The Portrayal of Gender in the Feature-Length Films of Pixar Animation Studios: a Content Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doc Mcstuffins

www.usc.edu/hhs What's New Follow HH&S What a difference a year makes! We launched our new website, and supplemented that with Facebook and Twit- The Numbers ter pages, which are also new. We pioneered our StoryBus Tours, helping writers find inspiration on the streets of East Los Angeles. Farther from home, I took writers on fact-finding trips to Mumbai and South Africa—and held follow-up panel discussions at the Writers Guild of America, West (WGAW). We continued our global outreach by organizing a trip with 200 HH&S-assisted storylines Chris Keyser, president of the WGAW, and three writers and producers to the 5th International Entertainment Education Conference in Delhi, India, which was co-sponsored by Holly- events wood, Health & Society, and moderated a panel on youth en- held trepreneurship and media at the Unesco Youth Forum in Paris. Because HH&S maintains long-standing, far-reaching ties with 9 members of both the entertainment and public health com- munities—contacts that continue to grow—we remain well- positioned to continue to lead as CDC’s primary partner in the field of entertainment education. director, Hollywood, Health & Society 887links on TV/ film websites Trips to EE5, India & South Africa 600% increase in TV episodes tackling key global health topics since It was a year for stretching our HH&S outreach began in 2008 wings. In November, four writers and producers were joined by HH&S Director Sandra de Castro tipsheets on priority Buffington at the 5th Interna- health topics tion Entertainment Education Conference in Delhi, participat- 35 ing in storytelling workshops Mumbai panel discussion and panel talks. -

H K a N D C U L T F I L M N E W S

More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In H K A N D C U L T F I L M N E W S H K A N D C U LT F I L M N E W S ' S FA N B O X W E L C O M E ! HK and Cult Film News on Facebook I just wanted to welcome all of you to Hong Kong and Cult Film News. If you have any questions or comments M O N D AY, D E C E M B E R 4 , 2 0 1 7 feel free to email us at "SURGE OF POWER: REVENGE OF THE [email protected] SEQUEL" Brings Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Back to Theaters in January B L O G A R C H I V E ▼ 2017 (471) ▼ December (34) "MORTAL ENGINES" New Peter Jackson Sci-Fi Epic -- ... AND NOW THE SCREAMING STARTS -- Blu-ray Review by ... ASYLUM -- Blu-ray Review by Porfle She Demons Dance to "I Eat Cannibals" (Toto Coelo)... Presenting -- The JOHN WAYNE/ "GREEN BERETS" Lunch... Gravitas Ventures "THE BILL MURRAY EXPERIENCE"-- i... NUTCRACKER, THE MOTION PICTURE -- DVD Review by Po... John Wayne: The Crooning Cowpoke "EXTRAORDINARY MISSION" From the Writer of "The De... "MOLLY'S GAME" True High- Stakes Poker Thriller In ... Surge of Power: Revenge of the Sequel Hits Theaters "SHOCK WAVE" With Andy Lau Cinema's First Out Gay Superhero Faces His Greatest -- China’s #1 Box Offic... Challenge Hollywood Legends Face Off in a New Star-Packed Adventure Modern Vehicle Blooper in Nationwide Rollout Begins in January 2018 "SHANE" (1953) "ANNIHILATION" Sci-Fi "A must-see for fans of the TV Avengers, the Fantastic Four Thriller With Natalie and the Hulk" -- Buzzfeed Portma.. -

