Agricultural Innovation Inquiry a Submission from Farmlink

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Junee Shire Council S94a Levy Contributions Plan 2016

JUNEE SHIRE COUNCIL S94A LEVY CONTRIBUTIONS PLAN 2016 Contents Page No. PART 1 Administration and Operation of Plan 2 PART 2 Expected Development and Facilities Demand 12 Schedule l Works Schedule 14 Schedule 2 Detailed Cost Report 16 Attachment 18 Effective from: 21 June 2016 Junee Shire Council S94A Levy Contributions Plan JUNEE SHIRE COUNCIL S94A LEVY CONTRIBUTIONS PLAN 2016 PART 1 Administration and Operation 1. What is the name of this plan? This plan is called Junee Shire Council Section 94A Levy Contributions Plan 2016. 2. Date of commencement This Plan commences on 21 June 2016. 3. Purpose of this plan The purpose of this plan is: • to authorise the Council to impose, as a condition of development consent under s94A of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (“the Act”), a requirement that the applicant pay to the Council a levy determined in accordance with this plan, • to require a certifying authority (the Council or an accredited certifier) to impose, as a condition of issuing a complying development certificate, a requirement that the applicant pay to the Council a levy determined in accordance with this plan, if development consent was granted subject to a condition authorised by this plan, and • to govern the application of money paid to the Council under conditions authorised by this plan. 4. Land to which this Plan applies This Plan applies to all land within the Junee Shire local government area (LGA). 5. Development to which this Plan applies This Plan applies to development on land to which this Plan applies that requires development consent or complying development certificate under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (the Act). -

Welcome to RDA Riverinenews in This Issue: Meet the Committee

Subscribe Share Past Issues Translate Email not displaying correctly? View it in your browser. Welcome to RDA RiverinENews In this issue: Meet the Committee - James Davis TASTE Riverina 2016 Grow Our Own Western Riverina AgVision 2016 Encouraging Careers in Agriculture (NSW) Wagga Wagga to Host Agricultural Hackathon Agrihack Creating High Performance Teams RAS Foundation Rural Scholarships RDA Riverina Diary Dates 2016 What's on in the Riverina Region? Meet the Committee James Davis James Davis is the General Manager with Junee Shire Council. James has worked in Local Government for twentyfive years and in private enterprise for eight. He holds a Master in Planning, Diploma of Government Financial Services and Graduate Certificate in Local Government and has held senior leadership positions within the Riverina area. Click here to read more TASTE Riverina 2016 Well it's official ... Taste Riverina 2016 is now launched. TASTE Riverina Festival partners Riverina Regional Tourism, RDA Riverina, TAFE Riverina Institute and event operators gathered in Wagga last week to launch the TASTE Riverina 2016 program. Taste Riverina is a month long event celebrating the food diversity of the Riverina region, the growers, the producers and our food services industry! Copies of the program can be found in Visitor Information Centres or this week in The Daily Advertiser, The Area News, The Irrigator, Tumut and Adelong Times. Get your appetite on at www.tasteriverina.com.au and start planning your food odyssey for this October in the Riverina region. Click here for more information Grow Our Own Western Riverina The Grow our Own Website has been launched! The Grow Our Own Western Riverina working group are pleased to launch the Grow our Own Western Riverina website. -

New South Wales Archaeology Pty Ltd ACN 106044366 ______

New South Wales Archaeology Pty Ltd ACN 106044366 __________________________________________________________ Addendum Rye Park Wind Farm Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Assessment Report Date: November 2015 Author: Dr Julie Dibden Proponent: Rye Park Renewables Pty Ltd Local Government Area: Yass Valley, Boorowa, and Upper Lachlan Shire Councils www.nswarchaeology.com.au TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................ 1 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 4 1.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 4 2. DESCRIPTION OF THE AREA – BACKGROUND INFORMATION .............................. 7 2.1 THE PHYSICAL SETTING OR LANDSCAPE ........................................................................ 7 2.2 HISTORY OF PEOPLES LIVING ON THE LAND ................................................................ 11 2.3 MATERIAL EVIDENCE ................................................................................................... 17 2.3.1 Previous Environmental Impact Assessment ............................................................ 20 2.3.2 Predictive Model of Aboriginal Site Distribution....................................................... 25 2.3.3 Field Inspection – Methodology ............................................................................... -

