Northampton Past and Present, No 67 (2014)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notice of Uncontested Elections

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION West Northamptonshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for Arthingworth on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Anna Earnshaw, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Arthingworth. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) HANDY 5 Sunnybank, Kelmarsh Road, Susan Jill Arthingworth, LE16 8JX HARRIS 8 Kelmarsh Road, Arthingworth, John Market Harborough, Leics, LE16 8JZ KENNEDY Middle Cottage, Oxendon Road, Bernadette Arthingworth, LE16 8LA KENNEDY (address in West Michael Peter Northamptonshire) MORSE Lodge Farm, Desborough Rd, Kate Louise Braybrooke, Market Harborough, Leicestershire, LE16 8LF SANDERSON 2 Hall Close, Arthingworth, Market Lesley Ann Harborough, Leics, LE16 8JS Dated Thursday 8 April 2021 Anna Earnshaw Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Civic Offices, Lodge Road, Daventry, Northants, NN11 4FP NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION West Northamptonshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for Badby on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Anna Earnshaw, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Badby. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BERRY (address in West Sue Northamptonshire) CHANDLER (address in West Steve Northamptonshire) COLLINS (address in West Peter Frederick Northamptonshire) GRIFFITHS (address in West Katie Jane Northamptonshire) HIND Rosewood Cottage, Church -

Late Anglo-Saxon Finds from the Site of St Edmund's Abbey R. Gem, L. Keen

LATE ANGLO-SAXON FINDS FROM THE SITE OF ST EDMUND'S ABBEY by RICHARD GEM, M.A., PH.D., F.S.A. AND LAURENCE KEEN, M.PHIL., F.S.A., F.R.HIST.S. DURING SITE CLEARANCE of the eastern parts of the church of St Edmund's Abbey by the then Ministry of Works, followingtheir acceptance of the site into guardianship in 1955, two groups of important Anglo-Saxon material were found, but have remained unpublished until now. These comprise a series of fragments of moulded stone baluster shafts and a number of polychrome relief tiles. These are illustrated' and discussed here; it is concluded that the baluster shafts belong to around the second quarter of the 11th century or shortly thereafter; and that the tiles belong to the same period or, possibly, to the 10th century. HISTORY OF THE BUILDINGS OF ME LATE ANGLO-SAXON ABBEY The Tenth-Centwy Minster Whatever weight may be attached to the tradition that a minster was found at Boedericeswirdein the 7th century by King Sigberct, there can be little doubt that the ecclesiastical establishment there only rose to importance in the 10th century as a direct result of the translation to the royal vill of the relics of King Edmund (ob. 870);2this translation is recorded as having taken place in the reign of King Aethelstan (924 —39).3 Abbo of Fleury, writing in the late 10th century, saysthat the people of the place constructed a 'very large church of wonderful wooden plankwork' (permaxima miro ligneo tabulatu ecclesia) in which the relics were enshrined.' Nothing further is known about this building apart from this one tantalising reference. -

St Joseph's, Bedford & Our Lady's, Kempston

St Joseph’s, Bedford & Our Lady’s, Kempston Parish Priest: Canon Seamus Keenan, Assistant Priest: Fr Roy Karakkattu MSFS The Presbytery, 2 Brereton Road, Bedford, MK40 1HU, Tel: 352569 www.stjosephsbedford.org Email: [email protected] Mass Times – St Joseph’s, Bedford PALM SUNDAY Sunday 8.15am May McKenna, RIP 20th March 2016 9.30am Francis Simmonds, RIP 11.00am People of the Parish 6.30pm James Foy, RIP Monday Holy Week 10.45am Eddy Haughey& Richard Breed Tuesday Holy Week 7.30am Joan Martin, RIP 10.45am Sherin Wednesday Holy Week 7:30am King Family (Special Intention) 10.45am Bridie Tolan Thursday Maundy Thursday-Mass of the Lord’s Supper 8.00pm Ben D’Souza, RIP Friday Good Friday 3.00pm Solemn Liturgy 7.30pm Stations of the Cross HOLY WEEK Saturday Holy Saturday-Easter Vigil 8.30pm People of the Parish Today begins the most solemn week in Mass Times – Our Lady’s, Kempston the Church’s year. The great events of Sunday 9.30am Maks Gregorec, RIP Our Lord’s redemptive work are Thursday 8.00pm O’Connor Family recalled and celebrated in the liturgies Good Friday 3.00pm Solemn Liturgy of Holy Week. Please make a special 7.30pm Stations of the Cross effort to attend all the liturgies of the Sacred Triduum, beginning on Maundy Confessions: Saturday 11.30am – 12.30pm Thursday evening and in particular the St Joseph’s: 5.00pm – 5.30pm Easter Vigil on Holy Saturday at 8.30pm. Please take a separate sheet RESPONSORIAL PSALM: from the back of the church detailing the My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? times of then Holy Week services. -

