The Bhutanese Art of Weaving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transmission Component)

Environmental Impact Assessment (Draft) August 2014 (Updated: November 2014) BHU: Second Green Power Development Project (Part B: Transmission Component) Prepared by Druk Green Power Corporation Limited and Tangsibji Hydro Energy Limited for the Asian Development Bank The environmental impact assessment report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. NIKACHHU HYDROPOWER PROJECT, BHUTAN (118 MW) ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR 132 kV TRANSMISSION LINE FROM NIKACHHU POTHEAD YARD TO MANGDECHHU POTHEAD YARD- 2014 Prepared for: Prepared by: Druk Green Power Corporation Limited and Tangsibji Bhutan Consultants & Research (BHUCORE) Hydro Energy Limited (THyE) Taba, Post Box: 955, Thimphu Thori Lam, Thimphu (revised by PWC Consultants) Bhutan Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................. 10 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 24 1.1 Background................................................................................................................. 24 1.2 Purpose of the report .................................................................................................. 24 1.3 Extent and scope of the study ..................................................................................... 24 1.4 Structure -

BHUTAN @Appeal for the Release of Tek Nath Rizal: Prisoner of Conscience

£BHUTAN @Appeal for the Release of Tek Nath Rizal: Prisoner of Conscience Tek Nath Rizal, a prisoner of conscience and a former member of the National Assembly and Royal Advisory Council, is spending his fourth year in prison in Bhutan. He was sentenced to life imprisonment on 16 November 1993, but granted a pardon by King Jigme Singye Wangchuck three days later. However, the pardon was made conditional on the Governments of Nepal and Bhutan resolving the problem of the southern Bhutanese refugees living in refugee camps in Nepal. In January 1994, he was transferred to Chamgang prison from Thimphu Central prison where he had been reportedly held in handcuffs. Amnesty International believes that he is a prisoner of conscience held for the peaceful exercise of his rights to freedom of expression and association and is calling for his immediate and unconditional release. Tek Nath Rizal was sentenced to life imprisonment on 16 November 1993 by the High Court in Thimphu after a trial which lasted 10 months. He was found guilty of four out of nine offences under the Thrimshung Chhenpo (General Law of the Land) and the National Security Act 1992. The charges of which he was found guilty included treasonable acts against the Tsa-Wa-Sum (King, Country and People), attempts to create misunderstanding or hostility between Bhutan and friendly countries, and "sowing communal discord" between different communities in the Kingdom. Tek Nath Rizal had been first arrested in 1988 after petitioning the King about alleged unfair practices adopted during the 1988 census operation, including retroactive application of the 1985 Citizenship Act. -

ICI Venice BHUTAN

Under the patronage of: ENG BHUTAN JOURNEY BEYOND THE SKY BHUTAN VIAGGIO OLTRE IL CIELO BHOUTAN VOYAGE AU CŒUR DU CIEL Exhibition of bhutanese ethnographic pieces MAGAZZINO DEL CAFFÈ – VENEZIA Free admission Support ICI Venice with a donation 1 ◉CURATORS ICI - Institut Culturel International Olivier Perpoint, Chi Phan, Mariarosaria Fogliaro, Martina Masini, Francesca Salvi, Hélène Touzé, Chantal Valdambrini. François Pannier Ethnographic Art Curator Anne Segarra Archives Anne et Ludovic Segarra. ◉ORGANIZATORS ICI - Institut Culturel International Venice - Italy Archive Anne et Ludovic Segarra Paris - France Avec la collaboration de: Le Toît du Monde - Ethnographic Art Gallery in Paris, France, by François Pannier. www.letoitdumonde.com Alain Rouveure Galleries - Tibetan rugs arts and crafts from the Himalayas. www.alainrouveure.com ◉UNDER THE PATRONAGE OF ◉WITH THE SUPPORT OF LAlliance Franaise de Venise Fornasetti Cole & son The Merchant of Venice Fondation Malongo 2 ◉ BHUTAN Journey beyond the sky After the Nepalese Shamanic Art Exhibition showed in Venice and Paris, ICI – International Cultural Institute, presents “BHUTAN Journey beyond the sky”. In December 2012, ICI has organized the first exhibition about Bhutan at “Le 5 Opéra - Compagnies du Monde” in Paris - France. Encouraged by the huge success of the exhibition "Shamanism", with over 16,000 visitors, ICI decided to show more the Himalayan region and produce a new exhibition about Bhutan. From December 2014 to March 2015 will be held "Bhutan: journey beyond the sky" at our venue in Venice, Magazzino del Caffè. ICI offers a journey through time because, of course, the kingdom of Bhutan with the years has changed considerably. To well understand the history and evolution of this Himalayan country a series of conferences will be organized in collaboration with the Department of Studies on Asia and Africa Mediterranean University Ca’ Foscari Venice, under the direction of teachers Stefano Beggiora and Fabian Sanders, in addition to participation of the Association "Amici del Bhutan". -

