Making Your Workplace Smokefree a Decision Maker’S Guide Making Your Workplace Smokefree a Decision Maker’S Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctorate in Business Administration

A STUDY OF MARKETING STRATEGIES OF SELECTED TINY AND SMALL SCALE BAKERIES OF KOLKATA ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTORATE IN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION BY Atish Kumar Chattopadhyay Under the Guidanc* of Prof. Kaleem Mohammed Khu Dr. Anup Choadhnri Dean b Chairman Assaciate Dean Department of Business Administration The ICFAI Business School Faculty of Management Studies & Research The ICFAI University Atigarh MusDm University, Aligarh (iruiia) Kolkata (India) (Internal Advisor) (External Advisor) DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION FACULTY OF MANAGEMENT STUDIES AND RESEARCH ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INOIA) ^ 2005 ^yg^ Ai-' lit / li ' 1. Introduction In recent years there have been signs of substantial research interest in marketing practices of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) (Gillmore et. al, 2001; Blankson and Stokes, 2002; Hill, 2001; Siu, 2000; Siu et. al, 2004; Morrison, 2003; Lee et. al, 2001). Most of these studies have indicated the role of marketing to be critical in the sustainability of the small firms. In a recent study (Huang and Brown, 1999), the problems of sales and marketing were reported as important by 40 percent of the firms surveyed while other important factors reported were human resources (15 percent), general management (14 percent) and production / operations (9 percent) \ In India, a survey by the All India Management Association pointed out that among 872 SSI (Small Scale Industry) units in manufacturing, growth fell by 8.1 percent in 1998-2002. One of the main reasons cited by the units for not being able to do well was problems related to marketing (70 percent) (Jain, 2003). -

Fire District Faced with Deciding Fate of Private Nursery

Property of the Watertown Historical Society watertownhistoricalsociety.org M G Q •Si i"^! t'-i O Uowm Xtfmee CJ: Timely Coverage Of News In The Fastest Growing Community In Litehfield County Vol., 41 No. 49 SUBSCRIPTION PRICE $12.00 PER YEAR.. Car. Rt. P.S. PRICE 30 CENT'S Dec. II, 1986" Four Coaching Spots Fitted- By Board; Grant In Works Fire District Faced The Board of Education Monday Mis. .Rector,said the grant will be night approved four coaching ap- used to upgrade the electronics lab pointments during its final at the school. Some of the decade- regularly-scheduled meeting before old equipment is obsolete:,, while With Deciding Fate the Christmas holiday, some is no longer repairable. William. Yeager was named to .Board member Catherine Carney coach, the Watertown High School, spoke strongly in favor of the grant girls" varsity basketball learn for application, noting the Board pro- 1986-87' for a stipend of $1,640. He bably would have to improve the Of Private Nursery replaces longtime coach Marie equipment anyway at its own ex- Sampson. pense. Application deadline is Dec. Vivian Kirkfield's request for a. nursery at her Old Woodbury Road my 2-year-old will undermine the Sue Bavone will coach the girls" 31. day nursery special use exemption home before: moving to Scott integrity of the neighborhood."* Avenue. She is licensed, with the junior varsity team, for a $996 sti- The grant was developed, by Mrs. at her 74 Scott Ave. home has rais- .Mrs. Kirkfield, is licensed to care state. pend... Carol, Ann Brown, a WHS Rector in conjunction with Thomas ed some eyebrows in, the neigh- for six children. -

