Understanding Healthy Aging in Isan-Thai Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section II: Periodic Report on the State of Conservation of the Ban Chiang

Thailand National Periodic Report Section II State of Conservation of Specific World Heritage Properties Section II: State of Conservation of Specific World Heritage Properties II.1 Introduction a. State Party Thailand b. Name of World Heritage property Ban Chiang Archaeological Site c. Geographical coordinates to the nearest second North-west corner: Latitude 17º 24’ 18” N South-east corner: Longitude 103º 14’ 42” E d. Date of inscription on the World Heritage List December 1992 e. Organization or entity responsible for the preparation of the report Organization (s) / entity (ies): Ban Chiang National Museum, Fine Arts Department - Person (s) responsible: Head of Ban Chiang National Museum, Address: Ban Chiang National Museum, City and Post Code: Nhonghan District, Udonthanee Province 41320 Telephone: 66-42-208340 Fax: 66-42-208340 Email: - f. Date of Report February 2003 g. Signature on behalf of State Party ……………………………………… ( ) Director General, the Fine Arts Department 1 II.2 Statement of significance The Ban Chiang Archaeological Site was granted World Heritage status by the World Heritage Committee following the criteria (iii), which is “to bear a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared ”. The site is an evidence of prehistoric settlement and culture while the artifacts found show a prosperous ancient civilization with advanced technology which had evolved for 5,000 years, such as rice farming, production of bronze and metal tools, and the production of pottery which had its own distinctive characteristics. The prosperity of the Ban Chiang culture also spread to more than a hundred archaeological sites in the Northeast of Thailand. -

(Unofficial Translation) Order of the Centre for the Administration of the Situation Due to the Outbreak of the Communicable Disease Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) No

(Unofficial Translation) Order of the Centre for the Administration of the Situation due to the Outbreak of the Communicable Disease Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) No. 1/2564 Re : COVID-19 Zoning Areas Categorised as Maximum COVID-19 Control Zones based on Regulations Issued under Section 9 of the Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situations B.E. 2548 (2005) ------------------------------------ Pursuant to the Declaration of an Emergency Situation in all areas of the Kingdom of Thailand as from 26 March B.E. 2563 (2020) and the subsequent 8th extension of the duration of the enforcement of the Declaration of an Emergency Situation until 15 January B.E. 2564 (2021); In order to efficiently manage and prepare the prevention of a new wave of outbreak of the communicable disease Coronavirus 2019 in accordance with guidelines for the COVID-19 zoning based on Regulations issued under Section 9 of the Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situations B.E. 2548 (2005), by virtue of Clause 4 (2) of the Order of the Prime Minister No. 4/2563 on the Appointment of Supervisors, Chief Officials and Competent Officials Responsible for Remedying the Emergency Situation, issued on 25 March B.E. 2563 (2020), and its amendments, the Prime Minister, in the capacity of the Director of the Centre for COVID-19 Situation Administration, with the advice of the Emergency Operation Center for Medical and Public Health Issues and the Centre for COVID-19 Situation Administration of the Ministry of Interior, hereby orders Chief Officials responsible for remedying the emergency situation and competent officials to carry out functions in accordance with the measures under the Regulations, for the COVID-19 zoning areas categorised as maximum control zones according to the list of Provinces attached to this Order. -

The Puzzling Absence of Ethnicity-Based Political Cleavages in Northeastern Thailand

Proud to be Thai: The Puzzling Absence of Ethnicity- Based Political Cleavages in Northeastern Thailand Jacob I. Ricks Abstract Underneath the veneer of a homogenous state-approved Thai ethnicity, Thailand is home to a heterogeneous population. Only about one-third of Thailand’s inhabitants speak the national language as their mother tongue; multiple alternate ethnolinguistic groups comprise the remainder of the population, with the Lao in the northeast, often called Isan people, being the largest at 28 percent of the population. Ethnic divisions closely align with areas of political party strength: the Thai Rak Thai Party and its subsequent incarnations have enjoyed strong support from Isan people and Khammuang speakers in the north while the Democrat Party dominates among the Thai- and Paktay-speaking people of the central plains and the south. Despite this confluence of ethnicity and political party support, we see very little mobilization along ethnic cleavages. Why? I argue that ethnic mobilization remains minimal because of the large-scale public acceptance and embrace of the government-approved Thai identity. Even among the country’s most disadvantaged, such as Isan people, support is still strong for “Thai-ness.” Most inhabitants of Thailand espouse the mantra that to Copyright (c) Pacific Affairs. All rights reserved. be Thai is superior to being labelled as part of an alternate ethnic group. I demonstrate this through the application of large-scale survey data as well as a set of interviews with self-identified Isan people. The findings suggest that the Thai state has successfully inculcated a sense of national identity Delivered by Ingenta to IP: 192.168.39.151 on: Sat, 25 Sep 2021 22:54:19 among the Isan people and that ethnic mobilization is hindered by ardent nationalism. -

