Statistical Thermodynamics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interaction of the Past of Parallel Universes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CERN Document Server Interaction of the Past of parallel universes Alexander K. Guts Department of Mathematics, Omsk State University 644077 Omsk-77 RUSSIA E-mail: [email protected] October 26, 1999 ABSTRACT We constructed a model of five-dimensional Lorentz manifold with foliation of codimension 1 the leaves of which are four-dimensional space-times. The Past of these space-times can interact in macroscopic scale by means of large quantum fluctuations. Hence, it is possible that our Human History consists of ”somebody else’s” (alien) events. In this article the possibility of interaction of the Past (or Future) in macroscopic scales of space and time of two different universes is analysed. Each universe is considered as four-dimensional space-time V 4, moreover they are imbedded in five- dimensional Lorentz manifold V 5, which shall below name Hyperspace. The space- time V 4 is absolute world of events. Consequently, from formal standpoints any point-event of this manifold V 4, regardless of that we refer it to Past, Present or Future of some observer, is equally available to operate with her.Inotherwords, modern theory of space-time, rising to Minkowsky, postulates absolute eternity of the World of events in the sense that all events exist always. Hence, it is possible interaction of Present with Past and Future as well as Past can interact with Future. Question is only in that as this is realized. The numerous articles about time machine show that our statement on the interaction of Present with Past is not fantasy, but is subject of the scientific study. -

Canonical Ensemble

ME346A Introduction to Statistical Mechanics { Wei Cai { Stanford University { Win 2011 Handout 8. Canonical Ensemble January 26, 2011 Contents Outline • In this chapter, we will establish the equilibrium statistical distribution for systems maintained at a constant temperature T , through thermal contact with a heat bath. • The resulting distribution is also called Boltzmann's distribution. • The canonical distribution also leads to definition of the partition function and an expression for Helmholtz free energy, analogous to Boltzmann's Entropy formula. • We will study energy fluctuation at constant temperature, and witness another fluctuation- dissipation theorem (FDT) and finally establish the equivalence of micro canonical ensemble and canonical ensemble in the thermodynamic limit. (We first met a mani- festation of FDT in diffusion as Einstein's relation.) Reading Assignment: Reif x6.1-6.7, x6.10 1 1 Temperature For an isolated system, with fixed N { number of particles, V { volume, E { total energy, it is most conveniently described by the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble, which is a uniform distribution between two constant energy surfaces. const E ≤ H(fq g; fp g) ≤ E + ∆E ρ (fq g; fp g) = i i (1) mc i i 0 otherwise Statistical mechanics also provides the expression for entropy S(N; V; E) = kB ln Ω. In thermodynamics, S(N; V; E) can be transformed to a more convenient form (by Legendre transform) of Helmholtz free energy A(N; V; T ), which correspond to a system with constant N; V and temperature T . Q: Does the transformation from N; V; E to N; V; T have a meaning in statistical mechanics? A: The ensemble of systems all at constant N; V; T is called the canonical NVT ensemble. -

Magnetism, Magnetic Properties, Magnetochemistry

Magnetism, Magnetic Properties, Magnetochemistry 1 Magnetism All matter is electronic Positive/negative charges - bound by Coulombic forces Result of electric field E between charges, electric dipole Electric and magnetic fields = the electromagnetic interaction (Oersted, Maxwell) Electric field = electric +/ charges, electric dipole Magnetic field ??No source?? No magnetic charges, N-S No magnetic monopole Magnetic field = motion of electric charges (electric current, atomic motions) Magnetic dipole – magnetic moment = i A [A m2] 2 Electromagnetic Fields 3 Magnetism Magnetic field = motion of electric charges • Macro - electric current • Micro - spin + orbital momentum Ampère 1822 Poisson model Magnetic dipole – magnetic (dipole) moment [A m2] i A 4 Ampere model Magnetism Microscopic explanation of source of magnetism = Fundamental quantum magnets Unpaired electrons = spins (Bohr 1913) Atomic building blocks (protons, neutrons and electrons = fermions) possess an intrinsic magnetic moment Relativistic quantum theory (P. Dirac 1928) SPIN (quantum property ~ rotation of charged particles) Spin (½ for all fermions) gives rise to a magnetic moment 5 Atomic Motions of Electric Charges The origins for the magnetic moment of a free atom Motions of Electric Charges: 1) The spins of the electrons S. Unpaired spins give a paramagnetic contribution. Paired spins give a diamagnetic contribution. 2) The orbital angular momentum L of the electrons about the nucleus, degenerate orbitals, paramagnetic contribution. The change in the orbital moment -