WORST COOKS in AMERICA: CELEBRITY EDITION Contestant Bios

Press Contact: Lauren Sklar Phone: 646-336-3745; Email: [email protected] WORST COOKS IN AMERICA: CELEBRITY EDITION Contestant Bios MINDY COHN Mindy Cohn made her acting debut as the witty, precious Eastland Academy student Natalie Green in the hit comedy series The Facts of Life. She was discovered while attending Westlake School for Girls in Bel Air, California, when actress Charlotte Rae and producer Norman Lear came to the school to authenticate scripts for their new show. Ms. Rae was so taken with the vivacious eighth grader she convinced producers to create a role for her. Mindy remained on the show for all nine seasons, also traveling to Paris and Australia with her co-stars to produce two successful television movies based on the series. Concurrently, with her role in Facts, Mindy played “Rose Jenko” in Fox’s 21 Jump Street. Other notable television appearances included Diff’rent Strokes, Double Trouble, Charles in Charge, Dream On and Suddenly Susan. In 1983, Mindy appeared in her first professional stage performance in Table Settings, written and directed by James Lapine and filmed for HBO Television. The illustrious cast included Eileen Heckart, Stockard Channing, Robert Klein, Peter Riegart, and Dinah Manoff. She went on to make her feature film debut in The Boy Who Could Fly, which co-starred Colleen Dewhurst, Fred Gwynne and Fred Savage. Mindy took a hiatus from her career to attend university, where she earned a Bachelor’s degree in Cultural Anthropology and a Masters in Education. During this time, she studied improvisation and scene work with Gary Austin and Larry Moss. -

Auto Retailing: Why the Franchise System Works Best

AUTO RETAILING: WHY THE FRANCHISE SYSTEM WORKS BEST Q Executive Summary or manufacturers and consumers alike, the automotive and communities—were much more highly motivated and franchise system is the best method for distributing and successful retailers than factory employees or contractors. F selling new cars and trucks. For consumers, new-car That’s still true today, as evidenced by some key findings franchises create intra-brand competition that lowers prices; of this study: generate extra accountability for consumers in warranty and • Today, the average dealership requires an investment of safety recall situations; and provide enormous local eco- $11.3 million, including physical facilities, land, inventory nomic benefits, from well-paying jobs to billions in local taxes. and working capital. For manufacturers, the franchise system is simply the • Nationwide, dealers have invested nearly $200 billion in most efficient and effective way to distribute and sell automo- dealership facilities. biles nationwide. Franchised dealers invest millions of dollars Annual operating costs totaled $81.5 billion in 2013, of private capital in their retail outlets to provide top sales and • an average of $4.6 million per dealership. These service experiences, allowing auto manufacturers to concen- costs include personnel, utilities, advertising and trate their capital in their core areas: designing, building and regulatory compliance. marketing vehicles. Throughout the history of the auto industry, manufactur- • The vast majority—95.6 percent—of the 17,663 ers have experimented with selling directly to consumers. In individual franchised retail automotive outlets are locally fact, in the early years of the industry, manufacturers used and privately owned. -

Suggestions for Top 100 Family Films

SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS Title Cert Released Director 101 Dalmatians U 1961 Wolfgang Reitherman; Hamilton Luske; Clyde Geronimi Bee Movie U 2008 Steve Hickner, Simon J. Smith A Bug’s Life U 1998 John Lasseter A Christmas Carol PG 2009 Robert Zemeckis Aladdin U 1993 Ron Clements, John Musker Alice in Wonderland PG 2010 Tim Burton Annie U 1981 John Huston The Aristocats U 1970 Wolfgang Reitherman Babe U 1995 Chris Noonan Baby’s Day Out PG 1994 Patrick Read Johnson Back to the Future PG 1985 Robert Zemeckis Bambi U 1942 James Algar, Samuel Armstrong Beauty and the Beast U 1991 Gary Trousdale, Kirk Wise Bedknobs and Broomsticks U 1971 Robert Stevenson Beethoven U 1992 Brian Levant Black Beauty U 1994 Caroline Thompson Bolt PG 2008 Byron Howard, Chris Williams The Borrowers U 1997 Peter Hewitt Cars PG 2006 John Lasseter, Joe Ranft Charlie and The Chocolate Factory PG 2005 Tim Burton Charlotte’s Web U 2006 Gary Winick Chicken Little U 2005 Mark Dindal Chicken Run U 2000 Peter Lord, Nick Park Chitty Chitty Bang Bang U 1968 Ken Hughes Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, PG 2005 Adam Adamson the Witch and the Wardrobe Cinderella U 1950 Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson Despicable Me U 2010 Pierre Coffin, Chris Renaud Doctor Dolittle PG 1998 Betty Thomas Dumbo U 1941 Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Norman Ferguson Edward Scissorhands PG 1990 Tim Burton Escape to Witch Mountain U 1974 John Hough ET: The Extra-Terrestrial U 1982 Steven Spielberg Activity Link: Handling Data/Collecting Data 1 ©2011 Film Education SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS CONT.. -