Ratchaburi Ratchaburi Ratchaburi

Ratchaburi Ratchaburi Ratchaburi Dragon Jar 4 Ratchaburi CONTENTS HOW TO GET THERE 7 ATTRACTIONS 9 Amphoe Mueang Ratchaburi 9 Amphoe Pak Tho 16 Amphoe Wat Phleng 16 Amphoe Damnoen Saduak 18 Amphoe Bang Phae 21 Amphoe Ban Pong 22 Amphoe Photharam 25 Amphoe Chom Bueng 30 Amphoe Suan Phueng 33 Amphoe Ban Kha 37 EVENTS & FESTIVALS 38 LOCAL PRODUCTS & SOUVENIRS 39 INTERESTING ACTIVITIS 43 Cruising along King Rama V’s Route 43 Driving Route 43 Homestay 43 SUGGEST TOUR PROGRAMMES 44 TRAVEL TIPS 45 FACILITIES IN RATCHABURI 45 Accommodations 45 Restaurants 50 Local Product & Souvenir Shops 54 Golf Courses 55 USEFUL CALLS 56 Floating Market Ratchaburi Ratchaburi is the land of the Mae Klong Basin Samut Songkhram, Nakhon civilization with the foggy Tanao Si Mountains. Pathom It is one province in the west of central Thailand West borders with Myanmar which is full of various geographical features; for example, the low-lying land along the fertile Mae Klong Basin, fields, and Tanao Si Mountains HOW TO GET THERE: which lie in to east stretching to meet the By Car: Thailand-Myanmar border. - Old route: Take Phetchakasem Road or High- From legend and historical evidence, it is way 4, passing Bang Khae-Om Noi–Om Yai– assumed that Ratchaburi used to be one of the Nakhon Chai Si–Nakhon Pathom–Ratchaburi. civilized kingdoms of Suvarnabhumi in the past, - New route: Take Highway 338, from Bangkok– from the reign of the Great King Asoka of India, Phutthamonthon–Nakhon Chai Si and turn into who announced the Lord Buddha’s teachings Phetchakasem Road near Amphoe Nakhon through this land around 325 B.C. -

A Practical Approach Toward Sustainable Development

A PRACTICAL APPROACH TOWARD SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT THAILAND’S SUFFICIENCY ECONOMY PHILOSOPHY A PRACTICAL APPROACH TOWARD SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT THAILAND’S SUFFICIENCY ECONOMY PHILOSOPHY TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Foreword 32 Goal 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure 6 SEP at a Glance TRANSFORMING INDUSTRY THROUGH CREATIVITY 8 An Introduction to the Sufficiency 34 Goal 10: Reduced Inequalities Economy Philosophy A PEOPLE-CENTERED APPROACH TO EQUALITY 16 Goal 1: No Poverty 36 Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and THE SEP STRATEGY FOR ERADICATING POVERTY Communities SMARTER, MORE INCLUSIVE URBAN DEVELOPMENT 18 Goal 2: Zero Hunger SEP PROMOTES FOOD SECURITY FROM THE ROOTS UP 38 Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production 20 Goal 3: Good Health and Well-being SEP ADVOCATES ETHICAL, EFFICIENT USE OF RESOURCES AN INCLUSIVE, HOLISTIC APPROACH TO HEALTHCARE 40 Goal 13: Climate Action 22 Goal 4: Quality Education INSPIRING SINCERE ACTION ON CLIMATE CHANGE INSTILLING A SUSTAINABILITY MINDSET 42 Goal 14: Life Below Water 24 Goal 5: Gender Equality BALANCED MANAGEMENT OF MARINE RESOURCES AN EGALITARIAN APPROACH TO EMPOWERMENT 44 Goal 15: Life on Land 26 Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation SEP ENCOURAGES LIVING IN HARMONY WITH NATURE A SOLUTION TO THE CHALLENGE OF WATER SECURITY 46 Goal 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions 28 Goal 7: Affordable and Clean Energy A SOCIETY BASED ON VIRTUE AND INTEGRITY EMBRACING ALTERNATIVE ENERGY SOLUTIONS 48 Goal 17: Partnerships for the Goals 30 Goal 8: Decent Work and FORGING SEP FOR SDG PARTNERSHIPS Economic Growth SEP BUILDS A BETTER WORKFORCE 50 Directory 2 3 FOREWORD In September 2015, the Member States of the United Nations resilience against external shocks; and collective prosperity adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, comprising through strengthening communities from within. -

