Stephen Spender Prize 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galen's Legacy in Alexandrian Texts Written in Greek, Latin, And

chapter 3 Galen’s Legacy in Alexandrian Texts Written in Greek, Latin, and Arabic Ivan Garofalo From the end of the fifth and throughout the sixth century,1 a medical school with a philosophical framework was active in the Egyptian city of Alexandria.2 A selection was made from the available works of Galen to form a clearly de- fined curriculum for the students, divided into various courses.3 In the process of selection, Galenic works were commented on, summarised, and reduced to schemata and synopses. Subsequent decades saw a number of new studies and editions of texts connected to this tradition. This rich legacy shaped a substan- tial part of the transmission and reception of Galenic thought. The Alexandrian canon of Galenic works consists of sixteen single works or groups of works. Many Alexandrian physicians had already written com- mentaries on these works from as early as the fifth century.4 The clearest 1 The floruit of Gesios, the earliest commentator, is from around the beginning of the sixth century. John of Alexandria and Stephen are probably a generation or two later than Gesios, whom they quote. All translations into English are my own unless otherwise stated. 2 A useful presentation of the topic of this chapter is in Palmieri (2002). For textual criticism concerning the Alexandrian production, see Garofalo (2003a). For a general survey, see Duffy (1984). On late antique Alexandria, see Harris and Ruffini (2004); Pormann (2010: 419–21); Roueché (1991). For archaeological evidence, see Majcherek (2008). The professors of medi- cine who taught in Alexandria were called iatrosophistae; see Baldwin (1984). -

The Esperantist Background of René De Saussure's Work

Chapter 1 The Esperantist background of René de Saussure’s work Marc van Oostendorp Radboud University and The Meertens Institute ené de Saussure was arguably more an esperantist than a linguist – R somebody who was primarily inspired by his enthusiasm for the language of L. L. Zamenhof, and the hope he thought it presented for the world. His in- terest in general linguistics seems to have stemmed from his wish to show that the structure of Esperanto was better than that of its competitors, and thatit reflected the ways languages work in general. Saussure became involved in the Esperanto movement around 1906, appar- ently because his brother Ferdinand had asked him to participate in an inter- national Esperanto conference in Geneva; Ferdinand himself did not want to go because he did not want to become “compromised” (Künzli 2001). René be- came heavily involved in the movement, as an editor of the Internacia Scienca Re- vuo (International Science Review) and the national journal Svisa Espero (Swiss Hope), as well as a member of the Akademio de Esperanto, the Academy of Es- peranto that was and is responsible for the protection of the norms of the lan- guage. Among historians of the Esperanto movement, he is also still known as the inventor of the spesmilo, which was supposed to become an international currency among Esperantists (Garvía 2015). At the time, the interest in issues of artificial language solutions to perceived problems in international communication was more widespread in scholarly cir- cles than it is today. In the western world, German was often used as a language of e.g. -

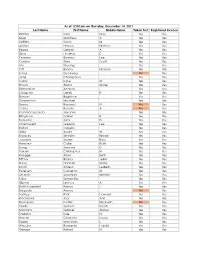

Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License

As of 12:00 am on Thursday, December 14, 2017 Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License Richter Sara May Yes Yes Silver Matthew A Yes Yes Griffiths Stacy M Yes Yes Archer Haylee Nichole Yes Yes Begay Delores A Yes Yes Gray Heather E Yes Yes Pearson Brianna Lee Yes Yes Conlon Tyler Scott Yes Yes Ma Shuang Yes Yes Ott Briana Nichole Yes Yes Liang Guopeng No Yes Jung Chang Gyo Yes Yes Carns Katie M Yes Yes Brooks Alana Marie Yes Yes Richardson Andrew Yes Yes Livingston Derek B Yes Yes Benson Brightstar Yes Yes Gowanlock Michael Yes Yes Denny Racheal N No Yes Crane Beverly A No Yes Paramo Saucedo Jovanny Yes Yes Bringham Darren R Yes Yes Torresdal Jack D Yes Yes Chenoweth Gregory Lee Yes Yes Bolton Isabella Yes Yes Miller Austin W Yes Yes Enriquez Jennifer Benise Yes Yes Jeplawy Joann Rose Yes Yes Harward Callie Ruth Yes Yes Saing Jasmine D Yes Yes Valasin Christopher N Yes Yes Roegge Alissa Beth Yes Yes Tiffany Briana Jekel Yes Yes Davis Hannah Marie Yes Yes Smith Amelia LesBeth Yes Yes Petersen Cameron M Yes Yes Chaplin Jeremiah Whittier Yes Yes Sabo Samantha Yes Yes Gipson Lindsey A Yes Yes Bath-Rosenfeld Robyn J Yes Yes Delgado Alonso No Yes Lackey Rick Howard Yes Yes Brockbank Taci Ann Yes Yes Thompson Kaitlyn Elizabeth No Yes Clarke Joshua Isaiah Yes Yes Montano Gabriel Alonzo Yes Yes England Kyle N Yes Yes Wiman Charlotte Louise Yes Yes Segay Marcinda L Yes Yes Wheeler Benjamin Harold Yes Yes George Robert N Yes Yes Wong Ann Jade Yes Yes Soder Adrienne B Yes Yes Bailey Lydia Noel Yes Yes Linner Tyler Dane Yes Yes -

