Monuments to the Dead in Ancient North India∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

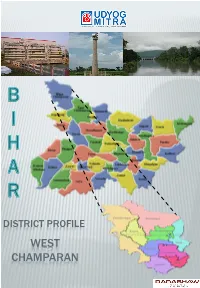

West Champaran Introduction

DISTRICT PROFILE WEST CHAMPARAN INTRODUCTION West Champaran is an administrative district in the state of Bihar. West Champaran district was carved out of old champaran district in the year 1972. It is part of Tirhut division. West Champaran is surrounded by hilly region of Nepal in the North, Gopalganj & part of East Champaran district in the south, in the east it is surrounded by East Champaran and in the west Padrauna & Deoria districts of Uttar Pradesh. The mother-tongue of this region is Bhojpuri. The district has its border with Nepal, it has an international importance. The international border is open at five blocks of the district, namely, Bagha- II, Ramnagar, Gaunaha, Mainatand & Sikta, extending from north- west corner to south–east covering a distance of 35 kms . HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The history of the district during the late medieval period and the British period is linked with the history of Bettiah Raj. The British Raj palace occupies a large area in the centre of the town. In 1910 at the request of Maharani, the palace was built after the plan of Graham's palace in Calcutta. The Court Of Wards is at present holding the property of Bettiah Raj. The rise of nationalism in Bettiah in early 20th century is intimately connected with indigo plantation. Raj Kumar Shukla, an ordinary raiyat and indigo cultivator of Champaran met Gandhiji and explained the plight of the cultivators and the atrocities of the planters on the raiyats. Gandhijii came to Champaran in 1917 and listened to the problems of the cultivators and the started the movement known as Champaran Satyagraha movement to end the oppression of the British indigo planters. -

RFP for Preparation of DPR Work Supervision of Archaeological Sites

BIHAR STATE EDUCATIONAL INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LIMITED, PATNA REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) FOR SELECTION OF CONSULTANT FOR PREPARATION OF DETAILED PROJECT REPORT (DPR) AND WORKS SUPERVISION FOR CONSERVATION, BEAUTIFICATION & DEVELOPMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES/MONUMENTS UNDER THE DEPARTMENT OF ART, CULTURE & YOUTH (DIRECTORATE OF ARCHAEOLOGY), GOVT. OF BIHAR RFP for Selection of Consultant for Preparation of DPR And Works Supervision for Conservation of Archaeological Sites in Bihar Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS S. No. Contents Page No. Disclaimer 3 Glossary 4 - 5 1 In vita tion for Proposal 6 – 8 2 Instructions to Applicants 9 - 15 A. General B. Documents 15 - 17 C. Preparation and Submission of Proposal 17 - 23 D. Evaluation Process 23 – 25 E. Appointment of Consultant 25 – 27 3 Criteria for Evaluation 27 – 29 4 Fraud and corrupt practices 29 – 30 5 Pre -Proposal Conference 30 – 31 6 Miscellaneous 31 Schedules 1 Terms of Reference 32 – 43 2 Form of Agreement 44 – 68 Annex- A 69 – 75 Annex – 1 76 Annex-2: Payment Schedule 77 Annex-3: Bank Guarantee for Performance Security 78 – 79 3 Guidance Note on Conflict of Interest 80 – 81 Appendices 1 Appendix -I: Technical Proposal 82 Form 1: Letter of Proposal 82 – 84 Form 2: Particulars of the Applicant 85 – 87 Form 3: Statement of Legal Capacity 88 Form 4: Power of Attorney 89 – 90 Form 5: Financial Capacity of Applicant 91 Form 6: Particulars of Key Personnel 92 Form 7: Proposed Methodology and Work Plan 93 Form 8: Experience of Applicant 94 Form 9: Experience of Key Personnel 95 -