2D Potts Model Correlation Lengths

KOMA Revised version May D Potts Mo del Correlation Lengths Numerical Evidence for = at o d t Wolfhard Janke and Stefan Kappler Institut f ur Physik Johannes GutenbergUniversitat Mainz Staudinger Weg Mainz Germany Abstract We have studied spinspin correlation functions in the ordered phase of the twodimensional q state Potts mo del with q and at the rstorder transition p oint Through extensive Monte t Carlo simulations we obtain strong numerical evidence that the cor relation length in the ordered phase agrees with the exactly known and recently numerically conrmed correlation length in the disordered phase As a byproduct we nd the energy moments o t t d in the ordered phase at in very go o d agreement with a recent large t q expansion PACS numbers q Hk Cn Ha hep-lat/9509056 16 Sep 1995 Introduction Firstorder phase transitions have b een the sub ject of increasing interest in recent years They play an imp ortant role in many elds of physics as is witnessed by such diverse phenomena as ordinary melting the quark decon nement transition or various stages in the evolution of the early universe Even though there exists already a vast literature on this sub ject many prop erties of rstorder phase transitions still remain to b e investigated in detail Examples are nitesize scaling FSS the shap e of energy or magnetization distributions partition function zeros etc which are all closely interrelated An imp ortant approach to attack these problems are computer simulations Here the available system sizes are necessarily -

Full and Unbiased Solution of the Dyson-Schwinger Equation in the Functional Integro-Differential Representation

PHYSICAL REVIEW B 98, 195104 (2018) Full and unbiased solution of the Dyson-Schwinger equation in the functional integro-differential representation Tobias Pfeffer and Lode Pollet Department of Physics, Arnold Sommerfeld Center for Theoretical Physics, University of Munich, Theresienstrasse 37, 80333 Munich, Germany (Received 17 March 2018; revised manuscript received 11 October 2018; published 2 November 2018) We provide a full and unbiased solution to the Dyson-Schwinger equation illustrated for φ4 theory in 2D. It is based on an exact treatment of the functional derivative ∂/∂G of the four-point vertex function with respect to the two-point correlation function G within the framework of the homotopy analysis method (HAM) and the Monte Carlo sampling of rooted tree diagrams. The resulting series solution in deformations can be considered as an asymptotic series around G = 0 in a HAM control parameter c0G, or even a convergent one up to the phase transition point if shifts in G can be performed (such as by summing up all ladder diagrams). These considerations are equally applicable to fermionic quantum field theories and offer a fresh approach to solving functional integro-differential equations beyond any truncation scheme. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevB.98.195104 I. INTRODUCTION was not solved and differences with the full, exact answer could be seen when the correlation length increases. Despite decades of research there continues to be a need In this work, we solve the full DSE by writing them as a for developing novel methods for strongly correlated systems. closed set of integro-differential equations. Within the HAM The standard Monte Carlo approaches [1–5] are convergent theory there exists a semianalytic way to treat the functional but suffer from a prohibitive sign problem, scaling exponen- derivatives without resorting to an infinite expansion of the tially in the system volume [6]. -

