ICMA News...And More Spring 2019, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AN ARMENIAN MEDITERRANEAN Words and Worlds in Motion CHAPTER 5

EDITED BY KATHRYN BABAYAN AND MICHAEL PIFER AN ARMENIAN MEDITERRANEAN Words and Worlds in Motion CHAPTER 5 From “Autonomous” to “Interactive” Histories: World History’s Challenge to Armenian Studies Sebouh David Aslanian In recent decades, world historians have moved away from more conventional studies of nations and national states to examine the role of transregional networks in facilitating hemispheric interactions and connectedness between This chapter was mostly written in the summer of 2009 and 2010 and episodically revised over the past few years. Earlier iterations were presented at Armenian Studies workshops at the University of California, Los Angeles in 2009, and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor in 2012 and 2015. I am grateful to the conveners of the workshops for the invitation and feedback. I would also like to thank especially Houri Berberian, Jirair Libaridian, David Myers, Stephen H. Rapp, Khachig Tölölyan, Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Sarah Abrevaya Stein, Kathryn Babayan, Richard Antaramian, Giusto Traina, and Marc Mamigonian for their generous comments. As usual, I alone am responsible for any shortcomings. S. D. Aslanian (*) University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA © The Author(s) 2018 81 K. Babayan, M. Pifer (eds.), An Armenian Mediterranean, Mediterranean Perspectives, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72865-0_5 82 S. D. ASLANIAN cultures and regions.1 This shift from what may be called the optic of the nation(-state) to a global optic has enabled historians to examine large- scale historical processes -

Armenia, Republic of | Grove

Grove Art Online Armenia, Republic of [Hayasdan; Hayq; anc. Pers. Armina] Lucy Der Manuelian, Armen Zarian, Vrej Nersessian, Nonna S. Stepanyan, Murray L. Eiland and Dickran Kouymjian https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T004089 Published online: 2003 updated bibliography, 26 May 2010 Country in the southern part of the Transcaucasian region; its capital is Erevan. Present-day Armenia is bounded by Georgia to the north, Iran to the south-east, Azerbaijan to the east and Turkey to the west. From 1920 to 1991 Armenia was a Soviet Socialist Republic within the USSR, but historically its land encompassed a much greater area including parts of all present-day bordering countries (see fig.). At its greatest extent it occupied the plateau covering most of what is now central and eastern Turkey (c. 300,000 sq. km) bounded on the north by the Pontic Range and on the south by the Taurus and Kurdistan mountains. During the 11th century another Armenian state was formed to the west of Historic Armenia on the Cilician plain in south-east Asia Minor, bounded by the Taurus Mountains on the west and the Amanus (Nur) Mountains on the east. Its strategic location between East and West made Historic or Greater Armenia an important country to control, and for centuries it was a battlefield in the struggle for power between surrounding empires. Periods of domination and division have alternated with centuries of independence, during which the country was divided into one or more kingdoms. Page 1 of 47 PRINTED FROM Oxford Art Online. © Oxford University Press, 2019. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/04/2021 08:59:36AM Via Free Access

Chapter 12 Aristocrats, Mercenaries, Clergymen and Refugees: Deliberate and Forced Mobility of Armenians in the Early Medieval Mediterranean (6th to 11th Century a.d.) Johannes Preiser-Kapeller 1 Introduction Armenian mobility in the early Middle Ages has found some attention in the scholarly community. This is especially true for the migration of individuals and groups towards the Byzantine Empire. A considerable amount of this re- search has focused on the carriers and histories of individual aristocrats or noble families of Armenian origin. The obviously significant share of these in the Byzantine elite has even led to formulations such as Byzantium being a “Greco-Armenian Empire”.1 While, as expected, evidence for the elite stratum is relatively dense, larger scale migration of members of the lower aristocracy (“azat”, within the ranking system of Armenian nobility, see below) or non- aristocrats (“anazat”) can also be traced with regard to the overall movement of groups within the entire Byzantine sphere. In contrast to the nobility, however, the life stories and strategies of individuals of these backgrounds very rarely can be reconstructed based on our evidence. In all cases, the actual signifi- cance of an “Armenian” identity for individuals and groups identified as “Ar- menian” by contemporary sources or modern day scholarship (on the basis of 1 Charanis, “Armenians in the Byzantine Empire”, passim; Charanis, “Transfer of population”; Toumanoff, “Caucasia and Byzantium”, pp. 131–133; Ditten, Ethnische Verschiebungen, pp. 124–127, 134–135; Haldon, “Late Roman Senatorial Elite”, pp. 213–215; Whitby, “Recruitment”, pp. 87–90, 99–101, 106–110; Isaac, “Army in the Late Roman East”, pp. -

