Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study on Philippine Cities' Initiatives

A Case Study of Philippine Cities’ Initiatives | June – December 2017 © KCDDYangot /WWF-Philippines | Sustainable Urban Mobility — Philippine Cities’ Initiatives © IBellen / WWF-Philippines ACKNOWLEDGMENT WWF is one of the world’s largest and most experienced independent conservation organizations, with over 5 million supporters and a global network active in more than 100 countries. WWF-Philippines has been working as a national organization of the WWF network since 1997. As the 26th national organization in the network, WWF-Philippines has successfully been implementing various conservation projects to help protect some of the most biologically-significant ecosystems in Asia. Our mission is to stop, and eventually reverse the accelerating degradation of the planet’s natural environment and to build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature. The Sustainable Urban Mobility: A Case Study of Philippine Cities’ Initiatives is undertaken as part of the One Planet City Challenge (OPCC) 2017-2018 project. Project Manager: Imee S. Bellen Researcher: Karminn Cheryl Dinney Yangot WWF-Philippines acknowledges and appreciates the assistance extended to the case study by the numerous respondents and interviewees, particularly the following: Baguio City City Mayor Mauricio Domogan City Environment and Parks Management Officer, Engineer Cordelia Lacsamana City Tourism Officer, Jose Maria Rivera Department of Tourism, Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) Regional Director Marie Venus Tan Federation of Jeepney Operators and Drivers Associations—Baguio-Benguet-La Union (FEJODABBLU) Regional President Mr. Perfecto F. Itliong, Jr. Cebu City City Mayor Tomas Osmeña City Administrator, Engr. Nigel Paul Villarete City Environment and Natural Resources Officer, Ma. Nida Cabrera Cebu City BRT Project Manager, Atty. -

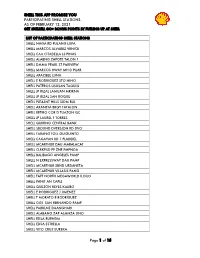

SHELL THIS APP PROMISE YOU PARTICIPATING SHELL STATIONS AS of FEBRUARY 12, 2021 Page 1 of 15

SHELL THIS APP PROMISE YOU PARTICIPATING SHELL STATIONS AS OF FEBRUARY 12, 2021 GET SHELLELL GO+ BONUS POINTS BY FUELING UP AT SHELL LIST OF PARTICIPATING SHELL STATIONS SHELL NAGA RD PULANG LUPA SHELL MARCOS ALVAREZ VENICE SHELL CAA CITADELLA LS PINAS SHELL ALABNG ZAPOTE TALON 1 SHELL DMMA PEARL ST FAIRVIEW SHELL MARCOS HWAY MH D PILAR SHELL APACIBLE LUNA SHELL E RODRIGUEZ STO NINO SHELL PATEROS USUSAN TAGUIG SHELL JP RIZAL LAMUAN MRIKNA SHELL JP RIZAL SAN ROQUE SHELL PLEASNT HILLS SJDM BUL SHELL ARANETA BRGY TATALON SHELL RETIRO COR D TUAZON QC SHELL JP LAUREL F TORRES SHELL QUIRINO CENTRAL BANK SHELL SBOUND DVERSION RD DVO SHELL TABANG TOLL GUIGUINTO SHELL CAGAYAN RD 1 PLARIDEL SHELL MCARTHUR DAU MABALACAT SHELL CLRKFILD FP ZNE PMPNGA SHELL BALIBAGO ANGELES PAMP SHELL N EXPRESSWAY DAU PAMP SHELL MCARTHUR SBND URDANETA SHELL MCARTHUR VILLASIS PANG SHELL TAFT NORTH MEGAWORLD ILOILO SHELL PANIT AN CAPIZ SHELL QUEZON REYES KALIBO SHELL E RODRIGUEZ J JIMENEZ SHELL T MORATO E RODRIGUEZ SHELL OG1 SAN FERNANDO PAMP SHELL PARKLNE DAANGHARI SHELL ALABANG ZAP ALMNZA UNO SHELL EDSA BUENDIA SHELL EDSA ESTRELLA SHELL VITO CRUZ EUREKA Page 1 of 15 SHELL THIS APP PROMISE YOU PARTICIPATING SHELL STATIONS AS OF FEBRUARY 12, 2021 SHELL SOUTH SUPER MAGALLANES SHELL QUIRINO ZAPOTE FLYOVER SHELL ALABANG ZAPOTE PAMPLONA SHELL CHINO ROCES METROPLITN SHELL EAST SERVICE RD SUCAT SHELL OSMENA HWAY ESTANISLAO SHELL JP RIZAL TRINIDAD SHELL QUIRINO NAGA RD SHELL NAT L HWAY ALABANG VIA SHELL WEST SERVICE RD CUPANG SHELL PEPSI TUNASAN SHELL NAT L HIGHWAY TUNASAN SHELL -

