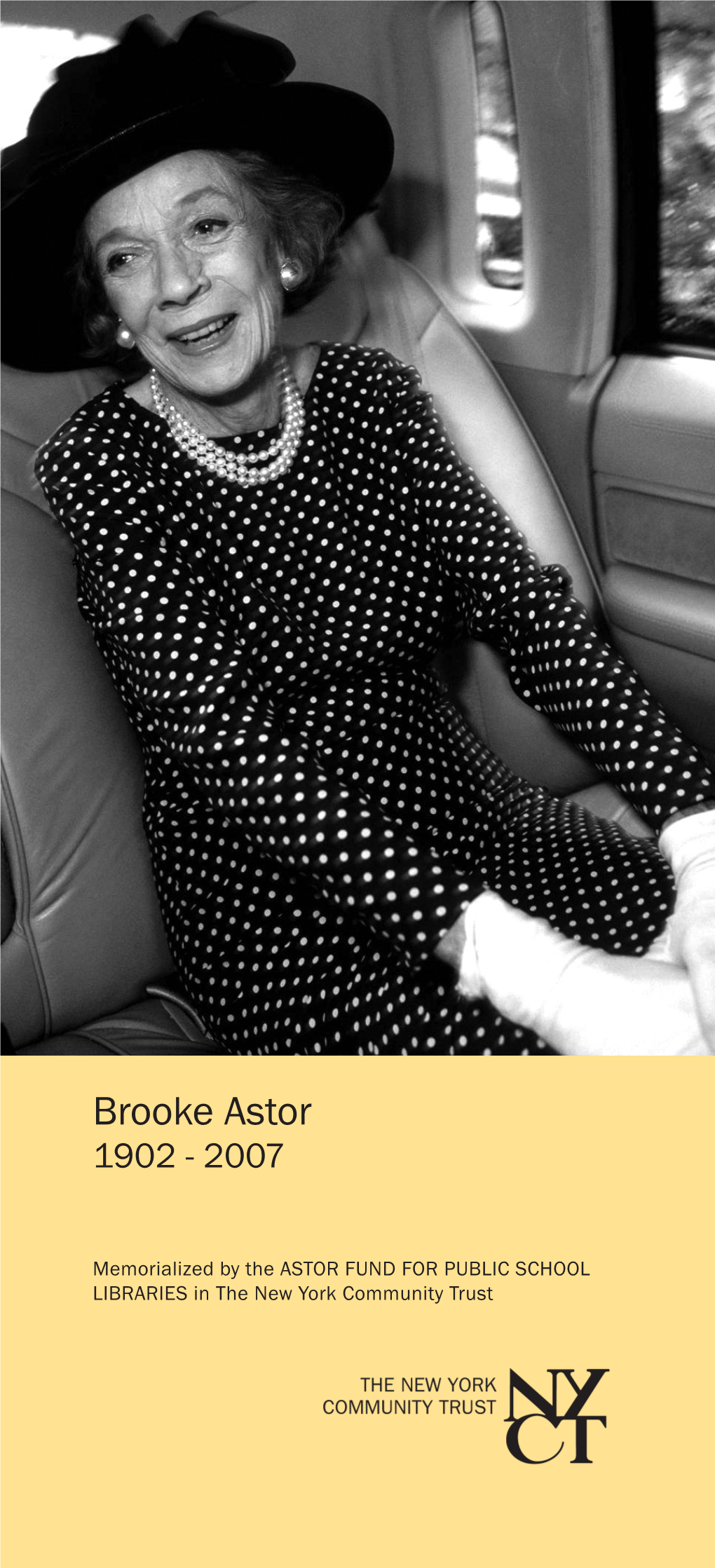

Brooke Astor 1902 - 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Service of Others: from Rose Hill to Lincoln Center

Fordham Law Review Volume 82 Issue 4 Article 1 2014 In the Service of Others: From Rose Hill to Lincoln Center Constantine N. Katsoris Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Constantine N. Katsoris, In the Service of Others: From Rose Hill to Lincoln Center, 82 Fordham L. Rev. 1533 (2014). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol82/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEDICATION IN THE SERVICE OF OTHERS: FROM ROSE HILL TO LINCOLN CENTER Constantine N. Katsoris* At the start of the 2014 to 2015 academic year, Fordham University School of Law will begin classes at a brand new, state-of-the-art building located adjacent to the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. This new building will be the eighth location for Fordham Law School in New York City. From its start at Rose Hill in the Bronx, New York, to its various locations in downtown Manhattan, and finally, to its two locations at Lincoln Center, the law school’s education and values have remained constant: legal excellence through public service. This Article examines the law school’s rich history in public service through the lives and work of its storied deans, demonstrating how each has lived up to the law school’s motto In the service of others and concludes with a look into Fordham Law School’s future. -

