IN RE: Proposed Amendment of Kentucky Rules of Evidence (KRE)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Guide

Research Guide FINDING CASES I. HOW TO FIND A CASE WHEN YOU KNOW THE CITATION A. DECIPHERING LEGAL CITATIONS 1. CASE CITATIONS A case citation includes: the names of the parties, the volume number of the case reporter, the abbreviated name of the reporter, the page number where the case can be found, and the year of the decision. EXAMPLE: Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta, 30 Cal.3d 800 (1982). Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta = names of the parties 30 = volume number of the case reporter Cal. = abbreviated name of the case reporter, California Reports 3d = series number of the case reporter, California Reports 800 = page number of the case reporter (1982) = year of the decision 2. ABBREVIATIONS OF REPORTER NAMES The abbreviations used in citations can be deciphered by consulting: a. Prince’s Bieber Dictionary of Legal Abbreviations, 6th ed. (Ref. KF 246 .p74 2009) b. Black's Law Dictionary (Ref. KF 156 .B624 2009). This legal dictionary contains a table of abbreviations. Copies of Black's are located on dictionary stands throughout the library, as well as in the Reference Collection. 3. REPORTERS AND PARALLEL CITATIONS A case may be published in more than one reporter. Parallel citations indicate the different reporters publishing the same case. EXAMPLE: Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta, 30 Cal.3d 800, 180 Cal. Rptr. 628, 640 P.2d 764 (1982). 02/08/12 (Rev.) RG14 (OVER) This case will be found in three places: the "official" California Reports 3d (30 Cal. 3rd 800); and the two "unofficial" West reporters: the California Reporter (180 Cal. -

Australian Guide to Legal Citation, Third Edition

AUSTRALIAN GUIDE TO LEGAL AUSTRALIAN CITATION AUST GUIDE TO LEGAL CITA AUSTRALIAN GUIDE TO TO LEGAL CITATION AUSTRALIAN GUIDE TO LEGALA CITUSTRATION ALIAN Third Edition GUIDE TO LEGAL CITATION AGLC3 - Front Cover 4 (MJ) - CS4.indd 1 21/04/2010 12:32:24 PM AUSTRALIAN GUIDE TO LEGAL CITATION Third Edition Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc in collaboration with Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc Melbourne 2010 Published and distributed by the Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc in collaboration with the Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Australian guide to legal citation / Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc., Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc. 3rd ed. ISBN 9780646527390 (pbk.). Bibliography. Includes index. Citation of legal authorities - Australia - Handbooks, manuals, etc. Melbourne University Law Review Association Melbourne Journal of International Law 808.06634 First edition 1998 Second edition 2002 Third edition 2010 Reprinted 2010, 2011 (with minor corrections), 2012 (with minor corrections) Published by: Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc Reg No A0017345F · ABN 21 447 204 764 Melbourne University Law Review Telephone: (+61 3) 8344 6593 Melbourne Law School Facsimile: (+61 3) 9347 8087 The University of Melbourne Email: <[email protected]> Victoria 3010 Australia Internet: <http://www.law.unimelb.edu.au/mulr> Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc Reg No A0046334D · ABN 86 930 725 641 Melbourne Journal of International Law Telephone: (+61 3) 8344 7913 Melbourne Law School Facsimile: (+61 3) 8344 9774 The University of Melbourne Email: <[email protected]> Victoria 3010 Australia Internet: <http://www.law.unimelb.edu.au/mjil> © 2010 Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc and Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc. -

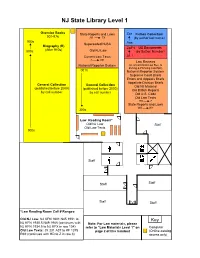

NJ State Library Level 1

NJ State Library Level 1 Oversize Books State Reports and Laws Zzz Fiction Collection 001-976 AK TX (by author last name) 900s Superseded NJSA Aaa Biography (B) Zp/P4 US Documents (After 910s) 800s Old NJ Law (by SuDoc Number) Current Law Texts A1.1 A KE Law Reviews National Reporter System (U. of Cincinnati Law Rev. to Zoning & Planning Law Rpt.) 001s National Reporter System Supreme Court Briefs Errors and Appeals Briefs Appellate Division Briefs General Collection General Collection Old NJ Material (published before 2000) (published before 2000) Old British Reports by call number by call number Old U.S. Code Old Law Texts HD Z State Reports and Laws WA WY 300s Law Reading Room* Old NJ Law Staff Old Law Texts 300s Staff Staff Staff Staff Staff *Law Reading Room Call # Ranges: Old NJ Law: NJ KFN 1801 N45 1981 to Key NJ KFN 1930.5 N49 1988 (continues with Note: For Law materials, please NJ KFN 1934.5 to NJ KFX in row 104) refer to “Law Materials Level 1” on Computer Old Law Texts: JX 231 A37 to KF 1375 page 2 of this handout (Online-catalog R69 (continues with HD to Z in row 3) access only) Law Materials Level 1 Title Row Title Row Alabama Reports and Session Laws 107 NJ Forms Legal and Business 11 Alaska Reports and Session Laws 107 NJ Law Journal 119 Alcoholic Beverage Control 12 NJ Law Reports 10 American Digest 99 NJ Law Times Reporter 10 American Jurisprudence 99 NJ Laws 11 Arizona Reports and Session Laws 107 NJ Legislative Index 11 Arkansas Reports and Session Laws 107, 108 NJ Misc. -

