Medieval Institute Publications Board of Trustees of Western Michigan University Through Its Medieval Institute Publications Trustees of Princeton University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preliminary Investigation of the Iconography of the Woman with the Skull from the Puerta De Las Platerías of Santiago De Compostela

PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATION OF THE ICONOGRAPHY OF THE WOMAN WITH THE SKULL FROM THE PUERTA DE LAS PLATERÍAS OF SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA By KAREN FAYE WEBB A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2004 Copyright 2004 by Karen Faye Webb To Dan and Judy Webb ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to many individuals for their support and guidance in my physical and conceptual pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. I would most like to thank Dr. David Stanley who has been my constant supporter as my toughest critic and my most caring mentor. Dr. Carolyn Watson’s medieval art class at Furman University introduced me to the complex beauty of the south transept portal. My parents indulged my awe of this portal and physically and metaphorically climbed the steps leading to the Puerta de las Platerías with me to pay homage to the Woman with the Skull. Without them, this study would not have been possible. I would like to thank my reader, Dr. John Scott, for his insightful comments, and Jeremy Culler, Sarah Webb and Sandra Goodrich for their support, friendship, and unwavering faith in me. Finally, I would like to thank the Woman with the Skull, who brought me on this pilgrimage and has given me a new awareness about art and myself. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................. iv LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... -

Constructing the Cámara Santa: Architecture, History, and Authority in Medieval Oviedo

Constructing the Cámara Santa: Architecture, History, and Authority in Medieval Oviedo by Flora Thomas Ward A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto © Copyright by Flora Thomas Ward 2014 Constructing the Cámara Santa: Architecture, History, and Authority in Medieval Oviedo Flora Thomas Ward Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto 2014 Abstract My dissertation examines the Cámara Santa of the Cathedral of Oviedo as both a medieval and modern monument, shaped by twelfth-century bishops and twentieth-century restorers. I consider the space as a multi-media ensemble, containing manuscripts, metalwork, and sculpture, arguing that we must view it as a composite—if fragmented—whole. My analysis focuses on the twelfth century, a crucial period during which the structure, decoration, and contents of the Cámara Santa were reworked. A key figure in this story is Bishop Pelayo of Oviedo (d. 1153), who sought to enhance the antiquity and authority of the see of Oviedo by means of the cult of its most important reliquary: the Arca Santa. I argue that this reliquary shapes the form and function of the twelfth-century Cámara Santa, considering the use of the space in the context of liturgy and pilgrimage. Finally, I consider the sculpture that lines the walls of the space, arguing that it animates and embodies the relics contained within the Arca Santa, interacting with the pilgrims and canons who used the space. Thus, this sculpture represents the culmination of the long twelfth-century transformation of the Cámara Santa into a space of pilgrimage focused around the Arca Santa and the memory of the early medieval patrons of the Cathedral of Oviedo, a memory which abides to this day. -

THE CONTENTS of a CATALONIAN VILLA the Collection of Anton Casamor Wednesday 11 April 2018

THE CONTENTS OF A CATALONIAN VILLA The Collection of Anton Casamor Wednesday 11 April 2018 THE CONTENTS OF A CATALONIAN VILLA The Collection of Anton Casamor Wednesday 11 April 2018 at 2pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION OF Sunday 8 April +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Head of Sale LOTS IN THIS AUCTION 11am to 3pm +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax Charlie Thomas Monday 9 April To bid via the internet +44 (0) 20 7468 8358 PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE 9am to 4.30pm please visit bonhams.com [email protected] IS NO REFERENCE IN THIS Tuesday 10 April CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL 9am to 4.30pm TELEPHONE BIDDING Administrator CONDITION OF ANY LOT. Wednesday 11 April Telephone bidding on this sale Mackenzie Constantinou INTENDING BIDDERS MUST 9am to 11am will only be accepted on lots +44 (0) 20 7468 5895 SATISFY THEMSELVES AS TO with a lower estimate of £1,000 mackenzie.constantinou@bonhams. THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT SALE NUMBER or above. com AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 24740 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS Please note that bids should Representative, Barcelona CONTAINED AT THE END OF CATALOGUE be submitted no later than 4pm Teresa Ybarra THIS CATALOGUE. £20.00 on the day prior to the sale. +34 680 347 606 New bidders must also provide [email protected] As a courtesy to intending proof of identity when submitting bidders, Bonhams will provide bids. Failure to do this may result Press a written Indication of the in your bid not being processed. -