All Star Top Performers by Class Division: A

All Star Top Performers By Class Division: A 1101, AMHR Model Stallion, 2 & Older - Under 1 TOAD HILL'S CAPT. JACK PHAROAH, 332305, Susan Allitt-Wheeler, IL 2 MOSS GROVE THUNDER IN THE SKY, 280589, William J or Linda K Jordan or Linda D Cook, OH 2 RICHLYNN'S ROUGE HEARTBREAK KID, 303933, Lisa Kleine, IN 4 T'S HCP SPITTEN DALE, 332920, Dan or Gina Timmerman, NE 4 COCI'S SILVER LITE, 334362, Colleen Cayton, CA 6 DVM HEZA GRAND SHABODA, 334075, Nicole Pearsall & Mary Adams, PA 7 DIAMOND T'S GET YOUR SHINE ON, 334366, Amy Toliver, CA 8 LITTLE KINGS SUPER SHEIK, 310270, Mary Gray & Karen Basner, MI 9 SILVER BIRCHS EXTRAVAGANZA, 310685, Louellen & Scott Rempel, BC 10 KINGS BAY, 297155, Kay Marschel, TX 10 RHA CATCH THE WIN, 331186, Merrill or Janet Meyer, ND 10 SHF VALIANT OUTLANDER CCH, 328940, Margot E or Arthur S Spangenberg, PA 10 STRASSLEIN MARDI'S FAT TUESDAY, 335137, Chantal Brown, NM 1102, AMHR Aged Stallion, 3 & Older - 34" & Under 1 MONTY OF DREAMCATCHER, 323464, Paul & Polly Hyde, ID 2 AE RENEGADE, 311326, Holly Sager, CA 3 MAGIC MIST RENEGADE DREAM, 338035, Lori Lancaster, UT 4 MODERN CANDYMANS LEGACY, 326663, Donna Lavery, FL 5 OBSESSIVE DREAM WCF, 278928, Courtney Collins, ON 6 RHA CLASSICAL SHARIF, 305325, Linda or James Kint, PA 7 LYMRICKS WINSOR KNOT, 328983, Katelyn Peterson, WA 8 LAKEVIEWS DREAMS ON HAND, 323895, Edna or Clark or Shauna Wood, IA 9 OLIVE BRANCHS BARONS HEIR APPARENT, 330665, Gabrielle Corscadden, MT 9 LITTLE CHAPS BUCKAROO WITH A TWIST, 326694, Michelle or Joshua Fulton, CA 1103, AMHR Aged Stallion, 3 & Older Over 32" to 34" 1 MODERN CANDYMANS LEGACY, 326663, Donna Lavery, FL 1 MOSS GROVE THUNDER IN THE SKY, 280589, William J or Linda K Jordan or Linda D Cook, OH 3 ALOHA CALDWELL LOOK OF PARTNER, 329651, Shelly S. -

Becoming Legendary: Slate Financing and Hollywood Studio Partnership in Contemporary Filmmaking

Kimberly Owczarski Becoming Legendary: Slate Financing and Hollywood Studio Partnership in Contemporary Filmmaking In June 2005, Warner Bros. Pictures announced Are Marshall (2006), and Trick ‘r’ Treat (2006)2— a multi-film co-financing and co-production not a single one grossed more than $75 million agreement with Legendary Pictures, a new total worldwide at the box office. In 2007, though, company backed by $500 million in private 300 was a surprise hit at the box office and secured equity funding from corporate investors including Legendary’s footing in Hollywood (see Table 1 divisions of Bank of America and AIG.1 Slate for a breakdown of Legendary’s performance at financing, which involves an investment in a the box office). Since then, Legendary has been a specified number of studio films ranging from a partner on several high-profile Warner Bros. films mere handful to dozens of pictures, was hardly a including The Dark Knight, Inception, Watchmen, new phenomenon in Hollywood as several studios Clash of the Titans, and The Hangoverand its sequel. had these types of deals in place by 2005. But In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, the sheer size of the Legendary deal—twenty five Legendary founder Thomas Tull likened his films—was certainly ambitious for a nascent firm. company’s involvement in film production to The first film released as part of this deal wasBatman an entrepreneurial endeavor, stating: “We treat Begins (2005), a rebooting of Warner Bros.’ film each film like a start-up.”3 Tull’s equation of franchise. Although Batman Begins had a strong filmmaking with Wall Street investment is performance at the box office ($205 million in particularly apt, as each film poses the potential domestic theaters and $167 million in international for a great windfall or loss just as investing in a theaters), it was not until two years later that the new business enterprise does for stockholders. -