YTL Life's Haute Summer Fashion Narrative

YTL Issue Twelve The YTL Luxury Magazine The YTL Luxury Magazine The YTL Azur Like It Spring Arrives in Saint-Tropez Cuisine Sans Frontieres Chef Martin Yan on Eating, Drinking & Living PP 15585/10/2010(025760) Sound Trek Celebrated Film Music Composer, Michael Brook The Art of Jamu • SIHH 2011 Report • Tomas Maier OMEGA_YTL. pdf Page 1 3/ 17/ 11, 4: 49 PM Contents 12 14 Life on the Cover 12 The sleek Muse Hôtel de Luxe naturalist is to introduce guests 44 Canadian film music composer reopens this April. to nature’s many wonders. Michael Brook shares his views about his creative 14 Chef Nicolas Le Toumelin of its process, the messages behind M Restaurant lets us in on the Life Feature the music he creates and simple elegance of his cuisine. 28 As the perfect all-weather the advantages of staying holiday destination, Japan's under the Hollywood radar. 16 For over a century, the Côte Niseko offers a wealth of d’Azur, or the French Riviera, has activities for the adventure- been the epicentre of style. inclined. Designer Life 48 Pangkor Laut Estates, the 32 Introducing a designer playlist exclusive beachfront retreat Life Events of tracks created exclusively at the award-winning Pangkor 18 Earth Hour in Singapore. by YTL’s very own music man Laut Resort is the scene for Gavin Aldred. YTL Life's haute summer fashion narrative. Life Bites 34 Chef Martin Yan, the first Asian 22 Hot happenings at to successfully break into the YTL Hotels. US mainstream media, remains Beautiful Life irrepressibly enthusiastic over 58 In an exclusive interview, sharing his love and knowledge Bottega Veneta’s Tomas View of Life of Chinese food. -

5-Day Tour Programme Contact Person: Ms. Karma Choden Email: [email protected]

www.intourbhutan.com Zomlha Building (P.O Box 01645) Thimphu 11001, Bhutan Telefax: 00975-2-328001 Mobile: 00975-1711 8812 5-Day Tour Programme Contact person: Ms. Karma Choden Email: [email protected] Day-by-day Travel Itinerary (Summary) Day Places Places to be visited Associated activities 1. Kuensel Phodrang ( Buddha Visit to 13 traditional arts and crafts, point) the institute of Zorig Chusum. Visit 2. Memorial Choeten (stupa) the centenary farmer’s market Day one Thimphu (weekend vegetable market). Visit Tashichhoe Dzong and witness the 3. Folk Heritage Museum fortress get adorned with special light design as dusk falls. 1. Dochula pass Visit one of the longest suspension bridge nearby Dzong and experience a Day two Punakha “walk to remember” along the bridge. 2. Punakha Dzong Experience river rafting in Phochu river. 1. Visit Chimmi Lhakhang In the evening at the home stay, Day three Punakha experience the traditional cooking 2. Phobjikha valley style and ara (local alcohol) making. In the evening, at the hotel, invite the folk dancers and experience the Day four Wangdue/Paro 1. Visit Bajo town cultural program (traditional cultural dance and mask dance). Day five Paro 1. Hike to Taktsang Day six Paro Drop the guest at the Airport Detail day-by-day itinerary Day 01: Arrive Paro (2250m) & transfer to Thimphu (2350m) Before landing, enjoy the views over the clear blue waters of Paro River and the lush green foliage of the breath taking Himalayas. The distance of about 55kms from paro town and about 50km from airport takes around one hour excluding the stops to Thimphu. -