Type Category Description F Food and Beverage

The original source for data in this spreadsheet is a 2002 study for MassDEP by Draper/Lennon, Inc. titled Identification, Characterization, and Mapping of Food Waste and Food Waste Generators in Massachusetts . The final report from this study is available online at: http://www.mass.gov/dep/about/priorities/foodwast.doc. The data was updated in summer 2011 by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 1 office. This study identified large generators of food waste in Massachusetts, such as food processors, wholesalers, grocery stores, institutions, and large restaurants. It calculated estimated food waste generation, shown in tons per year (TPY) in column G, and mapped generator locations to facilitate planning of programs and facilities for capturing source separated organic materials for composting or other diversion. Note that waste generation estimates are not available for food and beverage manufacturers/processors and distributors due to the variability in these sectors. In some other cases, generation estimates are not available for other facilities when data needed to estimate generation is missing for that location. Facility Category Codes in column F marked TYPE show generator groupings in the report as follows: Type Category Description Food and Beverage F Manufacturers/Processors W Wholesale Distributors IH Institutions -Healthcare Facilities IS Institutions -Independent Schools IC Institutions -Colleges/Universities IP Institutions -Correctional Facilities C Resorts and Conference Facilities G Supermarkets and Grocery Stores R Restaurants Most of the columns in the spreadsheet are self‐explanatory. Columns H, I J, and K provide GIS mapping coordinates to assist in locating food waste generators. The Massachusetts State Plane coordinates found in the X_Coord and Y_Coord fields (Columns J and K) were derived by address‐ matching via Navteq Postal Villages. -

View Annual Report

Washington Trust Bancorp, Inc. 2002 Annual Report Washington Trust Bancorp, Inc. 2002 Annual Report Our Vision: To Be The Best Community Bank And Trust Company In New England Our Mission: Contents As an independent financial 2002 Financial Highlights...................................inside cover services company, we will provide the Corporate Highlights............................................inside cover highest value to our shareholders by: Letter to Shareholders .................................................one Acquisition of Phoenix New Markets ................................................................two Investment Management – 2000 Delivering superior service Business Banking .......................................................four to our customers, Phoenix Investment Management ............................eight Acquisition of First Bank and Trust Company – 2002 Providing financial and Trust & Investment Services..................................nine public service leadership in Personal Banking ........................................................ten Warwick Branch Opening – 2003 our communities, Consolidated Balance Sheets ....................................twelve Washington Trust Fostering a well-trained and Consolidated Statements of Income .......................thirteen Founded – 1800 highly motivated staff. Consolidated Statements of Changes in Shareholders’ Equity ..........................................fourteen Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows...................fifteen Independent Auditors’ Report -

S.K. Tangible Property List Dec 2014

$ 22,000.00 108 ROADHOUSE LLC 1464 KINGSTOWN ROAD PEACE DALE RI 02879-2198 PEACE DALE RI 02879-2198 $ 2,000.00 401 STUDIO 396 MAIN STREET WAKEFIELD RI 02879-7407 WAKEFIELD RI 02879-7407 $ 940,956.00 981 KINGS TOWN ROAD LLC C/O SCALLOP SHELL NURSING 981 KINGSTOWN ROAD WAKEFIELD RI 02879-3042 WAKEFIELD RI 02879-3042 $ 5,000.00 A & B FAMILY APPLIANCES C/O JIM BUCHANAN 446A MAIN STREET WAKEFIELD RI 02879 WAKEFIELD RI 02879 $ 6,000.00 A CAR CARRIER 2751 COMM O H PERRY HIGHWAY WAKEFIELD RI 02879-3955 WAKEFIELD RI 02879-3955 $ 16,000.00 A PLUS LANDSCAPING INC 1104 MOORESFIELD ROAD WAKEFIELD RI 02879-2041 WAKEFIELD RI 02879-2041 $ 500.00 AAAA DAVES CHIMNEY C/O DAVID GEER 189 HIGHLAND AVENUE WAKEFIELD RI 02879-3404 WAKEFIELD RI 02879-3404 $ 2,000.00 AAAHHH QUALITY CLEANING SERVIC C/O MARK NEVITT PO BOX 5431 WAKEFIELD RI 02880-5431 WAKEFIELD RI 02880-5431 $ 22,080.00 ABBY'S ATTIC 254 ROBINSON STREET WAKEFIELD RI 02879-3579 WAKEFIELD RI 02879-3579 $ 7,500.00 ABSOLUT MARKET & SMOKE SHOP 100 FORTIN ROAD KINGSTON RI 02881-1440 KINGSTON RI 02881-1440 $ 10,987.00 ADORNMENT 82 KIMBERLEY DRIVE WAKEFIELD RI 02879-3804 WAKEFIELD RI 02879-3804 $ 96,784.00 ADVANCED AUTO BODY INC 116 KERSEY ROAD PEACE DALE RI 02879-2427 PEACE DALE RI 02879-2427 $ 52,012.00 ADVANCED COMM TECHNOLOGIES INC WIRELESS ZONE 76 GATE ROAD NORTH KINGSTOWN RI 02852-7145 NORTH KINGSTOWN RI 02852-7145 $ 7,500.00 ALBIES PLACE 99 FORTIN ROAD UNIT 3E KINGSTON RI 02881-1426 KINGSTON RI 02881-1426 $ 62,000.00 ALERT AMBULANCE SERVICE INC 1290 WILSON ROAD FALL RIVER MA 02720-8604 FALL RIVER MA 02720-8604 $ 1,951.00 ALL ONE WORLD 3 PINE TREE LANE WAKEFIELD RI 02879-4466 WAKEFIELD RI 02879-4466 $ 8,475.00 ALL OUTDOORS POWER EQUIP. -