Open Space Supplementary Planning Document

Open Space Supplementary Planning Document November 2011 If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format (large print, tape format or other languages) please contact us on 01832 742000. Page 2 of 25 Contents Page 1.0 Introduction 4 2.0 Purpose 4 3.0 Policy context and statutory process 4 4.0 Consultation 5 5.0 What is Open Space 5 6.0 When will open space need to be provided? 7 7.0 Calculating Provision 8 8.0 Implementing the SPD 9 Appendices: Appendix A – Glossary of Terms 10 Appendix B – Policy Context 11 Appendix C – Open Space Principles 12 Appendix D – Recommended Local Standards 15 Appendix E – A guide for the calculation of open space 17 Appendix F – Open Space requirements for Non-Residential 19 Developments Appendix G – Specification of local play types for children and young 20 people Appendix H – Flow Charts 22 Appendix I – List of Consultees 24 Page 3 of 25 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Open space can provide a number of functions: the location for play and recreation; a landscape buffer for the built environment; and provide an important habitat for biodiversity. It can also provide an attractive feature, which forms a major aspect of the character of a settlement or area. 1.2 In 2005, PMP consultants carried out an Open Space, Sport and Recreational Study of East Northamptonshire (published January 2006). In accordance with Planning Policy Guide (PPG) 17, the study identified open space and rated it on quality, quantity and accessibility issues, as well as highlighting areas of deprivation and where improvements to existing open space needed to be made. -

PASTORAL LETTER 5HUG6LED Icrnss BORDER

m PASTORAL LETTER 5HUG6LED iCRnss BORDER Mexico President Is Uncompr,omising|ARCHBiSHOP in Listening In Own Sp«W SwTk. «>d AM WRITES Occasionally some bril* Local Local liant writer picks up infor ON SOCIALISM mation from an old book, re- Edition Edition IRi^ writes it in modem Fred V. Williams of San Francisco, on Visit style and good Eng THE lish, inserts virid to Mexico, Gets Document pictures and charac ter studies, and makes it a . Rochester, N. Y.— The possibil From Prelate best seller. Willa Gather ity of winning all the peoples of New York.— (Special)— Mexi- can Catholics can look for no let admits that she took the Asia to the Catholic Church de • 4. hiding place in Jalisco and smuggled pends in great measure on the con up m the persecution that has been iu States for publication, a pastoral letter bv chief material for '‘Death version of Japan, the Most Rev. raging in that country as General __REGISTER_________________ (Name Registered in the U. S. Patent OflBce) the Most Rev. Francisco Orozco y Jiminez, Archbishop of Lazaro Cardenas takes over the Comes for the Archbishop” Boniface Sauer, O.S.B., Bishop of Ouadalajara, has just been received by The Register from from Father William H. Wonsan, Korea, declared in an in reigns of government as president. VOL X. No. S2 DENVER, COLO.. SUNDAY, DEC. 30, 1034 Cardenas has been a member of Fred V. Williams of San Francisco. Mr. Williams, who has terview with The Catholic Courier, TW O CENTS Hewlett’s well-written and here. the Revolutionary party since he just completed a trip through Mexico, brought the letter, scholarly work, “ The Life of Bishop Sauer, who stopped in was a mere boy and the philosophy which was written Nov. -

Occasional Papers from the Lindley Library © 2011

Occasional Papers from The RHS Lindley Library IBRARY L INDLEY L , RHS VOLUME FIVE MARCH 2011 Eighteenth-century Science in the Garden Cover illustration: Hill, Vegetable System, vol. 23 (1773) plate 20: Flower-de-luces, or Irises. Left, Iris tuberosa; right, Iris xiphium. Occasional Papers from the RHS Lindley Library Editor: Dr Brent Elliott Production & layout: Richard Sanford Printed copies are distributed to libraries and institutions with an interest in horticulture. Volumes are also available on the RHS website (www. rhs.org.uk/occasionalpapers). Requests for further information may be sent to the Editor at the address (Vincent Square) below, or by email ([email protected]). Access and consultation arrangements for works listed in this volume The RHS Lindley Library is the world’s leading horticultural library. The majority of the Library’s holdings are open access. However, our rarer items, including many mentioned throughout this volume, are fragile and cannot take frequent handling. The works listed here should be requested in writing, in advance, to check their availability for consultation. Items may be unavailable for various reasons, so readers should make prior appointments to consult materials from the art, rare books, archive, research and ephemera collections. It is the Library’s policy to provide or create surrogates for consultation wherever possible. We are actively seeking fundraising in support of our ongoing surrogacy, preservation and conservation programmes. For further information, or to request an appointment, please contact: RHS Lindley Library, London RHS Lindley Library, Wisley 80 Vincent Square RHS Garden Wisley London SW1P 2PE Woking GU23 6QB T: 020 7821 3050 T: 01483 212428 E: [email protected] E : [email protected] Occasional Papers from The RHS Lindley Library Volume 5, March 2011 B. -