"Redeveloping" Corporate Governance Structures: Non-For-Profit Governance During Major Capital Projects, a Case Study at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts

Fordham Law Review Volume 76 Issue 2 Article 14 2007 "Redeveloping" Corporate Governance Structures: Non-For-Profit Governance During Major Capital Projects, A Case Study at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts Lesley Friedman Rosenthal Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lesley Friedman Rosenthal, "Redeveloping" Corporate Governance Structures: Non-For-Profit Governance During Major Capital Projects, A Case Study at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, 76 Fordham L. Rev. 929 (2007). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol76/iss2/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Redeveloping" Corporate Governance Structures: Non-For-Profit Governance During Major Capital Projects, A Case Study at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts Cover Page Footnote J.D., Harvard Law School, 1989; A.B., Harvard College, 1986; Vice President, General Counsel, and Secretary, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, Inc. Ms. Rosenthal plays a lead role in fashioning the legal context for the ongoing redevelopment projects on the Lincoln Center campus. She is also part of the management committee team that is modernizing how Lincoln Center manages retail sales, restaurant and catering transactions, and parking. In her role as secretary, Ms. Rosenthal regularly interacts with the board of directors, drafting corporate resolutions and advising on corporate governance matters. -

A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: a Century of Service

Fordham Law Review Volume 75 Issue 5 Article 1 2007 A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: A Century of Service Constantine N. Katsoris Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Constantine N. Katsoris, A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: A Century of Service, 75 Fordham L. Rev. 2303 (2007). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol75/iss5/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: A Century of Service Cover Page Footnote * This article is dedicated to Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, the first woman appointed ot the U.S. Supreme Court. Although she is not a graduate of our school, she received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Fordham University in 1984 at the dedication ceremony celebrating the expansion of the Law School at Lincoln Center. Besides being a role model both on and off the bench, she has graciously participated and contributed to Fordham Law School in so many ways over the past three decades, including being the principal speaker at both the dedication of our new building in 1984, and again at our Millennium Celebration at Lincoln Center as we ushered in the twenty-first century, teaching a course in International Law and Relations as part of our summer program in Ireland, and participating in each of our annual alumni Supreme Court Admission Ceremonies since they began in 1986. -

Society of Fellows News American Academy in Rome

SOCIETY OF FELLOWS NEWS AMERICAN ACADEMY IN ROME LETTERS FALL 2003 From the Editors Stefanie Walker FH’01, Catherine Seavitt FA’98 What’s in a letter? is exemplified by the collaborative Society of Fellows NEWS work of two of the 2002-03 Fellows, The theme of this issue of the SOF FALL 2003 Peter Orner FW’03 NEWS explores that question, and we writer and visual Published by the Society of Fellows of are pleased at the diversity of artist Arthur Simms FV’03. It is truly in The American Academy in Rome responses. Paul Davis FD’98, fascinat- this fluid back-and-forth exchange 7 East 60 Street ed by the transformation of the cor- that we feel the most hope for corre- New York, NY 10022-1001 USA rugated metal walls around Roman spondence. There is nothing stranger tel 212 751 7200 www.sof-aarome.org Co-Editors: Stefanie Walker FH’01 construction sites into public bulletin than reading just one half of a dia- Catherine Seavitt FA’98 boards, provides us with our fantastic logue of letters, as we are so often Contributors: Joanne Spurza FC’89 cover. Other contributions center on forced to do. It is then left to our Brian Curran FH’94 the long history of letter writing, as imagination to fill in the missing let- SOF Liason: Elsa Dessberg studied by historian Emil J. Polak ters of the other correspondent. And FR’63 in his delightful interview with there is certainly the poignancy of Editor Stefanie Walker FH’01. The letters left unanswered - or letters Contents graphics of the Imperial Roman that one knows will not be answered, SOF President’s Message 3 ABC’s are studied by Sumner Stone such as those addressed to Defense 7 East 60 Street 4 Via Angelo Masina 5 5 VA’98 in his detailed analysis of the Secretaries or dead Roman senators. -

Careers at RFCUNY Job Openings Job Title: Literacy Specialist PVN ID: HC-1508-000667 Category: Instruction and Social Service Lo

