Download the Whole Edition Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commemorating the Overseas-Born Victoria Cross Heroes a First World War Centenary Event

Commemorating the overseas-born Victoria Cross heroes A First World War Centenary event National Memorial Arboretum 5 March 2015 Foreword Foreword The Prime Minister, David Cameron The First World War saw unprecedented sacrifice that changed – and claimed – the lives of millions of people. Even during the darkest of days, Britain was not alone. Our soldiers stood shoulder-to-shoulder with allies from around the Commonwealth and beyond. Today’s event marks the extraordinary sacrifices made by 145 soldiers from around the globe who received the Victoria Cross in recognition of their remarkable valour and devotion to duty fighting with the British forces. These soldiers came from every corner of the globe and all walks of life but were bound together by their courage and determination. The laying of these memorial stones at the National Memorial Arboretum will create a lasting, peaceful and moving monument to these men, who were united in their valiant fight for liberty and civilization. Their sacrifice shall never be forgotten. Foreword Foreword Communities Secretary, Eric Pickles The Centenary of the First World War allows us an opportunity to reflect on and remember a generation which sacrificed so much. Men and boys went off to war for Britain and in every town and village across our country cenotaphs are testimony to the heavy price that so many paid for the freedoms we enjoy today. And Britain did not stand alone, millions came forward to be counted and volunteered from countries around the globe, some of which now make up the Commonwealth. These men fought for a country and a society which spanned continents and places that in many ways could not have been more different. -

The Western Front the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Westernthe Front

Ed 2 June 2015 2 June Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Western Front The Western Creative Media Design ADR003970 Edition 2 June 2015 The Somme Battlefield: Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont Hamel Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The Somme Battlefield: Lochnagar Crater. It was blown at 0728 hours on 1 July 1916. Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front 2nd Edition June 2015 ii | THE WESTERN FRONT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR ISBN: 978-1-874346-45-6 First published in August 2014 by Creative Media Design, Army Headquarters, Andover. Printed by Earle & Ludlow through Williams Lea Ltd, Norwich. Revised and expanded second edition published in June 2015. Text Copyright © Mungo Melvin, Editor, and the Authors listed in the List of Contributors, 2014 & 2015. Sketch Maps Crown Copyright © UK MOD, 2014 & 2015. Images Copyright © Imperial War Museum (IWM), National Army Museum (NAM), Mike St. Maur Sheil/Fields of Battle 14-18, Barbara Taylor and others so captioned. No part of this publication, except for short quotations, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the permission of the Editor and SO1 Commemoration, Army Headquarters, IDL 26, Blenheim Building, Marlborough Lines, Andover, Hampshire, SP11 8HJ. The First World War sketch maps have been produced by the Defence Geographic Centre (DGC), Joint Force Intelligence Group (JFIG), Ministry of Defence, Elmwood Avenue, Feltham, Middlesex, TW13 7AH. United Kingdom. -

Davis, John Henry

Commemoration for the Lives of the Braidwood and District ANZACS “We will remember them well” ROLLROLL OF OF HONOUR HONOUR : MDAVIS,eade, ArthurJohn Henry Stuart ServiceService Number:Number: 21281501 Rank:Rank: SergeantPrivate From 1914 - 1918, 465 volunteers from Braidwood and the District joined the Australian Imperial Force in World War I. 88 lost their lives, never to return home. This is their story. Introduction WORLD WAR I This year, 2015, marks the centenary of the start of the Gallipoli campaign and Australia’s World War I lasted four years, from 4 August 1914 until 11 November 1918. It began after the involvement as a nation in the greatest and most assassination of the heir to the Austrian throne. terrible conflict ever seen to that time. Australians The axis powers were Germany and Austria. ROLL OF HONOUR joined their Armed Forces in large numbers. Their Russia and France were the initial allies. When motives were as varied as their upbringings, from Germany invaded Belgium, Britain entered the a need to save the Empire, of which Australia was war on the side of Russia and France. an integral part, to the desire to have a great adventure. The war was in Europe, the Western Front was in France and Belgium. The Eastern Front was Braidwood and district were no exception. Over Russia and Austria-Hungary. Africa was another front because of colonial possessions on that the four years from 1914 to 1918, from a JOHN HENRY DAVIS population of about 5000, 465 men and women continent, and after Turkey entered the war on 1 – November 1914, the Middle East became from what is now the 2622 postcode area another theatre of war. -

