PPCO Twist System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NH Bird Records

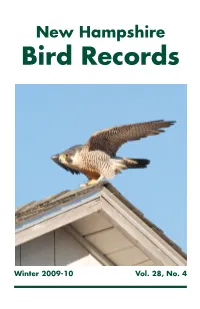

V28 No4-Winter09-10_f 8/22/10 4:45 PM Page i New Hampshire Bird Records Winter 2009-10 Vol. 28, No. 4 V28 No4-Winter09-10_f 8/22/10 4:45 PM Page ii AUDUBON SOCIETY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE New Hampshire Bird Records Volume 28, Number 4 Winter 2009-10 Managing Editor: Rebecca Suomala 603-224-9909 X309, [email protected] Text Editor: Dan Hubbard Season Editors: Pamela Hunt, Spring; Tony Vazzano, Summer; Stephen Mirick, Fall; David Deifik, Winter Layout: Kathy McBride Assistants: Jeannine Ayer, Lynn Edwards, Margot Johnson, Susan MacLeod, Marie Nickerson, Carol Plato, William Taffe, Jean Tasker, Tony Vazzano Photo Quiz: David Donsker Photo Editor: Jon Woolf Web Master: Len Medlock Editorial Team: Phil Brown, Hank Chary, David Deifik, David Donsker, Dan Hubbard, Pam Hunt, Iain MacLeod, Len Medlock, Stephen Mirick, Robert Quinn, Rebecca Suomala, William Taffe, Lance Tanino, Tony Vazzano, Jon Woolf Cover Photo: Peregrine Falcon by Jon Woolf, 12/1/09, Hampton Beach State Park, Hampton, NH. New Hampshire Bird Records is published quarterly by New Hampshire Audubon’s Conservation Department. Bird sight- ings are submitted to NH eBird (www.ebird.org/nh) by many different observers. Records are selected for publication and not all species reported will appear in the issue. The published sightings typically represent the highlights of the season. All records are subject to review by the NH Rare Birds Committee and publication of reports here does not imply future acceptance by the Committee. Please contact the Managing Editor if you would like to report your sightings but are unable to use NH eBird. -

January 2020.Indd

BROWN PELICAN Photo by Rob Swindell at Melbourne, Florida JANUARY 2020 Editors: Jim Jablonski, Marty Ackermann, Tammy Martin, Cathy Priebe Webmistress: Arlene Lengyel January 2020 Program Tuesday, January 7, 2020, 7 p.m. Carlisle Reservation Visitor Center Gulls 101 Chuck Slusarczyk, Jr. "I'm happy to be presenting my program Gulls 101 to the good people of Black River Audubon. Gulls are notoriously difficult to identify, but I hope to at least get you looking at them a little closer. Even though I know a bit about them, I'm far from an expert in the field and there is always more to learn. The challenge is to know the particular field marks that are most important, and familiarization with the many plumage cycles helps a lot too. No one will come out of this presentation an expert, but I hope that I can at least give you an idea what to look for. At the very least, I hope you enjoy the photos. Looking forward to seeing everyone there!” Chuck Slusarczyk is an avid member of the Ohio birding community, and his efforts to assist and educate novice birders via social media are well known, yet he is the first to admit that one never stops learning. He has presented a number of programs to Black River Audubon, always drawing a large, appreciative gathering. 2019 Wellington Area Christmas Bird Count The Wellington-area CBC will take place Saturday, December 28, 2019. Meet at the McDonald’s on Rt. 58 at 8:00 a.m. The leader is Paul Sherwood. -

New Species Accepted –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Swinhoe’S Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma Monorhis )

his is the 20th published report of the ABA Checklist Committee (hereafter, TCLC), covering the period July 2008– July 2009. There were no changes to commit - tee membership since our previous report (Pranty et al. 2008). Kevin Zimmer has been elected to serve his second term (to expire at the end of 2012), and Bill Pranty has been reelected to serve as Chair for a fourth year. During the preceding 13 months, the CLC final - ized votes on five species. Four species were accepted and added to the ABA Checklist , while one species was removed. The number of accepted species on the ABA Checklist is increased to 960. In January 2009, the seventh edition of the ABA Checklist (Pranty et al. 2009) was published. Each species is numbered from 1 (Black-bellied Whistling-Duck) to 957 (Eurasian Tree Sparrow); ancillary numbers will be inserted for all new species, and these numbers will be included in our annual reports. Production of the seventh edi - tion of the ABA Checklist occupied much of Pranty’s and Dunn’s time during the period, and this com - mitment helps to explain the relative paucity of votes during 2008–2009 compared to our other recent an - nual reports. New Species Accepted –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Swinhoe’s Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma monorhis ). ABA CLC Record #2009-02. One individual, thought to be a juvenile in slightly worn plumage, in the At - lantic Ocean at 3 4°5 7’ N, 7 5°0 5’ W, approximately 65 kilometers east-southeast of Hatteras Inlet, Cape Hat - teras, North Carolina on 2 June 2008. -