Monday Morning on the Plane to Paro; Oct 22

Monday Morning on the plane to Paro; Oct 22 Last night we flew into Bangkok, arriving at 5:30 (with a one hour time change from HK, so now we were only 12 hours different than home). We made our way through customs and immigration (remembering the last time we did this we had to wait for Phyllis to prove she did not have Yellow Fever). We stepped outside to catch the shuttle to the airport hotel and were hit with a wall of heat. My glasses fogged up. I had forgotten the heat/humidity of Thailand. We spent the night at the Novotel, a large (really large) airport hotel, where Andy and I had stayed once before. The lobby is beautiful in the Thai style, with trees and sculptures of lotus flowers. We went to our room, and by 8:00 were fast asleep. Good thing as we had to get up at 3:00 (AM!!) to catch our morning flight to Bhutan. We had our breakfast buffet (which opens at 3:30 – lots of travelers here with early morning flights) and shuttled back to the airport to check in with Druk Air, the Royal Bhutan Airline. (Druk in Bhutanese means Thunder Dragon). There were surprising a lot of people there for 4:30 in the morning. We checked in and asked for a window seat as Alvin told us the view flying into Paro was amazing. I asked the agent specifically not to be sitting on the wing. We were driven by bus to the plane. And guess where we ended up sitting? On the wing. -

The Judiciary of the Kingdom of Bhutan

The Judiciary of the Kingdom of Bhutan THE JUDICIARY OF THE KINGDOM OF BHUTAN HISTORICAL BACKGROUND - The Bhutanese legal system has a long traditional background, primarily based on Buddhist natural law and Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal’s Code from early 17th century. The first comprehensive codified laws known as the Thrimzhung Chhenmo or the Supreme Law was enacted by the National Assembly during the Third Druk Gyalpo, His Majesty Jigme Dorji Wangchuck’s reign. MISSION, POLICIES & OBJECTIVES - The Judiciary aims to safeguard, uphold, and administer Justice fairly and independently without fear, favour, or undue delay in accordance with the Rule of Law to inspire trust and confidence and to enhance access to Justice. INDEPENDENCE - Among others, the independence of the Judiciary is manifested through: (a) Separation of judicial power from the apex to the lowest court; (b) Collective independence (the concept of non-interference, jurisdictional monopoly, transfer jurisdiction, control over judicial administration); (c) Institutional and financial independence; (d) Personnel independence (qualification, selection and training, conditions of services, suspension, removal and disciplinary measures. Security of tenure and protection from arbitrary removal from office); (e) Decentralization of all personnel administration and financial operations to respective courts; and (f) Distinctive court building, distinct kabney and court seal. JURISDICTION The Royal Court of Justice The judicial authority of Bhutan is vested in the Royal Courts of Justice comprising the Supreme Court, the High Court, the Dzongkhag Court and the Dungkhag Court. Other courts and tribunals will be established from time to time by the Druk Gyalpo on the recommendation of the National Judicial Commission. Additional Benches are established in some Dzongkhags and Dungkhags with higher caseload. -