The Report of the Inquiry Into Unresolved Recognition for Past Acts of Naval and Military Gallantry and Valour

Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal THE REPORT OF THE INQUIRY INTO UNRESOLVED RECOGNITION FOR PAST ACTS OF NAVAL AND MILITARY GALLANTRY AND VALOUR THE REPORT OF THE INQUIRY INTO UNRESOLVED RECOGNITION FOR PAST ACTS OF NAVAL AND MILITARY GALLANTRY AND VALOUR This publication has been published by the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal. Copies of this publication are available on the Tribunal’s website: www.defence-honours-tribunal.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2013 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal. Editing and design by Biotext, Canberra. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL INQUIRY INTO UNRESOLVED RECOGNITION FOR PAST ACTS OF NAVAL AND MILITARY GALLANTRY AND VALOUR Senator The Hon. David Feeney Parliamentary Secretary for Defence Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Parliamentary Secretary, I am pleased to present the report of the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal’s Inquiry into Unresolved Recognition for Past Acts of Naval and Military Gallantry and Valour. The Inquiry was conducted in accordance with the Terms of Reference. The Tribunal that conducted the Inquiry arrived unanimously at the findings and recommendations set out in this report. In accordance with the Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal Procedural Rules 2011, this report will be published on the Tribunal’s website — www.defence-honours-tribunal.gov.au — 20 working days after -

A Technical, Administrative and Bureaucratic Analysis of the Victoria Cross and the AIF on the Western Front, 1916-1918

i Behind the Valour: A technical, administrative and bureaucratic analysis of the Victoria Cross and the AIF on the Western Front, 1916-1918 Victoria D’Alton Student Number 3183439 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of New South Wales Australian Defence Force Academy 22 October 2010 ii Originality Statement I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. Victoria D’Alton UNSW Student Number 3183439 22 October 2010 iii For my friend, Lieutenant Paul Kimlin, RAN O156024 1 January 1976 – 2 April 2005 ‘For many are called, but few are chosen.’ Matthew 22:14 iv Abstract This thesis focuses on the how and why the Victoria Cross came to be awarded to 53 soldiers of the AIF on the Western Front from 1916 to 1918. It examines the technical, administrative and bureaucratic history of Australia’s relationship with the Victoria Cross in this significant time and place. -

Inquiry Into Unresolved Recognition for Past Acts of Naval and Military

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1-1 The Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal (the Tribunal) is established under the provisions in Schedule 1 of the Defence Legislation Amendment Act 2010 [No. 1] (Cwlth), which came into effect on 5 January 2011. Before that date, many of the functions of the Tribunal were undertaken by the Defence Honours and Awards Tribunal (the old tribunal), which operated administratively from July 2008. The Defence Legislation Amendment Act contains the provisions for the establishment of the new Defence Honours and Awards Appeals Tribunal (the new Tribunal, or the Tribunal), as well as specifying its membership, powers and functions. The Tribunal’s functions are set out in s. 110UA of the Defence Act 1903 (Cwlth). The Minister may direct the Tribunal to hold an inquiry into a specified matter concerning Defence honours or awards. The Tribunal must then hold an inquiry and report, with recommendations, to the Minister. 1-2 On 21 February 2011 the Parliamentary Secretary for Defence, Senator The Hon. David Feeney, referred the matter of Unresolved Recognition for Past Acts of Naval and Military Gallantry and Valour to the Tribunal. The Terms of Reference for the Inquiry into Unresolved Recognition for Past Acts of Naval and Military Gallantry and Valour (the Inquiry), as agreed on 29 April 2012, are set out in full at the commencement of the Report of the Inquiry into Unresolved Recognition for Past Acts of Naval and Military Gallantry and Valour (the Report). 1-3 The Tribunal comprised the following members: • Emeritus Professor Dennis Pearce, AO (Chairman until 20 June 2011) • Mr Alan Rose, AO (Chairman from 26 September 2011) • Professor David Horner, AM (also Presiding Member from 20 June to 25 September 2011) • Vice Admiral Don Chalmers, AO (Retd) • Brigadier Gary Bornholt, AM, CSC (Retd) • Air Commodore Mark Lax, OAM, CSM (Retd). -

