Habitat Use of Wintering Bird Communities in Sonora, Mexico: the Importance of Riparian Habitats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Species Accepted –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Swinhoe’S Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma Monorhis )

his is the 20th published report of the ABA Checklist Committee (hereafter, TCLC), covering the period July 2008– July 2009. There were no changes to commit - tee membership since our previous report (Pranty et al. 2008). Kevin Zimmer has been elected to serve his second term (to expire at the end of 2012), and Bill Pranty has been reelected to serve as Chair for a fourth year. During the preceding 13 months, the CLC final - ized votes on five species. Four species were accepted and added to the ABA Checklist , while one species was removed. The number of accepted species on the ABA Checklist is increased to 960. In January 2009, the seventh edition of the ABA Checklist (Pranty et al. 2009) was published. Each species is numbered from 1 (Black-bellied Whistling-Duck) to 957 (Eurasian Tree Sparrow); ancillary numbers will be inserted for all new species, and these numbers will be included in our annual reports. Production of the seventh edi - tion of the ABA Checklist occupied much of Pranty’s and Dunn’s time during the period, and this com - mitment helps to explain the relative paucity of votes during 2008–2009 compared to our other recent an - nual reports. New Species Accepted –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Swinhoe’s Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma monorhis ). ABA CLC Record #2009-02. One individual, thought to be a juvenile in slightly worn plumage, in the At - lantic Ocean at 3 4°5 7’ N, 7 5°0 5’ W, approximately 65 kilometers east-southeast of Hatteras Inlet, Cape Hat - teras, North Carolina on 2 June 2008. -

Nayarit, México Common Birds of the Marismas Nacionales Biosphere

NAYARIT, MÉXICO 1 COMMON BIRDS OF THE MARISMAS NACIONALES BIOSPHERE RESERVE Jesús Alberto Loc-Barragán1, José Antonio Robles-Martínez2, Jonathan Vargas-Vega3 and David Molina4 1Fotógrafos de Naturaleza A.C., 2Universidad Autónoma de Nayarit,UAT, 3Terra Peninsular A.C. and 4Estación Ornitológica “Sierra de San Juan-La Noria”, Nayarit Photos by: Jesús Loc, Antonio Robles, Jonathan Vargas, David Molina. Acknowledgments. To Emmanuel Miramontes, Carlos Villar, Stefanny Villagómez and Héctor Franz for the support of several photos indicated in the main text and to Tatzyana Wachter for the improvements to the document. © Jesús Alberto Loc-Barragán [[email protected]], José Antonio Robles-Martinez [[email protected]], Jonathan Vargas-Vega [[email protected]] and David Molina [[email protected]] [fieldguides.fieldmuseum.org] [921] version 1 8/2017 Signs: (R) = residente/resident, ( MI) = winter migratory, (SR) = summer resident; (♂) = Macho/Male, (♀) = Hembra/Female, (J) = Juvenil/Juvenile. Status of concern (Mexico) based on NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: PR: special protection; A: threatened; P: extinction risk; IUCN, LC: least concern; NT: near threatened; Endemism, E: endemic, CE: nearly endemic, SE: semiendemic, I; exotic, invasive. The numeric values are the Vulnerability index, which takes into account parameters like population size, geographic distribution, seasonal threats and population trend; index values vary from 4 until 20 and a higher value implies greater species vulnerability (Panjabi et al., 2005; Berlanga et al. 2015). Marismas Nacionales Biosphere Reserve and Birds In northwest Mexico, Marismas Nacionales, an extensive estuarine system, it has been historically recognized for its importance for birds, especially waterfowl, shorebirds, herons and coastal birds like gulls and terns (Leopold, 1959; Morrison et al., 1994; Ortega-Solís, 2011). -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Winter 2013 Volume 4, Issue 3 AZFO Elects New President