West Champaran District, Bihar State

भूजल सूचना पुस्तिका पस्चचमी च륍पारण स्जला, बिहार Ground Water Information Booklet West Champaran District, Bihar State ADMINISTRATIVE MAP WEST CHAMPARAN DISTRICT, BIHAR N 0 5 10 15 20 Km Scale Masan R GAONAHA SIDHAW RAMNAGAR PIPRASI MAINATAND BAGAHA NARKATIAGANJ LAURIYA MADHUBANI SIKTA BHITAHA CHANPATTIA GandakJOGAPATTI R MANJHAULIA District Boundary BETTIAH Block Boundary THAKRAHA BAIRIA Road Railway NAUTAN River Block Headquarter के न्द्रीय भमू मजल िो셍 ड Central Ground water Board Ministry of Water Resources जल संसाधन मंत्रालय (Govt. of India) (भारि सरकार) Mid-Eastern Region Patna मध्य-पर्वू ी क्षेत्र पटना मसिंिर 2013 September 2013 1 Prepared By - Dr. Rakesh Singh, Scientist – ‘B’ 2 WEST CHAMPARAN, BIHAR S. No CONTENTS PAGE NO. 1.0 Introduction 6 - 10 1.1 Administrative details 1.2 Basin/sub-basin, Drainage 1.3 Irrigation Practices 1.4 Studies/Activities by CGWB 2.0 Climate and Rainfall 11 3.0 Geomorphology and Soils 11 - 12 4.0 Ground Water Scenario 12 – 19 4.1 Hydrogeology 4.2 Ground Water Resources 4.3 Ground Water Quality 4.4 Status of Ground Water Development 5.0 Ground Water Management Strategy 19 – 20 5.1 Ground Water Development 5.2 Water Conservation and Artificial Recharge 6.0 Ground Water related issue and problems 20 7.0 Mass Awareness and Training Activity 20 8.0 Area Notified by CGWB/SGWA 20 9.0 Recommendations 20 FIGURES 1.0 Index map of West Champaran district 2.0 Month wise rainfall plot for the district 3.0 Hydrogeological map of West Champaran district 4.0 Aquifer disposition in West Champaran 5.0 Depth to Water Level map (May 2011) 6.0 Depth to Water Level map (November 2011) 7.0 Block wise Dynamic Ground Water (GW) Resource of West Champaran district TABLES 1.0 Boundary details of West Champaran district 2.0 List of Blocks in West Champaran district 3.0 Land use pattern in West Champaran district 4.0 HNS locations of West Champaran 5.0 Blockwise Dynamic Ground Water Resource of West Champaran District (2008-09) 6.0 Exploration data of West Champaran 7.0 Chemical parameters of ground water in West Champaran 3 WEST CHAMPARAN - AT A GLANCE 1. -

Total Syllabus, AIH & Archaeoalogy, Lucknow University

Department of Ancient Indian History and Archaeology, University of Lucknow, Lucknow B.A. Part - I Paper I : Political History of Ancient India (from c 600 BC to c 320 AD) Unit I 1. Sources of Ancient Indian history. 2. Political condition of northern India in sixth century BC- Sixteen mahajanapadas and ten republican states. 3. Achaemenian invasion of India. 4. Rise of Magadha-The Bimbisarids and the Saisunaga dynasty. 5. Alexander’s invasion of India and its impact. Unit II 1. The Nanda dynasty 2. The Maurya dynasty-origin, Chandragupta, Bindusara 3. The Maurya dynasty-Asoka: Sources of study, conquest and extent of empire, policy of dhamma. 4. The Maurya dynasty- Successors of Asoka, Mauryan Administration. The causes of the downfall of the dynasty. Unit III 1. The Sunga dynasty. 2. The Kanva dynasty. 3. King Kharavela of Kalinga. 4. The Satavahana dynasty. 1 Unit IV 1. The Indo Greeks. 2. The Saka-Palhavas. 3. The Kushanas. 4. Northern India after the Kushanas. PAPER– II: Social, Economic & Religious Life in Ancient India UNIT- I 1. General survey of the origin and development of Varna and Jati 2. Scheme of the Ashramas 3. Purusharthas UNIT- II 1. Marriage 2. Position of women 3. Salient features of Gurukul system- University of Nalanda UNIT- III 1. Agriculture with special reference to the Vedic Age 2. Ownership of Land 3. Guild Organisation 4. Trade and Commerce with special reference to the 6th century B.C., Saka – Satavahana period and Gupta period UNIT- IV 1. Indus religion 2. Vedic religion 3. Life and teachings of Mahavira 4. -