The Libro Verde: Blood Fictions from Early Modern Spain

INFORMATION TO USERS The negative microfilm of this dissertation was prepared and inspected by the school granting the degree. We are using this film without further inspection or change. If there are any questions about the content, please write directly to the school. The quality of this reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original material The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When it is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to indicate this. 3. Oversize materials (maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sec tioning the original, beginning at the upper left hand comer and continu ing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Dissertation Information Service A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 9731534 Copyright 1997 by Beusterien, John L. All rights reserved. UMI Microform 9731534 Copyright 1997, by UMI Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Titic 17, United States Code. UMI 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 Reproduced with permission -

IMA VOL4 Prelims.Indd

VIVIAN B. MANN Jewish Theological Seminary OBSERVATIONS ON THE BIBLICAL MINIATURES IN SPANISH HAGGADOT Abstract the seder itself. Illuminated borders and word pan- This essay discusses the last two centuries of medieval Spanish art, els completed the program of illumination. and demonstrates that cooperative relations existed between Christians In all, there remain some seven haggadot from and Jews who worked either independently or together to create art Spain produced from ca. 1300 to ca. 1360 in the both for the Church and the Jewish community. Artists of different Crown of Aragon and Castile in which biblical faiths worked together in ateliers such as that headed by Ferrer Bassa miniatures precede the text of the haggadah. In an (d. 1348), producing both retablos (altarpieces) as well as Latin additional example, the Barcelona Haggadah (British and Hebrew manuscripts. Library, Add. 14761), the biblical scenes serve as The work of such mixed ateliers is of great signicance when text illustrations.3 The number and contents of these considering the genesis ca. 1300 of illuminated with haggadot illustrations are not uniform. The Hispano-Moresque prefatory biblical cycles and genre scenes that were produced in Spain until ca. 1360. These service books for Passover have Haggadah (British Library, Or. 2737), the Rylands always been viewed as a unique phenomenon within the Jewish art (Rylands Library, JRL Heb. 6), and its related of Spain, their origins inexplicable. When the biblical scenes, brother manuscript (British Library, Or. 1404) however, are viewed in the context of contemporaneous Spanish art adhere most closely to the text of the haggadah for the Church, their sources become more transparent. -

Jews and Altarpieces in Medieval Spain

jews and altarpieces in medieval spain 76 JEWS AND 77 ALTARPIECES IN MEDIEVAL SPAIN — Vivian B. Mann INTRODUCTION t first glance, the title of this essay may seem to be an oxymoron, but the reali- ties of Jewish life under Christian rule in late medieval Spain were subtle and complicated, even allowing Jews a role in the production of church art. This essay focuses on art as a means of illuminating relationships between Chris- tians and Jews in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Historians continue to discuss whether the convivencia that characterized the earlier Islamic rule on the Iberian Peninsula continued after the Christian Reconquest, the massacres following the Black Death in 1348 and, especially, after the persecutions of 1391 that initiated a traumatic pe- riod lasting until 1416. One view is that the later centuries of Jewish life on the Peninsula were largely a period of decline that culminated in the Expulsion from Spain in 1492 and the Expulsion from Portugal four years later. As David Nirenberg has written, “Violence was a central and systematic aspect of the coexistence of the majority and minorities of medieval Spain.”1 Other, recent literature emphasizes the continuities in Jewish life before and after the period 1391–1416 that witnessed the death of approximately one-third of the Jewish population and the conversion of another third to one half.2 As Mark Meyerson has noted, in Valencia and the Crown of Aragon, the horrific events of 1391 were sudden and unexpected; only in Castile can they be seen as the product of prolonged anti-Jewish activity.3 Still the 1391 pogroms were preceded by attacks on Jews during Holy Week, for example those of 1331 in Girona.4 Nearly twenty years ago Thomas Glick definedconvivencia as “coexistence, but.. -

Studies on the Structure of Gothic Cathedrals

Historical Constructions, P.B. Lourenço, P. Roca (Eds.), Guimarães, 2001 71 Studies on the structure of Gothic Cathedrals Pere Roca Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Department of Construction Engineering, Barcelona, Spain ABSTRACT: The study of three Gothic Cathedrals is presented with a discussion on the results obtained with regard to their structural features and present condition. The paper focuses on the significant difficulties that the analysts may encounter in the attempt of evaluating historical structures. These difficulties stem from the importance of historical facts (historical genesis, construction process, and possible natural or anthropic actions affecting the construction throughout its life time) and the need to integrate them in the analysis. The case studies of Tarazona, Barcelona and Mallorca Cathedrals are presented. Particular attention is given to Mallorca Cathedral because of the uniqueness and audacity of its structural design and because of the challenges that the analyst must face to conclude about its actual condition and long-tem stability. 1 CONSIDERATIONS ON THE ANALYSIS OF ANCIENT CONSTRUCTIONS One of the main elements of the European architectural heritage is found in the significant number of Gothic churches and cathedrals built during the last period of the Middle Age. Preserving these constructions requires a certain understanding of their structural features and stability condition; this, in turn, requires a certain knowledge of their material, construction and resisting nature. However, the attempt to understand a complex ancient construction, such as a Gothic cathedral, based on modern techniques and concepts, encounters important difficulties stemming from both practical and theoretical causes. Among the difficulties of practical character is the virtual impossibility of obtaining a detailed knowledge of the properties of the materials, construction details and internal composition. -

