Vigna (Leguminosae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) James Andrew Lackey Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1977 A synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) James Andrew Lackey Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Lackey, James Andrew, "A synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) " (1977). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 5832. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/5832 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Dipogon Lignosus (L.) Verde, DOLICHOS PEA, AUSTRALIAN PEA

Dipogon lignosus (L.) Verde, DOLICHOS PEA, AUSTRALIAN PEA. Perennial herbaceous vine, somewhat twining, sprawling and climbing over itself and other plants; shoots in range ± strigose, glaucous. Stems: strongly ridged aging cylindric, to 3 mm diameter, with 3 or 5 ridges descending from each leaf (at least 2 from stipules), tough, flexible, green-striped, sparsely strigose with downward-pointing hairs, glaucous with wax persistent at nodes. Leaves: helically alternate, pinnately 3-foliolate, with terminal leaflet on rachis, petiolate with pulvinus, with stipules; stipules 2, attached to stem at nodes, triangular-ovate with bulbous base, 4−5 mm long, on young leaf typically spreading, with colorless margins, acute at tip, parallel-veined, upper surface glabrous, lower surface and margins strigose with upward-pointing hairs, ± persistent; petiole 37−55 mm long, pulvinus conspicuously swollen, 2−5 mm long, sparsely strigose, glaucous, above deeply channeled, sparsely strigose with mostly upward-pointing hairs, glaucous; stipels 1 subtending each lateral leaflet and 2 subtending terminal leaflet, linear-lanceolate, 1.8−3 mm long, short-ciliate on curved margin (sometimes purple), glaucous; petiolule = pulvinus and as long as stipel, sparsely short-strigose; rachis deeply channeled, 10−20 mm long, glaucous, sparsely short-hairy; blades of leaflets rhombic-ovate to ovate, lateral leaflets asymmetric, 16−57 × 10−37 mm, terminal leaflet symmetric, 20−60 × 12−45 mm, rounded to broadly tapered at base, entire and strigose short-ciliate on margins, acute to acuminate at tip, conspicuously 3-veined at base with principal veins raised on both surfaces to midblade, glabrous but sparsely strigose along principal veins, lower surface conspicuously gray-glaucous. -

Evolution of Angiosperm Pollen. 7. Nitrogen-Fixing Clade1

Evolution of Angiosperm Pollen. 7. Nitrogen-Fixing Clade1 Authors: Jiang, Wei, He, Hua-Jie, Lu, Lu, Burgess, Kevin S., Wang, Hong, et. al. Source: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 104(2) : 171-229 Published By: Missouri Botanical Garden Press URL: https://doi.org/10.3417/2019337 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non - commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/Annals-of-the-Missouri-Botanical-Garden on 01 Apr 2020 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by Kunming Institute of Botany, CAS Volume 104 Annals Number 2 of the R 2019 Missouri Botanical Garden EVOLUTION OF ANGIOSPERM Wei Jiang,2,3,7 Hua-Jie He,4,7 Lu Lu,2,5 POLLEN. 7. NITROGEN-FIXING Kevin S. Burgess,6 Hong Wang,2* and 2,4 CLADE1 De-Zhu Li * ABSTRACT Nitrogen-fixing symbiosis in root nodules is known in only 10 families, which are distributed among a clade of four orders and delimited as the nitrogen-fixing clade. -

