LEARN and EARN How Schools Prepared Students to Seek out Decent Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section II: Periodic Report on the State of Conservation of the Ban Chiang

Thailand National Periodic Report Section II State of Conservation of Specific World Heritage Properties Section II: State of Conservation of Specific World Heritage Properties II.1 Introduction a. State Party Thailand b. Name of World Heritage property Ban Chiang Archaeological Site c. Geographical coordinates to the nearest second North-west corner: Latitude 17º 24’ 18” N South-east corner: Longitude 103º 14’ 42” E d. Date of inscription on the World Heritage List December 1992 e. Organization or entity responsible for the preparation of the report Organization (s) / entity (ies): Ban Chiang National Museum, Fine Arts Department - Person (s) responsible: Head of Ban Chiang National Museum, Address: Ban Chiang National Museum, City and Post Code: Nhonghan District, Udonthanee Province 41320 Telephone: 66-42-208340 Fax: 66-42-208340 Email: - f. Date of Report February 2003 g. Signature on behalf of State Party ……………………………………… ( ) Director General, the Fine Arts Department 1 II.2 Statement of significance The Ban Chiang Archaeological Site was granted World Heritage status by the World Heritage Committee following the criteria (iii), which is “to bear a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared ”. The site is an evidence of prehistoric settlement and culture while the artifacts found show a prosperous ancient civilization with advanced technology which had evolved for 5,000 years, such as rice farming, production of bronze and metal tools, and the production of pottery which had its own distinctive characteristics. The prosperity of the Ban Chiang culture also spread to more than a hundred archaeological sites in the Northeast of Thailand. -

A Practical Approach Toward Sustainable Development

A PRACTICAL APPROACH TOWARD SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT THAILAND’S SUFFICIENCY ECONOMY PHILOSOPHY A PRACTICAL APPROACH TOWARD SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT THAILAND’S SUFFICIENCY ECONOMY PHILOSOPHY TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Foreword 32 Goal 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure 6 SEP at a Glance TRANSFORMING INDUSTRY THROUGH CREATIVITY 8 An Introduction to the Sufficiency 34 Goal 10: Reduced Inequalities Economy Philosophy A PEOPLE-CENTERED APPROACH TO EQUALITY 16 Goal 1: No Poverty 36 Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and THE SEP STRATEGY FOR ERADICATING POVERTY Communities SMARTER, MORE INCLUSIVE URBAN DEVELOPMENT 18 Goal 2: Zero Hunger SEP PROMOTES FOOD SECURITY FROM THE ROOTS UP 38 Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production 20 Goal 3: Good Health and Well-being SEP ADVOCATES ETHICAL, EFFICIENT USE OF RESOURCES AN INCLUSIVE, HOLISTIC APPROACH TO HEALTHCARE 40 Goal 13: Climate Action 22 Goal 4: Quality Education INSPIRING SINCERE ACTION ON CLIMATE CHANGE INSTILLING A SUSTAINABILITY MINDSET 42 Goal 14: Life Below Water 24 Goal 5: Gender Equality BALANCED MANAGEMENT OF MARINE RESOURCES AN EGALITARIAN APPROACH TO EMPOWERMENT 44 Goal 15: Life on Land 26 Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation SEP ENCOURAGES LIVING IN HARMONY WITH NATURE A SOLUTION TO THE CHALLENGE OF WATER SECURITY 46 Goal 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions 28 Goal 7: Affordable and Clean Energy A SOCIETY BASED ON VIRTUE AND INTEGRITY EMBRACING ALTERNATIVE ENERGY SOLUTIONS 48 Goal 17: Partnerships for the Goals 30 Goal 8: Decent Work and FORGING SEP FOR SDG PARTNERSHIPS Economic Growth SEP BUILDS A BETTER WORKFORCE 50 Directory 2 3 FOREWORD In September 2015, the Member States of the United Nations resilience against external shocks; and collective prosperity adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, comprising through strengthening communities from within. -