Arizona Field Ornithologists Arizona Field Ornithologists AZFO Studying Arizona Birds Winter 2013 Volume 4, Issue 3 AZFO ELECTS NEW PRESIDENT Visit us at By Doug Jenness http://azfo.org/ Kurt Radamaker has been elected to serve as the president of the AZFO for the next two years. He succeeds Troy Corman, who served in this capac- ity since the AZFO was founded eight years ago. Radamaker, a founding AZFO member, has served on the Board of Directors and developed the organi- zation’s website. He grew up in South- ern California where he started birding at the age of eight and by 15 had com- pleted Cornell Laboratory’s Seminars in Ornithology. He taught ornithology for four years at the University of La Verne, IN THIS ISSUE: a not-for-profit university near Los An- geles, and has led bird tours to several areas in the United States, Mexico, and Central with the presentation of an AZFO Achievement • AZFO New America. He has published numerous articles on Award. Although he is stepping down from cen- President birds, including in Arizona Birds Online, and is the tral executive responsibility, he plans to continue 1 author or a contributor to the following publica- to be active in the AZFO and to help out as need- tions: Arizona and New Mexico Birds (Lone Pine ed. Corman has worked for the Nongame Branch • Gale Monson Press, 2007); Species accounts for Bitterns, Her- of the Arizona Game and Fish Department since Grants ons and allies, and Ibises and Spoonbills in The 1990 and coordinated the Arizona Breeding Bird 1 Complete Guide to North American Birds (National Atlas project. -

Reminder an Unusual Species, High Count, Or Low Count

Christmas Bird Count Editorial Codes and Database Flags Two-letter codes are often used by regional editors to better explain or question a given record. Database flags can be set by compilers and regional editors to indicate Reminder an unusual species, high count, or low count. This list will aid you in deciphering The Christmas Bird Count is the keys when reading accounts in the summaries and on the web site. always held December 14 Code Comment Code Comment through January 5. AB albino NC new to count To find out the date of a specific AD adult ND no details count, go to the CBC home page AF at feeder NF not Forster’s <www.audubon.org/bird/cbc> AM adult male NH call not heard and click “Get Involved,” or AP alternate plumage NU not unusual? contact your local Audubon chapter or center. AQ adequate details OU origin unknown BD banded PD poor details DD details desired PH photo DM dark morph PS present for some time DW dark winged QN questionable number ED excellent details QU ? EO experienced observer RA radio collared ES estimated number RC record count EX exotic RI recent introduction FC first CBC record RN remarkable number Calling FE feral RP reintroduced population All Counters!y FP female-plumaged RR remarkable record We’re always looking for images to FS first state record RT responded to tape use in American Birds, such as FW first winter RW regular in winter photographs of birds seen during the GD good details SK sketch Christmas Bird Count or participants in HE high elevation SP specimen the field. -

Troglodytidae Species Tree

Troglodytidae I Rock Wren, Salpinctes obsoletus Canyon Wren, Catherpes mexicanus Sumichrast’s Wren, Hylorchilus sumichrasti Nava’s Wren, Hylorchilus navai Salpinctinae Nightingale Wren / Northern Nightingale-Wren, Microcerculus philomela Scaly-breasted Wren / Southern Nightingale-Wren, Microcerculus marginatus Flutist Wren, Microcerculus ustulatus Wing-banded Wren, Microcerculus bambla ?Gray-mantled Wren, Odontorchilus branickii Odontorchilinae Tooth-billed Wren, Odontorchilus cinereus Bewick’s Wren, Thryomanes bewickii Carolina Wren, Thryothorus ludovicianus Thrush-like Wren, Campylorhynchus turdinus Stripe-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus nuchalis Band-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus zonatus Gray-barred Wren, Campylorhynchus megalopterus White-headed Wren, Campylorhynchus albobrunneus Fasciated Wren, Campylorhynchus fasciatus Cactus Wren, Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus Yucatan Wren, Campylorhynchus yucatanicus Giant Wren, Campylorhynchus chiapensis Bicolored Wren, Campylorhynchus griseus Boucard’s Wren, Campylorhynchus jocosus Spotted Wren, Campylorhynchus gularis Rufous-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus capistratus Sclater’s Wren, Campylorhynchus humilis Rufous-naped Wren, Campylorhynchus rufinucha Pacific Wren, Nannus pacificus Winter Wren, Nannus hiemalis Eurasian Wren, Nannus troglodytes Zapata Wren, Ferminia cerverai Marsh Wren, Cistothorus palustris Sedge Wren, Cistothorus platensis ?Merida Wren, Cistothorus meridae ?Apolinar’s Wren, Cistothorus apolinari Timberline Wren, Thryorchilus browni Tepui Wren, Troglodytes rufulus Troglo dytinae Ochraceous -