Annual Report 2018-19

Annual Report 2018-19 NATIONAL CULTURE FUND ANNUAL REPORT 2018-19 NATIONAL CULTURE FUND Annual Report 2018-19 NATIONAL CULTURE FUND ANNUAL REPORT AND AUDITED ACCOUNTS 2018-19 NATIONAL CULTURE FUND Annual Report 2018-19 P R E F A C E During the year 2018-19, National Culture Fund (NCF) has unrelentingly continued its thrust on re-framing & revitalizing its ongoing projects and striven towards their completion. Not only has it established new partnerships, but has also taken steps forwards towards finalizing the existing partnerships in a holistic way. Year on Year the activities and actions of NCF have grown owing to the awareness as well as necessity to preserve and protect India's rich culture and heritage. The relentless efforts of NCF in the year 2018-19 for being instrumental in preserving and conserving the heritage are being recorded in this Annual Report. NCF also ensures accountability and credibility for being a brand image for the Government, corporate sector and civil society. The field of heritage conservation and development of the art and culture is vast and important and NCF will continue to develop and make a positive contribution to the field in the years to come. NATIONAL CULTURE FUND Annual Report 2018-19 NATIONAL CULTURE FUND Annual Report 2018-19 CONTENTS S.No. Details Page No. 1. INTRODUCTION TO NATIONAL CULTURE FUND 6 2. OBJECTIVES OF NATIONAL CULTURE FUND 8 3. MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATION 9 4. STRUCTURE OF THE NATIONAL CULTURE FUND 9-11 5. HIGHLIGHTS OF 2018-19 12 i projects completed in 2018-19 12 ii new initiatives in 2018-19 18 6. -

Sources to Reconstruct the Age of the Mauryas

Assignment 11 Class IX History Chapter - 5 The Mauryan Empire Note: ● The Study Material consists of 3 parts - ○ Part I - The important highlights of the chapter. ○ Part II - The activity based on the chapter. ○ Part III - The questions based on the study material you need to answer in your respective notebook and submit when you are back to the school. SOURCES TO RECONSTRUCT THE AGE OF THE MAURYAS There are many sources that reconstruct the age of the Mauryas. Literary Sources Among the literary sources, mention may be made of Indica, written by Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to Pataliputra. From his book we get a lot of information about Mauryan administration and life of the people. The book Arthshastra is attributed to Kautilya or Chanakya. It provides details of the art of administration, society and economy in the age of the Mauryas. The Vayu Purana and Matsya Purana give a list of rulers of different dynasties, Mauryas being one of them. Vishakadatta's Mudrarakshasa is considered to be the best historical drama in the whole of Sanskrit literature. It throws light on the position of the Nandas and the activities of Chandragupta Maurya and Chanakya. It also gives us an idea of the social life of people in those days. Archaeological Sources The Rock Edicts of Ashoka-are the most reliable sources of information for Ashoka's rule. Ashoka in Rock Edict XII prescribes the following rules to be followed: (i) Non-violence abstention from killing of living beings, (ii) Truthfulness, (iii) Obedience to parents and elders, and (iv) Respect towards teachers. -

History of Buddhism and Jainism Upto 1000 A.D

Syllabus M.A. Part - II Paper - VII : (Option B) History of Buddhism and Jainism upto 1000 A.D. 1. Sources (Buddhism) a) Canonical and Non-Canonical Pali Literature b) Art and Architecture. 2. The Buddha Life of Buddha (from Birth till the Mahaparinirvana). 3. Teachings of Buddha a) Four Noble Truths. Eight fold path b) Law of Dependent Origination. (Paticcaccsamuccapada) c) Origin and Development of Sangha and Vinaya. 4. Buddhism and its Expansion a) Three Buddhist Councils b) Dhamma messengers sent by Asoka (Ashoka) after 3rd Buddhist Council, c) Buddhist Sects. 5. Impact of Buddhism on Society. a) Epistemological and Logical Aspects of Buddhism. 6. Sources (Jainism) Agamas - Literature of Jaina. Art and Architecture. 7. The Mahavira. Life of Mahavira. 8. Teachings of Mahavira a) Ethics b) NineTattvas c) Anekaravada • d) Six Dravyas 9. Spread of Jainism. a) Three Jaina councils b) King Samprati‘s contribution. c) Major Jain Sects 10. Impact of Jainism on Society 1 SOURCES OF BUDDHISM : (LITERARY SOURCES) Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Importance of Various Sources 1.3 Literary Sources Canonical Pali Literature 1.4 Non-Canonical Pali Literature 1.5 How Authentic is Pali -Literature ? 1.6 Summary 1.7 Suggested Readings 1.8 Unit End Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES (A) By reading this material student will understand which sources should be utilized for getting the information about Ancient Indian History and Culture & History of Buddhism itself. (B) Student will understand importance of the original literary sources known as ‗BUDDHA VACANA‘(Words of the Buddha) and its allied literature as a chief source for deriving information pertaining to history and culture. -