Species List (Note, There Was a Pre-Tour to Kenya in 2018 As in 2017, but These Species Were Not Recorded

Tanzania Species List (Note, there was a pre-tour to Kenya in 2018 as in 2017, but these species were not recorded. You can find a Kenya list with the fully annotated 2017 Species List for reference) February 6-18, 2018 Guides: Preston Mutinda and Peg Abbott, Driver/guides William Laiser and John Shoo, and 6 participants: Rob & Anita, Susan and Jan, and Bob and Joan KEYS FOR THIS LIST The # in (#) is the number of days the species was seen on the tour (E) – endemic BIRDS STRUTHIONIDAE: OSTRICHES OSTRICH Struthio camelus massaicus – (8) ANATIDAE: DUCKS & GEESE WHITE-FACED WHISTLING-DUCK Dendrocygna viduata – (2) FULVOUS WHISTLING-DUCK Dendrocygna bicolor – (1) COMB DUCK Sarkidiornis melanotos – (1) EGYPTIAN GOOSE Alopochen aegyptiaca – (12) SPUR-WINGED GOOSE Plectropterus gambensis – (2) RED-BILLED DUCK Anas erythrorhyncha – (4) HOTTENTOT TEAL Anas hottentota – (2) CAPE TEAL Anas capensis – (2) NUMIDIDAE: GUINEAFOWL HELMETED GUINEAFOWL Numida meleagris – (12) PHASIANIDAE: PHEASANTS, GROUSE, AND ALLIES COQUI FRANCOLIN Francolinus coqui – (2) CRESTED FRANCOLIN Francolinus sephaena – (2) HILDEBRANDT'S FRANCOLIN Francolinus hildebrandti – (3) Naturalist Journeys [email protected] 866.900.1146 / Caligo Ventures [email protected] 800.426.7781 naturalistjourneys.com / caligo.com P.O. Box 16545 Portal AZ 85632 FAX: 650.471.7667 YELLOW-NECKED FRANCOLIN Francolinus leucoscepus – (4) [E] GRAY-BREASTED FRANCOLIN Francolinus rufopictus – (4) RED-NECKED FRANCOLIN Francolinus afer – (2) LITTLE GREBE Tachybaptus ruficollis – (1) PHOENICOPTERIDAE:FLAMINGOS -

Ornithological Expedition to Southern Bénin, April 2011

Ornithological expedition to southern Bénin, April 2011 Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire & Robert J. Dowsett Dowsett-Lemaire Misc. Report 80 (2011) Dowsett-Lemaire F. & Dowsett R.J. 2011. Ornithological expedition to southern Bénin, April 2011. Dowsett-Lemaire Miscellaneous Report 80: 16pp. Birds of southern Bénin -1- Dowsett-Lemaire Misc. Rep. 80 (2011) Ornithological expedition to southern Bénin, April 2011 by Françoise Dowsett-Lemaire & Robert J. Dowsett Résumé Ceci est notre deuxième visite au sud du Bénin, faisant suite à une première expédition pendant la saison sèche de 2009. Le mois d’avril 2011 a été partagé entre les forêts principales du sud (Lama, Niaouli), les forêts plus sèches ou forêts claires des Monts Kouffé et Tobé à l’ouest, les plaines marécageuses du Zou et du Sô, et la zone côtière (Pahou et Grand-Popo). Un séjour du 12 au 16 avril à la limite sud des Monts Kouffé et dans la zone protégée de Tobé (Bantè) a permis d’étendre l’aire de distribution de plusieurs espèces forestières ou de sa - vane, notamment du rare Aigle couronné Stephanoaetus coronatus (un ex. essayant de capturer un Daman des rochers sur le rocher de Tobé), du Râle perlé Sarothrura pulchra (un chanteur à Tobé, limite nord actuelle), de l’Oedicnème tachard Burhinus capensis (Tobé, limite sud actuelle), Malcoha à bec jaune Ceuthmochares aereus (Tobé & Kouffé, limite nord), Coucal à ventre blanc Centropus leucogaster (Tobé & Kouffé, limite nord), Grand-duc de Verreaux Bubo lacteus (Kouffé), Trogon narina Apaloderma narina (Kouffé), Calao rieur By - canistes -