Lifestyle and Health Care of the Western Husbands in Kumphawapi District, Udon Thani Province,Thailand

7th International Conference on Humanities and Social Sciences “ASEAN 2015: Challenges and Opportunities” (Proceedings) Lifestyle and Health Care of the Western Husbands in Kumphawapi District, Udon Thani Province,Thailand 1. Mrs.Rujee Charupash, M.A. (Sociology), B.sc. (Nursing), Sirindhron College of Public Health, Khon Kaen. (Lecturer), [email protected] Abstract This qualitative research aims to study lifestyle and health care of Western husbands who married Thai wives and live in Kumphawapi District, Udon Thani Province. Five samples were purposively selected and primary qualitative data were collected through non-participant observations and in-depth interviews. The data was reviewed by Methodological Triangulation; then, the Typological Analysis was presented descriptively. Results: 1) Lifestyle of the Western husbands: In daily life, they had low cost of living in the villages and lived on pensions or savings that are only sufficient. Accommodation and environmental conditions, such as mothers’ modern western facilities for their convenience and overall surroundings are neat and clean. 2) Health care: the Western husbands who have diabetes, hypertension and heart disease were looked after by Thai wives to maintain dietary requirements of the disease. Self- treatment occurred via use of the drugstore or the local private clinic for minor illnesses. If their symptoms were severe or if they needed a checkup, they used the services of a private hospital in Udon Thani Province. They used their pension and savings for medical treatments. If a treatment expense exceeded their budget, they would go back to their own countries. Recommendations: The future study should focus on official Thai wives whose elderly Western husbands have underlying chronic diseases in order to analyze their use of their health care services, welfare payments for medical expenses and how the disbursement system of Thailand likely serves elderly citizens from other countries. -

The Management Style of Cultural Tourism in the Ancient Monuments of Lower Central Thailand

Asian Social Science; Vol. 9, No. 13; 2013 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Management Style of Cultural Tourism in the Ancient Monuments of Lower Central Thailand Wasana Lerkplien1, Chamnan Rodhetbhai1 & Ying Keeratiboorana1 1 The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham, Thailand Correspondence: Wasana Lerkplien, 379 Tesa Road, Prapratone Subdistrict, Mueang District, Nakhon Pathom 73000, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] Received: May 22, 2013 Accepted: July 4, 2013 Online Published: September 29, 2013 doi:10.5539/ass.v9n13p112 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v9n13p112 Abstract Cultural tourism is a vital part of the Thai economy, without which the country would have a significantly reduced income. Key to the cultural tourism business in Thailand is the ancient history that is to be found throughout the country in the form of monuments and artifacts. This research examines the management of these ancient monuments in the lower central part of the country. By studying problems with the management of cultural tourism, the researchers outline a suitable model to increase its efficiency. For the attractions to continue to provide prosperity for the nation, it is crucial that this model is implemented to create a lasting and continuous legacy for the cultural tourism business. Keywords: management, cultural tourism, ancient monuments, central Thailand, conservation, efficiency 1. Introduction Tourism is an industry that can generate significant income for the country and, for many years, tourists have been the largest source of income for Thailand when compared to other areas. -