Projective Geometry: a Short Introduction

Projective Geometry: A Short Introduction Lecture Notes Edmond Boyer Master MOSIG Introduction to Projective Geometry Contents 1 Introduction 2 1.1 Objective . .2 1.2 Historical Background . .3 1.3 Bibliography . .4 2 Projective Spaces 5 2.1 Definitions . .5 2.2 Properties . .8 2.3 The hyperplane at infinity . 12 3 The projective line 13 3.1 Introduction . 13 3.2 Projective transformation of P1 ................... 14 3.3 The cross-ratio . 14 4 The projective plane 17 4.1 Points and lines . 17 4.2 Line at infinity . 18 4.3 Homographies . 19 4.4 Conics . 20 4.5 Affine transformations . 22 4.6 Euclidean transformations . 22 4.7 Particular transformations . 24 4.8 Transformation hierarchy . 25 Grenoble Universities 1 Master MOSIG Introduction to Projective Geometry Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Objective The objective of this course is to give basic notions and intuitions on projective geometry. The interest of projective geometry arises in several visual comput- ing domains, in particular computer vision modelling and computer graphics. It provides a mathematical formalism to describe the geometry of cameras and the associated transformations, hence enabling the design of computational ap- proaches that manipulates 2D projections of 3D objects. In that respect, a fundamental aspect is the fact that objects at infinity can be represented and manipulated with projective geometry and this in contrast to the Euclidean geometry. This allows perspective deformations to be represented as projective transformations. Figure 1.1: Example of perspective deformation or 2D projective transforma- tion. Another argument is that Euclidean geometry is sometimes difficult to use in algorithms, with particular cases arising from non-generic situations (e.g. -

Chapter 3. Second and Third Law of Thermodynamics

Chapter 3. Second and third law of thermodynamics Important Concepts Review Entropy; Gibbs Free Energy • Entropy (S) – definitions Law of Corresponding States (ch 1 notes) • Entropy changes in reversible and Reduced pressure, temperatures, volumes irreversible processes • Entropy of mixing of ideal gases • 2nd law of thermodynamics • 3rd law of thermodynamics Math • Free energy Numerical integration by computer • Maxwell relations (Trapezoidal integration • Dependence of free energy on P, V, T https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trapezoidal_rule) • Thermodynamic functions of mixtures Properties of partial differential equations • Partial molar quantities and chemical Rules for inequalities potential Major Concept Review • Adiabats vs. isotherms p1V1 p2V2 • Sign convention for work and heat w done on c=C /R vm system, q supplied to system : + p1V1 p2V2 =Cp/CV w done by system, q removed from system : c c V1T1 V2T2 - • Joule-Thomson expansion (DH=0); • State variables depend on final & initial state; not Joule-Thomson coefficient, inversion path. temperature • Reversible change occurs in series of equilibrium V states T TT V P p • Adiabatic q = 0; Isothermal DT = 0 H CP • Equations of state for enthalpy, H and internal • Formation reaction; enthalpies of energy, U reaction, Hess’s Law; other changes D rxn H iD f Hi i T D rxn H Drxn Href DrxnCpdT Tref • Calorimetry Spontaneous and Nonspontaneous Changes First Law: when one form of energy is converted to another, the total energy in universe is conserved. • Does not give any other restriction on a process • But many processes have a natural direction Examples • gas expands into a vacuum; not the reverse • can burn paper; can't unburn paper • heat never flows spontaneously from cold to hot These changes are called nonspontaneous changes. -