Abandoning Law Reports for Official Digital Case Law Peter W

Cornell Law Library Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository Cornell Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship Spring 2011 Abandoning Law Reports for Official Digital Case Law Peter W. Martin Cornell Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub Part of the Courts Commons, Legal Writing and Research Commons, and the Science and Technology Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Peter W., "Abandoning Law Reports for Official Digital Case Law" (2011). Cornell Law Faculty Publications. Paper 1197. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub/1197 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE JOURNAL OF APPELLATE PRACTICE AND PROCESS ARTICLES ABANDONING LAW REPORTS FOR OFFICIAL DIGITAL CASE LAW* Peter W. Martin** I. INTRODUCTION Like most states Arkansas entered the twentieth century with the responsibility for case law publication imposed by law on a public official lodged within the judicial branch. The "reporter's" office was then, as it is still today, a "constitutional" one.' Title and role reach all the way back to Arkansas's * Q Peter W. Martin, 2011. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 543 Howard Street, 5th Floor, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. -

How to Locate a Case Using a Digest

Sacramento County Public Law Library 609 9th St. Sacramento, CA 95814 saclaw.org (916) 874-6012 >> Home >> Law 101 DIGESTS How to Locate a Case Using a Digest The Law Library has two sets of West Digests in print format (now published by Thomson Reuters): Table of Contents The United States Supreme Court Digest, used to locate 1. How to Locate a Case Using United States Supreme Court cases, is located in Compact Topic and Key Number System in Shelving next to the Supreme Court Reporter, at KF 101 .1 Westlaw ...................................... 2 U55. Like all digests, each volume in the set is updated 2. Abbreviations and Locations of with pocket parts. Case Reporters ............................ 4 West’s California Digest, located in Row C-9 of Compact Shelving at KFC 57 .W47, is used to locate California Supreme Court and California Appellate Court cases. Digests are arranged alphabetically by topic. Examples of the approximately 400 topics are: Banks and Banking, Franchises, Insurance, Libel and Slander, Partnership, Fraud, and Criminal Law. Each topic is divided into subtopics known as "key numbers." A complete list of topic headings is available in the front of each digest volume. A complete list of key numbers is available at the beginning of each topic. A Quick Reference Guide to West Key Number System is available online west.thomson.com/documentation/westlaw/wlawdoc/wlres/keynmb06.pdf. Locate a topic and key number that interests you by scanning the list of topic headings and key numbers or by using the Descriptive Word Index at the end of each set of digests. -

Loislaw Case Coverage Federal Reporters

Loislaw Case Coverage Loislaw includes comprehensive coverage of cases and associated citations for the reporters and date ranges listed here (except as noted for the F. Supp and B.R. reporters) and select coverage of cases and associated citations for unofficial reporters not listed here or reporters outside of the date ranges we cover. Jurisdiction Court Reporter Citation Style Date Range Volumes Status Federal Reporters U.S. U.S. Supreme Court U.S. Reports U.S. 1754-present 1-present Official Supreme Court Reporter S.Ct. 1935-present 55-present Unofficial U.S. 1st Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F 3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F 2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 6th Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 7th Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. -