Reflections on Fieldwork in the Region of Ani Christina Maranci I Study the Medieval Armenian Monuments—Churche

In the Traces: Reflections on Fieldwork in the Region of Ani Christina Maranci I study the medieval Armenian monuments—churches, monasteries, fortresses, palaces, and more—in what is now eastern Turkey (what many call western Arme- nia). For me, this region is at once the most beautiful, and most painful, place on earth. I am the grandchild of survivors of the Armenian Genocide of 1915–22, in which Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire suffered mass deportation and extermination: a crime that still goes unrecognized by the Turkish state.1 Scholars have characterized the Armenian monuments in Turkey as physical traces of their lost homeland.2 While my scholarship addresses these sites as historical and archi- tectural/artistic phenomena, that work does not often capture the moods and emotions I feel when I am there.3 I hope to offer here a sense of the more personal dimensions of firsthand work with the buildings and their landscapes. Many important medieval Armenian monuments stand on and around the closed international border between the Republics of Turkey and Armenia. Some of them are accessible to tourists, while others, like the church of Mren, remain forbidden, as they lie within or too close to the military zone. Dated to circa 638, and once part of the princely territory of the Kamsarakan family, Mren became the summer residence of the royal Armenian Bagratids in the tenth century.4 Once surrounded by a network of buildings, vineyards, and roads, now the church stands alone. Figure 1 illustrates the Armenian high plateau: deforested from antiquity, it is a rocky tableland lacerated by gorges and ringed with mountain chains. -

Questions for Art of Medieval Spain

www.YoYoBrain.com - Accelerators for Memory and Learning Questions for Art of Medieval Spain Category: Default - (74 questions) Alabaster sculpture of Tanit/Astarte, nicknamed "Dama de Galera," Madrid, Museo Arqueológico, 7th c BCE -Phinecean object that found home in Iberian religious practices -Phineceans: eastern culture; experts in maritime travel; traded with Iberian locals; began settling in coastal cities around mouth of the mediterranean around 8th cen. BCE Sculpture of Askepios, from Empùries, 2 c BCE -Greek Empuries -from Sanctuary of Askepios (God of Medicine) Dama de Baza, 4th c. CE -reminiscent of ancient Greek Chios Kore -from native culture of Iberia: culturally receptive but politically resistant to invading groups; independent tribes) -rise of votive figure echo to the Phineceans Head of Augustus, early 1st c. CE -sculpture from Merida (sculptures from this area were among the finest on the peninsula) -Merida (aka Augusta Emerita) was a military settlement; founded by Augustus for retired soldiers; not founded on a pre-existing site which is different from ordinary Roman towns in Spain; became a politically important city Mérida, theater, inscr. 15-16 BC -attached to amphitheater; deliberate connection -attributed to Augustus -well preserved -partly reconstructed (scenae frons- elaborate, built later during Hadrian period) Tarragona (Tarraco), Arch of Bará, 2nd c CE -Tarragona was capital of Eastern Roman Spain (being on top of a hill, it was hard to attack and therefore a good place for a capital) -The arch is just outside -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

THE MAN AND THE MYTH: HERACLIUS AND THE LEGEND OF THE LAST ROMAN EMPEROR By CHRISTOPHER BONURA A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Christopher Bonura 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my adviser, Dr. Andrea Sterk, for all the help and support she has given me, not just for this thesis, but for her patience and guidance throughout my time as her student. I would never have made it to this point without her help. I would like to thank Dr. Florin Curta for introducing me to the study of medieval history, for being there for me with advice and encouragement. I would like to thank Dr. Bonnie Effros for all her help and support, and for letting me clutter the Center for the Humanities office with all my books. And I would like to thank Dr. Nina Caputo, who has always been generous with suggestions and useful input, and who has helped guide my research. My parents and brother also deserve thanks. In addition, I feel it is necessary to thank the Interlibrary loan office, for all I put them through in getting books for me. Finally, I would like to thank all my friends and colleagues in the history department, whose support and friendship made my time studying at the University of Florida bearable, and often even fun, especially Anna Lankina-Webb, Rebecca Devlin, Ralph Patrello, Alana Lord, Eleanor Deumens, Robert McEachnie, Sean Hill, Sean Platzer, Bryan Behl, Andrew Welton, and Miller Krause. -