Hamel and the Battle of Amiens: the Australian Contribution to Allied Offensive Operations in 1918 the Australian Corps at Its Zenith1

Masters of War: The AIF in France 1918 MASTERS OF WAR: THE AIF IN FRANCE 1918 THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE HELD AT THE POMPEY ELLIOT MEMORIAL HALL, CAMBERWELL RSL BY MILITARY HISTORY AND HERITAGE, VICTORIA. 14 APRIL 2018 Proudly supported by: Masters of War: The AIF in France 1918 Hamel and the Battle of Amiens: The Australian contribution to Allied Offensive Operations in 1918 The Australian Corps at its Zenith1 Dr Andrew Richardson Introduction “Our attack started at 4.20 this morning and seems to have taken the enemy completely by surprise… […] Who would have believed this possible even 2 months ago? How much easier it is to attack, than to stand and await an enemy’s attack!”2 Field Marshal Douglas Haig’s letter to Lady Haig, 10:30am, 8 August 1918 “August 8th was the black day of the German Army in the history of this war.”3 Quartermaster General Erich Ludendorff, My War Memories, 1914-1918, 1919 At 4:20am on 8 August 1918, three Corps’ worth of British, Australian and Canadian infantry, supported by a Cavalry Division, 2,070 guns4, 432 tanks and 800 aircraft launched an attack that would punch an 11 kilometre salient in the German lines by nightfall. The Battle of Amiens was the British Expeditionary Force’s (BEF) greatest victory of the war, and was the largest single battle the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) had ever fought. The British III Corps assaulted on the Australians’ left flank (on the northern bank of the Somme), the Canadian Corps on their right (south of the Amiens-Chaulnes Railway) and the French First Army further south. -

Our Soldiers Volunteers There Were 57,700 Queensland& Service Men and Women Who Enlisted in the First World War

Mapping our Anzac History Our Soldiers Volunteers There were 57,700 Queensland& service men and women who enlisted in the First World War. At the start of the war, Mareeba’s population was only 1,200 yet over 460 volunteers from our district volunteered for service—most of our young male population. Across the Atherton Tablelands, a total of around 1,000 men and women volunteered to serve Australia. Our volunteers travelled by horse, on foot and by train to enlist in Cairns Townsville. Joining the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) gave them an opportunity to travel abroad and serve their country. There was also the promise of adventure—or so they thought—however reality proved very different. Sadly over one hundred of our soldiers never returned. Some died in action or from wounds, and many from illness. Influenza, tuberculosis, and pneumonia were prevalent among the men who were forced to endure horrific conditions whilst fighting. In Mareeba, we recognise the important contribution and sacrifices that our local volunteers made during the First World War. The Mareeba Shire Council named the following streets in honour of our First World War soldiers who lost their lives: Barrett Street (George Ernest Barrett) Bourke Street (William Bourke) Bowers Street (John Charles Bowers) Brodziak Close (Edward Remilton Brodziak) Colquhoun Street (Harold Robert Colquhoun) Donlen Street (Owen Donlen Jnr) Gibbins Lane (Robert Henry Gibbins) Leswell Street (Jack Leswell) McDowall Street (Thomas Leslie McDowall) Maher Street (Charles Leo Maher) Owens Street (John Joseph Owens) Slade Street (Henry Arthur Slade) Toll Close (Frederick Vivian Toll) Totten Street (Robert Joseph Totten) Wallace Drive (James Angus Wallace) Anzac Avenue in Mareeba was named in 1953 in memory of all soldiers who served in both World Wars. -