• Ceramics from Muang Phan, Chiang Rai Province

CERAMICS FROM MUANG PHAN, CHIANG RAI PROVINCE by John N. Miksic* The ceramic tradition of northern Thailand bas been a subject of interest to art historians and archeologists, among others, for some time. The development of ceramic technology and products, including high-fired stonewares, is closely linked to the political development of the northern Thai states. The warfare and unstable economic conditions of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries A.D., consequent on • the struggles among several Thai kingdoms, are clearly correlated with the end of ceramic manufacture at the Sawankhalok and Sukbothai kilns. A number of kilns in the provinces of Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai and Lampang seem to have been built at that time, perhaps by potters who were seeking refuge from Ayutthayan invaders (Kraisri 1960: 18)2• Eventually it may be possible to write a comprehensive analysis of the development of Thai ceramics before and after the decline of Sukhothai influence in the late fourteenth ceo tury. It may be assumed that the political events of the time played nearly as important a role in shaping ceramic development as did the hands of the potters themselves. A clear picture of the course of ceramic development in the region, * Department of Anthropology, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 1485 3, USA. 1. The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Mr. Edward DeBruyn, who took the photographs which accompany this article, and of Miss Cynthia Mason, who made the drawings. The author is also indebted to Mr. Dean Frasche, Dr. Barbara Harrisson, Dr. Stanley J. O'Connor, and Dr. -

Lifestyle and Health Care of the Western Husbands in Kumphawapi District, Udon Thani Province,Thailand

7th International Conference on Humanities and Social Sciences “ASEAN 2015: Challenges and Opportunities” (Proceedings) Lifestyle and Health Care of the Western Husbands in Kumphawapi District, Udon Thani Province,Thailand 1. Mrs.Rujee Charupash, M.A. (Sociology), B.sc. (Nursing), Sirindhron College of Public Health, Khon Kaen. (Lecturer), [email protected] Abstract This qualitative research aims to study lifestyle and health care of Western husbands who married Thai wives and live in Kumphawapi District, Udon Thani Province. Five samples were purposively selected and primary qualitative data were collected through non-participant observations and in-depth interviews. The data was reviewed by Methodological Triangulation; then, the Typological Analysis was presented descriptively. Results: 1) Lifestyle of the Western husbands: In daily life, they had low cost of living in the villages and lived on pensions or savings that are only sufficient. Accommodation and environmental conditions, such as mothers’ modern western facilities for their convenience and overall surroundings are neat and clean. 2) Health care: the Western husbands who have diabetes, hypertension and heart disease were looked after by Thai wives to maintain dietary requirements of the disease. Self- treatment occurred via use of the drugstore or the local private clinic for minor illnesses. If their symptoms were severe or if they needed a checkup, they used the services of a private hospital in Udon Thani Province. They used their pension and savings for medical treatments. If a treatment expense exceeded their budget, they would go back to their own countries. Recommendations: The future study should focus on official Thai wives whose elderly Western husbands have underlying chronic diseases in order to analyze their use of their health care services, welfare payments for medical expenses and how the disbursement system of Thailand likely serves elderly citizens from other countries. -

Smallholders and Forest Landscape Restoration in Upland Northern Thailand

102 International Forestry Review Vol.19(S4), 2017 Smallholders and forest landscape restoration in upland northern Thailand A. VIRAPONGSEa,b aMiddle Path EcoSolutions, Boulder, CO 80301, USA bThe Ronin Institute, Montclair, NJ 07043, USA Email: [email protected] SUMMARY Forest landscape restoration (FLR) considers forests as integrated social, environmental and economic landscapes, and emphasizes the produc- tion of multiple benefits from forests and participatory engagement of stakeholders in FLR planning and implementation. To help inform application of the FLR approach in upland northern Thailand, this study reviews the political and historical context of forest and land manage- ment, and the role of smallholders in forest landscape management and restoration in upland northern Thailand. Data were collected through a literature review, interviews with 26 key stakeholders, and three case studies. Overall, Thai policies on socioeconomics, forests, land use, and agriculture are designed to minimize smallholders’ impact on natural resources, although more participatory processes for land and forest management (e.g. community forests) have been gaining some traction. To enhance the potential for FLR success, collaboration processes among upland forest stakeholders (government, NGOs, industry, ethnic minority smallholders, lowland smallholders) must be advanced, such as through innovative communication strategies, integration of knowledge systems, and most importantly, by recognizing smallholders as legitimate users of upland forests. Keywords: North Thailand, smallholders, forest management, upland, land use Politique forestière et utilisation de la terre par petits exploitants dans les terres hautes de la Thaïlande du nord A. VIRAPONGSE Cette étude cherche à comprendre le contexte politique de la gestion forestière dans les terres hautes de la Thaïlande du nord, et l’expérience qu’ont les petits exploitants de ces politiques. -

