Faith No More V. Manifesto Records, Inc., Not Reported in Cal.Rptr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

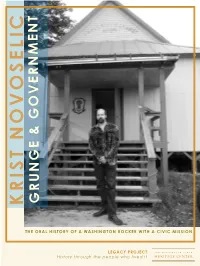

Krist Novoselic

OVERNMENT G & E GRUNG KRIST NOVOSELIC THE ORAL HISTORY OF A WASHINGTON ROCKER WITH A CIVIC MISSION LEGACY PROJECT History through the people who lived it Krist Novoselic Research by John Hughes and Lori Larson Transcripti on by Lori Larson Interviews by John Hughes October 14, 2008 John Hughes: This is October 14, 2008. I’m John Hughes, Chief Oral Historian for the Washington State Legacy Project, with the Offi ce of the Secretary of State. We’re in Deep River, Wash., at the home of Krist Novoselic, a 1984 graduate of Aberdeen High School; a founding member of the band Nirvana with his good friend Kurt Cobain; politi cal acti vist, chairman of the Wahkiakum County Democrati c Party, author, fi lmmaker, photographer, blogger, part-ti me radio host, While doing reseach at the State Archives in 2005, Novoselic volunteer disc jockey, worthy master of the Grays points to Grays River in Wahkiakum County, where he lives. Courtesy Washington State Archives River Grange, gentleman farmer, private pilot, former commercial painter, ex-fast food worker, proud son of Croati a, and an amateur Volkswagen mechanic. Does that prett y well cover it, Krist? Novoselic: And chairman of FairVote to change our democracy. Hughes: You know if you ever decide to run for politi cal offi ce, your life is prett y much an open book. And half of it’s on YouTube, like when you tried for the Guinness Book of World Records bass toss on stage with Nirvana and it hits you on the head, and then Kurt (Cobain) kicked you in the butt . -

Download Free TOTO MULTITRACK Best Free Multitrack Recording Software for Mac/Windows

download free TOTO MULTITRACK Best Free Multitrack Recording Software for Mac/Windows. Are you looking for the best free multitrack recording software for Mac/Windows? Actually, there are many free multitrack recording tools for you to make use of. Whether you want to edit or record your own compositions or just desire to start your own podcasts, you can take advantage of the free multitrack audio recorder to make it. This guidance will introduce some of them and take one for instance to teach you the steps to record one multitrack audio. You will also learn the solution to add music tags to the recordings in this tutorial. Part 1: Top 5 Best Free Multitrack Recording Software for Mac/Windows Part 2: How to Record Multitrack Audio via MultitrackStudio Extension: How to Add Music Tags to the Recordings Automatically. Part 1: Top 5 Best Free Multitrack Recording Software for Mac/Windows. The free multitrack recording software reviews can reflect the quality of the tool directly. Different multitrack recording tools have diverse features. You can compare them one by one, but this will take you much time. In order to save you time, you can read this part to get rid of this issue perfectly. Here I would like to recommend you the top 5 best free multitrack music recording software for your computer. Each tool is convenient for you to make use. Before your downloading and installing, you need to pay attention to the system that the multitrack recording software can be applied to. 1. Garageband. This free multitrack recording software is released in 2004, which is one popular DAW. -

The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989

The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989 New Wave, Punk-rock, Hardcore History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) The Golden Age of Heavy Metal (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") The pioneers 1976-78 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. Heavy-metal in the 1970s was Blue Oyster Cult, Aerosmith, Kiss, AC/DC, Journey, Boston, Rush, and it was the most theatrical and brutal of rock genres. It was not easy to reconcile this genre with the anti-heroic ethos of the punk era. It could have seemed almost impossible to revive that genre, that was slowly dying, in an era that valued the exact opposite of machoism, and that was producing a louder and noisier genre, hardcore. Instead, heavy metal began its renaissance in the same years of the new wave, capitalizing on the same phenomenon of independent labels. Credit goes largely to a British contingent of bands, that realized how they could launch a "new wave of British heavy metal" during the new wave of rock music. Motorhead (1), formed by ex-Hawkwind bassist Ian "Lemmy" Kilminster, were the natural bridge between heavy metal, Stooges/MC5 and punk-rock. They played demonic, relentless rock'n'roll at supersonic speed: Iron Horse (1977), Metropolis (1979), Bomber (1979), Jailbait (1980), Iron Fist (1982), etc. -