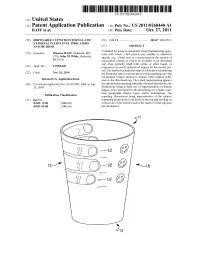

Pub. No.: US 2011/0260440 A1 HAFF Et Al

US 20110260440A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2011/0260440 A1 HAFF et al. (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 27, 2011 (54) DISPOSABLE CUP WITH INTERNAL AND (52) U.S. Cl. ........................................ 283/67; 206/459.1 EXTERNAL FLUID LEVEL INDICATORS AND METHOD (57) ABSTRACT A method for using an associated visual implementing appa (76) Inventors: Maurice HAFF, Bethesda, MD ratus with which a first person may audibly or otherwise (US); John M. White, Bethesda, specify, e.g., a head nod, to a second person the amount of MD (US) unoccupied volume or void to be available in an illustrated cup when partially filled with coffee or other liquid, in (21) Appl. No.: 12/955,409 response to an easily understood inquiry by the second per son. The method includes the steps of a first person exhibiting (22) Filed: Nov. 29, 2010 the illustrated cup to a second person while inquiring as to the unoccupied Volume desired to remain while making refer Related U.S. Application Data ence to the illustrated cup. The visual implementing appara (60) Provisional application No. 61/327,887, filed on Apr. tus cup includes repeating vertically oriented illustrations, the 26, 2010. illustrations being at least one of representations of human fingers, cows, text based words describing cow Sounds, num bers, geographic shapes, logos, and/or indentations. The Publication Classification repeating illustrations being representative of the relative (51) Int. C. remaining proportional Void levels in the cup and residing on B42D IS/00 (2006.01) at least one of the exterior and/or the interior of the cup near B65D 85/00 (2006.01) the rim thereof. -

Codebook: Access Data – Public Use File Faps Access Puf

National Household Food Acquisition and Purchase Survey (FoodAPS) Codebook: Access Data – Public Use File faps_access_puf The OMB clearance number for FoodAPS is 0536-0068. The data were collected by the U.S. Department of Agriculture under authority of U.S.C, Title 7, Section 2026 (a)(1). Information about the entire data collection, including instructions on how to request access to the data, may be found at http://www.ers.usda.gov/foodaps . For further information contact: [email protected] Suggested citation: National Household Food Acquisition and Purchase Survey (FoodAPS): Codebook: Access Data – Public Use File, faps_access_puf. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, November 2016. In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720- 2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. -