Department of Social Development and Welfare Ministry of Social

OCT SEP NOV AUG DEC JUL JAN JUN FEB MAY MAR APR Department of Social Development and Welfare Ministry of Social Development and Human Security ISBN 978-616-331-053-8 Annual Report 2015 y t M i r i u n c is e t S ry n o a f m So Hu ci d al D an evelopment Department of Social Development and Welfare Annual Report 2015 Department of Social Development and Welfare Ministry of Social Development and Human Security Annual Report 2015 2015 Preface The Annual Report for the fiscal year 2015 was prepared with the aim to disseminate information and keep the general public informed about the achievements the Department of Social Development and Welfare, Ministry of Social Development and Human Security had made. The department has an important mission which is to render services relating to social welfare, social work and the promotion and support given to local communities/authorities to encourage them to be involved in the social welfare service providing.The aim was to ensure that the target groups could develop the capacity to lead their life and become self-reliant. In addition to capacity building of the target groups, services or activities by the department were also geared towards reducing social inequality within society. The implementation of activities or rendering of services proceeded under the policy which was stemmed from the key concept of participation by all concerned parties in brainstorming, implementing and sharing of responsibility. Social development was carried out in accordance with the 4 strategic issues: upgrading the system of providing quality social development and welfare services, enhancing the capacity of the target population to be well-prepared for emerging changes, promoting an integrated approach and enhancing the capacity of quality networks, and developing the organization management towards becoming a learning organization. -

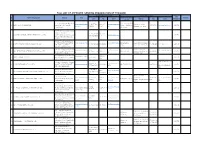

FULL LIST of APPROVED SENDING ORGANIZATION of THAILAND Approved Person in Charge of Training Contact Point in Japan Date No

FULL LIST OF APPROVED SENDING ORGANIZATION OF THAILAND Approved Person in charge of Training Contact Point in Japan date No. Name of Organization Address URL Name of Person in Remarks name TEL Email Address TEL Email (the date of Charge receipt) 10th ft. Social security., Ministry of Office of Labour Affair https://www.doe.go.th MR. KHATTIYA +662 245 [email protected] 3-14-6 kami - Osaki, 1 DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT Labour Mitr-Maitri Road, Din- in Japan (Mr.Saichon 03-5422-7014 [email protected] 2019/7/2 /overseas PANDECH 6708-9 om Shinagawa - ku Tokyo Daeng Bangkok Akanitvong) 259/333 2ND Floor Yangyuenwong Building, Sukhumvit 71 MR. PASSAPONG (66)-2-391- 2 J.J.S. BANGKOK DEVELOPMENT & MANPOWER CO., LTD. Road,Phrakhanongnua Sub-district, - [email protected] 2019/7/2 YANGYUENWONG 3499 Wattana District, Bangkok 10110 Thailand No.7,1ST FLOOR, SOI NAKNIWAT 57, NAKNIWAT ROAD, LADPRAO www.linkproplacement. [email protected] Ms. Suwutjittra Tokyo, Adachi Ku, Higashi 3 LINKPRO INTERNATIONAL PLACEMENT CO., LTD. MR. Korn Sakajai 080-6113525 090-7945-2494 [email protected] 2019/7/2 SUB-DISTRICT, LADPRAO net om Nawilai Ayase 1-15-19-102 Room DISTRICT, BANGKOK 10230 293/1,Mu 15,Nang-Lae Sub-district, 247-0071 Tamagawa, www.ainmanpower.co [email protected] [email protected] 4 ASIA INTERNATIONAL NETWORK MANPOWER CO., LTD. Muang Chiangrai District, Chiangrai Ms. Mayuree Jina 0918599777 Mr. Shoichi Saho Kamakura City, Kanagawa 080-3449-1607 2019/7/2 m .th h Province 57100 Thailand Prefecture, Japan 163/1 Nuanchan Rd,Nuanchan Sub- www.vincplacement.co +662 735 5 VINC PLACEMENT CO., LTD. -