'The Publishers of the 1723 Book of Constitutions', AQC 121 (2008)

The Publishers of the 1723 Book of Constitutions Andrew Prescott he advertisements in the issue of the London newspaper, The Evening Post, for 23 February 1723 were mostly for recently published books, including a new edition of the celebrated directory originally compiled by John Chamberlayne, Magnae Britanniae Notitia, and books offering a new cure for scurvy and advice Tfor those with consumption. Among the advertisements for new books in The Evening Post of 23 February 1723 was the following: This Day is publiſh’d, † || § The CONSTITUTIONS of the FREE- MASONS, containing the Hiſtory, Charges, Regulations, &c., of that moſt Ancient and Right Worſhipful Fraternity, for the Uſe of the Lodges. Dedicated to his Grace the Duke of Montagu the laſt Grand Maſter, by Order of his Grace the Duke of Wharton, the preſent Grand Maſter, Authoriz’d by the Grand Lodge of Maſters and War- dens at the Quarterly Communication. Ordered to be publiſh’d and recommended to the Brethren by the Grand Maſter and his Deputy. Printed for J. Senex, and J. Hooke, both over againſt St Dunſtan’s Church, Fleet-ſtreet. An advertisement in similar terms, also stating that the Constitutions had been pub- lished ‘that day’, appeared in The Post Boy of 26 February, 5 March and 12 March 1723 Volume 121, 2008 147 Andrew J. Prescott and TheLondon Journal of 9 March and 16 March 1723. The advertisement (modified to ‘just publish’d’) continued to appear in The London Journal until 13 April 1723. The publication of The Constitutions of the Free-Masons, or the Book of Constitutions as it has become generally known, was a fundamental event in the development of Grand Lodge Freemasonry, and the book remains an indispensable source for the investigation of the growth of Freemasonry in the first half of the eighteenth century. -

Mass Intentions for Fourth Sunday of Lent

St John Henry Newman Parish Our Mission Prayer by St John H. Newman GOD has created me to do Him some definite service. He has committed some work to me which He has not committed to Parish Priest: Fr Benedetto D’Autilia Phone: 01494 438300 Email: [email protected] another. I have my mission. I may never know it in this life, but I shall be told it in the next. I am a link in a chain, a bond of Deacon: Paul Priestley Email: [email protected] Mobile: 07591 462894 connection between persons. He has not created me for naught. I shall do good; I shall do His work. Glory be to the Father, Parish Secretary: Mrs Ann Masat and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit, as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, world without end. Amen Office Assistant: Mrs Maureen Mooney Safeguarding Reps: John Wiggins & Judith Forster Parish Website: www.bjhnparish.org Diocesan Notices Other Notices Newsletter email: [email protected] Deadline: 7.00pm Wednesday St Wulstan’s: HP13 7UN Our Lady of Grace: HP12 4RY Habemus Episcopum! Deo Gratias! Divine Adoration at St Augustine’s Dear Brothers and Sisters, we have a New Bishop! The Holy You are warmly invited to a beautiful evening of Eucharistic Father has appointed Canon David Oakley, a priest of the Adoration with praise and prayer ministry at St Augustine’s Church, 24 Amersham Hill, High Wycombe, HP13 6NZ. on th Archdiocese of Birmingham and currently rector of St. Mary’s 12 January 2020 Friday 17th January 2020 at 8.00pm in the Upper Room. -