Careers at RFCUNY Job Openings Job Title: Literacy Specialist PVN ID: HC-1508-000667 Category: Instruction and Social Service Location: HUNTER COLLEGE Department: School of Education Status: Part Time Hourly Rate: $50.00-$60.00 General Description: Brooke Astor was an American philanthropist, socialite, writer, and president of the Vincent Astor Foundation, established by her husband, Vincent Astor. She died August 2007, at the age of 105, the New York Times called her the City's “First Lady of Philanthropy.” Mrs. Astor's dedication to philanthropy and the City of New York continues. As part of the settlement for her estate, the Brooke Astor Fund for New York City Education (“Astor Fund”) was created and The New York Community Trust was selected to administer it. The New York Community Trust (NYCT) awarded a grant to Hunter College School of Education for the READ East Harlem project to improve the literacy abilities of early childhood students in New York City public schools in East Harlem. Hunter College School of Education is seeking a literacy specialist to support the READ East Harlem project. Job Description: • Assigned to two to four schools in East Harlem • Provide monthly professional development in literacy development and instruction to classroom teachers and Hunter College teacher candidates • Provide on-site support to classroom teachers participating in the project (e.g., classroom observations, modeling). • Collect data and participate in monthly project meetings. Other Duties: Qualifications: Qualifications: • Masters in Literacy (or related field) • 3 to 5 years of teaching experience working the children in grades Kindergarten to 2nd • Knowledge of bilingual and/or special education, a plus • Prior mentoring experience, a plus. -

The National Arts Awards Chair

1 Edye and Eli Broad salute Americans for the Arts and 2 tonight’s honorees for their commitment ensuring broad access to the arts 2014 Americans for the Arts National Arts Awards Monday, October 20, 2014 Welcome from Robert L. Lynch Performance by YoungArts Alumni President and CEO of Americans for the Arts Outstanding Contributions to the Arts Award Legacy Award American Legion Auxiliary Madeleine H. Berman Presented by Nolen V. Bivens, Presented by Anne Parsons Brigadier General, U.S. Army, (Ret) Accepted by Janet Jefford Lifetime Achievement Award Richard Serra Eli and Edythe Broad Award for 3 Presented by Jennifer Russell Philanthropy in the Arts Vicki and Roger Sant Arts Education Award Presented by The Honorable Christopher J. Dodd P.S. ARTS Presented by Ben Stiller Bell Family Foundation Young Artist Award Accepted by Joshua B. Tanzer David Hallberg Presented by RoseLee Goldberg Dinner Closing Remarks Robert L. Lynch introduction of Maria Bell Abel Lopez, Chair, Americans for the Arts Vice Chairman, Americans for the Arts Board of Board of Directors Directors and Chair, National Arts Awards and Robert L. Lynch Greetings from the Board Chair and President It is our pleasure to welcome you to our annual Americans for the Arts National Arts Awards. Tonight we again celebrate a select group of cultural leaders— groundbreaking artists, visionary philanthropists, and two outstanding nonprofit organizations—who help ensure that every American has access to the transformative power of the arts. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all of our honorees. In this time of increasing challenges to our nation’s security and the sacrifices made by our servicemen and women and their families, we are especially pleased to recognize the American Legion Auxiliary, one of our many partners in the work we do with the military and veterans on the role of the arts & healing. -

NEA Chronology Final

THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS 1965 2000 A BRIEF CHRONOLOGY OF FEDERAL SUPPORT FOR THE ARTS President Johnson signs the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act, establishing the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, on September 29, 1965. Foreword he National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act The thirty-five year public investment in the arts has paid tremen Twas passed by Congress and signed into law by President dous dividends. Since 1965, the Endowment has awarded more Johnson in 1965. It states, “While no government can call a great than 111,000 grants to arts organizations and artists in all 50 states artist or scholar into existence, it is necessary and appropriate for and the six U.S. jurisdictions. The number of state and jurisdic the Federal Government to help create and sustain not only a tional arts agencies has grown from 5 to 56. Local arts agencies climate encouraging freedom of thought, imagination, and now number over 4,000 – up from 400. Nonprofit theaters have inquiry, but also the material conditions facilitating the release of grown from 56 to 340, symphony orchestras have nearly doubled this creative talent.” On September 29 of that year, the National in number from 980 to 1,800, opera companies have multiplied Endowment for the Arts – a new public agency dedicated to from 27 to 113, and now there are 18 times as many dance com strengthening the artistic life of this country – was created. panies as there were in 1965. -