Esperanto League for North America

INFORMATION CENTER ESPERANTO LEAGUE FOR NORTH AMERICA Vol.VI No.2 NEWSLETTER April 1970 RATES SET FOR JULY ESPERANTO WORKSHOP AND CONGRESS SAN FRANCISCO STATE COLLEGE William Auld, who will teach two courses in the Esperanto Workshop at San Francisco State College July 6 to 24, is a member of the Academy of Esperanto and Depute Rector of the Lornshill Academy at Alloa, Scotland. One of the most ac- complished literary and pedagogical figures in Esperanto today, he has developed a system for teaching the basics of Esperanto in 10 hours, followed by intensive practice. Class activities will include some theoret- ical and background discussion but will focus on intensive drill to develop the ability to think in Esperanto through dialogues, pattern drills, and practical person-to-person communication. The Nitty-Gritty: If you pIan to take the ele- mentary or advance course, write or wire at once for an official registration ~ to Summer Ses- sions Esperanto 195.00H, San Francisco State College, 1600 Holloway, San Francisco, Ca. 94132. 'fhere is a $5 late penalty charge for course registration after May 15. The cost of the 3-unit credit course plus student fee is $75, whether the course is taken for credit or noto (Continued on Page 2) -0- MENSA AND UNIVERSALA ESPERANTO-ASOCIO ESTABLISH TIES A link between Mensa, a world organization whose membership criterion is high intelligence, and the international Esperanto movement is being forged. (See Esperanto for February.) At the request of Victor Sadler, U.E.A. director, Mark Starr, E.I.C. chairman, presented the case for the international language at a meeting of Mensa's international directors. -

Stephen J. Davis Curriculum Vitae, P

Stephen J. Davis curriculum vitae, p. 1 STEPHEN J. DAVIS Yale University Yale University Pierson College Department of Religious Studies 261 Park Street 451 College Street New Haven, CT 06511 New Haven, CT 06511 Phone: 203-432-1298 Email: [email protected] Fax: 203-432-7844 EDUCATION: Yale University -- M.A. (1993), M.Phil. (1995), Ph.D. (1998), Religious Studies (Ancient Christianity) Dissertation: “The Cult of Saint Thecla, Apostle and Protomartyr: A Tradition of Women’s Piety in Late Antiquity” Duke University, The Divinity School -- M.Div., summa cum laude (1992) Princeton University -- A.B., English Literature (and Hellenic Studies), cum laude (1988) Senior Thesis: “Visions of History: The Poetry of W. B. Yeats and C. P. Cavafy” EMPLOYMENT HISTORY/TEACHING EXPERIENCE: Professor of Religious Studies, Yale University, New Haven, CT (2008– ) Affiliate faculty member in the Departments of History and Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, the Councils on Archaeological Studies and Middle East Studies, and the Programs in Humanities, Hellenic Studies, and Medieval Studies. Senior Research Fellow at the MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies. Associate Professor of Religious Studies, Yale University, New Haven, CT (2005–08) Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, Yale University, New Haven, CT (2002–05) Professor of New Testament and Early Church History, Evangelical Theological Seminary in Cairo (ETSC), Cairo, Egypt (1998–2002, visiting spring 2005). ETSC is the official Arabic-language seminary of the Coptic Evangelical -