Einstein Solid 1 / 36 the Results 2

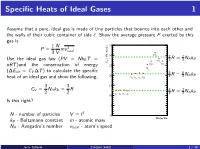

Specific Heats of Ideal Gases 1 Assume that a pure, ideal gas is made of tiny particles that bounce into each other and the walls of their cubic container of side `. Show the average pressure P exerted by this gas is 1 N 35 P = mv 2 3 V total SO 30 2 7 7 (J/K-mole) R = NAkB Use the ideal gas law (PV = NkB T = V 2 2 CO2 C H O CH nRT )and the conservation of energy 25 2 4 Cl2 (∆Eint = CV ∆T ) to calculate the specific 5 5 20 2 R = 2 NAkB heat of an ideal gas and show the following. H2 N2 O2 CO 3 3 15 CV = NAkB = R 3 3 R = NAkB 2 2 He Ar Ne Kr 2 2 10 Is this right? 5 3 N - number of particles V = ` 0 Molecule kB - Boltzmann constant m - atomic mass NA - Avogadro's number vtotal - atom's speed Jerry Gilfoyle Einstein Solid 1 / 36 The Results 2 1 N 2 2 N 7 P = mv = hEkini 2 NAkB 3 V total 3 V 35 30 SO2 3 (J/K-mole) V 5 CO2 C N k hEkini = NkB T H O CH 2 A B 2 25 2 4 Cl2 20 H N O CO 3 3 2 2 2 3 CV = NAkB = R 2 NAkB 2 2 15 He Ar Ne Kr 10 5 0 Molecule Jerry Gilfoyle Einstein Solid 2 / 36 Quantum mechanically 2 E qm = `(` + 1) ~ rot 2I where l is the angular momen- tum quantum number. -

Gibbs' Paradox and the Definition of Entropy

Entropy 2008, 10, 15-18 entropy ISSN 1099-4300 °c 2008 by MDPI www.mdpi.org/entropy/ Full Paper Gibbs’ Paradox and the Definition of Entropy Robert H. Swendsen Physics Department, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA E-Mail: [email protected] Received: 10 December 2007 / Accepted: 14 March 2008 / Published: 20 March 2008 Abstract: Gibbs’ Paradox is shown to arise from an incorrect traditional definition of the entropy that has unfortunately become entrenched in physics textbooks. Among its flaws, the traditional definition predicts a violation of the second law of thermodynamics when applied to colloids. By adopting Boltzmann’s definition of the entropy, the violation of the second law is eliminated, the properties of colloids are correctly predicted, and Gibbs’ Paradox vanishes. Keywords: Gibbs’ Paradox, entropy, extensivity, Boltzmann. 1. Introduction Gibbs’ Paradox [1–3] is based on a traditional definition of the entropy in statistical mechanics found in most textbooks [4–6]. According to this definition, the entropy of a classical system is given by the product of Boltzmann’s constant, k, with the logarithm of a volume in phase space. This is shown in many textbooks to lead to the following equation for the entropy of a classical ideal gas of distinguishable particles, 3 E S (E; V; N) = kN[ ln V + ln + X]; (1) trad 2 N where X is a constant. Most versions of Gibbs’ Paradox, including the one I give in this section, rest on the fact that Eq. 1 is not extensive. There is another version of Gibbs’ Paradox that involves the mixing of two gases, which I will discuss in the third section of this paper. -

![Arxiv:1910.10745V1 [Cond-Mat.Str-El] 23 Oct 2019 2.2 Symmetry-Protected Time Crystals](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4942/arxiv-1910-10745v1-cond-mat-str-el-23-oct-2019-2-2-symmetry-protected-time-crystals-304942.webp)

Arxiv:1910.10745V1 [Cond-Mat.Str-El] 23 Oct 2019 2.2 Symmetry-Protected Time Crystals

A Brief History of Time Crystals Vedika Khemania,b,∗, Roderich Moessnerc, S. L. Sondhid aDepartment of Physics, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA bDepartment of Physics, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, USA cMax-Planck-Institut f¨urPhysik komplexer Systeme, 01187 Dresden, Germany dDepartment of Physics, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey 08544, USA Abstract The idea of breaking time-translation symmetry has fascinated humanity at least since ancient proposals of the per- petuum mobile. Unlike the breaking of other symmetries, such as spatial translation in a crystal or spin rotation in a magnet, time translation symmetry breaking (TTSB) has been tantalisingly elusive. We review this history up to recent developments which have shown that discrete TTSB does takes place in periodically driven (Floquet) systems in the presence of many-body localization (MBL). Such Floquet time-crystals represent a new paradigm in quantum statistical mechanics — that of an intrinsically out-of-equilibrium many-body phase of matter with no equilibrium counterpart. We include a compendium of the necessary background on the statistical mechanics of phase structure in many- body systems, before specializing to a detailed discussion of the nature, and diagnostics, of TTSB. In particular, we provide precise definitions that formalize the notion of a time-crystal as a stable, macroscopic, conservative clock — explaining both the need for a many-body system in the infinite volume limit, and for a lack of net energy absorption or dissipation. Our discussion emphasizes that TTSB in a time-crystal is accompanied by the breaking of a spatial symmetry — so that time-crystals exhibit a novel form of spatiotemporal order. -