Buddhism: It,S Role and Importance in Bhutanese Culture

Mukt Shabd Journal ISSN NO : 2347-3150 Buddhism: it,s role and importance in Bhutanese culture Research Scholar Pankaj Kumar Department of Western History University of Lucknow Abstract Bhutan is situated along the southern slopes of the Great Himalaya range. It is bounded by the table-land of Tibet on the north ; the plains of jalpaiguri district of west Bengal and Goalpara , kamrup and Darrang districts of Assam in the south; the Chumbi valley ( Tibet) , Sikkim and Darjeeling district of west Bengal in the west ; and the kameng district of the Arunachal Pradesh on the east. Before the introduction of Buddhism in Bhutan, the prevalent religion was Bon. Some scholars assert that it was imported from Tibet and India, perhaps in the eighth century when Padmasambhava introduced his lineages of Vajrayana Buddhism into Tibet and the Himalayas. The history of Bhutan is mainly the history of spreading of Buddhism and it,s different sects those creates main bases for Bhutanese culture from ancient time to till now. Many famous monks such like Guru Padmasambhawa presented many religious rituals and symbols before Bhutanese people those became traditions and culture. Buddhism and Bhutanese culture are seems like mirror of each other. Bhutanese dresses, dances, festivals, rituals, paintings etc. directly follows Buddhism. Key word:- Bhutan, Buddhism, Culture, Padmasambhawa, Ngawang Namgyal, Driglamnamzha, Introduction Bhutan is situated along the southern slopes of the Great Himalaya range. It is bounded by the table-land of Tibet on the north ; the plains of jalpaiguri district of west Bengal and Goalpara , kamrup and Darrang districts of Assam in the south; the Chumbi valley ( Tibet) , Sikkim and Darjeeling district of west Bengal in the west ; and the kameng district of the Arunachal Pradesh on the east.1 Bhutan is situated 88 deg.45 min to 92 deg. -

Buddhist Art and Architecture Ebook

BUDDHIST ART AND ARCHITECTURE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert E Fisher | 216 pages | 24 May 1993 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500202654 | English | London, United Kingdom GS Art and Culture | Buddhist Architecture | UPSC Prep | NeoStencil Mahabodhi Temple is an example of one of the oldest brick structures in eastern India. It is considered to be the finest example of Indian brickwork and was highly influential in the development of later architectural traditions. Bodhgaya is a pilgrimage site since Siddhartha achieved enlightenment here and became Gautama Buddha. While the bodhi tree is of immense importance, the Mahabodhi Temple at Bodhgaya is an important reminder of the brickwork of that time. The Mahabodhi Temple is surrounded by stone ralling on all four sides. The design of the temple is unusual. It is, strictly speaking, neither Dravida nor Nagara. It is narrow like a Nagara temple, but it rises without curving, like a Dravida one. The monastic university of Nalanda is a mahavihara as it is a complex of several monasteries of various sizes. Till date, only a small portion of this ancient learning centre has been excavated as most of it lies buried under contemporary civilisation, making further excavations almost impossible. Most of the information about Nalanda is based on the records of Xuan Zang which states that the foundation of a monastery was laid by Kumargupta I in the fifth century CE. Vedika - Vedika is a stone- walled fence that surrounds a Buddhist stupa and symbolically separates the inner sacral from the surrounding secular sphere. Talk to us for. UPSC preparation support! Talk to us for UPSC preparation support! Please wait Free Prep. -