Barby Parish Council Notice of Meeting

KILSBY PARISH COUNCIL NOTICE OF MEETING To members of the Council: You are hereby summoned to attend a meeting of Kilsby Parish Council to be held in Kilsby Village Hall, Rugby Road, Kilsby. Please inform your Clerk on 07581 490581 if you will not be able to attend. Members of the public and press are invited to attend a meeting of Kilsby Parish Council and to address the Council during its Public Participation session which will be allocated a maximum of 20 minutes. On……. TUESDAY 1st October, 2019 at 7.30pm In the Kilsby room of the Kilsby Village Hall, Rugby Road, Kilsby. 24th September, 2019. Please note that photographing, recording, broadcasting or transmitting the proceedings of a meeting by any means is permitted without the Council’s prior written consent so long as the meeting is not disrupted. (Openness of Local Government Bodies Regulations 2014). Please make yourself known to the Clerk. Parish Clerk: Mrs C E Valentine, 20 Styles Place, Yelvertoft, Northamptonshire,NN6 6LR ______Tel 07581 490581 e-mail [email protected]___________ 1 APOLOGIES 2 CO-OPTION to fill CASUAL VACANCIES 2.1 To note that there are two vacant seats on the Parish Council and to consider candidates who have expressed an interest in becoming a Councillor and co-opt a suitable candidate. 3 PUBLIC OPEN FORUM SESSION limited to 20 mins. 3.1 Public Open Forum Session Members of the public are invited to address the Council. The session will last for a maximum of 20 minutes with any individual contribution lasting a maximum of 3 minutes. -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

Recall of Mps

House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee Recall of MPs First Report of Session 2012–13 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 21 June 2012 HC 373 [incorporating HC 1758-i-iv, Session 2010-12] Published on 28 June 2012 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Political and Constitutional Reform Committee The Political and Constitutional Reform Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to consider political and constitutional reform. Current membership Mr Graham Allen MP (Labour, Nottingham North) (Chair) Mr Christopher Chope MP (Conservative, Christchurch) Paul Flynn MP (Labour, Newport West) Sheila Gilmore MP (Labour, Edinburgh East) Andrew Griffiths MP (Conservative, Burton) Fabian Hamilton MP (Labour, Leeds North East) Simon Hart MP (Conservative, Camarthen West and South Pembrokeshire) Tristram Hunt MP (Labour, Stoke on Trent Central) Mrs Eleanor Laing MP (Conservative, Epping Forest) Mr Andrew Turner MP (Conservative, Isle of Wight) Stephen Williams MP (Liberal Democrat, Bristol West) Powers The Committee’s powers are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in Temporary Standing Order (Political and Constitutional Reform Committee). These are available on the Internet via http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm/cmstords.htm. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the internet at www.parliament.uk/pcrc. A list of Reports of the Committee in the present Parliament is at the back of this volume. -

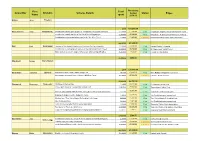

Councillor First Name Division Scheme Details Total Spent Status

First Total Remaining Councillor Division Scheme Details budget Status Payee Name spent 2009-10 Bailey John Finedon £0.00 £10,000.00 Beardsworth Sally Kingsthorpe Contribution towards play equipment - Kingsthorpe Play Builders Project £2,500.00 £7,500.00 Paid Kingsthorpe Neighbourhood Management Board Contribution towards the hire of the YMCA Bus in Kingsthorpe £1,500.00 £6,000.00 Paid Kingsthorpe Neighbourhood Management Board Contribution to design & printing costs for the 'We Were There' £100.00 £5,900.00 In progress Northamptonshire Black History Association £4,100.00 £5,900.00 Bell Paul Swanspool Opening of the Daylight Centre over Christmas for the vulnerable £1,500.00 £8,500.00 Paid Daylight Centre Fellowship Contribution to employing a p/t worker at Wellingborough Youth Project £2,800.00 £5,700.00 Paid Wellingborough Youth Project Motor skills develoment equipment for people with learning difficulties £5,250.00 £450.00 Paid Friends of Friars School £9,550.00 £450.00 Blackwell George Earls Barton £0.00 £10,000.00 Boardman Catherine Uplands New kitchen floor - West Haddon Village Hall £803.85 £9,196.15 Paid West Haddon Village Hall Committee New garage doors and locks - Lilbourne Mini Bus Garage £3,104.65 £6,091.50 In progress Lilbourne Parish Council £3,908.50 £6,091.50 Bromwich Rosemary Towcester A5 Rangers Cycling Club £759.00 £9,241.00 Paid A5 Rangers Cycling Club Cricket pitch cover for Towcestrians Cricket Club £1,845.00 £7,396.00 Paid Towcestrians Cricket Club £6,861.00 Home & away playing shirts for Towcester Ladies Hockey