Near-Death Experiences and the Theory of the Extraneuronal Hyperspace

Near-Death Experiences and the Theory of the Extraneuronal Hyperspace Linz Audain, J.D., Ph.D., M.D. George Washington University The Mandate Corporation, Washington, DC ABSTRACT: It is possible and desirable to supplement the traditional neu rological and metaphysical explanatory models of the near-death experience (NDE) with yet a third type of explanatory model that links the neurological and the metaphysical. I set forth the rudiments of this model, the Theory of the Extraneuronal Hyperspace, with six propositions. I then use this theory to explain three of the pressing issues within NDE scholarship: the veridicality, precognition and "fear-death experience" phenomena. Many scholars who write about near-death experiences (NDEs) are of the opinion that explanatory models of the NDE can be classified into one of two types (Blackmore, 1993; Moody, 1975). One type of explana tory model is the metaphysical or supernatural one. In that model, the events that occur within the NDE, such as the presence of a tunnel, are real events that occur beyond the confines of time and space. In a sec ond type of explanatory model, the traditional model, the events that occur within the NDE are not at all real. Those events are merely the product of neurobiochemical activity that can be explained within the confines of current neurological and psychological theory, for example, as hallucination. In this article, I supplement this dichotomous view of explanatory models of the NDE by proposing yet a third type of explanatory model: the Theory of the Extraneuronal Hyperspace. This theory represents a Linz Audain, J.D., Ph.D., M.D., is a Resident in Internal Medicine at George Washington University, and Chief Executive Officer of The Mandate Corporation. -

Bose-Einstein Condensation of Photons and Grand-Canonical Condensate fluctuations

Bose-Einstein condensation of photons and grand-canonical condensate fluctuations Jan Klaers Institute for Applied Physics, University of Bonn, Germany Present address: Institute for Quantum Electronics, ETH Zürich, Switzerland Martin Weitz Institute for Applied Physics, University of Bonn, Germany Abstract We review recent experiments on the Bose-Einstein condensation of photons in a dye-filled optical microresonator. The most well-known example of a photon gas, pho- tons in blackbody radiation, does not show Bose-Einstein condensation. Instead of massively populating the cavity ground mode, photons vanish in the cavity walls when they are cooled down. The situation is different in an ultrashort optical cavity im- printing a low-frequency cutoff on the photon energy spectrum that is well above the thermal energy. The latter allows for a thermalization process in which both tempera- ture and photon number can be tuned independently of each other or, correspondingly, for a non-vanishing photon chemical potential. We here describe experiments demon- strating the fluorescence-induced thermalization and Bose-Einstein condensation of a two-dimensional photon gas in the dye microcavity. Moreover, recent measurements on the photon statistics of the condensate, showing Bose-Einstein condensation in the grandcanonical ensemble limit, will be reviewed. 1 Introduction Quantum statistical effects become relevant when a gas of particles is cooled, or its den- sity is increased, to the point where the associated de Broglie wavepackets spatially over- arXiv:1611.10286v1 [cond-mat.quant-gas] 30 Nov 2016 lap. For particles with integer spin (bosons), the phenomenon of Bose-Einstein condensation (BEC) then leads to macroscopic occupation of a single quantum state at finite tempera- tures [1].