Christian Missions in the Telugu Country F.P

THE TELUQU 'COUNTRY r^i 64 \ 1 I /, I :.P;0. OLit-l 5X7' CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES ITHACA. N. Y. 14853 JOHN M. OLIN LIBRARY BV 3280.T4H62 Christian missions in the Telugu country f.P 3 1924 oil 177 197 PARAGON BOOK GALLERY, LTD. "The Oriental Book Store of America" 14 East 38th Street. New York, N.Y. 10016 Tel: (212) 532-4920 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31 92401 1 1771 97 TELUGU GIRLS AT S. EBBA S, JIADRAS. CHRISTIAN MISSIONS IN THE TELUGU COUNTRY BV G. HIBBERT-WARE, M.A. Fellow of the Punjab University MISSIONARY AT KALASAPAD. TELUGU COUNTRY ILLUSTRATED PUBLISHED BY 15 TUFTON STREET, WESTMINSTER, S.W. 1912 NOTE The present volume is issued as a companion volume to the four similar books on Indian and Burmese Missions which the S.P.G. has recently published. Its object is to give a general account of all Christian Missions in the Telugu country and to give in greater detail a sketch of the particular work which the S.P.G. helps to support. The Society is greatly indebted to Mr. Hibbert-Ware for the writing of this book, which we trust may be the means of extending interest in a part of India where Christian missionary work is spreading more rapidly than in almost any other part. Mr. Hibbert-Ware, who went out to India as a missionary in 1898, is a Fellow of the Punjab University and was for some time Principal of S. -

Mauritanian Arabic. Communication and Culture Handbook. Peace Corps Language Handbook Series

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 294 423 FL 017 151 AUTHOR Hanchey, Stephen; Francis, Timothy P. TITLE Mauritanian Arabic. Communication and Culture Handbook. Peace Corps Language Handbook Series. INSTITUTION Experiment in International Living, Brattleboro, VT. SPONS AGENCY Peace Corps, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 79 NOTE 323p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Materials (For Learner) (051) LANGUAGE English; Arabic EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Arabic; Behavioral Objectives; Conversational Language Courses; Cultural Education; Daily Living Skills; Developing Nations; Foreign Countries; Grammar; *Interpersonal Communication; Introductory Courses; Proverbs; *Regional Dialects; Second Language Instruction; Social Behavior; Uncommonly Taught Languages; Vocabulary; Voluntary Agencies IDENTIFIERS *Arabic (Mauritanian); Peace Corps ABSTRACT A set of instructional materials for Mauritanian Arabic is designed for Peace Corps volunteer language instruction and geared to the daily language needs of volunteers. It consists of introductory sections on language learning in general, the languages of Mauritania, pronunciation of the Hassaniya dialect, and the textbook itself, and 30 lessons on these topics: greetings and responses, continuing a conversation, personal information, Mauritanian geography, expressions and concepts of time, shopping, foods, jobs and occupations, language learning, idioms, making tea, descriptions of residence, places and landmarks, travel, the role of the volunteer in development, development vocabulary, daily activities, description, colors, hospitality and courtesy, Islam and religious vocabulary, describing the past, school, climate and seasons, the desert, health and body parts, the tailor, housing and furnishings, and agriculture. Proverbs, a list of language behavioral objectives, and an English-Hassaniya glossary are appended. (MSE) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. -