Fabaceae) Subfam

J. Jpn. Bot. 92(1): 34–43 (2017) Harashuteria, a New Genus of Leguminosae (Fabaceae) Subfam. Papilionoideae Tribe Phaseoleae a a b, Kazuaki OHASHI , Koji NATA and Hiroyoshi OHASHI * aSchool of Pharmacy, Iwate Medical University, Yahaba, Iwate, 028-3694 JAPAN; bHerbarium TUS, Botanical Garden, Tohoku University, Sendai, 980-0862 JAPAN *Corresponding author: [email protected] (Accepted on November 25, 2016) A new genus, Harashuteria K. Ohashi & H. Ohashi, is proposed as a member of the tribe Phaseoleae of Leguminosae (Fabaceae) based on Shuteria hirsuta Baker by comparative morphological observation and molecular phylogenetic analysis of Shuteria and its related genera. Molecular phylogenetic analysis was performed using cpDNA (trnK/matK, trnL–trnF and rpl2 intron) markers. Our molecular phylogeny shows that Shuteria hirsuta is sister to Cologania and is distinct from Shuteria vestita or Amphicarpaea, although the species has been attributed to these genera. A new combination, Harashuteria hirsuta (Baker) K. Ohashi & H. Ohashi is proposed. Key words: Amphicarpaea, Cologania, Fabaceae, Glycininae, Harashuteria, Hiroshi Hara, new genus, Phaseoleae, Shuteria, Shuteria hirsuta. The genus Shuteria Wight & Arn. was protologue. Kurz (1877) recognized Shuteria established on the basis of S. vestita Wight & hirsuta as a member of Pueraria, because he Arn. including 4–5 species in Asia (Schrire described Pueraria anabaptista Kurz citing 2005). The genus belongs to the subtribe S. hirsuta as its synonym (hence Pueraria Glycininae in the tribe Phaseoleae and is anabaptista is superfluous). Amphicarpaea closely allied to Amphicarpaea, Cologania, lineata Chun & T. C. Chen is adopted as a and Dumasia especially in the flower structures correct species by Sa and Gilbert (2010) in the (Lackey 1981). -

Fruits and Seeds of Genera in the Subfamily Faboideae (Fabaceae)

Fruits and Seeds of United States Department of Genera in the Subfamily Agriculture Agricultural Faboideae (Fabaceae) Research Service Technical Bulletin Number 1890 Volume I December 2003 United States Department of Agriculture Fruits and Seeds of Agricultural Research Genera in the Subfamily Service Technical Bulletin Faboideae (Fabaceae) Number 1890 Volume I Joseph H. Kirkbride, Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L. Weitzman Fruits of A, Centrolobium paraense E.L.R. Tulasne. B, Laburnum anagyroides F.K. Medikus. C, Adesmia boronoides J.D. Hooker. D, Hippocrepis comosa, C. Linnaeus. E, Campylotropis macrocarpa (A.A. von Bunge) A. Rehder. F, Mucuna urens (C. Linnaeus) F.K. Medikus. G, Phaseolus polystachios (C. Linnaeus) N.L. Britton, E.E. Stern, & F. Poggenburg. H, Medicago orbicularis (C. Linnaeus) B. Bartalini. I, Riedeliella graciliflora H.A.T. Harms. J, Medicago arabica (C. Linnaeus) W. Hudson. Kirkbride is a research botanist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory, BARC West Room 304, Building 011A, Beltsville, MD, 20705-2350 (email = [email protected]). Gunn is a botanist (retired) from Brevard, NC (email = [email protected]). Weitzman is a botanist with the Smithsonian Institution, Department of Botany, Washington, DC. Abstract Kirkbride, Joseph H., Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L radicle junction, Crotalarieae, cuticle, Cytiseae, Weitzman. 2003. Fruits and seeds of genera in the subfamily Dalbergieae, Daleeae, dehiscence, DELTA, Desmodieae, Faboideae (Fabaceae). U. S. Department of Agriculture, Dipteryxeae, distribution, embryo, embryonic axis, en- Technical Bulletin No. 1890, 1,212 pp. docarp, endosperm, epicarp, epicotyl, Euchresteae, Fabeae, fracture line, follicle, funiculus, Galegeae, Genisteae, Technical identification of fruits and seeds of the economi- gynophore, halo, Hedysareae, hilar groove, hilar groove cally important legume plant family (Fabaceae or lips, hilum, Hypocalypteae, hypocotyl, indehiscent, Leguminosae) is often required of U.S. -