Into the Woods Character Descriptions

Into The Woods Character Descriptions Narrator/Mysterious Man: This role has been cast. Cinderella: Female, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: G3. A young, earnest maiden who is constantly mistreated by her stepmother and stepsisters. Jack: Male, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: B2. The feckless giant killer who is ‘almost a man.’ He is adventurous, naive, energetic, and bright-eyed. Jack’s Mother: Female, age 50 to 65. Vocal range top: Gb5. Vocal range bottom: Bb3. Browbeating and weary, Jack’s protective mother who is independent, bold, and strong-willed. The Baker: Male, age 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: Ab2. A harried and insecure baker who is simple and loving, yet protective of his family. He wants his wife to be happy and is willing to do anything to ensure her happiness but refuses to let others fight his battles. The Baker’s Wife: Female, age: 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: F3. Determined and bright woman who wishes to be a mother. She leads a simple yet satisfying life and is very low-maintenance yet proactive in her endeavors. Cinderella’s Stepmother: Female, age 40 to 50. Vocal range top: F#5. Vocal range bottom: A3. The mean-spirited, demanding stepmother of Cinderella. Florinda And Lucinda: Female, 25 to 35. Vocal range top: Ab5. Vocal range bottom: C4. Cinderella’s stepsisters who are black of heart. They follow in their mother’s footsteps of abusing Cinderella. Little Red Riding Hood: Female, age 18 to 20. -

From Snow White to Frozen

From Snow White to Frozen An evaluation of popular gender representation indicators applied to Disney’s princess films __________________________________________________ En utvärdering av populära könsrepresentations-indikatorer tillämpade på Disneys prinsessfilmer __________________________________________________ Johan Nyh __________________________________________________ Faculty: The Institution for Geography, Media and Communication __________________________________________________ Subject: Film studies __________________________________________________ Points: 15hp Master thesis __________________________________________________ Supervisor: Patrik Sjöberg __________________________________________________ Examiner: John Sundholm __________________________________________________ Date: June 25th, 2015 __________________________________________________ Serial number: __________________________________________________ Abstract Simple content analysis methods, such as the Bechdel test and measuring percentage of female talk time or characters, have seen a surge of attention from mainstream media and in social media the last couple of years. Underlying assumptions are generally shared with the gender role socialization model and consequently, an importance is stated, due to a high degree to which impressions from media shape in particular young children’s identification processes. For young girls, the Disney Princesses franchise (with Frozen included) stands out as the number one player commercially as well as in customer awareness. -

Cars Tangled Finding Nemo Wreck It Ralph Peter Pan Frozen Toy Story Monsters Inc. Snow White Alice in Wonderland the Little Merm

FRIDAY, APRIL 3RD – DISNEY DAY… AT HOME! Activity 1: • Disney Pictionary: o Put Disney movies and character names onto little pieces of paper and fold them in half o Put all of the pieces of paper into a bowl o Then draw it for their team to guess Can add a charade element to it rather than drawing if that is preferred o If there are enough people playing, you can make teams • Here are some ideas, you can print these off and cut them out or create your own list! Cars Tangled Finding Nemo Wreck It Ralph Peter Pan Frozen Toy Story Monsters Inc. Snow White Alice in Wonderland The Little Mermaid Up Brave Robin Hood Aladdin Cinderella Sleeping Beauty The Emperor’s New Groove The Jungle Book The Lion King Beauty and the Beast The Princess and the Frog 101 Dalmatians Lady and the Tramp A Bug’s Life The Fox and the Hound Mulan Tarzan The Sword and the Stone The Incredibles The Rescuers Bambi Fantasia Dumbo Pinocchio Lilo and Stitch Chicken Little Bolt Pocahontas The Hunchback of Notre Wall-E Hercules Dame Mickey Mouse Minnie Mouse Goofy Donald Duck Sully Captain Hook Ariel Ursula Maleficent FRIDAY, APRIL 3RD – DISNEY DAY… AT HOME! The Genie Simba Belle Buzz Lightyear Woody Mike Wasowski Cruella De Ville Olaf Anna Princess Jasmine Lightning McQueen Elsa Activity 2: • Disney Who Am I: o Have each family member write the name of a Disney character on a sticky note. Don’t let others see what you have written down. o Take your sticky note and put it on another family members back. -