Annotated List of Wetlands of International Importance Mexico

Ramsar Sites Information Service Annotated List of Wetlands of International Importance Mexico 142 Ramsar Site(s) covering 8,657,057 ha Agua Dulce Site number: 1,813 | Country: Mexico | Administrative region: Sonora Area: 39 ha | Coordinates: 31°55'N 113°01'W | Designation dates: 02-02-2008 View Site details in RSIS Agua Dulce. 02/02/08; Sonora; 39 ha; 31°55'N 113°01'W. Located within the Biosphere Reserve Del Picante y Desierto de Altar, which highlights the only riparian ecosystem of the region, Sonoyta river, considered of binational interest and shared between the USA and Mexico. At present, there is a mutual interest in establishing indicators for its management and conservation. Agua Dulce is a 3km stretch of the Sonoyta where water comes to the surface, creating conditions of an oasis in a desert. Among the main species found in the site is the Pupfish (Cyprinodon macularius), listed as endangered by the US and as endemic and endangered in Mexico's legal system. There is a considerable presence of the turtle species Kinonsternon sonoriense longifemorale. The resident and migratory bird species that use the Pacific Flyway find in Agua Dulce a habitat of importance for food, shelter, resting and reproduction. Agua Dulce is characteristic for retaining water throughout the year, acting as the main source of water for wildlife in the area, and supporting an excellent biological diversity. Ramsar site no. 1813. Most recent RIS information: 2008. Anillo de Cenotes Site number: 2,043 | Country: Mexico | Administrative region: Estado de Yucatán Area: 891 ha | Coordinates: 20°43'21"N 89°19'23"W | Designation dates: 02-02-2009 View Site details in RSIS Anillo de Cenotes. -

WB-V42(4)-Webcomp.Pdf

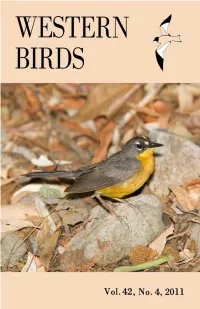

Volume 42, Number 4, 2011 Arizona Bird Committee Report, 2005–2009 Records Gary H. Rosenberg, Kurt Radamaker, and Mark M. Stevenson ..............198 Mitochondrial DNA and Meteorological Data Suggest a Caribbean Origin for New Mexico’s First Sooty Tern Andrew B. Johnson, Sabrina M. McNew, Matthew S. Graus, and Christopher C. Witt .............................233 NOTES Northerly Extension of the Breeding Range of the Roseate Spoonbill in Sonora, Mexico Abram B. Fleishman and Naomi S. Blinick ......243 Male-Plumaged Anna’s Hummingbird Feeds Chicks Elizabeth A. Mohr ...................................................................247 Severe Bill Deformity of an American Kestrel Wintering in California William M. Iko and Robert J. Dusek ......................251 Book Review Mike McDonald ...................................................255 Featured Photo: First Evidence for Eccentric Prealternate Molt in the Indigo Bunting: Possible Implications for Adaptive Molt Strategies Jared Wolfe and Peter Pyle ...................................257 Index Daniel D. Gibson .............................................................263 Front cover photo by © Charles W. Melton of Hereford, Arizona: Fan-tailed Warbler (Euthlypis lachrymosa), Madera Canyon, Santa Cruz County, Arizona, 24 May 2011. Back cover “Featured Photos” by © Peter Pyle of Point Reyes Sta- tion, California: Indigo Bunting (Passerina cyanea) more than one year old, captured 18 April 2011 in Cameron Parish, Louisiana, following eccentric prealternate molt (top); Indigo Bunting more -