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY BIBLIOGRAPHY Ackerfield, J., and J. Wen. 2002. A morphometric analysis of Hedera L. (the ivy genus, Araliaceae) and its taxonomic implications. Adansonia 24: 197-212. Adams, P. 1961. Observations on the Sagittaria subulata complex. Rhodora 63: 247-265. Adams, R.M. II, and W.J. Dress. 1982. Nodding Lilium species of eastern North America (Liliaceae). Baileya 21: 165-188. Adams, R.P. 1986. Geographic variation in Juniperus silicicola and J. virginiana of the Southeastern United States: multivariant analyses of morphology and terpenoids. Taxon 35: 31-75. ------. 1995. Revisionary study of Caribbean species of Juniperus (Cupressaceae). Phytologia 78: 134-150. ------, and T. Demeke. 1993. Systematic relationships in Juniperus based on random amplified polymorphic DNAs (RAPDs). Taxon 42: 553-571. Adams, W.P. 1957. A revision of the genus Ascyrum (Hypericaceae). Rhodora 59: 73-95. ------. 1962. Studies in the Guttiferae. I. A synopsis of Hypericum section Myriandra. Contr. Gray Herbarium Harv. 182: 1-51. ------, and N.K.B. Robson. 1961. A re-evaluation of the generic status of Ascyrum and Crookea (Guttiferae). Rhodora 63: 10-16. Adams, W.P. 1973. Clusiaceae of the southeastern United States. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 89: 62-71. Adler, L. 1999. Polygonum perfoliatum (mile-a-minute weed). Chinquapin 7: 4. Aedo, C., J.J. Aldasoro, and C. Navarro. 1998. Taxonomic revision of Geranium sections Batrachioidea and Divaricata (Geraniaceae). Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 85: 594-630. Affolter, J.M. 1985. A monograph of the genus Lilaeopsis (Umbelliferae). Systematic Bot. Monographs 6. Ahles, H.E., and A.E. -

Angiosperm Ovules: Diversity, Development, Evolution

Annals of Botany 107: 1465–1489, 2011 doi:10.1093/aob/mcr120, available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org INVITED REVIEW: PART OF A SPECIAL ISSUE ON EVOLUTION AND DEVELOPMENT Angiosperm ovules: diversity, development, evolution Peter K. Endress* Institute of Systematic Botany, University of Zurich, Zollikerstrasse 107, 8008 Zurich, Switzerland * E-mail [email protected] Received: 2 March 2011 Returned for revision: 29 March 2011 Accepted: 11 April 2011 Published electronically: 23 May 2011 † Background Ovules as developmental precursors of seeds are organs of central importance in angiosperm Downloaded from flowers and can be traced back in evolution to the earliest seed plants. Angiosperm ovules are diverse in their position in the ovary, nucellus thickness, number and thickness of integuments, degree and direction of curvature, and histological differentiations. There is a large body of literature on this diversity, and various views on its evolution have been proposed over the course of time. Most recently evo–devo studies have been concentrated on molecular developmental genetics in ovules of model plants. † Scope The present review provides a synthetic treatment of several aspects of the sporophytic part of ovule http://aob.oxfordjournals.org/ diversity, development and evolution, based on extensive research on the vast original literature and on experi- ence from my own comparative studies in a broad range of angiosperm clades. † Conclusions In angiosperms the presence of an outer integument appears to be instrumental for ovule curvature, as indicated from studies on ovule diversity through the major clades of angiosperms, molecular developmental genetics in model species, abnormal ovules in a broad range of angiosperms, and comparison with gymnosperms with curved ovules. -