2018 DBP Annual Report

2 DEVELOPMENT BANK OF THE PHILIPPINES 4 DEVELOPMENT BANK OF THE PHILIPPINES As the nation marches towards progress, DBP supports the national government in achieving its agenda to power the country revved up towards sustainable economic growth. The cover presents a dynamic play for change of the bank’s corporate colors. Rays of blue and red open into a collage of infrastructure projects, depicting one of the key priorities OUR of DBP as the government’s infrastructure TRANSFORMATION bank. The historic 50-year old headquarters is prominently displayed in the design. It is a IN 2018 Made Us testament and witness to the long-term and unwavering commitment of DBP to ensure A Stronger And the country’s economic development. More Focused Development Bank Contents 1 Message from the President 20 Enduring Partnerships 69 Responsive Customer Care 2 Message to Stakeholders 34 Revitalized Governance 72 Re-invigorated Corporate Citizenship 4 Financial Highlights 36 Board of Directors 75 Audited Financial Statements 5 Milestones 48 Management Committees 82 DBP Subsidiaries 9 Revving Up The Nation 52 Senior Officers 84 DBP Products and Services 10 Purpose and Philosophy 55 Enhanced Risk Management 88 Expanded Network for 12 Delivering the Benefits 63 Re-Energized Organization Growth of Progress Artist’s Perspective of New Clark City Athletics Stadium courtesy of Bases Conversion Development Authority (BCDA) 2018 ANNUAL REPORT 1 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT My warmest greetings to the Development Bank of the Philippines (DBP) on the publication of its 2018 Annual Report. For several decades, DBP has been at the forefront of strengthening our economic growth through its array of relevant, responsive and purposeful development financing programs. -

Ready for the Road Promo

READY FOR THE ROAD PROMO LIST OF PARTICIPATING STATIONS Shell SITE NAME STATION ADDRESS SHOC+ Select deli2go SH EDSA CALOOCAN QC BOUND COSS 472 EDSA CALOOCAN CITY ✔ SH 1ST & 2ND AVE RAE CAL COSS RIZAL AVE EXT GRACE PARK CALOOCAN CITY ✔ SH KALAW DEL PILAR COSS 7 TM KALAW COR MH DEL PILAR ST ERMI MANILA CITY SH MORIONES TONDO MANILA COSS MORRIONES COR JUAN NOLASCO TONDO MANILA CITY SH LOPEZ BLVD NAVOTAS COSS 69 HONORIO LOPEZ BOULEVARD NBBS NAVOTAS CITY SH 8TH 9TH AVE B SERRANO COSS 67 8TH AND 9TH AVE B SERRANO ST CALOOCAN CITY ✔ SH J ABAD SANTOS TECSON COSS 2560 JOSE ABAD SANTOS COR TECSON TONDO MANILA CITY ✔ SH UNITED NATIONS PEREZ COSS UN AVE COR PEREZ ST PACO MANILA CITY ✔ ✔ SH JUAN LUNA DEL FIERRO COSS V DEL FIERRO ST GAGALANGIN TONDO MANILA CITY ✔ SH EDSA BANSALANGIN QC COSS 1015 EDSA COR BANSALANGIN PROJECT 7 QUEZON CITY ✔ SH 10TH AVE COR D AQUINO COSS 10TH AVE COR D AQUINO ST GRACE PARK CALOOCAN CITY SH LAONG LAAN DELA FUENTE COSS LAON LAAN COR M DELAFUENTE SAMPALOC MANILA ✔ SH ANDALUCIA REQUESENS COSS ANDALUCIA COR REQUESENS TONDO MANILA CITY ✔ SH TAYUMAN A SANTOS TONDO COSS 1205 TAYUMAN ST COR ABAD SANTOS TON MANILA CITY SH RAE COR 7TH AVE CAL DOSS 249 RIZAL AVE EXT BARANGAY 58 CALOOCAN CITY SH PASO D BLAS VALENZUELA DOSS 65 PASO DE BLAS ROAD VALENZUELA CITY SH C3 DAGAT DAGATAN CAL C 3 ROAD COR. DALAGANG BUKID ST. CALOOCAN CITY SH GOV PASCUAL POTRERO COSS 705 PASCUAL AVENUE BARANGAY POTRERO MALABON CITY ✔ SH A BONIFACIO BINUANG COSS BINUANG ST LALOMA QUEZON CITY SH MCARTHUR TINAJEROS COSS TINAJEROS POTRERO MALABON CITY ✔ SH MH DEL -