Department of Social Development and Welfare Ministry of Social

OCT SEP NOV AUG DEC JUL JAN JUN FEB MAY MAR APR Department of Social Development and Welfare Ministry of Social Development and Human Security ISBN 978-616-331-053-8 Annual Report 2015 y t M i r i u n c is e t S ry n o a f m So Hu ci d al D an evelopment Department of Social Development and Welfare Annual Report 2015 Department of Social Development and Welfare Ministry of Social Development and Human Security Annual Report 2015 2015 Preface The Annual Report for the fiscal year 2015 was prepared with the aim to disseminate information and keep the general public informed about the achievements the Department of Social Development and Welfare, Ministry of Social Development and Human Security had made. The department has an important mission which is to render services relating to social welfare, social work and the promotion and support given to local communities/authorities to encourage them to be involved in the social welfare service providing.The aim was to ensure that the target groups could develop the capacity to lead their life and become self-reliant. In addition to capacity building of the target groups, services or activities by the department were also geared towards reducing social inequality within society. The implementation of activities or rendering of services proceeded under the policy which was stemmed from the key concept of participation by all concerned parties in brainstorming, implementing and sharing of responsibility. Social development was carried out in accordance with the 4 strategic issues: upgrading the system of providing quality social development and welfare services, enhancing the capacity of the target population to be well-prepared for emerging changes, promoting an integrated approach and enhancing the capacity of quality networks, and developing the organization management towards becoming a learning organization. -

Factors Influencing Water Quality of Kwae-Om Canal, Samut Songkram Province

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 197 ( 2015 ) 916 – 921 7th World Conference on Educational Sciences, (WCES-2015), 05-07 February 2015, Novotel Athens Convention Center, Athens, Greece Factors Influencing Water Quality of Kwae-om Canal, Samut Songkram Province. Srisuwan Kaseamsawata*, Sivapan Choo – ina, Tatsanawalai Utaraskula, and Adisak b Chuangyham a Faculty of Sciences and Technology, Suan Sunandha Rajabhat University, 1 U-tong Nok Road, Dusit ,Bangkok, Thailand. 10300 b Bang Nang Li Sub-district, Amphawa District, Samut Songkram Province, Thailand Abstract This research was focus on factors affecting water quality in Kwae-om Canal in Bang Khonthi District, Samut Songkhram. The objectives were (1) to monitoring the quality of the source water, with discharged into the Kwae-om Canal Bang Khonthi District, (2) to study the relationship between the water quality and source of water pollutant, and to determine the factors that affect water quality. Water samples were collected from 41 points (for summer and rainy) and analyzed water quality according to standard methods. The results showed that the water quality does not meet the quality standards of surface water category 3 of the PCD. Seasonal effect on the amount of cadmium in the water. Water temperatures, pH, nitrogen in nitrate, copper, manganese and zinc compounds were met category 3 of the PCD. According to the factors of land use, dissolved oxygen, ammonia nitrogen, fecal coliform bacteria and total coliform bacteria did not meet the standard. © 20152015 The The Authors. Authors. Published Published by byElsevier Elsevier Ltd. LtdThis. is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (Peerhttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/-review under responsibility of Academic World). -

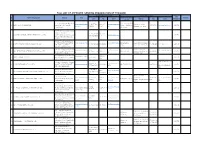

FULL LIST of APPROVED SENDING ORGANIZATION of THAILAND Approved Person in Charge of Training Contact Point in Japan Date No