Uys Krige and the South African Afterlife of Fernando Pessoa

Uys Krige and the South African afterlife of Fernando Pessoa Stefan Helgesson* Keywords Fernando Pessoa, Roy Campbell, Armand Guibert, Hubert Jennings, Uys Krige, Afrikaans, the world republic of letters Abstract Three letters to Hubert Jennings—two of them from the Afrikaans poet Uys Krige, one from the French poet Armand Guibert—prompt a reconsideration of the South African reception of Fernando Pessoa. Although this reception was and is clearly limited, Krige emerges here as a key individual connecting Jennings, Guibert, Roy Campbell and—by extension— Fernando Pessoa in a transnational literary network structured according to the logic of what Pascale Casonova has called “the world republic of letters” (La République Mondiale des Lettres). As such, however, this historical network has limited purchase on the contemporary concerns of South African literature. The letters alert us, thereby, not just to the inherent transnationalism of South African literature, but also to largely forgotten and, to some extent, compromised aspects of South African literary history. Palavras-chave Fernando Pessoa, Roy Campbell, Armand Guibert, Hubert Jennings, Uys Krige, Afrikaans, a república mundial das letras Resumo Três cartas a Hubert Jennings – duas delas do poeta afrikaans Uys Krige, uma do poeta francês Armand Guibert – incitam uma reconsideração da recepção de Fernando Pessoa na África do Sul. Embora essa recepção tenha sido e ainda seja claramente limitada, Krige aqui emerge como indivíduo chave a conectar Jennings, Guibert, Roy Campbell e – por extensão – Fernando Pessoa, numa rede transnacional estruturada segundo a lógica que Pascale Casanova nomeou “república mundial das letras” (La République Mondiale des Lettres). Como tal, porém, essa rede histórica tem recebido limitada atenção nas preocupações contemporâneas da literatura sul-africana. -

Khemye: Chemical Literature in Yiddish

Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 29, Number 1 (2004) 21 KHEMYE: CHEMICAL LITERATURE IN YIDDISH Stephen M. Cohen English, along with a few other languages (e.g., Ger- eastward into the Russian Empire during the 19th cen- man, French, Russian, Japanese, and Chinese), is the tury. At that time, Jews in the Russian Empire were serfs, primary vehicle for transmitting chemical knowledge peasants, or poorly educated city dwellers. They were, and discoveries today. Yet languages are not neutral car- as a rule, not educated in secular or scientific studies, riers of information; the very act of choosing a language nor even in the local official or semi-official languages for instruction implies an educational, ethnic, and per- of Russian or Polish. Universities held to strict quotas haps even a social class among the users. Given the im- for the number of Jews allowed entry per year. Those petus and the means, any language is capable of explain- few Jews who had traveled to Western Europe brought ing complex scientific phenomena. This article aims to back with them the wonders of 19th-century natural and provide a modest history of the chemical literature, con- social science and accompanying technology (1). Si- fined to the 20th century, written in a lesser-known lan- multaneously, the terrible anti-Semitism of the Russian guage, Yiddish, now considered endangered. pogroms from 1881–1897, and France’s infamous Dreyfus affair (1894) increased the nationalistic desires Yiddish’s origins, dating back about a millennium, of many Jews, culminating in Theodore Herzl’s Zionist are unclear. Linguists are still arguing over the details Congress in 1897. -

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX AARON LINDA R AARON-BRASS LORENE K AARSETH CHEYENNE M ABALOS KEN JOHN ABBOTT JOELLE N ABBOTT JUNE P ABEITA RONALD L ABERCROMBIA LORETTA G ABERLE AMANDA KAY ABERNETHY MICHAEL ROBERT ABEYTA APRIL L ABEYTA ISAAC J ABEYTA JONATHAN D ABEYTA LITA M ABLEMAN MYRA K ABOULNASR ABDELRAHMAN MH ABRAHAM YOSEF WESLEY ABRIL MARIA S ABUSAED AMBER L ACEVEDO MARIA D ACEVEDO NICOLE YNES ACEVEDO-RODRIGUEZ RAMON ACEVES GUILLERMO M ACEVES LUIS CARLOS ACEVES MONICA ACHEN JAY B ACHILLES CYNTHIA ANN ACKER CAMILLE ACKER PATRICIA A ACOSTA ALFREDO ACOSTA AMANDA D ACOSTA CLAUDIA I ACOSTA CONCEPCION 2/23/2017 1 of 271 2017 Purge List ACOSTA CYNTHIA E ACOSTA GREG AARON ACOSTA JOSE J ACOSTA LINDA C ACOSTA MARIA D ACOSTA PRISCILLA ROSAS ACOSTA RAMON ACOSTA REBECCA ACOSTA STEPHANIE GUADALUPE ACOSTA VALERIE VALDEZ ACOSTA WHITNEY RENAE ACQUAH-FRANKLIN SHAWKEY E ACUNA ANTONIO ADAME ENRIQUE ADAME MARTHA I ADAMS ANTHONY J ADAMS BENJAMIN H ADAMS BENJAMIN S ADAMS BRADLEY W ADAMS BRIAN T ADAMS DEMETRICE NICOLE ADAMS DONNA R ADAMS JOHN O ADAMS LEE H ADAMS PONTUS JOEL ADAMS STEPHANIE JO ADAMS VALORI ELIZABETH ADAMSKI DONALD J ADDARI SANDRA ADEE LAUREN SUN ADKINS NICHOLA ANTIONETTE ADKINS OSCAR ALBERTO ADOLPHO BERENICE ADOLPHO QUINLINN K 2/23/2017 2 of 271 2017 Purge List AGBULOS ERIC PINILI AGBULOS TITUS PINILI AGNEW HENRY E AGUAYO RITA AGUILAR CRYSTAL ASHLEY AGUILAR DAVID AGUILAR AGUILAR MARIA LAURA AGUILAR MICHAEL R AGUILAR RAELENE D AGUILAR ROSANNE DENE AGUILAR RUBEN F AGUILERA ALEJANDRA D AGUILERA FAUSTINO H AGUILERA GABRIEL -