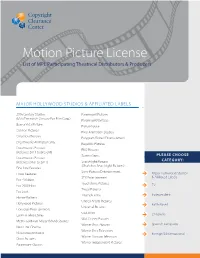

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers MAJOR HOLLYWOOD STUDIOS & AFFILIATED LABELS 20th Century Studios Paramount Pictures (f/k/a Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp.) Paramount Vantage Buena Vista Pictures Picturehouse Cannon Pictures Pixar Animation Studios Columbia Pictures Polygram Filmed Entertainment Dreamworks Animation SKG Republic Pictures Dreamworks Pictures RKO Pictures (Releases 2011 to present) Screen Gems PLEASE CHOOSE Dreamworks Pictures CATEGORY: (Releases prior to 2011) Searchlight Pictures (f/ka/a Fox Searchlight Pictures) Fine Line Features Sony Pictures Entertainment Focus Features Major Hollywood Studios STX Entertainment & Affiliated Labels Fox - Walden Touchstone Pictures Fox 2000 Films TV Tristar Pictures Fox Look Triumph Films Independent Hanna-Barbera United Artists Pictures Hollywood Pictures Faith-Based Universal Pictures Lionsgate Entertainment USA Films Lorimar Telepictures Children’s Walt Disney Pictures Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios Warner Bros. Pictures Spanish Language New Line Cinema Warner Bros. Television Nickelodeon Movies Foreign & International Warner Horizon Television Orion Pictures Warner Independent Pictures Paramount Classics TV 41 Entertaiment LLC Ditial Lifestyle Studios A&E Networks Productions DIY Netowrk Productions Abso Lutely Productions East West Documentaries Ltd Agatha Christie Productions Elle Driver Al Dakheel Inc Emporium Productions Alcon Television Endor Productions All-In-Production Gmbh Fabrik Entertainment Ambi Exclusive Acquisitions -

Your Name Here

PHENOMENAL BODIES, PHENOMENAL GIRLS: HOW YOUNG ADOLESCENT GIRLS EXPERIENCE BEING ENOUGH IN THEIR BODIES by HILARY ELIZABETH HUGHES (Under the Direction of Mark D. Vagle) ABSTRACT Drawing on philosophers (Ahmed, 2006; Fanon, 1986; Heidegger, 1927, 1962, 1992; Merleau-Ponty, 1962) and social science scholars (Dahlberg, Dahlberg, & Nystrom, 2008; Vagle, 2009, 2010, 2011; van Manen, 1990, 2000) for this phenomenological study, I asked what it was like for the seventh grade girls who participated with me in a year-long writing group to experience moments where they found themselves in bodily-not-enoughness: moments when someone or something was telling them they were not enough of something in their bodies. Using a multigenre magazine format for the dissertation, I describe how I learned—as an adult, a qualitative researcher, a middle grades teacher, and a teacher educator—from these seventh grade girls how to be-enough in my own body, by illustrating various moments when some of the girls seemed to talk-back-TO those societal messages telling them they were not pretty- enough, thin-enough, English-speaking-enough, white-enough, popular-enough, or smart-enough by embodying some kind of resistance-to those messages. I then suggest that if we as adults, qualitative researchers, middle grades educators, and teacher educators wish to try and understand better how female young adolescents of color experience living in their bodies, we should begin listening differently so that we can begin seeing/knowing/thinking the bodies of young adolescents,