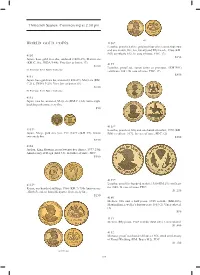

Thirteenth Session, Commencing at 2.30 Pm WORLD GOLD COINS

Thirteenth Session, Commencing at 2.30 pm part WORLD GOLD COINS 4156* Lesotho, proof set, three gold and four silver coins, four, two and one maloti, fi ve, ten, twenty and fi fty licente, 1966 (KM. PS1) certifi cate 852. In case of issue, FDC. (7) 4150 $850 Japan, base gold two shu, undated (1860-69), Manen era (KM.C.18a, JNDA 9-44). Very fi ne or better. (7) 4157 $100 Lesotho, proof set, seven coins as previous, (KM.PS1) Ex Professor Keith Bullen Collection. certifi cate 1401. In case of issue, FDC. (7) $850 4151 Japan, base gold two bu, undated (1868-69), Meiji era (KM. C.21d, JNDA 9-29). Very fi ne or better. (8) $150 Ex Professor Keith Bullen Collection. 4152 Japan, two bu, undated, Meiji era (KM.C.21d). Some slight buckling otherwise very fi ne. $50 4158* 4153* Lesotho, proof set, fi fty and one hundred maloti, 1976 (KM. Japan, Meiji, gold one yen, Yr4 (1871) (KM.Y9). Good PS8) certifi cate 1072. In case of issue, FDC. (2) extremely fi ne. $500 $750 4154 Jordan, King Hussein, proof twenty fi ve dinars, 1977 25th Anniversary of Reign (KM.33). In folder of issue, FDC. $500 4159* 4155* Lesotho, proof fi ve hundred maloti, 1980 (KM.29) certifi cate Kenya, one hundred shillings, 1966 (KM.7) 75th Anniversary no 1040. In case of issue, FDC. - Birth President Jomo Kenyatta. Extremely fi ne. $1,250 $250 4160 Mexico, two and a half pesos, 1945 restrike (KM.463); Maximillian, jeweller's fantasy peso 1865 (2). -

Battle of Hamel Victoria Cross

Battle of Hamel Victoria Cross Harry Dalziel V.C. Celebrating 100 years 4 July 1918 - 4 July 2018 Private Henry Dalziel V.C. 15th Australian Infantry Battalion, A.I.F. 4th July 1918, at Hamel Wood, France CITATION: For most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty when in action with a lewis gun section. His company met with determined resistance from a strong point which was strongly garrisoned, manned by numerous machine-guns and, XQGDPDJHGE\RXUDUWLOOHU\ͤUHZDVDOVRSURWHFWHGE\VWURQJ wire entanglements. A heavy concentration of machine-gun ͤUHFDXVHGPDQ\FDVXDOWLHVDQGKHOGXSRXUDGYDQFH His Lewis gun having come into action and silenced enemy JXQVLQRQHGLUHFWLRQDQHQHP\JXQRSHQHGͤUHIURPDQRWKHU direction. Private Dalziel dashed at it and with his revolver, killed or captured the entire crew and gun, and allowed our advance to continue. He was severely wounded in the hand, EXWFDUULHGRQDQGWRRNSDUWLQWKHFDSWXUHRIWKHͤQDOREMHFWLYH He twice went over open ground under heavy enemy artillery DQG PDFKLQHJXQ ͤUH WR VHFXUH DPPXQLWLRQ DQG WKRXJK VXIIHULQJIURPFRQVLGHUDEOHORVVRIEORRGKHͤOOHGPDJD]LQHV and served his gun until severely wounded through the head. +LVPDJQLͤFHQWEUDYHU\DQGGHYRWLRQWRGXW\ZDVDQLQVSLULQJ H[DPSOH WR DOO KLV FRPUDGHV DQG KLV GDVK DQG XQVHOͤVK courage at a critical time undoubtedly saved many lives and turned what would have been a serious check into a splendid success. (London Gazette: 17th August 1918.) Dalziel’s actions occurred during the Battle of Hamel, when the 15th Battalion was given the task of capturing a position known as Pear Trench. Page 2 RIGHT: Atherton Cricket c 1915. Harry in the centre, back row, wearing white with black belt. BELOW: Harry Dalziel V.C. c.1918/19, ͤYH PRQWKV DIWHU KLV DFWLRQ DW +DPHO 7KLV LV OLNHO\ DQ RͦFLDO photograph taken in London. -