Public Libraries Legal Research Toolkit for Kentucky

Public Libraries Legal Research Toolkit for Kentucky Presented by the American Association of Law Libraries Legal Information Services to the Public Special Interest Section (AALL LISP-SIS) Compiled by Marcus Walker, Law School Archivist/Digital Collections Librarian, University of Louisville Brandeis School of Law Library Legislative Branch State Statutes Official printed versions are Baldwin’s Kentucky Revised Statutes (published by Thomson Reuters) and Michie’s Kentucky Revised Statutes (published by LexisNexis). The online version is available at the Legislative Research Commission website: https://legislature.ky.gov/Law/Statutes/Pages/default.aspx. State Constitution The Kentucky Constitution can be found in either of the official versions of the Kentucky Revised Statutes. Michie’s (LexisNexis) has the constitution contained within Volume 1, while Baldwin’s (Thomson Reuters) spreads it out over Volumes 1, 2, and 2A. An online version can be found at the Legislative Research Commission website: https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/constitution. The page is divided into topics. Click on a topic for a summary for each constitutional article. Click the summary to read the full text of the article as a PDF. State Session Laws If you are seeking acts passed within a current session, the Secretary of State maintains a database of enacted legislation that is updated almost immediately after approval. Go to https://www.sos.ky.gov/admin/Executive/legislation/Pages/default.aspx, and click the database link. At the end of each session, the Legislative Research Commission produces bound volumes of the Kentucky Acts with the legislation arranged in chronological order. An online version is available at https://legislature.ky.gov/Law/Pages/KyActs.aspx. -

California Style Manual

CALIFORNIA STYLE MANUAL Fourth Edition A HANDBOOK OF LEGAL STYLE FOR CALIFORNIA COURTS AND LAWYERS By Edward W. Jessen Reporter of Decisions for the Supreme Court and Courts of Appeal .W4-23370-9 ©1942, 1961, 1977, 1986,2000 by the Supreme Court of California Page composition by Imagelnk, San Francisco Cover design by Side by Side Designs, San Francisco Editiorial preparation and manufacturing West Group, California's Official Legal Publisher FOREWORD For almost 60 years, the legal community of California has benefited from the publication of the California Style Manual. The manual provides a guide to standard legal style in the appellate courts, and benefits litigants and jurists alike by establishing a common stylistic base that permits read- ers to focus readily on substance rather than form. In the 14 years since publication of the third edition of the Style Manual, much has changed in the processes used for creating legal docu- ments. A personal computer on the desk is now the rule rather than the exception for most lawyers and judges. At the same time, the availability of diverse reference resources has expanded the ease and scope of research. This latest revision of the manual reflects and responds to many of the changes that the legal profession has experienced, while maintaining a steady hold on the practices that have served the courts and the profession so well. I extend my appreciation to the Reporter of Decisions and those who have assisted him in the task of revising this valuable reference tool. Ronald M. George Chief Justice of California iii SUPREME COURT APPROVAL To the Reporter of Decisions: Pursuant to the authority conferred on the Supreme Court of Cali- fornia by Government Code section 68902, the California Style Manual, Fourth Edition, as submitted to this court for review is approved and adopted as the official organ for the styles to be used in the publication of the Official Reports. -

Abbreviations / Abr ´Eviations

ABBREVIATIONS / ABREVIATIONS´ The following is a list of abbreviations used in this publication. It includes unions, courts, boards, tribunals, law reports and general abbreviations requiring explanation. Unless the plural is set out in the list, it is formed by adding ‘s’ to the abbreviation given. Voici une liste des abr´eviations etant´ utilis´ees dans cette publication. Cette liste comporte des abr´eviations des syndicats, des tribunaux judiciaires et administratifs, des commis- sions, des recueils de jurisprudence ainsi que des abr´eviations d’ordre plus g´en´eral devant etreˆ expliqu´ees. En l’absence d’indications contraires, le pluriel de ces abr´eviations est constitu´ee par l’ajout d’un ‘s’ a` l’abr´eviation. [ ] A Atlantic Reporter ABMGB Alberta Municipal Government Board A. • Abbott A.B.P.P.U.M. / ABPPUM Association des bib- • Adolphus & Ellis, Queen’s Bench lioth´ecaires et des professeurs de l’Universit´e de Moncton • Alberta ABSRB Alberta Surface Rights Board • American [ ] A.C. Law Reports, Appeal Cases • American and English Annotated Cases A.C. • Arrˆet´e en conseil • Louisiana Annuals • Assembl´ee consultative (U.N.) A.A.C.M. / AACM Association des avocats de la Couronne du Manitoba A.C.A.C. / ACAC Air Crew Association Canada A.A.F.C. / AAFC Association des artisans du film A.C.A.C. No. Cour dappel de la Cour Martiale Du canadien Canada A.A.H.P. / AAHP Association of Allied Health Pro- A.C.C.T.A. / ACCTA Association canadienne du fessionals: Newfoundland and Labrador contrˆole du trafic a´erien A.A.H.P.O. -

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW LIBRARY GOLDING MEDIA CENTER List of Microform Holdings Cumulative to Fall-Winter, 2014-2015***