CGRC-EMPLAN-2017.Pdf

Cootamundra Gundagai Regional Council Local Emergency Management Plan February 2017 Part 1 – Administration Authority The Cootamundra Gundagai Regional Council Local Emergency Management Plan (EMPLAN) has been prepared by the Cootamundra Gundagai Regional Council Local Emergency Management Committee in compliance with the State Emergency & Rescue Management Act 1989. APPROVED ……………………………………………………… Chair Cootamundra Gundagai Regional Council Local Emergency Management Committee Dated: ENDORSED ……………………………………………………… Chair South Eastern Regional Emergency Management Committee Dated: Cootamundra-Gundagai Regional Council Local Emergency Management Plan Contents Part 1 – Administration ...................................................................................................... 2 Authority ............................................................................................................................ 2 Contents ............................................................................................................................ 3 Purpose ............................................................................................................................. 4 Objectives ......................................................................................................................... 4 Scope ................................................................................................................................ 4 Principles ......................................................................................................................... -

Illabo to Stockinbingal Flood Modelling Newsletter

Illabo to Stockinbingal Floodplain modelling PROJECT UPDATE NSW About the project Guiding design and flood principles The Illabo to Stockinbingal project is a new rail corridor + flood level control – understanding any peak flood level approximately 37km in length and located within the local changes and minimising this at houses and properties and roads government areas of Junee and Cootamundra–Gundagai. This new section of rail corridor will provide a direct route + velocity control – maintaining existing velocities where from east of Illabo, tracking north to Stockinbingal and practical and understanding any changes in the speed of water exiting culverts, and providing appropriate connecting into the existing Forbes rail line. The route mitigation measures, considering existing soil conditions bypasses the steep and windy section of track called the + flow control – minimising changes to the natural flood Bethungra Spiral. flow patterns and minimising changes to existing flow control structures (contour banks) Our approach to flooding + inundation duration control – understanding the We are committed to minimising the impact of construction impact of any changes in time of inundation for land and infrastructure and operational activities on the communities in which we operate. Landowner and stakeholder input and consultation + culvert consideration – consideration of potential on existing flood conditions and potential impacts has been culvert blockage in design (Inland Rail must design for 15% blockage design factor) and will continue to be incorporated into the design of Inland Rail. + climate consideration – consideration of potential changes in flooding due to projected effects of Our guiding principles are to minimise the impacts of climate change. Inland Rail on flood behaviour for stakeholders, landowners These criteria and principles are used to ensure the project and the wider community. -

Annual Report 2015 / 2016

annual report 2015 / 2016 www.reroc.com.au annual report contents CHAIRMAN’S REPORT .................................................................................................................................................................2 SPEAKING OUT .......................................................................................................................................................................................8 WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT ................................................................................................................................ 14 BUILDING COMMUNITIES ..............................................................................................................................................19 BUILDING STRATEGIC CAPACITY .................................................................................................................... 23 MANAGING WASTE AND PROMOTING RESOURCE RECOVERY AND ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY ...............................................29 JOINT ORGANISATION PILOT .................................................................................................................................. 35 WORKING WITH OTHERS ...............................................................................................................................................37 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ..............................................................................................................................................39 MEMBERS’ DELEGATES TO REROC -

Emeritus Mayor Honour Roll

Emeritus Mayor Honour Roll 2020 Karyl Denise Knight, Greater Hume Shire 2019 Peter Laird, Carrathool Shire Council Peter Woods OAM, Concord Council Stephen Bali FCPA, F Fin, AMIIA, MP, Blacktown City Council 2018 Phillip Wells, Murrumbidgee Council 2017 Doug Eaton, Wyong Shire Council Gary Rush, Bathurst Regional Council Geoff Kettle, Goulburn Mulwaree Council Harold Johnston, Dungog Shire Council Ian Gosper, Cabonne Council Joanna Gash AM, Shoalhaven City Council Paul Joseph Hogan OAM, Greater Taree City Council Peter Abelson, Mosman Council Peter Blackmore OAM, Maitland City Council Peter Shinton, Warrumbungle Shire Council 2016 Andrew Lewis, Bourke Shire Council Angelo Pippos, Brewarrina Shire Council Angelo Tsirekas, City of Canada Bay Barry Johnston OAM, Inverell Shire Council Bill McAnally, Narromine Shire Council Brian Petschler PSM, Kiama Municipal Council Conrad Bolton, Narrabri Shire Council Gordon Bradbery OAM, Wollongong City Council Emeritus Mayor Honour Roll Jenny Clarke, Narrandera Shire Council Laurence J Henery, Jerilderie Shire Council Marianne Saliba, Shellharbour City Council Mark Troy OAM, Bellingen Shire Council Matthew Slack-Smith, Brewarrina Shire Council Michael Neville, Griffith City Council Michelle Byrne (Dr), The Hills Shire Council Ned Mannoun, Liverpool City Council Nigel Judd OAM, Temora Shire Council Norman Rex Firth Wilson OAM, Warren Shire Council Paul Lake, Campbelltown City Council Peter M Yates, Lockhart Shire Council Peter Speirs OAM, Temora Shire Council Richard Quinn, Hunter's Hill Council Ron -