Monographs of Invasive Plants in Europe: Carpobrotus Josefina G

Monographs of invasive plants in Europe: Carpobrotus Josefina G. Campoy, Alicia T. R. Acosta, Laurence Affre, R Barreiro, Giuseppe Brundu, Elise Buisson, L Gonzalez, Margarita Lema, Ana Novoa, R Retuerto, et al. To cite this version: Josefina G. Campoy, Alicia T. R. Acosta, Laurence Affre, R Barreiro, Giuseppe Brundu, etal.. Monographs of invasive plants in Europe: Carpobrotus. Botany Letters, Taylor & Francis, 2018, 165 (3-4), pp.440-475. 10.1080/23818107.2018.1487884. hal-01927850 HAL Id: hal-01927850 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01927850 Submitted on 11 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ARTICLE Monographs of invasive plants in Europe: Carpobrotus Josefina G. Campoy a, Alicia T. R. Acostab, Laurence Affrec, Rodolfo Barreirod, Giuseppe Brundue, Elise Buissonf, Luís Gonzálezg, Margarita Lemaa, Ana Novoah,i,j, Rubén Retuerto a, Sergio R. Roiload and Jaime Fagúndez d aDepartment of Functional Biology, Area of Ecology, Faculty of Biology, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain; bDipartimento -

Consolidated List of Environmental Weeds in New Zealand

Consolidated list of environmental weeds in New Zealand Clayson Howell DOC RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT SERIES 292 Published by Science & Technical Publishing Department of Conservation PO Box 10420, The Terrace Wellington 6143, New Zealand DOC Research & Development Series is a published record of scientific research carried out, or advice given, by Department of Conservation staff or external contractors funded by DOC. It comprises reports and short communications that are peer-reviewed. Individual contributions to the series are first released on the departmental website in pdf form. Hardcopy is printed, bound, and distributed at regular intervals. Titles are also listed in our catalogue on the website, refer www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Science & technical. © Copyright May 2008, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 1176–8886 (hardcopy) ISSN 1177–9306 (web PDF) ISBN 978–0–478–14412–3 (hardcopy) ISBN 978–0–478–14413–0 (web PDF) This report was prepared for publication by Science & Technical Publishing; editing by Sue Hallas and layout by Lynette Clelland. Publication was approved by the Chief Scientist (Research, Development & Improvement Division), Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. When printing, recycled paper is used wherever possible. CONTENTS Abstract 5 1. Introduction 6 2. Environmental weed lists 7 2.1 Weeds in national parks and reserves 1983 7 2.2 Problem weeds in protected natural areas 1990 7 2.3 Problem weeds in forest and scrub reserves 1991 8 2.4 Weeds in protected natural areas 1995 8 2.5 Ecological weeds on conservation land 1996 9 2.6 DOC weeds 2002 9 2.7 Additional lists 9 2.7.1 Weeds on Raoul Island 1996 9 2.7.2 Problem weeds on New Zealand islands 1997 9 2.7.3 Ecological weeds on DOC-managed land 1997 10 2.7.4 Weeds affecting threatened plants 1998 10 2.7.5 ‘Weed manager’ 2000 10 2.7.6 South Island wilding conifers 2001 10 3. -

Rbcl and Legume Phylogeny, with Particular Reference to Phaseoleae, Millettieae, and Allies Tadashi Kajita; Hiroyoshi Ohashi; Yoichi Tateishi; C

rbcL and Legume Phylogeny, with Particular Reference to Phaseoleae, Millettieae, and Allies Tadashi Kajita; Hiroyoshi Ohashi; Yoichi Tateishi; C. Donovan Bailey; Jeff J. Doyle Systematic Botany, Vol. 26, No. 3. (Jul. - Sep., 2001), pp. 515-536. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0363-6445%28200107%2F09%2926%3A3%3C515%3ARALPWP%3E2.0.CO%3B2-C Systematic Botany is currently published by American Society of Plant Taxonomists. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/aspt.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. -