Open Sangpenchan Msthesis.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of Geography CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS ON CASSAVA PRODUCTION IN NORTHEASTERN THAILAND A Thesis in Geography by Ratchanok Sangpenchan 2009 Ratchanok Sangpenchan Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2009 ii The thesis of Ratchanok Sangpenchan was reviewed and approved* by the following: Amy Glasmeier Professor of Geography Thesis Advisor William E. Easterling Professor of Geography Karl Zimmerer Head of the Department of Geography *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Analyses conducted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007) suggest that some regions of Southeast Asia will begin to experience warmer temperatures due to elevated CO2 concentrations. Since the projected change is expected to affect the agricultural sector, especially in the tropical climate zones, it is important to examine possible changes in crop yields and their bio-physiological responses to future climate conditions in these areas. This study employed a climate impact assessment to evaluate potential cassava root crop production in marginal areas of Northeast Thailand, using climate change projected by the CSIRO-Mk3 model for 2009–2038. The EPIC (Erosion Productivity Impact Calculator) crop model was then used to simulate cassava yield according to four scenarios based on combinations of CO2 fertilization effects scenarios (current CO2 level and 1% per year increase) and agricultural practice scenarios (with current practices and assumed future practices). Future practices are the result of assumed advances in agronomic technology that are likely to occur irrespective of climate change. They are not prompted by climate change per se, but rather by the broader demand for higher production levels. -

Transnational Economic Connectivity of the Vietnamese

Transnational Economic Connectivity of the Vietnamese Diaspora Community in Udon Thani Province, Thailand: Mirroring the ASEAN Economic Community 137 Transnational Economic Connectivity of the Introduction The transnational perspective in migration studies has gained popularity Vietnamese Diaspora Community in over the past two decades. Transnationalism is perceived as “multiple Udon Thani Province, Thailand: Mirroring ties and interactions linking people or institutions across the borders of 1 nation-states” (Vertovec, 1999: 447). Portes et al. (1999) categorized the ASEAN Economic Community three major forms of transnationalism: economic, political, and socio-cultural. Transnationalism is prevalent among diaspora groups Nguyen Thi Tu Anh whose consciousness is embedded in trans-state networks. The target Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand group of this research is the Vietnamese diaspora community settled in Email: [email protected] Udon Thani province, in the northeastern region (also known as Isan) Received: December 15, 2020 of Thailand. My work draws upon the idea that the construction of Revised: February 19, 2021 trans-border networks is a major activity conducted by “an ethno- Accepted: March 10, 2021 national diaspora” who “regard themselves as of the same ethno-national Abstract origin and permanently reside as minorities in one or several host This article is based on research concerning transnational economic connectivity countries” (Sheffer, 2003: 9, 10). established by the Vietnamese diaspora community in Udon Thani province in The use of the term “Vietnamese diaspora” in this study refers northeastern Thailand, a topic that has not yet received sufficient academic to those who hold Thai citizenship, have permanently settled in Udon attention. -

MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received Bom 9 to 14 May 1980 — Notifications Reçues Du 9 Au 14 Mai 1980 C Cases — Cas

Wkty Epldem. Bec.: No. 20 -16 May 1980 — 150 — Relevé éptdém. hebd : N° 20 - 16 mal 1980 Kano State D elete — Supprimer: Bimi-Kudi : General Hospital Lagos State D elete — Supprimer: Marina: Port Health Office Niger State D elete — Supprimer: Mima: Health Office Bauchi State Insert — Insérer: Tafawa Belewa: Comprehensive Rural Health Centre Insert — Insérer: Borno State (title — titre) Gongola State Insert — Insérer: Garkida: General Hospital Kano State In se rt— Insérer: Bimi-Kudu: General Hospital Lagos State Insert — Insérer: Ikeja: Port Health Office Lagos: Port Health Office Niger State Insert — Insérer: Minna: Health Office Oyo State Insert — Insérer: Ibadan: Jericho Nursing Home Military Hospital Onireke Health Office The Polytechnic Health Centre State Health Office Epidemiological Unit University of Ibadan Health Services Ile-Ife: State Hospital University of Ife Health Centre Ilesha: Health Office Ogbomosho: Baptist Medical Centre Oshogbo : Health Office Oyo: Health Office DISEASES SUBJECT TO THE REGULATIONS — MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received bom 9 to 14 May 1980 — Notifications reçues du 9 au 14 mai 1980 C Cases — Cas ... Figures not yet received — Chiffres non encore disponibles D Deaths — Décès / Imported cases — Cas importés P t o n r Revised figures — Chifircs révisés A Airport — Aéroport s Suspect cases — Cas suspects CHOLERA — CHOLÉRA C D YELLOW FEVER — FIÈVRE JAUNE ZAMBIA — ZAMBIE 1-8.V Africa — Afrique Africa — Afrique / 4 0 C 0 C D \ 3r 0 CAMEROON. UNITED REP. OF 7-13JV MOZAMBIQUE 20-26J.V CAMEROUN, RÉP.-UNIE DU 5 2 2 Asia — Asie Cameroun Oriental 13-19.IV C D Diamaré Département N agaba....................... î 1 55 1 BURMA — BIRMANIE 27.1V-3.V Petté ........................... -