FULL LIST OF APPROVED SENDING ORGANIZATION OF THAILAND Approved Person in charge of Training Contact Point in Japan date No. Name of Organization Address URL Name of Person in Remarks name TEL Email Address TEL Email (the date of Charge receipt) 10th ft. Social security., Ministry of Office of Labour Affair https://www.doe.go.th MR. KHATTIYA +662 245 [email protected] 3-14-6 kami - Osaki, 1 DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT Labour Mitr-Maitri Road, Din- in Japan (Mr.Saichon 03-5422-7014 [email protected] 2019/7/2 /overseas PANDECH 6708-9 om Shinagawa - ku Tokyo Daeng Bangkok Akanitvong) 259/333 2ND Floor Yangyuenwong Building, Sukhumvit 71 MR. PASSAPONG (66)-2-391- 2 J.J.S. BANGKOK DEVELOPMENT & MANPOWER CO., LTD. Road,Phrakhanongnua Sub-district, - [email protected] 2019/7/2 YANGYUENWONG 3499 Wattana District, Bangkok 10110 Thailand No.7,1ST FLOOR, SOI NAKNIWAT 57, NAKNIWAT ROAD, LADPRAO www.linkproplacement. [email protected] Ms. Suwutjittra Tokyo, Adachi Ku, Higashi 3 LINKPRO INTERNATIONAL PLACEMENT CO., LTD. MR. Korn Sakajai 080-6113525 090-7945-2494 [email protected] 2019/7/2 SUB-DISTRICT, LADPRAO net om Nawilai Ayase 1-15-19-102 Room DISTRICT, BANGKOK 10230 293/1,Mu 15,Nang-Lae Sub-district, 247-0071 Tamagawa, www.ainmanpower.co [email protected] [email protected] 4 ASIA INTERNATIONAL NETWORK MANPOWER CO., LTD. Muang Chiangrai District, Chiangrai Ms. Mayuree Jina 0918599777 Mr. Shoichi Saho Kamakura City, Kanagawa 080-3449-1607 2019/7/2 m .th h Province 57100 Thailand Prefecture, Japan 163/1 Nuanchan Rd,Nuanchan Sub- www.vincplacement.co +662 735 5 VINC PLACEMENT CO., LTD. -

Read This Article

INTEGRAL STUDY OF THE SILK ROADS ROADS OF DIALOGUE 21-22 JANUARY 1991. BANGKOK, THAILAND Document No. 15 Merchants, Merchandise, Markets: Archaeological Evidence in Thailand Concerning Maritime Trade Interaction Between Thailand and Other Countries Before the 16th A.D. Mrs. Amara Srisuchat 1 Merchants, Merchandise, Markets: Archaeological Evidence in Thailand Concerning Maritime Trade Interaction Between Thailand and Other Countries before the 16th A.D. Amara Srisuchat Abstract This article uses archeological evidence to indicate that humans on Thai soil had been engaged in maritime trade with other countries since prehistoric times. The inhabitants of settlements in this area already possessed a sophisticated culture and knowledge which made it possible for them to navigate sea-faring vessels, which took them on voyages and enabled them to establish outside contact before the arrival of navigators from abroad. Why then, were Thai sailors not well known to the outside world? This can partially be explained by the fact that they rarely travelled far from home as was the practice of Chinese and Arab soldiers. Furthermore, the availability of so wide a variety of resources in this region meant that there was little necessity to go so far afield in search of other, foreign commodities. Coastal settlements and ports were successfully developed to provide services, and markets were established with the local merchants who consequently become middlemen. Foreign technology was adapted to create industries which produced merchandises for export in accordance with the demand of the world market. At the same time, trading contacts with various countries had the effect of changing, to no small extent, the culture and society. -

LEARN and EARN How Schools Prepared Students to Seek out Decent Work

LEARN AND EARN How schools prepared students to seek out decent work 1 THE PROJECT’S OBJECTIVE: Teaching students entrepreneurial and vocational skills through actual income-earning enterprises and preparing them for a smoother school-to- work transition. Facilitating school-to work transition: Income generating in school-based activities and awareness raising THE INITIAL CHALLENGE: Research had revealed a large number of children in schools who combine education with hazardous work; they need to earn an income in order to stay in school or to help their family. But in the north-eastern Udon Thani province and the northern province of Chiang Rai, many students engage in work that has potential negative impact on their development, such as tapping rubber trees in the hours after midnight until dawn or working in markets at late hours. There was a need to convince them and their families they should do other work that allowed them to get the critical sleep that children need to develop appropriately. There also was a need to provide income-generating options to young students who were at risk of leaving school in order to work - the research indicated about 5,000 students in four districts of Udon Thani were verging on dropping out. Eliminating the Worst Forms of Child Labour in Thailand : Good Practices and Lessons Learned THE RESPONSE: Working children in agriculture, the service sector or in domestic labour were given opportunity to pursue recreational activities, non-formal education, career counselling, skills development and apprenticeships that suited their interests. THE PROCESS: The International Labour Organization’s International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour and its Project to Support National Action to Combat Child Labour and Its Worst Forms in Thailand (the ILO-IPEC project) worked with the Child and Youth Assembly of Udon Thani (CYA) to help teachers target 600 working or at-risk, students.