Medieval Mediterranean Influence in the Treasury of San Marco Claire

Circular Inspirations: Medieval Mediterranean Influence in the Treasury of San Marco Claire Rasmussen Thesis Submitted to the Department of Art For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts 2019 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. Introduction………………………...………………………………………….3 II. Myths……………………………………………………………………….....9 a. Historical Myths…………………………………………………………...9 b. Treasury Myths…………………………………………………………..28 III. Mediums and Materials………………………………………………………34 IV. Mergings……………………………………………………………………..38 a. Shared Taste……………………………………………………………...40 i. Global Networks…………………………………………………40 ii. Byzantine Influence……………………………………………...55 b. Unique Taste……………………………………………………………..60 V. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………...68 VI. Appendix………………………………………………………………….….73 VII. List of Figures………………………………………………………………..93 VIII. Works Cited…………………………………………………...……………104 3 I. Introduction In the Treasury of San Marco, there is an object of three parts (Figure 1). Its largest section piece of transparent crystal, carved into the shape of a grotto. Inside this temple is a metal figurine of Mary, her hands outstretched. At the bottom, the crystal grotto is fixed to a Byzantine crown decorated with enamels. Each part originated from a dramatically different time and place. The crystal was either carved in Imperial Rome prior to the fourth century or in 9th or 10th century Cairo at the time of the Fatimid dynasty. The figure of Mary is from thirteenth century Venice, and the votive crown is Byzantine, made by craftsmen in the 8th or 9th century. The object resembles a Frankenstein’s monster of a sculpture, an amalgamation of pieces fused together that were meant to used apart. But to call it a Frankenstein would be to suggest that the object’s parts are wildly mismatched and clumsily sewn together, and is to dismiss the beauty of the crystal grotto, for each of its individual components is finely made: the crystal is intricately carved, the figure of Mary elegant, and the crown vivid and colorful. -

Cilician Armenian Mediation in Crusader-Mongol Politics, C.1250-1350

HAYTON OF KORYKOS AND LA FLOR DES ESTOIRES: CILICIAN ARMENIAN MEDIATION IN CRUSADER-MONGOL POLITICS, C.1250-1350 by Roubina Shnorhokian A thesis submitted to the Department of History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (January, 2015) Copyright ©Roubina Shnorhokian, 2015 Abstract Hayton’s La Flor des estoires de la terre d’Orient (1307) is typically viewed by scholars as a propagandistic piece of literature, which focuses on promoting the Ilkhanid Mongols as suitable allies for a western crusade. Written at the court of Pope Clement V in Poitiers in 1307, Hayton, a Cilician Armenian prince and diplomat, was well-versed in the diplomatic exchanges between the papacy and the Ilkhanate. This dissertation will explore his complex interests in Avignon, where he served as a political and cultural intermediary, using historical narrative, geography and military expertise to persuade and inform his Latin audience of the advantages of allying with the Mongols and sending aid to Cilician Armenia. This study will pay close attention to the ways in which his worldview as a Cilician Armenian informed his perceptions. By looking at a variety of sources from Armenian, Latin, Eastern Christian, and Arab traditions, this study will show that his knowledge was drawn extensively from his inter-cultural exchanges within the Mongol Empire and Cilician Armenia’s position as a medieval crossroads. The study of his career reflects the range of contacts of the Eurasian world. ii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the financial support of SSHRC, the Marjorie McLean Oliver Graduate Scholarship, OGS, and Queen’s University. -

La Structure De La Cathédrale De Chartres

La structure de la cathédrale de Chartres Andrew Tallon Le stigmate d’une sur-construction, d’une masse inutile, voire d’une certaine maladresse pèse toujours sur l’interprétation de la structure de la cathédrale de Chartres1. Il est temps aujourd’hui de dépasser ces explications malheureuses et de réhabiliter la réception de la structure du bâtiment, à l’image d’autres facettes révélées au cours de ces dernières années. La structure de la cathédrale Chartres ne doit plus être envisagée, dans le cadre de comparaisons unilatérales, en faveur d’un éloge du premier maître de la cathé- drale de Bourges2, ni limitée à un indice chronologique pratique sinon trompeur au cœur d’un débat perdurant depuis plus d’une cinquantaine d’années. Elle ne doit pas plus être envisagée comme le produit d’une peur intense de l’échec face à un déploiement inédit de fenêtres hautes. Au contraire, la structure de la cathé- drale de Chartres doit être vue dans le contexte d’un ensemble architecturale : elle résulte à la fois d’un système précisément pensé, voire brillant, conçu non seulement pour résister parfaitement aux forces affaiblissantes du temps et de la gravité – ce que nous nous efforcerons de montrer à l’aide d’un relevé laser haute-définition entrepris en juin 2011 (fig. 1 et 2) – mais aussi d’une structure illusionniste, une évocation puissante de la sublime architecturale3. 1.– Voir, en particulier, R. Mark et W. Clark, « Gothic Structural Experimentation », Scientific American, 251, 5, 1984, p. 176-185. 2.– R. Mark, Experiments in Gothic Structure, Cambridge, Mass., 1982, p. -