The Translation of Buddhism in the Funeral Architecture of Medieval China

religions Article The Translation of Buddhism in the Funeral Architecture of Medieval China Shuishan Yu School of Architecture, Northeastern University, Boston, MA 02115, USA; [email protected] Abstract: This article explores the Buddhist ritual and architectural conventions that were incor- porated into the Chinese funeral architecture during the medieval period from the 3rd to the 13th centuries. A careful observation of some key types of sacred architectural forms from ancient East Asia, for instance, pagoda, lingtai, and hunping, reviews fundamental similarities in their form and structure. Applying translation theory rather than the influence and Sinicization model to analyze the impact of Buddhism on Chinese funeral architecture, this article offers a comparative study of the historical contexts from which certain architectural types and imageries were produced. It argues that there was an intertwined mutual translation of formal and ritual conventions between Buddhist and Chinese funeral architecture, which had played a significant role in the formations of both architectural traditions in Medieval China. Keywords: Buddhist architecture; funeral architecture; Chinese architecture; pagoda; lingtai; xiang- tang; mubiao; hunping; mingqi; mingtang 1. Introduction Since its legendary introduction to the imperial court during the Eastern Han dynasty Citation: Yu, Shuishan. 2021. The 1 Translation of Buddhism in the (25–221 CE), Buddhism had a profound impact on every aspect of the Chinese civiliza- 2 Funeral Architecture of Medieval -

Mirror on Bettiah Raj & Wildlife

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR INNOVATIVE RESEARCH IN MULTIDISCIPLINARY FIELD ISSN – 2455-0620 Volume - 2, Issue - 11, Nov - 2016 MIRROR ON BETTIAH RAJ & WILDLIFE: A PLACE TO VISIT Sanjiv Kumar Sharma Assistant Professor, School of Hospitality and Tourism Management SRM University, Sikkim, India Email: [email protected] Abstract: The Diwani Bettiah Raj held the largest territory under its jurisdiction. It consisted of all of Champaran except for a small portion held by the Ram Nagar Raj (also held by Bhumihars). Bettiah Raj also came into being as a result of mallikana chaudharai, the connection with the revenue administration building on local dominance and the capability of controlling and protecting hundreds of villages. Internal disputes and family quarrels divided the Raj in course of time. The last zamindar was Harendra Kishore Singh, who was born in 1854 and succeeded his father, Rajendra Kishore Singh in 1883. In 1884, he received the title of Maharaja Bahadur as a personal distinction and a Khilat and a send from the Lieutenant Governor of Bengal, Sir Augustus Rivers Thompson. He was created a Knight Commander of the Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire on 1 March 1889. He was appointed a member of the Legislative Council of Bengal in January 1891. He was also a member of The Asiatic Society He was the last ruler of Bettiah Raj. West Champaran District was carved out of the old Champaran District in the year 1972 as a result of re-organization of the District in the state. It was formerly a subdivision of Saran District and then Champaran District with its Headquarters as Bettiah. -