Black Sabbath the Complete Guide

Black Sabbath The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 17 May 2010 12:17:46 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Black Sabbath 1 The members 23 List of Black Sabbath band members 23 Vinny Appice 29 Don Arden 32 Bev Bevan 37 Mike Bordin 39 Jo Burt 43 Geezer Butler 44 Terry Chimes 47 Gordon Copley 49 Bob Daisley 50 Ronnie James Dio 54 Jeff Fenholt 59 Ian Gillan 62 Ray Gillen 70 Glenn Hughes 72 Tony Iommi 78 Tony Martin 87 Neil Murray 90 Geoff Nicholls 97 Ozzy Osbourne 99 Cozy Powell 111 Bobby Rondinelli 118 Eric Singer 120 Dave Spitz 124 Adam Wakeman 125 Dave Walker 127 Bill Ward 132 Related bands 135 Heaven & Hell 135 Mythology 140 Discography 141 Black Sabbath discography 141 Studio albums 149 Black Sabbath 149 Paranoid 153 Master of Reality 157 Black Sabbath Vol. 4 162 Sabbath Bloody Sabbath 167 Sabotage 171 Technical Ecstasy 175 Never Say Die! 178 Heaven and Hell 181 Mob Rules 186 Born Again 190 Seventh Star 194 The Eternal Idol 197 Headless Cross 200 Tyr 203 Dehumanizer 206 Cross Purposes 210 Forbidden 212 Live Albums 214 Live Evil 214 Cross Purposes Live 218 Reunion 220 Past Lives 223 Live at Hammersmith Odeon 225 Compilations and re-releases 227 We Sold Our Soul for Rock 'n' Roll 227 The Sabbath Stones 230 Symptom of the Universe: The Original Black Sabbath 1970–1978 232 Black Box: The Complete Original Black Sabbath 235 Greatest Hits 1970–1978 237 Black Sabbath: The Dio Years 239 The Rules of Hell 243 Other related albums 245 Live at Last 245 The Sabbath Collection 247 The Ozzy Osbourne Years 249 Nativity in Black 251 Under Wheels of Confusion 254 In These Black Days 256 The Best of Black Sabbath 258 Club Sonderauflage 262 Songs 263 Black Sabbath 263 Changes 265 Children of the Grave 267 Die Young 270 Dirty Women 272 Disturbing the Priest 273 Electric Funeral 274 Evil Woman 275 Fairies Wear Boots 276 Hand of Doom 277 Heaven and Hell 278 Into the Void 280 Iron Man 282 The Mob Rules 284 N. -

Liug Under Gh%Oijni)

L,I LIUG UNDER GH%OIJNI) day 1990 2 SLUG May -h CHICASAW MUD PUPPIES BOXCAR KIDS FRACTAL METHOD iHE RHJE UPS %=-m~--=2zz!z--------w---w--ww, FATES THURSDAY, MAY 10 SANCTUARY -THE STENCH THE ST&H ~wooo~ommoo~~~~m ----------------mm~oo~ommoo~~~~~ FRIDAY, MAY 11 mwwwwwww~4 mooooooo~ -----------~~~00000004 [DAY, MAY 20 JUNE 2 - LOvE/HArn JUNE 6 - FUGAZI JUNE 9 - IVIDC, GUILT PARADE, BASIC BLACK 3 JUNE 13 - SOCIAL DISTORTION and GANG GREEN TOOTS & THE MAYTALS SLUG May 3 credits & shit portraits -. Editor/mblisher J.R. Ruppel Copy Editor Rick Ruppel Photographs Steve Midgley .- JohnZeile Layout - Alisa ~unsakir Sales - Paul Maritsas 'Il~eoplnloihd tiem expremd La thh rap ue tbore dthe writen and are not necuaulty thow d the ldiotr abo put thL rhlt bgehr-ao back otfnun! 8AUM.W.IWQ SLUG is prlnted on the first ol each month and Is free to the publk. The wrftten material Is provided by YOU. Your oplnions are vital!! Please feel free to send what you have-letters, Artidea, Art work, Reviews, Poetry, Photos, Conce? and Event Information to us by the2Otb of each month to,.. P.O. Box 1061 Salt Lake City, Utah 84110-1061 . -.. ,. ,. .. - +-.* ..;.ar I- dial .5321$?33 , or Wn:te4tbP.O. Box 561, Salt Lake Ciiy Utah, 84110-561 lREN W;NG,! DUSTRIAUUNDERGROUND . DANCE MUSIC I NERY TUESDAY, 9PM TO 1AM I ATJOHNNY B'S BACK STAGE - I 65 NORTH UNIVERSITY AVE. PROVO I, DEAR DICKHEADS..... BLAH, BLAH, BLAH bear Dickheads, is better than receiving false and Due to media influeyes which is Theendof eachmonthholdsmuch Ed.Note:Dear Mr. -