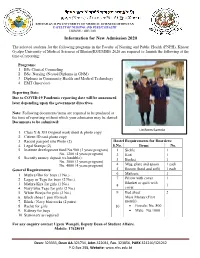

Information for New Admission 2020

KHESAR GYALPO UNIVERSITY OF MEDICAL SCIENCES OF BHUTAN FACULTY OF NURSING AND PUBLIC HEALTH THIMPHU: BHUTAN Information for New Admission 2020 The selected students for the following programs in the Faculty of Nursing and Public Health (FNPH), Khesar Gyalpo University of Medical Sciences of Bhutan(KGUMSB) 2020 are required to furnish the following at the time of reporting: Programs: 1. BSc.Clinical Counseling 2. BSc. Nursing (Nested Diploma in GNM) 3. Diploma in Community Health and Medical Technology 4. EMT (Inservice) Reporting Date: Due to COVID-19 Pandemic reporting date will be announced later depending upon the government directives. Note: Following documents/items are required to be produced at the time of reporting without which your admission may be denied: Documents to be submitted: Uniform Sample 1. Class X & XII Original mark sheet & photo copy 2. Citizen ID card photo copy 3. Recent passport size Photo (2) Hostel Requirements for Boarders: 4. Legal Stamps (2) S.No. Items No. 5. Institute development fund Nu.900 (3 years program) 1 Sickle 1 Nu. 1200 (4 years program) 2 Koti 1 6. Security money deposit (refundable): 3 Bucket 1 Nu. 3000 (3 years program) Nu. 4000 (4 years program) 4 Mug, plate and spoon 1 each 5 Broom (hard and soft) 1 each General Requirements: 1. Mathra Gho for boys (1 No.) 6 Mattress 1 2. Lagay or Tego for boys (2 Nos.) 7 Pillow with cover 1 Blanket or quilt with 3. Mathra Kira for girls (1 No.) 8 1 4. Navy blue Tego for girls (2 No.) cover 5. White Wonju for girls (2 No.) 9 Bed sheet 2 6. -

Festivals and Mountaintop Temples of Bhutan

BHUTAN Festivals and Mountaintop Temples of Bhutan DATES Sep 28–Oct 06, 2017 COST 3,999.00 USD ITINER ARY 9 days, 8 nights BOOK YOUR TRIP Be one of the lucky few to experience this tiny, landlocked nation during its lively festival season. Celebrate the Land of the Thunder Dragon alongside locals through traditional Bhutanese dance, song, and cuisine. Perhaps best-known for its chart-topping measure of Gross National Happiness, this Himalayan nation is home to dramatic landscapes, mystical temples, and fewer than one million people. On this unique trip, you’ll see firsthand how Bhutan is one of the greenest and most sustainable countries on the planet. This adventure is designed for travelers of all ages and most levels of physical ability and is limited to 25 explorers. (See “Note on Hiking and Health” in the Fine Print.) HIGHLIGHTS National Festivals: Experience the sights and sounds of two teschus (festivals)—the first, in Thimphu, is the largest of Bhutan's Buddhist festivals. The second, in Gangtey in the Phobjikha Valley, is less frequented by tourists. At each, you’ll see traditional religious and tantric dance performances and celebrate, pray, and receive blessings for the year ahead. Wildlife and Conservation: The Bhutanese constitution mandates that 60 percent of the country remains forested. During this beautiful time of year, we’ll hike through Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Park, explore the Royal Botanical Park, and spot birds, wild goats, and grey langurs. the Royal Botanical Park, and spot birds, wild goats, and grey langurs. Spiritual Practice: Raise peace flags on the Dochula Pass, meet with Buddhist spiritual leaders, and take in the evening chants at historic temples. -

Chapter 2 Review of Literature

CHAPTER 2 REVIEW OF LITERATURE The second chapter of the present study is on the "Review of Literature". It is divided into three sections namely, theoretical review, technical review and research review. This chapter begins with an overview of how this chapter has been organized, followed by literature reviews. This chapter focuses on what has been done so far and how it is related to the present study being conducted. This chapter has an inventory of the review of literature pertaining to the shawls' history in India and its preservation and conservation practices in museums and private organizations. The research has been formulated with the key endeavour to conserve these precious momentoes for future generations to come and to implement its conservation methods. Fundamental information about fibers and structures that affect the long-term stability of textiles have been provided in the theoretical review. Both internal and external agents of deterioration have been described in the technical review. A wide range of preventive conservation strategies specifically related to shawls has been explored. Basic conservation interventions have been presented, demonstrated and issues in ethical decision making have been addressed in this chapter. These have been covered under the following heads: 2.1 Theoretical Review 2.1.1 Historical background about shawls 2.1.2 Fundamental information about woollen fibers 2.1.3 Agents of deterioration and its preventive conservation 2.1.4 Remedial conservation processes 2.2 Research Review 2.1.1 Historical background about shawls The review of literature is an important step in understanding the researches in India. It helped the researcher in framing and defining the problem, objectives, research design and methodology of the research.