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW LIBRARY GOLDING MEDIA CENTER List of Microform Holdings Cumulative to Fall-Winter, 2014-2015*** ABA Journal. January 1988 – May, 2014. 60 ALI-ABA (American Law Institute -American Bar Association) 98 CLE Review, v. 5-32, 1974-2006. ALI-ABA Committee on Continuing Professional Education, v. 16 8 9 ALI:Annual Report of the Director,15th-76th Meeting,1937-1999. 85 ALI Proceedings:v.1-23; 1923-1998. & Publications. 85 Rest. of the Law, Agency 0010.-1250. Rest. of the Law, Business Association 0020.-0450. Rest. of the Law, 2ndConflict of Laws 0010.-2970. Rest. of the Law, Contracts 0010.-2075. Rest. of the Law, Foreign Relations Law of the U.S. 0010.0410 Rest. of the Law, Judgements 0010.-0530. Rest. of the 3rd, Governing Lawyers.0100.-0510. Rest. of the Law, Property 0004.-3170. Restatement, 2nd Property 3180.-3600. Restatement, 3rd Property:Mortgages,6000.-6450. Rest. of the Law, Restitution 0010.-0540. Rest. of the Law, Sales of Land 0010.-0066. Rest. of 3rd,Suretyship & Guaranty,0010.-0500. Rest. of the Law, Security 0010.-0581. Rest. of the Law, Torts 0010.-2450 Rest. of the Law, 2nd Torts 2460.- 3709. Rest. Of the Law, 3rd Torts P.L. 4100-5230 Rest. of the Law, Trusts 0010.1500. Rest. Of the Law, 3rd Trusts...2405 Restatement in the Courts 0010.-0210. Restatement Third Unfair Competition. 0010.-0500. A Model Land Development Code 0002.-0370. Administration of Criminal Law 0060.-0090. Law of Air flight 0010.-0100. Code of Criminal Procedure 0004.-0500. Code of Evidence 0006.-0290. -

Australian Guide to Legal Citation V4

4 Australian Guide to Legal Citation Fourth Edition USTRALIAN UIDE A G TO LEGAL CITATION Fourth Edition Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc in collaboration with Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc Melbourne 2018 Published and distributed by the Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc in collaboration with the Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Australian Guide to Legal Citation / Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc., Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc. 4th ed. ISBN 9780646976389. Bibliography. Includes index. Citation of legal authorities - Australia - Handbooks, manuals, etc. 808.06634 First edition 1998 Second edition 2002 Third edition 2010, 2011 (with minor corrections), 2012 (with minor corrections) Published by: Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc Reg No A0017345F · ABN 21 447 204 764 Melbourne University Law Review Telephone: (+61 3) 8344 6593 Melbourne Law School Facsimile: (+61 3) 9347 8087 The University of Melbourne Email: <[email protected]> Victoria 3010 Australia Website: <http://www.mulr.unimelb.edu.au> Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc Reg No A0046334D · ABN 86 930 725 641 Melbourne Journal of International Law Telephone: (+61 3) 8344 7913 Melbourne Law School Facsimile: (+61 3) 8344 9774 The University of Melbourne Email: <[email protected]> Victoria 3010 Australia Website: <http://www.mjil.unimelb.edu.au> © 2018 Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc and Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc. This work is protected by the laws of copyright. Except for any uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) or equivalent overseas legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced, in any manner or in any medium, without the written permission of the publisher. -

Too Broke to Hire an Attorney - How to Conduct Basic Legal Research in a Law Library

Digital Commons at St. Mary's University Faculty Articles School of Law Faculty Scholarship 2006 Too Broke to Hire an Attorney - How to Conduct Basic Legal Research in a Law Library Mike Martinez Jr St. Mary's University School of Law, [email protected] Michael P. Forrest Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/facarticles Part of the Legal Writing and Research Commons Recommended Citation Michael P. Forrest and Mike Martinez, Jr., Too Broke to Hire an Attorney - How to Conduct Basic Legal Research in a Law Library, 9 Scholar 67 (2006). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOO BROKE TO HIRE AN ATTORNEY? HOW TO CONDUCT BASIC LEGAL RESEARCH IN A LAW LIBRARY MICHAEL P. FORREST* MIKE MARTINEZ JR.** I. Introduction ............................................... 67 II. Trends in Print and Online Resources ..................... 68 III. Organization of the Law .................................. 69 IV. Primary Sources and Finding Aids ........................ 70 V. Legal Encyclopedias ...................................... 82 V I. C itators ................................................... 83 V II. Form books ................................................ 85 VIII. Reference Assistance ...................................... 85 I. INTRODUCTION This article targets as its audience pro se patrons'-individuals who cannot afford counsel and need to conduct their own legal research.2 The poor and disenfranchised have historically had difficulty getting equal ac- cess to justice. 3 One cause is simple: they cannot afford legal representa- * Michael P.