(Reapmp) in the Republic of the Philippines

No. REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS (DPWH) PREPARATORY SURVEY FOR ROAD ENHANCEMENT AND ASSET PRESERVATION MANAGEMENT PROGRAM (REAPMP) IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES FINAL REPORT OCTOBER 2009 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. EID CR(2) 09-119 COMPOSITION OF FINAL REPORT Main Report CURRENCY EXCHANGE RATE Following currency exchange rates were adopted in this report unless otherwise stipulated. (1) Philippine Peso vs. US Dollar Selling rate of Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas on June 30, 2009 USD 1= Php 48.31 (2) Philippine Peso vs. Japanese Yen Selling rate of Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas on June 30, 2009 JPY 1 = Php 0.5033 PREFACE The Government of Japan decided to conduct "The Preparatory Survey on the Project for Road Enhancement and Asset Preservation Management Program (REAPMP) in the Republic of the Philippines" and entrusted the study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA selected and dispatched a study team from March to August, 2009. The team held discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of the Philippines, and conducted field surveys at the study area. After the team returned to Japan, further studies were made. As this result, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of the Philippines for their close cooperation extended to the survey. October, 2009 TOSHIYUKI KUROYANAGI Director General Japan International Cooperation Agency Letter of Submittal Dear Sir, We are pleased to submit to you the report on“The Preparatory Survey on the Project for Road Enhancement and Asset Preservation Management Program (REAPMP) in the Republic of the Philippines”. -

Shell Stations 1 As of 11 August 2020

List of Liquid Fuel Retail Stations or LPG Dealers Implementing the 10% Tariff (EO 113) Company: PILIPINAS SHELL As of: August 11, 2020 Sites highlighted in yellow and light green have reversed diesel and gasoline pump prices effective July 31 equivalent to 1.70 per liter for both gasoline and diesel on 191 sites in CDO, Iligan, Cabadbaran, Tagbilaran, Mandaue and Anibong. ADDRESS Diesel Diesel + Gasoline Kerosene # Name of Liquid Fuel Retail Station / LPG Dealers Implementation Tariff Rate Implementation Tariff Rate Implementation Tariff Rate Implementation Tariff Rate Province City/Municipality Barangay and Street Date (Php) Date (Php) Date (Php) Date (Php) 641 SH BASAK PARDO CEBU DOSS. CEBU CEBU CITY CEBU SOUTH ROAD BASAK PARDO CEBU CITY 01/07/2020 1.70 01/07/2020 1.70 25/06/2020 1.70 642 SH PUSOK LAPU LAPU CEBU DOSS CEBU LAPU-LAPU CITY M.L QUEZON HIGHWAY, PUSOK, LAPU-LAPU CITY, CEBU 01/07/2020 1.70 01/07/2020 1.70 25/06/2020 1.70 643 SH BABAG MACTAN CEBU DOSS CEBU LAPU-LAPU CITY OLD TIANGE RD. PUROK KAPAYAS, CANJULAO, LAPU-LAPU CITY 01/07/2020 1.70 01/07/2020 1.70 25/06/2020 1.70 644 SH SAN MIGUEL CORDOVA DOSS. CEBU CORDOVA SAN MIGUEL ROAD, CORDOVA 01/07/2020 1.70 25/06/2020 1.70 645 SH LLAMAS LAWAAN TALISAY COSS CEBU TALISAY CITY CEBU SOUTH ROAD LAWAAN TALISAY CITY 01/07/2020 1.70 01/07/2020 1.70 25/06/2020 1.70 646 SH NATL HIWAY MINGLANILLA COSS. CEBU MINGLANILLA MINGLANILLA CEBU SOUTH ROAD 01/07/2020 1.70 01/07/2020 1.70 25/06/2020 1.70 647 SH UN AVE MANDAUE CEBU COSS CEBU MANDAUE CITY UNITED NATION AVENUE MANDAUE CITY CEBU 01/07/2020 1.70 01/07/2020 1.70 25/06/2020 1.70 648 SH JUAN LUNA ARCA CEBU DOSS. -