The Remaking of Resilient Urban Space: a Case Study of West Hartford Center

Urban Resilience – Evolution, Co-Creation, and the Remaking of Space: A Case Study of West Hartford Center 08 January 2016 Prepared by: Donald J. Poland Submitted for Degree of: PhD in Geography UCL Supervisors: Alan Latham, PhD Senior Lecturer in Geography And Andrew Harris, PhD Lecturer in Geography and Urban Studies University College London – Department of Geography I, Donald J. Poland confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. ____________________________________________________________________________ _ Donald J. Poland 2 Urban Resilience – Evolution, Co-Creation, and the Remaking of Space: University College London – Department of Geography Table of Contents Chapter Title Page Chapter I. Introduction - The Remaking of Resilient Space: A Case Study of West Hartford Center 7 1.00 The Large Urban Bias 7 1.10 The Remaking of Urban Space 11 1.20 Small-City Urbanism and Suburbanization 13 1.30 West Hartford, Connecticut 14 1.40 The Case of West Hartford Center 19 Chapter II. Urban Theory: Exploring and Conceptualizing Urban Space and the Remaking of Space 22 2.00 Introduction 22 2.10 Small City Urbanism 22 2.20 Exploring the Urban 26 2.30 Exploring the Suburban 28 2.40 Exploring Gentrification 35 2.50 Gentrification or Suburbanization 41 2.60 Conclusion 48 Chapter III. Ecological Resilience: A Metaphorical and Theoretical Framework for Understanding the 51 Remaking of Urban Space 3.00 Introduction 51 3.10 Urban Ecology as a Metaphor 52 3.20 Ecological Resilience 59 3.30 Urban Ecological Resilience 61 3.40 Bridging the Urban Ecological Divide 69 3.50 Urban Governance and Ecosystem Management 81 3.60 Conclusion 85 Chapter IV. -

Mob Anti-Maoists Attacks Red Guards

‘ , r ■ y . ' ' ' TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 12, 1967 Bloodmobile Visits St. Mary’s Church Tomorrow; 1:45 to 6:30 p. m. PAGE SIXTEEN iiUtnrli^Bttr Suptiittg iim lii The Anna Addy Sunbeam posal by working foi* activation Illinois jPolice Averace Dally Net Preas Rm The Weather Troop o f the Salvation Army Public Records South Windsor of the North Central Refuse Dis For Uie Week Ended A bout Town will have its first meeting of posal district "as an economical Clear, cool tonight, low in Womptee Deed Arrest 35 After l&epitemiber 11, 1967 the season tomorrow at 3:30^ and lasting solution to the re 40s; sunny and pleasant tomor Atty Mark S. Levin and Maud W. White to Leo X. gional problem of limited areas p.m. in Junior Hall at the Republican Party Issues row, high 76-80. Atly. DaVtd C. Wichman were and Evridiki L. Vedeuios, prop available for dumping,” is Wave of Looting Citadel. admitted yesterday to practice erty at 73-76 Pine St. pledged. 14,805 before the U.S. District Court. Lease Three Campaign Pledges (Continued from Page One) Manchester— A City of Village Charm Senior Girl Scout Troop 2 Extension of the present sew Judge T. Emmet Claire of Rose T. Kronick to Lemd er program in accordMce with financed by federal antipoverty (OlassUted Advertising on Page 20) PRICE SEVEN CENTS will have its first meeting of ployes essential to a growing MANCHESTER, CONN., WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 1967 ficiated at the admission cere O’Fashion, store at 883 Main St. ’The Republican party has the needs of the town areas funds, police said. -

Narrow River Notes Tion (Awesome) Curriculum, and a Revised Narrow River Published Three Times Per Year by Handbook

Mark Your Calendar The 42nd NRPA Annual Meet- ing will be held on Thursday, October 4, 2012, from 7:00 to 10:00 p.m. at the Coastal Insti- tute Auditorium on the URI Narragansett Bay Campus. See page 3 for details. Four Receive NRPA Scholarships Congratulations to the 2012 NRPA/Lesa Meng College Scholarship winners: Caitlin Bousquet, Elizabeth Castro, Annie Hall and Tina Luo. (Background Photo: John McNamara) More on page 3. Maps for Self-Guided Tours of Narrow River 25th Annual Narrow The Rhode Island Blueways Alliance has published a series of River Road Race “paddle maps,” including two maps of Narrow River, that “enable More than 240 runners and watershed organizations throughout Narragansett Bay to showcase walkers participated in this paddling opportunities.” year’s Narrow River Road Race. The Narrow River maps include information on places to put in, See page 4 for race results. points of interest and suggested routes for safely exploring one of the most beautiful waterways in Southern New England. One map Seventh Narrow River shows routes on the Upper and Lower Ponds with access points at Turnaround Swim Gilbert Stuart and Lacey Bridge. The other map covers lower Nar- Fred Bartlett finished the 2012 row River from the Pollock Avenue Boat Ramp to Pettaquamscutt Narrow River Turnaround Swim Cove and the Narrows. The maps also include information on the in 21 minutes and 26 seconds. natural and cultural history of the watershed. Others took almost an hour. “There is no better vantage point than water level to explore the But all enjoyed this annual beauty of the river,” says Jason Considine who headed up the map- open-water swim that celebrates ping project for NRPA, with assistance from fellow NRPA Board the beauty of Narrow River. -