Carnegie Hall Was Born of the Vision of a Great Philanthropist, and to This Day the Generosity of Our Donors Is the Bedrock of Its Continued Donors Success

Carnegie Hall was born of the vision of a great philanthropist, and to this day the generosity of our donors is the bedrock of its continued Donors success. We thank our generous Trustees and the nearly 11,000 donors who contributed more than $27 million for the Annual Fund during the 2016–2017 season, enabling Carnegie Hall to continue the expansion of its artistic and education programs and strengthen its capacity to serve broad new audiences for years to come. Lee Chris Notables post-concert event 54 55 Platinum Circle ($50,000 to $99,999) E. H. A. Foundation Enoch Foundation Estate of Roger Abelson The Jack Benny Family Foundation Estate of Philip Chaves Ann and Gordon Getty Foundation Daniel Clay Houghton Blanche and Irving Laurie Foundation Mr. and Mrs. Terry J. Lundgren Rockefeller Brothers Fund Mr. Jay B. Rosenberg Suki Sandler Mrs. Henry T. Segerstrom Shubert Foundation Mr. and Mrs. A. J. C. Smith Anonymous (2) Hope and Robert F. Smith, Emily and Len Blavatnik, Sanford I. Weill, Mercedes T. Bass, and Clive Gillinson Beatrice Santo Domingo Golden Circle ($25,000 to $49,999) Mr. and Mrs. Frederick C. Benenson Donors Bialkin Family Foundation Ronald E. Blaylock The Edwin Caplin Foundation Platinum Circle Leslie and Tom Maheras The Ralph M. Cestone Foundation ($100,000 or more) Andrew J. Martin-Weber Mrs. Judith Chasanof Leni and Peter May Mr. and Mrs. Bruce Crawford Linda and Earle S. Altman The Harold W. McGraw, Jr. Family Foundation Mr. and Mrs. Richard A. Debs Estate of Brooke Astor The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation Brooke Astor Fund for New York City Education in The New York Community Trust Mr. -

![Papers of W. Averell Harriman [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3626/papers-of-w-averell-harriman-finding-aid-library-of-congress-2863626.webp)

Papers of W. Averell Harriman [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

W. Averell Harriman A Register of His Papers in the Library of Congress Prepared by Allan Teichroew with the assistance of Haley Barnett, Connie L. Cartledge, Paul Colton, Marie Friendly, Patrick Holyfield, Allyson H. Jackson, Patrick Kerwin, Mary A. Lacy, Sherralyn McCoy, John R. Monagle, Susie H. Moody, Sheri Shepherd, and Thelma Queen Revised by Connie L. Cartledge with the assistance of Karen Stuart Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2001 Contact information: http://lcweb.loc.gov/rr/mss/address.html Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2003 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms003012 Latest revision: 2008 July Collection Summary Title: Papers of W. Averell Harriman Span Dates: 1869-1988 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1895-1986) ID No.: MSS61911 Creator: Harriman, W. Averell (William Averell), 1891-1986 Extent: 344,250 items; 1,108 containers plus 11 classified; 526.3 linear feet; 54 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Diplomat, entrepreneur, philanthropist, and politician. Correspondence, memoranda, family papers, business records, diplomatic accounts, speeches, statements and writings, photographs, and other papers documenting Harriman's career in business, finance, politics, and public service, particularly during the Franklin Roosevelt, Truman, Kennedy, Johnson, and Carter presidential administrations. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. Personal Names Abel, Elie. Acheson, Dean, 1893-1971. -

George Trescher Records Related to the Metropolitan Museum of Art Centennial, 1949, 1960-1971 (Bulk 1967-1970)

George Trescher records related to The Metropolitan Museum of Art Centennial, 1949, 1960-1971 (bulk 1967-1970) Finding aid prepared by Celia Hartmann and Arielle Dorlester Processing of this collection was funded by a generous grant from the Leon Levy Foundation This finding aid was generated using Archivists' Toolkit on February 02, 2017 The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives 1000 Fifth Avenue New York, NY, 10028-0198 212-570-3937 [email protected] George Trescher records related to The Metropolitan Museum of Art Centennial, 1949, 1960-1971 (bulk ... Table of Contents Summary Information .......................................................................................................3 Biographical note.................................................................................................................4 Historical note..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note.....................................................................................................6 Arrangement note................................................................................................................ 7 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 7 Related Materials .............................................................................................................. 7 Controlled Access Headings.............................................................................................. -