Distribution and Status of Breeding Birds in the Sky Islands of Northern Sonora, Mexico

Distribution and Status of Breeding Birds in the Sky Islands of Northern Sonora, Mexico 2011 Annual Report Prepared by: Aaron D. Flesch1, Carlos González Sánchez, and Richard L. Hutto Avian Science Center Division of Biological Sciences University of Montana 32 Campus Drive Missoula, MT 59812 Office: 406-243-6499 [email protected] Prepared for: Nancy Wilcox Chiricahua National Monument 12856 East Rhyolite Creek Rd Willcox, AZ 85643 520-366-5515 [email protected] Oak woodland in the Sierra San Antonio December 2011 INTRODUCTION The Madrean Sky Islands region includes more than 30 distinct mountain ranges located at the northern end of the Sierra Madre Occidental and is bisected by the U.S.-Mexico border (McLaughlin 1995, Warshall 1995). The Sky Islands support isolated stands of montane vegetation dominated by pines (Pinus sp.) and oaks (Quercus sp.) that arise from lowland “seas” of desert scrub and grassland (Heald 1993). The Sky Islands region occupies portions of a broad transition zone between the Neartic and Neotropical faunal realms and supports flora and fauna with affinities to the Madrean, Petran (Rocky Mountain), Chihuahuan, Sinaloan, and Sonoran biogeographic provinces. Despite high diversity, little information is available to guide management and conservation planning in the Sky Islands of Mexico because knowledge of plant and animal distribution and ecological factors that drive distribution and diversity are limited (White 1948, Marshall 1957, Lomolino et al. 1989, Flesch 2008). In 2008, the National Park Service sponsored researchers at University of Arizona (UA) and University of Montana (UM) to work in collaboration with Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP) to describe bird communities and bird-habitat relationships throughout the Sky Islands region of northern Mexico. -

Birding 8-03 Pages 356-403

The Secret of the Predator’s Eyes. Steiner-Germany has developed the new Peregrine binocular, a new record in light transmission that al- lows faster discovery and location of birds hidden in foliage or shadows. Since birds are often visible for only a few seconds, seeing their true colors in bright contrast and clearly identifying the most subtle color differences is extremely important. With Steiner’s new Peregrine, a new level of brightness and natural color balance is achieved by use of a new dielectric prism coating, by which over 40 layers of titanium oxide and other rare minerals are alternately applied to the glass surfaces. This Broad-Band Coating (BBC) results in superior light transmission performance over a broad range of colors. The Peregrine is also phase corrected for sharpest possible, distortion free images and the optical glass is manufactured at our new state-of- the-art roof prism glass production facility in Bayreuth, Germany. The Peregrine falcon is a fast and skillful hunter, in fields and even under trees, aided by the sharpest eyes. The Steiner Peregrine is available in 8x42 and 10x42 models and will maintain its peak performance at any temperature and under any conditions. The Peregrine’s dark-green, light absorbing armored body blends in with natural surroundings, providing an advantage when glassing for easily spooked species. Take a look at the Steiner Peregrine or the new Merlin series at a Steiner Dealer near you soon. www.steiner-birding.com 8x42 Peregrine 10x42 Peregrine 8x32 Merlin 8x42 Merlin 10x42 Merlin 1-800-257-7742 SPONSOR $849 $899 $399 $449 $499 FINDING BIRDS IN MEXICO SanSan Blas:Blas: Big-Time Birding in a Small Tropical Town by Noah K. -

Flycatcher, Please Contact Matt Griffiths at Board Committees Conservation Chair Chris Mcvie, [email protected]