News 7 Tesoros Materiales-Angles

7 TREASURES OF THE CULTURAL HERITAGE OF THE STATE OF COLIMA MEXICO July 2013 The International Bureau of Cultural Capitals Ronda Universitat, 7 E-08007 Barcelona ℡ +34-934123294 [email protected] www.ibocc.org WORLD HERITAGE CULTURAL TREASURES The International Bureau of Cultural Capitals has developed a spe- cial project that establishes a list of the most representative local cul- tural “treasures” to be considered as “World Heritage Cultural Treasures." The purpose of this endeavor is to select, promote and communica- te the cultural heritage of a given territory, in order to promote local culture and tourism in an innovating way. This initiative also aims at establishing new touristic routes that engage visitors in learning about the rich cultural heritage of a place with an entertaining educational focus, while promoting local participation. A "territory" is defined as a place where political, geographical, administrative and/or historical coherence coexist. Therefore, for this purpose, cities, regions, provinces, states, nations, etc. are conside- red territories. Campaigns to gather the list of potential “World Heritage Cultural Treasures" developed by the International Bureau of Cultural Capitals have driven strong local participation, as well as national and inter- national media impact. Any “territory” should contact the International Bureau of Cultural Capitals via email in order to partici- pate in the “World Heritage Cultural Treasure" initiative. In order to select the cultural treasures of a territory, a three-fold campaign takes place. First, local citizens have the opportunity to submit a particular “treasure” as contender to the local World Heritage Cultural Treasure list. During the second phase, all potential treasures undergo a selection through a local voting system. -

Aesthetic Attitudes in Gothic Art: Thoughts on Girona Cathedral Actitudes Estéticas En El Arte Gótico Pensamientos Sobre La

[Recepción del artículo: 16/06/2019] [Aceptación del artículo revisado: 27/07/2019] AESTHETIC ATTITUDES IN GOTHIC ART: THOUGHTS ON GIRONA CATHEDRAL ACTITUDES ESTÉTICAS EN EL ARTE GÓTICO: PENSAMIENTOS SOBRE LA CATEDRAL DE GERONA PAUL BINSKI Cambridge University [email protected] ABSTRACT The aim of this paper is to explore aspects of medieval aesthetic experience and criticism of architecture by means of the documented Catalan and Latin expertise held at Girona Cathedral in 1416-17. Medieval documentation of this type is relatively rare. Having outlined the cases made by the architects summoned to give their opinions on the development of the cathedral, the discussion considers three particular junctures. The first is that of illumination and affect, particularly jucunditas and laetitia; the second is that of nobility and magnificence; and the third is the juncture of the palace and church. I suggest that there is significant common ground between secular and religious buildings in regard to aesthetic experience and verbal articulation. Arguing against comprehensive aesthetic and theological orders of thought and experience, and in favour of the occasional character of medieval experience (that is, the sense in which experience should be understood within a particular set of circumstances, appropriately), I conclude that much of the known language of this sort sits ill with Romantic and post-Romantic concepts of the Sublime. KEYWORDS: Girona cathedral, Gothic, expertise, affects, nobility, magnificence, Sublime RESUMEN El objetivo de este trabajo es explorar aspectos de la experiencia estética medieval y la crítica de la arquitectura a través de las visuras redactadas en catalán y en latín, que tuvieron lugar en la Catedral de Girona en 1416-1417. -

Master Thesis Cami De Sant Jaume

Master Thesis Business writing in academic institution. Cami de Sant Jaume: From Port de la Selva till Montserrat Proposition Model of development of touristic destination. Presented By: Polina Balakina Tutor: Carmen Velez Casellas Universitat de Girona, Spain Faculty of Tourism Prologue. Adventure of travelling is new knowledge, feelings, emotions and acquaintances; frightening, challenging and amazing experience. History of tourism industry as we know it today started with the first one-day package tour created by Thomas Cook in 1841. It has developed tremendously since then and is recognized by UNWTO (2016) to be the third export category after fuels and chemicals worldwide. But, with development of mass tourism, the sense of travel as a challenging and refreshing experience vanished. Great masses of tourists spend vacations in crowded spots and do similar activities. Such concentrations of visitors in certain places and time periods cause damage to local communities, environment and tourist´s perception of vacation. Current tendency in contemporary tourism in Europe, particularly Spain and especially Catalonia is sustainable development of touristic destinations, which means the use of resources for economic development in such a way that they are not damaged, but conserved and restored for future generations. This tendency involves development of sustainable touristic products that diffuse tourism demand and supply equally in terms of geography and seasonality. My Master Thesis is dedicated to a particular type of touristic activity that fits perfectly the criteria described above - route-based trekking. It is gradually becoming popular with travellers. It consists of walking from one place to another on a pre-arranged route for a prolonged period of time. -