The Nexus Between Water and Energy 2014-2015

The Nexus Between Water and Energy 2014-2015 THE NEXUS BETWEEN WATER AND ENERGY | i Executive Summary Central NSW Councils (Centroc) received particularly where this would benefit low In line with CEEP2 objectives the Nexus funding under the Australian socio-economic and other disadvantaged between Water and Energy Program also Government’s Community Energy communities or support energy efficiency aimed to deliver the following benefits: Efficiency Program (CEEP) Round 2 for 14 in regional and rural councils. increased embedment of energy Councils participating in the Centroc efficiency programing in Centroc Nexus between Water and Energy CEEP2 Objective 2: Demonstrate and member councils. Program. encourage the adoption of improved reduced energy costs for Centroc energy management practices within members and their communities. The purpose of this report is to provide an councils, organisations and the broader increased awareness and capability to overview of the Nexus between Water community. adopt energy efficiency practices and Energy Program (the Program), its throughout Centroc member Councils objectives, the energy efficiency The Nexus between Water and Energy and their communities. achievements and recommendations to Program’s corresponding objectives were reduced greenhouse gas emissions and the Australian Government and the to: a positive contribution to regional Centroc Board resulting from the Program 1. increase the energy efficiency of a climate adaption. delivery. range of Council assets across 14 councils by an average -

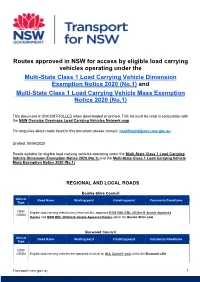

NSW Local Councils Approved OSOM Access

Routes approved in NSW for access by eligible load carrying vehicles operating under the Multi-State Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Dimension Exemption Notice 2020 (No.1) and Multi-State Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Mass Exemption Notice 2020 (No.1) This document is UNCONTROLLED when downloaded or printed. This list must be read in conjunction with the NSW Oversize Overmass Load Carrying Vehicles Network map For enquiries about roads listed in this document please contact: [email protected] Drafted: 05/06/2020 Roads suitable for eligible load carrying vehicles operating under the Multi-State Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Dimension Exemption Notice 2020 (No.1) and the Multi-State Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Mass Exemption Notice 2020 (No.1) REGIONAL AND LOCAL ROADS Bourke Shire Council Vehicle Road Name Starting point Finishing point Comments/Conditions Type NSW Eligible load carrying vehicles may travel on ALL approved NSW GML/CML 25/26m B-double Approved OSOM Routes and NSW HML 25/26m B-double Approved Routes within the Bourke Shire LGA Burwood Council Vehicle Road Name Starting point Finishing point Comments/Conditions Type NSW OSOM Eligible load carrying vehicles are approved to travel on ALL Council roads within the Burwood LGA Transport.nsw.gov.au 1 Gunnedah Shire Council Vehicle Road Name Starting point Finishing point Comments/Conditions Type NSW OSOM Eligible load carrying vehicles are approved to travel on ALL Council Roads within the Gunnedah Shire LGA Junee Shire Council Vehicle Road Name Starting point Finishing -