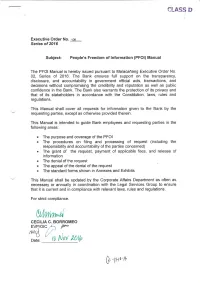

PFOI Manual Compressed.Pdf

PEOPLE’S FREEDOM OF INFORMATION MANUAL Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS i GLOSSARY ii CHAPTER 1 OVERVIEW 0101 Purpose and Coverage of the Manual 0101.1 CHAPTER 2 FILING AND PROCESSING OF REQUEST 0201 General Guidelines 0201.1 CHAPTER 3 GRANT OF THE REQUEST, PAYMENT OF APPLICABLE FEES, AND RELEASE OF INFORMATION 0301 General Guidelines 0301.1 CHAPTER 4 DENIAL OF THE REQUEST 0401 General Guidelines 0401.1 CHAPTER 5 APPEAL OF THE DENIAL OF THE REQUEST FOR INFORMATION 0501 General Guidelines 0501.1 ANNEXES Annex 2.1 List of Acceptable IDs Annex 2.2 LBP Directory Annex 2.3 Exception List Annex 2.4 PFOI Process Flow Annex 5.1 Office of Next Higher in Authority PEOPLE’S FREEDOM OF INFORMATION MANUAL Table of Contents EXHIBITS Exhibit 2.1 RRDI Exhibit 2.2 Receiving Stamp Exhibit 2.3 Memo Referral to CAD Exhibit 2.4 Letter of Denial to the Requesting Party Exhibit 2.5 Memo Referral to the Responding Unit Exhibit 2.6 Extension of Period to Respond Exhibit 2.7 Notice of Request for Extension Exhibit 3.1 Notice to Claim Exhibit 3.2 Notice of Payment of Applicable Fees Exhibit 3.3 Notice of Release of Document/Information Exhibit 4.1 Notice of Denial of Requested Information to CAD Exhibit 4.2 Notice of Denial to the Requesting Party PEOPLE’S FREEDOM OF INFORMATION MANUAL Acronyms and Abbreviations ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS AC/AD Accounting Center /Accounting Division ALU Area Legal Unit AOC Agrarian Operations Center CAD Corporate Affairs Department CCC Customer Care Center EO Executive Order PFOI People’s Freedom -