THE QUARTERLY NEWS MAGAZINE OF TUCSON AUDUBON SOCIETY | TUCSONAUDUBON.ORG VermFLYCATCHERilion January–March 2014 | Volume 59, Number 1 Changes The More Things Stay the Same Changes in Latitude or Changes in Attitude Cave Creek Complex Tucson Meet Your Birds What’s in a Name: Sinaloa Wren and Happy Wren Features THE QUARTERLY NEWS MAGAZINE OF TUCSON AUDUBON SOCIETY | TUCSONAUDUBON.ORG 12 Tucson Meet Your Birds 14 The More Things Stay the Same VermFLYCATCHERilion 16 Changes in Latitude or January–March 2014 | Volume 59, Number 1 Changes in Attitude Changes The More Things Stay the Same Tucson Audubon Society is dedicated to improving 18 Cave Creek Canyon Complex, Changes in Latitude or Changes in Attitude the quality of the environment by providing Chiricahua Mountains environmental leadership, information, and programs 19 What’s in a Name: Sinaloa Wren and for education, conservation, and recreation. Tucson Audubon is a non-profit volunteer organization of Happy Wren people with a common interest in birding and natural history. Tucson Audubon maintains offices, a library, and nature shops in Tucson, the proceeds of which Departments benefit all of its programs. 4 Events and Classes Tucson Audubon Society 5 Events Calendar 300 E. University Blvd. #120, Tucson, AZ 85705 6 Living with Nature Lecture Series 629-0510 (voice) or 623-3476 (fax) Cave Creek Complex All phone numbers are area code 520 unless otherwise stated. 7 News Roundup Tucson Meet Your Birds What’s in a Name: Sinaloa Wren tucsonaudubon.org 11 Birdathon Board Officers & Directors 20 Conservation and Education News President Cynthia Pruett FRONT COVER: Rufous-capped Warbler by Jeremy Vice President Bob Hernbrode 24 Birding Travel from Our Business Partners Hayes. -

The 109Th Christmas Bird Count American Birds Volume 63

The 109th Christmas Bird Count American Birds Volume 63 Published by the National Audubon Society 225 Varick Street, 7th floor New York, NY 10014 October 2009 G. Thomas Bancroft Vice-President and Chief Scientist Geoffrey S. LeBaron Director, Christmas Bird Count and Editor-in-Chief Birders may not often think of American Coots (Fulica americana) as lovely photo- Greg Butcher graphic subjects, but these coots in motion at Clear Lake, California, provide just such Director, Bird Conservation an image. Photo/Barbara Bridges Kathy Dale Director of IT, Audubon Science CONTENTS Richard J. Cannings The 109th Christmas Bird Count . .2 Christmas Bird Count Coordinator, Geoffrey S. LeBaron Bird Studies Canada The 109th Christmas Bird Count in Canada . .8 Avery English-Elliott Richard J. Cannings Ruth Helmich Christmas Bird Count Assistants Christmas Bird Counts and Climate Change: Northward Shifts in Early Winter Abundance . .10 Connie Isbell Daniel K. Niven, Gregory S. Butcher, and G. Thomas Bancroft Managing Editor Four Hundred and Counting: Mickey Boisvert Reflections on a Long Association with the Christmas Bird Count . .16 www.mbdesign-us.com Art Director/Graphic Designer Paul W. Sykes Jr. Greg Merhar Not Just a Walk in the Park: New York’s Central Park Christmas Bird Count . .24 Graphics Associate Sarah McCarn Elliott Caroline Jackson On the Ice: The First Christmas Bird Count in Antarctica . .30 GIS Technician Noah Strycker Heidi DeVos The Birds of Christmas in London, Ontario: One Hundred Years and Going Strong . .35 Production Director Peter Read Gregory P. Licciardi Pictorial Highlights . .40 Managing Director of Advertising Alphabetical Index to Regional Summaries .