The Native Vegetation of Boorowa Shire

The Native Vegetation of Boorowa Shire June 2002 NSW NATIONAL PARKS AND WILDLIFE © NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, 2002. This work is copyright, however material presented in this Plan may be copied for personal use or published for educational purposes, providing that any extracts are fully acknowledged. Apart from this and any other use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced without prior written permission from NPWS. NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, 43 Bridge Street, (PO Box 1967) Hurstville NSW 2220 Tel: 02 95856444 www.npws.nsw.gov.au Cover photographs Upper: Blakelys Red Gum – Yellw Box Grassy Woodland at Godfreys Creek TSR, Lachlan Valley Way (Photographer – S. Priday) Lower: Paddock trees on the South West Slopes (Photographer – B. Wrigley) This report should be cited as follows: NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (2002) The Native Vegetation of Boorowa Shire. NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service, Hurstville NSW. Acknowledgements The NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service gratefully acknowledges the assistance of staff at Boorowa Shire Council, particularly Jody Robinson and Colin Owers. We would also like to thank the following landholders for their hospitality and for access to their properties: Alan and Jo Coles of “Currawidgee”, Steve Boyd of “Narra-Allen”, Dan and Vicki Carey of “Ballyhooley”, Judith Refshauge of “Midlands”, Tim and Dave Hewlett of “Blackburn”, Ros and Chris Daley of “Gentle Destiny”, John Anderson, Jeff Southwell of “Crystal Springs”, Doug Dockery of “Balloch”, Bruce McKenzie of “Tarengo”, Roger Clarke of “Hillrose”, Mrs Halley of “Mount Snowden”, Mr Coble of “Forestdene” and Adrian Davey of “Kurrajong”. -

2011 the Legislative Assembly for the Australian Capital

2011 THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FOR THE AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY ELECTRICITY FEED-IN (LARGE SCALE RENEWABLE ENERGY GENERATION) BILL 2011 SUPPLEMENTARY EXPLANATORY STATEMENT Presented by Simon Corbell MLA Environment and Sustainable Development 1 Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au SUPPLEMENTARY EXPLANATORY STATEMENT FOR GOVERNMENT AMENDMENTS These Government amendments are minor and technical in nature (refer to Assembly Standing Order 182A). OVERVIEW These amendments will strengthen an already important Bill and provide additional flexibility to pursue a range of renewable energy technologies and locations into the future, while allowing each release to be effectively targeted to reach optimal outcomes. AMENDMENT 1: Amendment to Clause 5 The first amendment amends clause 5(a) to change the first object of the Bill to now refer to the promotion of the establishment of large scale renewable energy generation in the Australian Capital Region (rather than ‘in and around the ACT’). This amendment provides parameters around where a large renewable energy generator can be located. AMENDMENT 2: Amendment to Clause 6(1) The second amendment amends the capacity component of the definition of a large renewable energy generator. The capacity of a large renewable energy generator will now be defined as ‘more than two hundred kilo-watts’. However, the Minister may, with each release of capacity set a higher threshold for the capacity of a large renewable energy generator’ s generating system, appropriate for each specific release. AMENDMENT 3: Amendment to Clause 10, inclusion of a new clause 10(2A) The third amendment insert a new sub-clause into clause 10 that gives the Minister the power, when releasing FiT capacity under the Bill, to state the minimum capacity of a large renewable energy generator’ s generating system for the purpose of that FiT capacity release. -

'Regional Growth' Funding Success

‘REGIONAL GROWTH’ FUNDING SUCCESS Regional Development Australia (RDA) Riverina has been successful in its bid for funding from the NSW State Government’s Regional Growth – Marketing and Promotion Fund. Partnering with seven regional councils, RDA Riverina will use the funds to support its ‘Riverina Country Change Campaign’, a program of activities designed to increase investment in the Riverina by attracting new residents and businesses. RDA Riverina Chair Diana Gibbs said the organisation is delighted with the success of the bid. “The Regional Growth – Marketing and Promotion Fund is a new $1 million program that aims to promote the benefits for businesses, investors and skilled works of setting up, investing or moving to regional NSW. “The State Government investment of almost $50,000 adds to the financial contributions of both RDA Riverina and the partnering councils to strategically market the Riverina as a place to live, work and invest.” The Riverina Country Change Campaign comprises four main activities designed to raise the profile of the Riverina: • A promotional campaign in metropolitan areas • Development of a Riverina Investment Prospectus • Updating and refreshing the Country Change website (www.countrychange.com.au) • Hosting a two-day Country Change Expo in Temora in September to showcase surrounding shires to those considering relocating from metropolitan areas. Ms Gibbs said the success of this funding bid is a real testament to the positive impact of collaboration across the region. “We thank each of the seven Riverina councils for supporting RDA Riverina in this application. I would also like to thank Temora Shire Council who worked closely with us on the application.