Lead. Engage. Inspire. Amplify

APPRECIATIONAPRIL IS JAZZ FREE POSTER INSIDE! MONTH teachingmusicmusicAPRIL 2018 VOLUME 25, NUMBER 4 Teaching the Music of the HARLEM RENAISSANCE ACCORDIONS in the Classroom NAfME 2018 IN DALLAS AMPLIFY: LEAD. ENGAGE. INSPIRE. JAZZ STRING Orchestras menc.org 1 You’re the Expert, Teach Your Way C M Tools for Every Style of Teaching Y CM MY Introducing Quaver’s Song-Based Lessons 38 new lessons using CY tools and techniques inspired by Kodály, Or, and Music Learning CMY Theory approaches to music education. K Try 8 new lessons FREE in your classroom for 30 days! Visit QuaverMusic.com/TM82017 today and download a bonus song or poster of your choice to keep! @QuaverMusic ©2017 QuaverMusic.com, LLC JAZZ POSTER FREE! April 2018 Volume 25, Number 4 PROMOTINGcontents THE U NDERSTANDING AND MAKING OF MUSIC B Y ALL Music students learn cooperation, discipline, and teamwork. 36 MEET THE ANHE CONDUCTORS! The directors of the five 2018 All-National Honor Ensembles give their perspectives on what makes successful musicians and effective conductors. FEATURES 18 ACCORDION 22 TEACHERS’ 28 A MGNUM OPUS! 32 FINDING A WAY AT ADVOCACY: VOICES For NAfME’s 2018 FRANKLIN HIGH BRINGING THE RESULTS AND National Conference, Jacqueline Hairston ACCORDION RECOMMENDATIONS Opus Leaders are took a big chance when INTO THE GENERAL What is the status of working to create and she revived the Marching MUSIC CLASSROOM music education in engage music educators Yellow Jackets of The accordion can the U.S. right now, and in five key areas. Meet Franklin High School make a strong—and where are we headed? the Leaders and learn in Stockton, California, festive—addition to The results of a recent about each Opus. -

Read Pg. 22 of Our Conservation News

Conservation News Protecting Open Space on Long Island’s North Shore NORTH SHORE LAND ALLIANCE Board of Trustees Volume 10, Issue 19 Carter Bales, Chair Spring /Summer 2014 John Bralower, Vice-Chair Hal Davidson, Vice-Chair Hoyle Jones, Vice-Chair Luis Rinaldini, Vice-Chair Rosemary Bourne, Treasurer Hollis Russell, Secretary Peter Bartley Matthew Bruderman Frank Castagna Gilbert Chapman Leland Deane Augusta Donohue Nancy Douzinas George Eberle Max Geddes Lynn Gray David Holmes Nancy Kelley Warren Kraft Tom Lieber Bridget Macaskill Patrick Mackay Tom McGrath Clarence Michalis Jonathan Moore Peter Quick Patsy Randolph Julie Rinaldini The field at the top of the DeForest Williams property Larry Schmidlapp Ray Schuville Frank Segarra DeForest Williams Challenge Grant Met - Hope Smith Zach Taylor Paula Weir $330,000 To Go Peri Wenz Tom Zoller We are very pleased to report that completion of the Campaign to Acquire the 32-Acre Trustee Emeritus Danny Davison DeForest Williams Property in Cold Spring Harbor is drawing near. Our community has done Advisory Board something quite wonderful here and we are so close to the finish line. Among government, Myron Blumenfeld Ann Cannell foundations and private individuals – WE HAVE RAISED $8,170,000 TOWARD THIS Judith Chapman Katusha Davison $8,500,000 PURCHASE! Mark Fasciano Louise Harrison Erik Kulleseid Most notably, on May 31st, we met the $500,000 dollar-for-dollar, matching grant Neal Lewis Robert Mackay opportunity extended to us in late February by an exceedingly helpful anonymous donor. Sarah Meyland Barry Osborn But, we are not there yet ... we still have $330,000 to go to complete the entire transaction! Peter Schiff John Turner Richard Weir As an added incentive to donors, the Land Alliance has developed a naming rights program Staff Lisa Ott, President/CEO which allows generous donors to endow the stewardship of a beautiful tree, install a native Julie Davidson, Senior pollinator garden, plant a small orchard of fruit trees or purchase a bench to honor a family Development Officer Directors: member or friend.