![Victoria Cross Recipients by Electorate Electorates Online Only 22 April 2010 Printable Version [PDF 185KB]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4393/victoria-cross-recipients-by-electorate-electorates-online-only-22-april-2010-printable-version-pdf-185kb-8774393.webp)

Victoria Cross Recipients by Electorate Electorates Online Only 22 April 2010 Printable Version [PDF 185KB]

VC recipients by electorate Background Note Index Introduction Background Note Abreviations List of Victoria Cross recipients by electorate Electorates Online only 22 April 2010 printable version [PDF 185KB] New South Wales Marty Harris Victoria with assistance from Nicholas Fuller, Laura Rayner and Brooke McDonagh Foreign Affairs, Defence and Security Section Queensland Western Australia Introduction South Australia Purpose of publication Tasmania The intent of this website is to allow Members and Senators to identify Victoria Cross (VC) winners with ties to Northern Territory particular electorates. A Victoria Cross winner is defined as ‘connected’ with a specific federal House of Representatives electorate if the recipient:: Australian Capital Territory ● was born in the electorate ● resided in the electorate when he enlisted ● died in the electorate or ● is buried or was cremated in the electorate. The Victoria Cross … is the pre-eminent award for acts of bravery in wartime and Australia’s highest military honour. It is awarded to persons who, in the presence of the enemy, display the most conspicuous gallantry; a daring or pre-eminent act of valour or self-sacrifice; or extreme devotion to duty.1 History http://www.aph.gov.au/Library/pubs/BN/fads/VC/VCbyElectorate.htm (1 of 17) [27/04/2010 2:02:59 PM] VC recipients by electorate The (Imperial) Victoria Cross was created in 1856, and retrospectively covered the Crimean War beginning in 1854.2 It was first awarded to 62 sailors and soldiers following the Indian Mutiny in 1957. The Victoria Cross for Australia was inaugurated in 1991, and is the highest Australian award in the Australian system of Honours and Awards. -

Your Defence Community Magazine JULY/AUGUST 2018

Your Defence Community Magazine JULY/AUGUST 2018 L S U R S B B S R N A R N I C A H C C A Y R L I I N M G A F F O E R C O E N U R D E F 1 SIT-REP July/August 2018The price of liberty is eternal vigilance museum and interpretive centre The Museum is located inside the RSL Club, upstairs in the Kokoda Hall. Our opening hours are Monday - Friday, 9:00am - 4:30pm. free entry 2 SIT-REP July/August 2018 L S U B R S B S R N A R N I C A H C C Y A L R I Contents I M N A G F F E O C 4 President's Report R N O E U R D E F 5 Secretary's Report The Returned & Services League of Australia Cairns Sub-Branch 6 115 The Esplanade Cairns Meet the New Board of Directors PO Box 55 Cairns Qld 4870 07 4051 5254 10 News Briefs [email protected] 14 PAWS News EXECUTIVE BOARD President: Buster Todd (Air Force) [email protected] 16 Kokoda Hall Museum Report Vice President: Peter Hayton (Air Force) [email protected] 20 Treasurer: Ben Hemphill (Navy) Ex-Service Organisation Reports [email protected] BOARD 22 Roy Hartman – Life Member Director of Infrastructure: John Paterson (Army) [email protected] 26 Profiles – Volunteers, Successful Director of Marketing: Veterans, Sub-Branch Members Katherine Young (Navy) [email protected] Director of Membership: 28 Events – Anzac Day Rob Lee (Army) [email protected] Director of Rehabilitation and Compensation and Wellbeing: 34 Member Submissions Kristen Rice (Navy) [email protected] Director of Younger Veterans Advisory: 42 Calendar of Events Mark Rix (Navy) [email protected] STAFF Secretary: Mal McCullough (Army) [email protected] Marketing & Events Coordinator: Rebecca Milliner [email protected] Administration Officer: COVER: Cameron Vonarx (Army) Roy Hartman OAM – [email protected] Cairns RSL Sub-Branch PENSIONS ADVOCACY AND WELFARE SERVICES (PAWS) Life Member.