The Use of Zoning to Restrict Fast Food Outlets: a Potential Strategy to Combat Obesity

THE USE OF ZONING TO RESTRICT FAST FOOD OUTLETS: A POTENTIAL STRATEGY TO COMBAT OBESITY October 2005 Julie Samia Mair, JD, MPH, Scholar, The Center for Law and the Public’s Health at Johns Hopkins & Georgetown Universities Matthew W. Pierce, JD, MPH Stephen P. Teret, JD, MPH, Director, The Center for Law and the Public’s Health at Johns Hopkins & Georgetown Universities Acknowledgments: We would like to thank the National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for providing funding to The Center for Law and the Public’s Health at Johns Hopkins & Georgetown Universities for this project. We would also like to express our gratitude to the following individuals for their review of the manuscript and comments: Marice Ashe, JD, MPH, Director, Public Health Law Program, Public Health Institute; Andrew L. Dannenberg, MD, MPH, Project Officer, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Leslie S. Linton, JD, MPH, Deputy Director, Active Living Research, San Diego State University; and Lesley A. Stone, JD, Zuckerman Fellow, Harvard University Kennedy School of Government. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC or the views of individual reviewers. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Part I: Connecting the Dots: Obesity to Fast Food to Zoning 5 I. Obesity as a Current Public Health Crisis 5 II. Why Zoning Fast Food Outlets Can Help Address Obesity 9 A. Food Retail Market and Diet 9 1. Fast Food 10 2. Suggestive Links to Obesity 16 3. Alternatives to Fast Food 17 B. -

DONUTS Youssef Ben Khedda Announce "The Department of State’S Convention Were Held July 2 and 3

J PAGE FOURTEEN iianclr^alfir lEv^nfng H^ralb TUESDAY, JANUARY 23, 1962 -------------^ ^ ---------- ------------ X. hlanchestar Lodge of Masons Cochran, board of religloua educa will meet tonight at 7:30 at the tion. Bigelow St. Lot About Town Masonic Temple. The master ma ITwo Elected Also, Mr. imd Mrs.. George MUTARY WMST son degree t^l be conferred af Announce Engagements Stiles, delegates to Manchester Bought by Holmes Th« Rotary Society of St ter a brief business meeting. Council of Churches; Mr. and Mrs. aM S n B AC K There will be a social hour with Life Deacons Sherwood L. Bowers, delegates to Brldret’e Church wlU sponsor a Purchase of land at the reAr of (BRipOR) public card party at the K of C refreshments. Hartford East Association; and Home tomorrow at 7:30 p.m. Mili John S. Wolcott, 180 Main St., Donald Cook, auditor. the Holmes Funeral Home nas been Sponsored by St. Bridget's tary whlat, setback and bridge Ben Ezra Chapter of B’nal and Louis J. TutUe, 21 Hudson St., Also, Mrs. Marion Stlmson, made with the possibility in mind Roeaiy Society VOL. LXXXI, NO. 96 (TWENTY-EIGHT PAGES— IN TW O SE(7nONS) • / 'MANCHESTER, CONN., WEDNESDAY. JANUARY 24, 1962 (Clamlfted Adverttsiag on Page 26) will be plsiyed. Refreshments will B'rith will meet tonight at 8:30 were elected honorary lifetime Warren Blackwell and Mrs. Helen that It could provide for aodltlonal PRICE nVE CENTS be served and prizes awarded. at Temple Beth Sholoni. A short Rylander, music committee;' Mrs. parking, according to Howaii] deacons of Second Congregational WMlncsdoy.