Culture and Society in Medieval Galicia

Culture and Society in Medieval Galicia A Cultural Crossroads at the Edge of Europe Edited and Translated by James D’Emilio LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV <UN> Contents Preface ix Acknowledgments xxiv List of Figures, Maps, and Tables XXVI Abbreviations xxxii List of Contributors xxxviii Part 1: The Paradox of Galicia A Cultural Crossroads at the Edge of Europe 1 The Paradox of Galicia A Cultural Crossroads at the Edge of Europe 3 James D’Emilio Part 2: The Suevic Kingdom Between Roman Gallaecia and Modern Myth Introduction to Part 2 126 2 The Suevi in Gallaecia An Introduction 131 Michael Kulikowski 3 Gallaecia in Late Antiquity The Suevic Kingdom and the Rise of Local Powers 146 P. C. Díaz and Luis R. Menéndez-Bueyes 4 The Suevic Kingdom Why Gallaecia? 176 Fernando López Sánchez 5 The Church in the Suevic Kingdom (411–585 ad) 210 Purificación Ubric For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV <UN> vi Contents Part 3: Early Medieval Galicia Tradition and Change Introduction to Part 3 246 6 The Aristocracy and the Monarchy in Northwest Iberia between the Eighth and the Eleventh Century 251 Amancio Isla 7 The Charter of Theodenandus Writing, Ecclesiastical Culture, and Monastic Reform in Tenth- Century Galicia 281 James D’ Emilio 8 From Galicia to the Rhône Legal Practice in Northern Spain around the Year 1000 343 Jeffrey A. Bowman Part 4: Galicia in the Iberian Kingdoms From Center to Periphery? Introduction to Part 4 362 9 The Making of Galicia in Feudal Spain (1065–1157) 367 Ermelindo Portela 10 Galicia and the Galicians in the Latin Chronicles of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries 400 Emma Falque 11 The Kingdom of Galicia and the Monarchy of Castile-León in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries 429 Francisco Javier Pérez Rodríguez For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV <UN> Contents vii Part 5: Compostela, Galicia, and Europe Galician Culture in the Age of the Pilgrimage Introduction to Part 5 464 12 St. -

Ge-Conservación Nº 6/ 2014

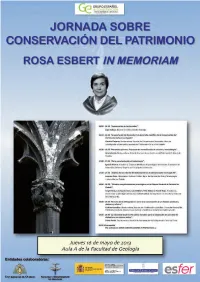

Caracterización y conservación de los materiales pétreos: Bibliografía del Grupo de Investigación de la Universidad de Oviedo. Fco. Javier Alonso, Jorge Ordaz y Luis Valdeón. Resumen: Se presenta un inventario de publicaciones y documentos realizados por el “Grupo de Alteración” de la Universidad de Oviedo, dirigido por la profesora Rosa María Esbert, desde sus inicios a finales de los años 70. Los temas estudiados giran en torno a la caracterización, deterioro y conservación de los materiales pétreos utilizados en edificación, en especial en mo- numentos y patrimonio arquitectónico. Se recogen cronológicamente distintos tipos de documentos: libros y capítulos de libros, artículos de publicaciones periódicas, comunicaciones presentadas en congresos y documentos inéditos (memorias de investigación resultado de proyectos y contratos). Se indica cuales son actualmente de libre disposición en la red (normalmente las publicaciones periódicas), si bien todos ellos pueden consultarse en el Área de Petrología y Geoquímica (Departamento de Geología, Universidad de Oviedo). Palabras clave: piedra, alteración, deterioro, durabilidad, conservación, restauración, monumentos, patrimonio. Characterization and conservation of stone materials: Bibliography of Research Group of Oviedo University. Abstract: An inventory of publications and documents made by the “Group of Alteration” from University of Oviedo, led by professor Rosa María Esbert, from its beginnings in the late ‘70s is shown. Topics studied include characterization, deterioration and conser- vation of stone materials used in building, especially in monuments and architectural heritage. Diferent types of documents are collected chronologically: books and book chapters, articles in periodicals, papers presented in congresses and unpublished docu- ments (research reports from projects and contracts). Documents that are freely available at present on the net (usually periodicals) are showed, although all of them are available on the Area of Petrology and Geochemistry (Department of Geology, University of Oviedo).