Shell Stations As of 30 June 2020

List of Liquid Fuel Retail Stations or LPG Dealers Implementing the 10% Tariff (EO 113) Company: PILIPINAS SHELL As of: June 25, 2020 ADDRESS Diesel Diesel + Gasoline Kerosene Name of Liquid Fuel Retail Station / No. LPG Dealers City/ Implementation Tariff Rate Implementation Tariff Rate Implementation Tariff Rate Implementation Tariff Rate Province Barangay and Street Municipality Date (Php) Date (Php) Date (Php) Date (Php) 1 SH 10TH AVE COR D AQUINO COSS NCR CALOOCAN CITY 10TH AVE COR D AQUINO ST GRACE PARK CALOOCAN CITY 17-Jun-20 1.62 17-Jun-20 1.62 24-Jun-20 1.58 2 SH 1ST & 2ND AVE RAE CAL COSS NCR CALOOCAN CITY RIZAL AVE EXT GRACE PARK CALOOCAN CITY 17-Jun-20 1.62 17-Jun-20 1.62 24-Jun-20 1.58 3 SH 20TH AVE PTUAZON CUBAO COSS NCR QUEZON CITY 109 20TH AVE COR P TUAZON BLVD CUBAO QUEZON CITY 17-Jun-20 1.62 17-Jun-20 1.62 24-Jun-20 1.58 4 SH 32ND ST EASTBOUND COSS NCR TAGUIG CITY 32ND ST FORT BONIFACIO GLOBAL CITY TAGUIG CITY 17-Jun-20 1.62 17-Jun-20 1.62 24-Jun-20 1.58 5 SH 4TH RD BURGOS BACOLOD COSS. NEGROS OCCIDENTAL BACOLOD CITY 4TH RD COR BURGOS ST VILLAMONTE BACOLOD CITY 17-Jun-20 1.62 17-Jun-20 1.62 24-Jun-20 1.58 6 SH 8TH 9TH AVE B SERRANO COSS. NCR CALOOCAN CITY 67 8TH AND 9TH AVE B SERRANO ST CALOOCAN CITY 17-Jun-20 1.62 17-Jun-20 1.62 24-Jun-20 1.58 7 SH A BONIFACIO BALINTAWAK COSS NCR QUEZON CITY BIGNAY ST BRGY BALINGASA BALINTAWAK QUEZON CITY 17-Jun-20 1.62 17-Jun-20 1.62 24-Jun-20 1.58 8 SH A BONIFACIO BINUANG COSS NCR QUEZON CITY BINUANG ST LALOMA QUEZON CITY 17-Jun-20 1.62 17-Jun-20 1.62 24-Jun-20 1.58 9 SH A BONIFACIO SAMONTE COSS. -

Disney Exclusives at Shell Select Participating Shell Stations As of December 09, 2020

DISNEY EXCLUSIVES AT SHELL SELECT PARTICIPATING SHELL STATIONS AS OF DECEMBER 09, 2020 LIST OF PARTICIPATING STATIONS STATION NAME SHELL EDSA KAINGIN SBOUND QC SHELL MH DEL PILAR MALABON SHELL UNITED NATIONS PEREZ SHELL A BONIFACIO BALINTAWAK SHELL EDSA BALINTAWAK QC SHELL MINDANAO COR SSS RD SHELL QUEZON AVE IBANK QC SHELL CONGRESSIONAL CULIAT SHELL POOK LIGAYA DILIMAN QC SHELL DAHLIA AVE FAIRVIEW SHELL DMMA FERIA NORTHBOUND SHELL DMMA PEARL ST FAIRVIEW SHELL CONGRESSIONAL EXT QC SHELL EDSA S TRIANGLE GMA SHELL T MORATO E RODRIGUEZ SHELL EDSA MAIN CUBAO QC SHELL KAMIAS COR KASINGKSING SHELL KALAYAAN TEACHERS VILL SHELL QUEZON AVE EDSA BOUND SHELL KALAYAAN MAKATARUNGAN SHELL 20TH AVE PTUAZON CUBAO SHELL RODRGUEZ QUEZON ANGONO SHELL MARCOS HIGHWAY DELAPAZ SHELL PARUGAN ANTIPOLO SHELL ML QUEZON SUNFLOWER SHELL KATIPUNAN 1ST IGNATIUS SHELL C5 JULIA VARGAS SHELL C5 LOGCOM NORTHBOUND SHELL C5 HERITAGE TAGUIG SHELL 32ND ST EASTBOUND SHELL C5 VALLE VERDE SHELL CAYETANO BLVD TAGUIG SHELL ORTIGAS EXT BGY ISIDRO SHELL SOUTH SUPER MAGALLANES SHELL DMA BRADCO PARANAQUE SHELL EDSA HERITAGE SHELL MACAPAGAL BELLA PQUE SHELL QUIRINO AVENUE A MABINI SHELL EDSA BARANGAY BARRANCA SHELL EDSA MALIBAY PASAY SHELL EDSA ESTRELLA SHELL ARNAIZ HARRISON SHELL OSMENA HWAY ESTANISLAO SHELL ALABANG ZAP ALMNZA UNO SHELL CAA CITADELLA LS PINAS SHELL PARKLNE DAANGHARI SHELL WEST SERVICE RD CUPANG Page 1 of 3 DISNEY EXCLUSIVES AT SHELL SELECT PARTICIPATING SHELL STATIONS AS OF DECEMBER 09, 2020 SHELL DONA SOLEDAD SM BICUTAN SHELL SUCAT STA RITA SHELL MARCOS ALVAREZ VENICE -