Ancient and Medieval Nepal

@ 1st Edition, 1960 D. R. Regmi, Kathmandu, Nepal. Published by K. L. MUKHOPADHYAY, 61 1 A, Banchharam Akrur Lane, Calcutta 12. India. Price : Rs. 15.00 Printed by R. Chatterjee, at the Bhani Printers Private Ltd., 38, Strand Road, Calcutta-1. m The Shrine of Pasupatinath from the western gate Jalasayana Vishnu ( 7th Century A. D. ) CONTENTS kist of Abbreviations Bibliography Map Foreword . Preface to the First Edition . Preface to the Second Edition . CHAPTERI1 : GENERAL OBSERVATIONS ON SOME ASPECTS OF NEPALESE LIFE AND CULTURE The Antiquity of the Newars of Kathmandu . Kiatas in Ancient History . Their first entry into the Nepal Valley . The Kiratas and the Newars . First Settlement in the Valley . Why they were called Newars . The Newars and the Lichhavis . The Newars of Kathmandu . Origin . Religion . Newari Festivals . Customs and Manners . Caste System . Occupation. Language and Cultural Achievements Relation with India . Art and Architecture in Nepal . The Stupas . Swayambhunath and Bauddha . The Temples . The Nepal Style . Sculpture . Painting . Gift to Asia . Modern Art . ANCIENT NEPAL EARLY NEPAL Sources . The Dawn ... The Kirata Dynasty . The Pre-Kirata Period . The Kirata Rulers 4 ... The Lichhavi Dynasty . / . The So-called Lichhavi Character of Nepal Constitution Genealogy & Chronology . Inscriptions . The Date of Manadeva . The Era of the Earlier Inscriptions . The Epoch Year of the First Series of Inscriptions . Facts of History as Cited by Manadeva's Changu Inscription . Chronology Recitified . Manadeva's Successors . The Ahir Guptas . Religion in Early Nepal . CHAPTERIV : GUPTA SUCCESSORS The Tibetan Era of 595 A.D. TheEpochof the Era . The Epoch year of the Era . Amsuvarman's Documents . -

Satyagraha-In-Champaran.Pdf

SATYAGRAHA IN CHAMPARAN BY RAJENDRAPRASAD NAVAJIVAN PUBLISHING HOUSE AHMEDABAD Second Revised Edition, September, 1949 : 3,000 Copies Two Rupees Four Annas Printed ana jruoupaed Jivanji Dahyabhai JJesai, rjy' Navajivan Press, italupur, Ahmedabad PUBLISHERS' NOTE After his return to India from South Africa in 1914 Gandhiji tried his method of Satyagraha on what may be called a mass scale for the first time in Champaran. How he was led to take up the cause of the oppressed Champaran ryot and how as a result was compelled to civilly defy a police order for the first time on Indian soil has been graphically describ- ed by him in l\is Autobiography. About the Cham- " paran Satyagraha he however wrote : To give a full account of the Champaran enquiry would be to nar- rate the history, for the period, of the Champaran ryot, which is out of the question in these chapters. The Champaran enquiry was a bold experiment with truth and ahimsa. For the details the reader must turn to Sjt. Rajendraprasad's history of the Cham- paran Satyagraha." The Champaran experiment forms a vital chap- ter in the development of the Satyagraha method in India. It is no exaggeration to say that to all stu- dents of Gandhiji's method of social and political work a knowledge of the detailed history of the experiment is indispensable. It is certainly lucky for the future students of Satyagraha that a man of the intellectual eminence of Dr. Rajendraprasad was one of the batch of the Bihar lawyers who joined Gandhiji in his campaign. -

The Mauryan Age(322BC-184BC)

Magadh Mahila college, Patna University Department of History Bhawana singh (Guest Faculty) Email id- [email protected] Mobile Number-7909027756 Unit -5 , B.A. 1st year The Mauryan Age(322BC-184BC) The establishment of Mauryan empire was a turning point in the history of Indian territory. The control of this massive empire continued for over a long period of almost 140years over of large part of northern India. After the overthrow of the Nanda Dynasty at Magadh the Mauryas came to prominence. The empire came into being when Chandragupta Maurya stepped into the vaccum created by the departure of Alexander of Macedonia from the western borders of India. In his rise to power, he was aided and counseled by his chief minister Kautilya, who wrote the Arthashastra, a compendium of kingship and governance. Sources of Mauryan Empire: The history of their rule is rendered comparatively reliable on account of evidence obtained from a variety of sources. There are three types of sources available about the Mauryan Empire. Literary Source: Brahmanical Literature: 1. Arthashastra of Kutilya/Chanakya/Vishnugupta; It is a detailed work on statecraft. Kautilya‟s work consist of 15 volumes(Adhikarnas). The first five deals with internal administration (tantra), the next eight with inter-state relations (avapa), and the last two with miscellaneous topics. 2. Indica of Megasthense: This book was based on his travels and experience in India. The book has not survived but fragments are preserved in later Greek and Latin works, the earliest and most important of which are those of Diodorus, Strabo, Arrian, Pliny. 3.