C,,'I't CC.Mólo.) -- Cfx)15~ E.,..Z.,J6.(T T

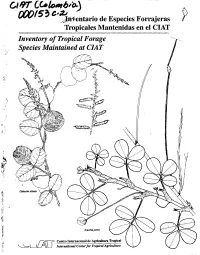

C,,'I'T CC.MÓlo.) -- CfX)15~ e.,..z.,J6.(T t . dE· F . /;;~... en arIo especIes orraJeras Tropicales Mantenidas en el CIAT Inventory ofTropical Forage Species·Maintained at CIAT J , Gslactia strists \L'~tlf' Arachis pintoi n "'I? Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical ~U~U Internalional Cenler lor Tropkal Agrkulture 58 J/1 :7 ·7(/11 Inventario de Especies Forrajeras r) Tropicales Mantenidas en el CIAT Inventory o/ Tropical Forage Species Maintained at CIAT Alba Marina Torres G. Javier Belalcázar G. Brigitte L. Maass Rainer Schultze-Kraft 13'¡5~i 3 O NOV. '~93 Documento de Trabajo No. 125 Working Document No. 125 r¡==:>c:J fM"l7 Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical ~DL.I'\\U InternaJional Center for Tropical Agriculture Contenido Página Introducción 1 Estado Actual de la Colección de Leguminosas y Gramíneas 2 Organización 2 Guía para Usar el Inventario 3 Referencias 12 Especialistas Consultados para la Identificación de Algunos Géneros 13 Especies de Germoplasma de Forrajes Tropicales 16 Fuente Bibliográfica 34 Contents Page Introduction 7 Current Status of (he Legurne and Grass Collection 8 Organization 8 Guide to Using the Inventory 9 References 12 Specialists Consulted for Identification of Sorne Genera 13 Tropical Forage Species Germplasrn 16 Bibliographic Source 34 III INVENTARIO DE ESPECIES FORRAJERAS TROPICALES MANTENIDAS EN EL CIAT Alba Marina Torres G. ' Javier Belalcázar G. ' Brigitte L. Maass2 Rainer Schultze-Krafr' Introducción El banco de germoplasma de especies tropicales con potencial forrajero mantenidas en el Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT) se inici6 en 1971 ante la necesidad de obtener materiales, especialmente de leguminosas, para el mejoramiento de las pasturas. -

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS Instituto De Biologia

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS Instituto de Biologia TIAGO PEREIRA RIBEIRO DA GLORIA COMO A VARIAÇÃO NO NÚMERO CROMOSSÔMICO PODE INDICAR RELAÇÕES EVOLUTIVAS ENTRE A CAATINGA, O CERRADO E A MATA ATLÂNTICA? CAMPINAS 2020 TIAGO PEREIRA RIBEIRO DA GLORIA COMO A VARIAÇÃO NO NÚMERO CROMOSSÔMICO PODE INDICAR RELAÇÕES EVOLUTIVAS ENTRE A CAATINGA, O CERRADO E A MATA ATLÂNTICA? Dissertação apresentada ao Instituto de Biologia da Universidade Estadual de Campinas como parte dos requisitos exigidos para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Biologia Vegetal. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Fernando Roberto Martins ESTE ARQUIVO DIGITAL CORRESPONDE À VERSÃO FINAL DA DISSERTAÇÃO/TESE DEFENDIDA PELO ALUNO TIAGO PEREIRA RIBEIRO DA GLORIA E ORIENTADA PELO PROF. DR. FERNANDO ROBERTO MARTINS. CAMPINAS 2020 Ficha catalográfica Universidade Estadual de Campinas Biblioteca do Instituto de Biologia Mara Janaina de Oliveira - CRB 8/6972 Gloria, Tiago Pereira Ribeiro da, 1988- G514c GloComo a variação no número cromossômico pode indicar relações evolutivas entre a Caatinga, o Cerrado e a Mata Atlântica? / Tiago Pereira Ribeiro da Gloria. – Campinas, SP : [s.n.], 2020. GloOrientador: Fernando Roberto Martins. GloDissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Biologia. Glo1. Evolução. 2. Florestas secas. 3. Florestas tropicais. 4. Poliploide. 5. Ploidia. I. Martins, Fernando Roberto, 1949-. II. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Instituto de Biologia. III. Título. Informações para Biblioteca Digital Título em outro idioma: How can chromosome number