Nayarit, México Common Birds of the Marismas Nacionales Biosphere

NAYARIT, MÉXICO 1 COMMON BIRDS OF THE MARISMAS NACIONALES BIOSPHERE RESERVE Jesús Alberto Loc-Barragán1, José Antonio Robles-Martínez2, Jonathan Vargas-Vega3 and David Molina4 1Fotógrafos de Naturaleza A.C., 2Universidad Autónoma de Nayarit,UAT, 3Terra Peninsular A.C. and 4Estación Ornitológica “Sierra de San Juan-La Noria”, Nayarit Photos by: Jesús Loc, Antonio Robles, Jonathan Vargas, David Molina. Acknowledgments. To Emmanuel Miramontes, Carlos Villar, Stefanny Villagómez and Héctor Franz for the support of several photos indicated in the main text and to Tatzyana Wachter for the improvements to the document. © Jesús Alberto Loc-Barragán [[email protected]], José Antonio Robles-Martinez [[email protected]], Jonathan Vargas-Vega [[email protected]] and David Molina [[email protected]] [fieldguides.fieldmuseum.org] [921] version 1 8/2017 Signs: (R) = residente/resident, ( MI) = winter migratory, (SR) = summer resident; (♂) = Macho/Male, (♀) = Hembra/Female, (J) = Juvenil/Juvenile. Status of concern (Mexico) based on NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: PR: special protection; A: threatened; P: extinction risk; IUCN, LC: least concern; NT: near threatened; Endemism, E: endemic, CE: nearly endemic, SE: semiendemic, I; exotic, invasive. The numeric values are the Vulnerability index, which takes into account parameters like population size, geographic distribution, seasonal threats and population trend; index values vary from 4 until 20 and a higher value implies greater species vulnerability (Panjabi et al., 2005; Berlanga et al. 2015). Marismas Nacionales Biosphere Reserve and Birds In northwest Mexico, Marismas Nacionales, an extensive estuarine system, it has been historically recognized for its importance for birds, especially waterfowl, shorebirds, herons and coastal birds like gulls and terns (Leopold, 1959; Morrison et al., 1994; Ortega-Solís, 2011). -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

The Birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an Annotated Checklist

European Journal of Taxonomy 306: 1–69 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.306 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Gedeon K. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A32EAE51-9051-458A-81DD-8EA921901CDC The birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an annotated checklist Kai GEDEON 1,*, Chemere ZEWDIE 2 & Till TÖPFER 3 1 Saxon Ornithologists’ Society, P.O. Box 1129, 09331 Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany. 2 Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise, P.O. Box 1075, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 3 Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Centre for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F46B3F50-41E2-4629-9951-778F69A5BBA2 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F59FEDB3-627A-4D52-A6CB-4F26846C0FC5 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A87BE9B4-8FC6-4E11-8DB4-BDBB3CFBBEAA Abstract. Oromia is the largest National Regional State of Ethiopia. Here we present the first comprehensive checklist of its birds. A total of 804 bird species has been recorded, 601 of them confirmed (443) or assumed (158) to be breeding birds. At least 561 are all-year residents (and 31 more potentially so), at least 73 are Afrotropical migrants and visitors (and 44 more potentially so), and 184 are Palaearctic migrants and visitors (and eight more potentially so). Three species are endemic to Oromia, 18 to Ethiopia and 43 to the Horn of Africa. 170 Oromia bird species are biome restricted: 57 to the Afrotropical Highlands biome, 95 to the Somali-Masai biome, and 18 to the Sudan-Guinea Savanna biome. -

BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis Mcintosh

COM . TOCK S HUTTER © S © BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis McIntosh For passionate birdwatcher Sandy Komito of over age 16 say they actively observe and try to iden- Fair Lawn, New Jersey, 1998 was a big year. In a tify birds, although few go to the extremes Komito tight competition with two fellow birders to see as did. About 88 percent are content to enjoy bird many species as possible in a single year, Komito watching in their own backyards or neighborhoods. traveled 270,000 miles, crisscrossing North Amer- More avid participants plan vacations around ica and voyaging far out to sea to locate rare and their hobby and sometimes travel long distances to elusive birds. In the end, he set a North American view a rare species and add it to their lifelong list of record of 748 species, topping his own previous birds spotted. Many birdwatchers, both casual and record of 726, which had stood for 11 years. serious, also function as citizen scientists, provid- Komito and his fellow competitors are not alone ing valuable data to help scientists monitor bird in their love of birds. According to a U.S. Fish and populations and create management guidelines to Wildlife Service survey, about one in five Americans protect species in decline. 36 2 0 1 4 N UMBER 1 | E NGLISH T E ACHING F ORUM Birding Basics The origins of bird watching in the United States date back to the late 1800s when conserva- tionists became concerned about the hunting of birds to supply feathers for the fashion industry. -

Phylogeography of Finches and Sparrows

In: Animal Genetics ISBN: 978-1-60741-844-3 Editor: Leopold J. Rechi © 2009 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 1 PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF FINCHES AND SPARROWS Antonio Arnaiz-Villena*, Pablo Gomez-Prieto and Valentin Ruiz-del-Valle Department of Immunology, University Complutense, The Madrid Regional Blood Center, Madrid, Spain. ABSTRACT Fringillidae finches form a subfamily of songbirds (Passeriformes), which are presently distributed around the world. This subfamily includes canaries, goldfinches, greenfinches, rosefinches, and grosbeaks, among others. Molecular phylogenies obtained with mitochondrial DNA sequences show that these groups of finches are put together, but with some polytomies that have apparently evolved or radiated in parallel. The time of appearance on Earth of all studied groups is suggested to start after Middle Miocene Epoch, around 10 million years ago. Greenfinches (genus Carduelis) may have originated at Eurasian desert margins coming from Rhodopechys obsoleta (dessert finch) or an extinct pale plumage ancestor; it later acquired green plumage suitable for the greenfinch ecological niche, i.e.: woods. Multicolored Eurasian goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) has a genetic extant ancestor, the green-feathered Carduelis citrinella (citril finch); this was thought to be a canary on phonotypical bases, but it is now included within goldfinches by our molecular genetics phylograms. Speciation events between citril finch and Eurasian goldfinch are related with the Mediterranean Messinian salinity crisis (5 million years ago). Linurgus olivaceus (oriole finch) is presently thriving in Equatorial Africa and was included in a separate genus (Linurgus) by itself on phenotypical bases. Our phylograms demonstrate that it is and old canary. Proposed genus Acanthis does not exist. Twite and linnet form a separate radiation from redpolls. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Ghana Mega Rockfowl & Upper Guinea Specials 3 to 25 January 2016 (23 Days) Trip Report

Knox Ghana Mega Rockfowl & Upper Guinea Specials 3 to 25 January 2016 (23 days) Trip Report Akun Eagle-Owl by David Hoddinott Trip Report compiled by Tour Leader Markus Lilje RBT Knox Ghana Mega Trip Report January 2015 2 Trip Summary Our private Ghana Mega trip proved yet again to be a resounding success! We notched up a fantastic species total in 23 days, where we covered the length and breadth of the country and a great variety of habitats in this superb West African country! Our tour started off with a visit to Shai Hills. This small but fabulous reserve has a nice variety of habitats including mixed woodland, grassland, wetlands and granite outcrops and therefore supports an interesting array of bird species. During our morning exploring the reserve we recorded African Cuckoo-Hawk, Western Marsh Harrier, Red-necked Buzzard, stunning Violet Turaco, numerous immaculate Blue-bellied Roller, Vieillot’s and Double-toothed Barbets, Senegal and African Wattled Lapwings, White-shouldered Black Tit, Red- shouldered Cuckooshrike, Black-bellied Bustard, Senegal Parrot, Senegal Batis and restless Senegal Eremomela. A number of migrants were seen including Willow Warbler, Whinchat and Spotted Flycatcher. Even mammals showed well for us as we had a number of Kob, Bushbuck, Olive Baboon, Callithrix Monkey and unusually good views of Lesser Spot- Blue-bellied Roller by Markus Lilje nosed Monkey! Well pleased with our morning’s birding, we left Shai Hills and made our way to Ho. En route we stopped for lunch near the Volta Dam where we enjoyed most memorable close-up encounters with Mangrove Sunbird and Bronze- tailed Starling.