CHED-7 Higher Educational Institutions (HEIS) DIRECTORY 2011

Institution Name 1 ACLC-Tagbilaran 2 Advanced Institute of Technology 3 AMA Computer College-Cebu City 4 AMA Computer College-Dumaguete City 5 AMA Computer Learning Center of Mandaue 6 De La Salle Andres Soriano Memorial College 7 Asian College of Science and Technology-Dumaguete 8 Asian College of Technology 9 BIT International College - Siquijor 10 Bantayan Southern Institute 11 Baptist Theological College 12 Batuan Colleges 13 Bayawan College 14 Benedicto College 15 Blessed Trinity College 16 BMC College 17 BIT International College - Tagbilaran 18 BIT International College - Carmen 19 BIT International College - Jagna 20 BIT International College - Talibon 21 Bohol Northern Star College Inc. 22 Bohol Northwestern College 23 Bohol Wisdom School 24 Buenavista Community College 25 CBD College 26 Cebu Aeronautical Technical School 27 Cebu Doctor's University 28 Cebu Doctor's University College of Medicine 29 Cebu Eastern College 30 Cebu Institute of Medicine 31 Cebu Institute of Technology - University 32 Cebu International Distance Education College 33 Cebu International School 34 Cebu Mary Immaculate College 35 Cebu Normal University 36 Cebu Roosevelt Memorial College 37 Cebu Sacred Heart College 38 Cebu School of Midwifery 39 Cebu Technological University-Argao 40 Cebu Technological University-College of Agriculture-Sudlon/Barili 41 Cebu Technological University-College of Fisheries Technology-Carmen 42 Cebu Technological University-Daanbantayan 43 Cebu Technological University-Danao City 44 Cebu Technological University-Main 45 Cebu Technological University-Moalboal 46 Cebu Technological University-Tuburan 47 Cebu Technological University-San Francisco 48 Central Philippine Bible College 49 Bohol Island State University - Bilar 50 Bohol Island State University - Calape Polytechnic College 51 Bohol Island State University - Candijay 52 Bohol Island State University - Clarin 53 Bohol Island State University Main - Tagbilaran 54 Centre for International Education Global Colleges 55 Colegio de San Antonio de Padua 56 Colegio De Sta. -

Planes, Trains and Automobiles

Colliers Radar Philippines | Infrastructure 27 October 2016 Planes, Trains and Automobiles Impact of the Government’s Infrastructure Policy on Real Estate To improve the quality of infrastructure in the country, President Duterte ordered the streamlining of the approval process for infrastructure projects, particularly those under the public-private partnership (PPP) scheme; and ramping up of infrastructure spending equivalent to about 5% to 6% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). The implementation of infrastructure projects nationwide should provide access to properties that could be redeveloped into mixed commercial, residential, Joey Roi Bondoc hotel/leisure and industrial estates. The infrastructure Research Manager | Philippines plans of the current administration will dictate the direction of real estate developments beyond the term of [email protected] President Duterte. Consequently, we recommend that developers take advantage of the increased The daily cost of traffic congestion in the infrastructure spending by: Philippines is estimated at PHP2.4 billion . Strategic landbanking in areas outside of Metro and could go up to PHP6 billion a day by Manila as spending on infrastructure will enable decentralization from the urban core to the 2030 if infrastructure deficiency remains provinces around Metro Manila. unresolved. Expansion of mixed-use developments outside Metro Manila as these offer better value proposition than standalone developments. How the Philippines compares . Project differentiation as the market becomes Overall Infrastructure increasingly competitive and consumers are Infrastructure Country Spending as % of becoming more discerning. Ranking, 2015 GDP (2011-2014) (out of 140 countries) China 9.5 51 . Development of facilities for meetings, Vietnam 8 99 incentives, conferences, and events (MICE) and leisure in provincial hubs given the upgrading of India 7.5 74 international airports in Visayas and Mindanao. -