Diocesis Hispaniarum (3Rd-5Th Century)

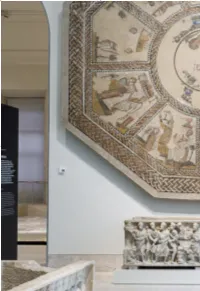

003 ROMA_english_Maquetación 1 21/02/14 11:33 Página 64 003 ROMA_english_Maquetación 1 21/02/14 11:33 Página 65 From Late Antiquity to Middle Age 004 MEDIEVAL_english_Maquetación 1 21/02/14 11:42 Página 66 Diocesis Hispaniarum (3rd-5th Century) The third century was a period of political and economic instability for the Roman Empire, which culminated with the reign of Diocletian. Under his rule, Hispania was divided into five provinces which together formed the Diocesis Hispaniarum. The fourth century brought a revival of economic prosperity, especially during the reign of the Hispano-Roman emperor Theo- dosius. The growing importance of the rural villas, the new residences of the Hispano-Roman aristocracy, would mark the course of the fourth and fifth centuries. In 380 Theodosius declared Christianity the empire’s official religion, crea- 66 ting a new ideological instrument of power with far-reaching political, ad- ministrative and social consequences. The origins of Christianity in Hispania are heterogeneous, with influences pouring in from North Africa, Rome and other places where important communities had existed since the third cen- tury. Everyday objects like the ones in the display case incorporated Christian symbols such as the Chi-Rho. The exhibition also features sarcophagi with relief decoration, a mosaic memorial plaque and gravestone inscriptions in memory of the dead. Reccesvinth’s crown (The Guarrazar Hoard) > 004 MEDIEVAL_english_Maquetación 1 21/02/14 11:42 Página 67 004 MEDIEVAL_english_Maquetación 1 21/02/14 11:42 Página 68 The Visigothic Kingdom of Toledo (6th-8th Century) After being defeated by the Franks at the Battle of Vouillé (507), the Visi- goths consolidated their power on the Iberian Peninsula and established To- ledo as their capital. -

Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 5 Issue 1 2015 Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture (Volume 5, Issue 1) Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation . "Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture (Volume 5, Issue 1)." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5, 1 (2015). https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol5/iss1/7 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. et al. Welcome It’s been some time, but we think that this marvelous double issue here was worth the wait. So, welcome to the Autumn Current Issue 2014 and Spring 2015 issues of Peregrinations: Journal of Photobank Medieval Art & Architecture. The first issue is devoted to how identity is signified by material and visual expressions Submission connected to one particular location, here the Flemish Low Guidelines Countries during the High Middle Ages. Edited by Elizabeth Moore Hunt and Richard A. Leson, the collection of essays Organizations touch on imagery and language from heraldry to specialized fortification reflecting a complex interaction in terms of Discoveries tradition and new expectations. Jeff Rider examines how the author of Genealogia Flandrensium comitum creates a new history from competing sources, while Bailey K. -

Building Churches in Armenia: Art at the Borders of Empire and the Edge of the Canon

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 Building Churches in Armenia: Art at the Borders of Empire and the Edge of the Canon Christina Maranci To cite this article: Christina Maranci (2006) Building Churches in Armenia: Art at the Borders of Empire and the Edge of the Canon, The Art Bulletin, 88:4, 656-675, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2006.10786313 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2006.10786313 Published online: 03 Apr 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 74 Citing articles: 3 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Building Churches in Armenia: Art at the Borders of Empire and the Edge of the Canon Christina Maranci Between the index entries for “Arles” and “arms and armor” ence of multiple and distinct voices within a single voice or in most general studies of medieval art is a thin rectangle of language) and ambiguity became shrewd diplomatic devices. white space. For those seeking “Armenia,” this interval is as The Armenian structures thus can generate an alternative familiar as it is bleak, for the cultures of the Transcaucasus picture of the early medieval Christian East, one in which typically occupy a marginal position, if any, within the study military conflict activated, rather than dulled, the visual and of the Middle Ages. One might blame realities of geography verbal response. and language: a stony tableland wedged between Byzantium These churches present the additional benefit of furnish- and the Sasanian and Islamic Near East, home to a tongue ing architectural evidence from an era often considered vir- unintelligible to Greek or Latin ears, Armenia could be per- tually bereft of monuments.