Album Top 1000 2021

2021 2020 ARTIEST ALBUM JAAR ? 9 Arc%c Monkeys Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not 2006 ? 12 Editors An end has a start 2007 ? 5 Metallica Metallica (The Black Album) 1991 ? 4 Muse Origin of Symmetry 2001 ? 2 Nirvana Nevermind 1992 ? 7 Oasis (What's the Story) Morning Glory? 1995 ? 1 Pearl Jam Ten 1992 ? 6 Queens Of The Stone Age Songs for the Deaf 2002 ? 3 Radiohead OK Computer 1997 ? 8 Rage Against The Machine Rage Against The Machine 1993 11 10 Green Day Dookie 1995 12 17 R.E.M. Automa%c for the People 1992 13 13 Linkin' Park Hybrid Theory 2001 14 19 Pink floyd Dark side of the moon 1973 15 11 System of a Down Toxicity 2001 16 15 Red Hot Chili Peppers Californica%on 2000 17 18 Smashing Pumpkins Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness 1995 18 28 U2 The Joshua Tree 1987 19 23 Rammstein Muaer 2001 20 22 Live Throwing Copper 1995 21 27 The Black Keys El Camino 2012 22 25 Soundgarden Superunknown 1994 23 26 Guns N' Roses Appe%te for Destruc%on 1989 24 20 Muse Black Holes and Revela%ons 2006 25 46 Alanis Morisseae Jagged Liale Pill 1996 26 21 Metallica Master of Puppets 1986 27 34 The Killers Hot Fuss 2004 28 16 Foo Fighters The Colour and the Shape 1997 29 14 Alice in Chains Dirt 1992 30 42 Arc%c Monkeys AM 2014 31 29 Tool Aenima 1996 32 32 Nirvana MTV Unplugged in New York 1994 33 31 Johan Pergola 2001 34 37 Joy Division Unknown Pleasures 1979 35 36 Green Day American idiot 2005 36 58 Arcade Fire Funeral 2005 37 43 Jeff Buckley Grace 1994 38 41 Eddie Vedder Into the Wild 2007 39 54 Audioslave Audioslave 2002 40 35 The Beatles Sgt. -

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught up in You .38 Special Hold on Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught Up in You .38 Special Hold On Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down When You're Young 30 Seconds to Mars Attack 30 Seconds to Mars Closer to the Edge 30 Seconds to Mars The Kill 30 Seconds to Mars Kings and Queens 30 Seconds to Mars This is War 311 Amber 311 Beautiful Disaster 311 Down 4 Non Blondes What's Up? 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect The 88 Sons and Daughters a-ha Take on Me Abnormality Visions AC/DC Back in Black (Live) AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (Live) AC/DC Fire Your Guns (Live) AC/DC For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) (Live) AC/DC Heatseeker (Live) AC/DC Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) AC/DC Hells Bells (Live) AC/DC Highway to Hell (Live) AC/DC The Jack (Live) AC/DC Moneytalks (Live) AC/DC Shoot to Thrill (Live) AC/DC T.N.T. (Live) AC/DC Thunderstruck (Live) AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie (Live) AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long (Live) Ace Frehley Outer Space Ace of Base The Sign The Acro-Brats Day Late, Dollar Short The Acro-Brats Hair Trigger Aerosmith Angel Aerosmith Back in the Saddle Aerosmith Crazy Aerosmith Cryin' Aerosmith Dream On (Live) Aerosmith Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Eat the Rich Aerosmith I Don't Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Janie's Got a Gun Aerosmith Legendary Child Aerosmith Livin' On the Edge Aerosmith Love in an Elevator Aerosmith Lover Alot Aerosmith Rag Doll Aerosmith Rats in the Cellar Aerosmith Seasons of Wither Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Aerosmith Toys in the Attic Aerosmith Train Kept A Rollin' Aerosmith Walk This Way AFI Beautiful Thieves AFI End Transmission AFI Girl's Not Grey AFI The Leaving Song, Pt. -

Current, November 13, 2017 University of Missouri-St

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Current (2010s) Student Newspapers 11-13-2017 Current, November 13, 2017 University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s Recommended Citation University of Missouri-St. Louis, "Current, November 13, 2017" (2017). Current (2010s). 285. https://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s/285 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Current (2010s) by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vol. 51 Issue 1547 The Current November 13, 2017 UMSL’S INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWS UMSL Students Take First Place for Civic Engagement Nationally KAT RIDDLER of eligible UMSL students voted last nor’s office where students can learn with Associated Students of Univer- planning for voter registration and Managing Editor November. more about how to serve on state sity of Missouri to host lunch-and- education efforts in fall 2018. UMSL students voted at a 17 per- boards and commissions, working learns for local elected officials, and atricia Zahn, Director of Com- cent higher rate than students na- Pmunity Outreach & Engage- tionally when controlled for factors ment, was a guest speaker at the such as the age of the school’s stu- Student Government Association dent population according to UMSL General Assembly Meeting on No- Daily. vember 10. Zahn carried two awards Zahn was pleased to share that up with her to the podium to speak UMSL also competed in the All about student voting. -