CSHP) DOLE-Regional Office No

REGIONAL REPORT ON THE APPROVED/CONCURRED CONSTRUCTION SAFETY & HEALTH PROGRAM (CSHP) DOLE-Regional Office No. 7 April 2018 Date No. Company Name and Address Project Name Approved JIAN ARMEL RICHARD CHRISTERSON (JARC) CONSTRUCTION AND MARINE SERVICES CONTRACT ID NO. 18HF0055 - REHABILITATION OF MULTI-PURPOSE 1 04/02/2018 CORPORATION / ABUCAYAN, BALAMBAN, BUILDING, BRGY. SAN ISIDRO, ASTURIAS, CEBU CEBU SUPREA PHILS. DEVELOPMENT CORP. / 16TH CONTRACT ID NO. 18HI0020 - PREVENTIVE MAINTENANCE OF ROAD: 2 FLR. APPLEONE EQUICOM TOWER, CEBU ASPHALT OVERLAY - SOGOD TABUELAN ROAD - K0120+954 - 04/02/2018 BUSINESS PARK, LAHUG, CEBU CITY K0121+456, SOGOD, CEBU YES CONSTRUCTION / OSMEÑA BLVD, CEBU CONTRACT ID NO. 18HI0008 - CONSTRUCTION OF CONCRETE ROAD, 3 04/02/2018 CITY BRGY. SOUTHERN POBLACION, SAN FRANCISCO, CEBU CONTRACT ID NO. 18-HE-0019 - RETROFITTING/STRENGTHENING OF QUIRANTE CONTRUCTION / N. BACALSO 4 PERMANENT BRIDGES, ABUNO BRIDGE (B00516CB) ALONG N. 04/02/2018 AVE., INAYAGAN, NAGA CITY, CEBU BACALSO AVENUE (CEBU SOUTH ROAD), CEBU PROVINCE PLD CONSTUCTION / P.C. SUICO ST., TABOK, CONTRACT ID NO. 17HN0026 - CONSTRUCTION OF 4-STOREY, 12-CL 5 04/02/2018 MANDAUE CITY SCHOOL BUILDING AT LOOK ES, LAPU-LAPU CITY CONTRACT ID NO. 18HG0065 - ORGANIZATIONAL OUTCOME 1: ENSURE SAFE AND RELIABLE NATIONAL ROAD SYSTEM, ASSET_PRESERVATION_PROGRAM;REHABILITATION/RECONSTRUCTI FIRST GRANDEUR BUILDERS / PAKIGNE, 6 ON/UPGRADING OF DAMAGED PAVED ROADS-SECONDARY ROAD- 04/02/2018 MINGLANILLA, CEBU SANTANDER-BARILI-TOLEDO ROAD;SECTION 1: K0152+628+K0152+870; SECTION 2: K0152+870+K0152+916, CEBU PROVINCE CONTRACT ID NO. 18HG0054 - LOCAL PROGRAM - LOCAL FIRST GRANDEUR BUILDERS / PAKIGNE, INFRASTRUCTURE PROGRAM; BUILDING AND OTHER STRUCTURES; 7 04/02/2018 MINGLANILLA, CEBU MULTI-PURPOSE/FACILITIES - CONSTRUCTION OF MULTI-PURPOSE BUILDING, BRGY.