A Brief History of Time - Stephen Hawking

A Brief History of Time - Stephen Hawking Chapter 1 - Our Picture of the Universe Chapter 2 - Space and Time Chapter 3 - The Expanding Universe Chapter 4 - The Uncertainty Principle Chapter 5 - Elementary Particles and the Forces of Nature Chapter 6 - Black Holes Chapter 7 - Black Holes Ain't So Black Chapter 8 - The Origin and Fate of the Universe Chapter 9 - The Arrow of Time Chapter 10 - Wormholes and Time Travel Chapter 11 - The Unification of Physics Chapter 12 - Conclusion Glossary Acknowledgments & About The Author FOREWARD I didn’t write a foreword to the original edition of A Brief History of Time. That was done by Carl Sagan. Instead, I wrote a short piece titled “Acknowledgments” in which I was advised to thank everyone. Some of the foundations that had given me support weren’t too pleased to have been mentioned, however, because it led to a great increase in applications. I don’t think anyone, my publishers, my agent, or myself, expected the book to do anything like as well as it did. It was in the London Sunday Times best-seller list for 237 weeks, longer than any other book (apparently, the Bible and Shakespeare aren’t counted). It has been translated into something like forty languages and has sold about one copy for every 750 men, women, and children in the world. As Nathan Myhrvold of Microsoft (a former post-doc of mine) remarked: I have sold more books on physics than Madonna has on sex. The success of A Brief History indicates that there is widespread interest in the big questions like: Where did we come from? And why is the universe the way it is? I have taken the opportunity to update the book and include new theoretical and observational results obtained since the book was first published (on April Fools’ Day, 1988). -

The Reign, Culture and Legacy of Ştefan Cel Mare, Voivode of Moldova: a Case Study of Ethnosymbolism in the Romanian Societies

The reign, culture and legacy of Ştefan cel Mare, voivode of Moldova: a case study of ethnosymbolism in the Romanian societies Jonathan Eagles Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD Institute of Archaeology University College London 2011 Volume 1 ABSTRACT The reign, culture and legacy of Ştefan cel Mare, voivode of Moldova: a case study of ethnosymbolism in the Romanian societies This thesis seeks to explain the nature and strength of the latter-day status of Ştefan cel Mare in the republics of Romania and Moldova, and the history of his legacy. The regime and posthumous career of Ştefan cel Mare is examined through studies of history, politics and archaeology, set within the conceptual approach to nationalism that is known as “ethnosymbolism”. At the heart of this thesis lie the questions why does Ştefan cel Mare play a key role as a national symbol and how does this work in practice? These questions are addressed within an ethnosymbolist framework, which allows for the ethnosymbolist approach itself to be subjected to a critical study. There is a lacuna in many ethnosymbolist works, a space for a more detailed consideration of the place of archaeology in the development of nationalism. This thesis contends that the results of archaeological research can be included in a rounded ethnosymbolist study. First, the history of archaeological sites and monuments may contribute to understanding the way in which historically attested cultural symbols are adopted by communities over time. Secondly, if studied carefully, archaeological evidence may have the potential to trace the evolution of identity characteristics, in line with ethnosymbolism’s attempt to account for the formation of national identity in the pre- modern era.