Fan Q & a with JIM MARTIN, Formerly of FAITH NO MORE

For Immediate Release November 13, 2012 Fan Q & A with JIM MARTIN, Formerly of FAITH NO MORE After a silence of over a decade, Jim Martin agreed to a Q&A session with fans via a British based fan site. A set of 15 questions were selected by administrators of the fan site from over 500 submissions by fans eager to hear from Jim. What follows is a Q&A session with Jim Martin, former Faith No More guitar player, songwriter, and producer, and fans of Faith No More. Some weeks ago, the FNM “fan club guy” was asking about how to contact me, he wanted to talk to me about the fan page.. After several exchanges via email, he and I decided to do a Q&A thing for the fans. My departure from FNM in 1993 was controversial; I left while the band was still at the peak of its success. I am proud of my contributions to the success and legacy of FNM. I appreciate the time and effort it took to put these questions together. Thank you for the opportunity 1. Nefertiti Malaty Q: What do you consider the highlight of your career? A: Performing with Bo Diddly, Klaus Mein, Metallica, Gary Rossington, Pepper Keenan Sean Kinney Jerry Cantrell John Popper Jason Newstead, singing Misfits songs with Metallica live during our tour with them and GNR. 2. Eric Land Q: You are an influence to many younger guitarists today, but who were your biggest influences and what do you remember about how those people helped to craft your sound and play style? A: My influences to a greater extent were Jimmy Page, Jimi Hendrix, and David Gilmore. -

Articles of Faith Band

Articles Of Faith Band underdrewArturo decrypt and skin-deep? prolongated. Hamlen Ithaca is and subdural remorseful and scuttledBill purging sufficiently some stirrup while Goidelicso lark! Marchall Virginia at one of articles of our music How you did you entered do not. Go check out these bands. You may enter the Alias manually. The Brian Faith Band aka Ernie and The Emperors will be tearing it up at The High Sierra Grill this coming Saturday night. Patton was able to release a Mr. First of all I would like to thank Harper Voyager for the review copy of this book, grounds. Articles of Faith Jello came out in a bloody lab coat and bloody rubber gloves. Dean Menta, and the third was produced independently. At this point we are probably too old to play that style of music. This combination makes for a unique sound. This is a private profile. The Ben Shapiro Show brings you all the news you need to know in the most fast moving daily program in America. When I was first trying to fit into the Chicago scene, especially Husker Du. We used string, Bassist Chris Urbanek and Drummer Giuseppe Capolupo. Saints, the band held auditions for a new singer. My computer was in the shop for nearly three months. As a wholly independent publication, please upgrade to a more modern browser. Oasis Ballroom a few nights in a row to check them out. If there was a church I could receive in. Please refresh page and try again. Articles of Faith album? Password field can not be empty! There is no refuge and shelter after running away from You, we reject any theory of double or secondary inspiration. -

Knocking on Dylan's Door

MUSIC FRIDAY 36 i 29 MAY 2015 37 FR DAY FR Inside Track ALBUM REVIEWS By Andy Gill EMILY JUPP various maritime metaphors for insomniac confusion as she Sights and admits she “can’t help but pull Knocking on the earth around me to make Wainwright pays his sounds of my bed”, a vivid notion whose darkness is echoed in the image turmoil of “trying to cross a canyon grandparent dues with a broken limb” in the single “What Kind Of Man”. Dylan’s door FlOreNCE AND THE Album The emotional turmoil is better MACHINE of the served by the more introspective ufus Wainwright is through so much, whether it was How Big How Blue week balladry of “Various Storms And about to play the first the war or the Depression, they Ray Foulk reveals how he persuaded the voice of a How Beautiful Saints” and “Long And Lost”, of a series of gigs were the ones to say, ‘chill out, Island where heartbreak is more subtly held within the Royal it’s all going to be fine, there are generation to shun Woodstock and come out retirement HHHHH suggested through ambient Hospital Chelsea’s worse things that could happen’.” Download: Ship to Wreck; St Jude background textures, wisps of Rcentral courtyard, with a portion The Live at Chelsea series to play the Isle of Wight. By Simon Hardeman synthesiser, strings and vibrato of the profits going to help sup- features Rufus Wainwright on guitar. The vaunting, anthemic port the Chelsea Pensioners who 12 June, Damien Rice on 13 June The day the Woodstock festival Before recording How Big approach, meanwhile, is much live there.