The Model of Religious Education Management of Monks in Udon Thani Province

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education Vol.12 No. 8 (2021), 2492-2498 Research Article The model of religious education management of monks in Udon Thani province a b Phramahasuphon Supalo (Sukda) Pannawat Ngamsaeng Assoc. Prof. Dr. Phramaha Mit Thapanyao a ,bFaculty of Buddhist Dependent, Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Thailand Email:[email protected], [email protected] *Corresponding Author e-mail: [email protected] Article History: Received: 10 January 2021; Revised: 12 February 2021; Accepted: 27 March 2021; Published online: 20 April 2021 Abstract: The purposes of this research were 1) to study religious education management of monks in Buddhism, 2) to study religious education management of monks in Udon Thani Province, and 3) to propose the model of religious education management of monks in Udon Thani Province. This research was qualitative research. The data were collected from primary sources and secondary sources and interview. The descriptive analysis was used to analyze. Results found that for religious education management of monks in Buddhism, it aimed to Sikkha (the threefold learning) in the Buddha era. Buddha’s doctrine was said that it was the principle of the conduct and Buddhism dissemination. Later, it was divided into Gantha-dhura (burden of study) and Vipassana-dhura (burden of insight development). Since Buddhism has been spread to Thailand, religious education management of monks has evolved respectively to the present. Religious education management was divided into Dhamma division, Pali division and general education division. Religious education management of monks in Udon Thani province could be divided into three divisions 1) Dhamma Studies consisting of Dhamma curriculum and Dhamma studies, Sunday Buddhism curriculum, 2) Pali division consisting of Pali curriculum and Pali studies. -

It's Dusk in the Jungle of Northern Thailand's Chiang Rai Province

Wildest Drea s IN SOUTHEAST ASIA’S GOLDEN TRIANGLE, AN ADVENTURE CAMP SHOWS HOW TOURISM CAN HELP ENDANGERED ELEPHANTS. By Joel Centano It’s dusk in the jungle of northern Thailand’s Chiang Rai province. A symphony of cicadas plays in surround-sound as fireflies flare in the jasmine-scented air. I’m seated in an outdoor sala, preparing to tuck into a three-course Thai feast, watching as my plus-size dinner companions approach through the gloaming. Moving closer, their colossal forms take shape in the lamplight. They breathe in my scent as a form of greeting, flutter their ears like butterfly wings, and then let it be known that it’s time to eat. Long, strong, prehensile trunks sinuate and stretch, snatching up liberal servings of sugarcane from my outstretched hands. 30 VIRTUOSO TRAVELER | VIRTUOSO.COM Wild and scenic: Views from the Anantara Golden Triangle Elephant Camp & Resort. (MAHOUT AND LEAF) JOEL CENTANO, (MAHOUT AND LEAF) JOEL CENTANO, NOUN PROJECT KARAVDIC/THE (ELEPHANT ICON) ADRIJAN DECEMBER 2014 31 Also Consider Explore the Golden Triangle beyond Anantara’s elephant camp through its collection of excursions. Travel advisors can help tailor your experience to fit your interests, from touring temples to perfecting pad thai. Set foot in three countries on a guided daylong journey that visits Phra Jow La Keng monastery (shown above) in Myanmar, thirteenth-century temples in the Thai town of Chiang Saen, and the market on the Laotian island of Done Clockwise from top: Pachyderm parade, chef Paitoon prepares a breakfast Xao. A bonus: A longtail boat ride up picnic at Chiang Saen’s Wat Pa Sak, and sala dining at the resort.