Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seasons Greetings to List)

Everything you need to hit the trail! Seasons • 4WDriving Equipment • Cooking • Kayaks SUMMER 2008 • Backpacks • Fishing • Refrigeration & Coolers Greetings ISSUE#49 • Books, Maps & DVD’s • Gas Refills • Sleeping Bags RRP $6.00 • Camping Tables & Cupboards • Gazebos • Swags • Caravanning Equipment • Generators • Tents • Clothing for Summer & Winter • GPS Systems • Watersports s l e t t e u l m u n T • Bags • Headlamps • Portable Showers & Toilets N e w r f o r r i e n d s B i b b r a c k • Bait • Hiking Boots • Pumps t h e f o f t h e • Batteries • Hobie Kayaks & • Stretchers • Boating Accessories • Sunglasses • Compasses • Kayak Carts • Tackle & Tackle Boxes • Containers • Knives • Towels • Diving & Snorkelling Equipment • Lanterns • Fishing – Fly/Mosquitos The 10th Anniversary Finale • Fins • Lights • Reels • Masks • Masks • Rods • Footwear • Mats & Blow Up Beds • Tools • Hats • Nets • Torches Bibbulmun Track Foundation members receive 10% OFF* all recommended retail prices on Ranger Outdoors’ huge range of quality gear. 14 stores locally owned and operated located around Western Australia • www.rangeroutdoors.com.au Proudly Proud Sponsor BALCATTA Cnr Wanneroo Rd & Amelia Street 9344 7343 MANDURAH 65 Reserve Drive 9583 4800 Western Australian of the Bibbulmun Owned and Operated Track Foundation BENTLEY 1163 Albany Hwy (Cnr Bedford Street) 9356 5177 MIDLAND Midland Central (Cnr Clayton & Lloyd St) 9274 4044 OPEN ALL WEEKEND BUSSELTON Home Depot Strelly Street 9754 8500 MORLEY 129 Russell Street (Opp. Galleria Bus Station) 9375 5000 SUMMER -

Commemorating the Overseas-Born Victoria Cross Heroes a First World War Centenary Event

Commemorating the overseas-born Victoria Cross heroes A First World War Centenary event National Memorial Arboretum 5 March 2015 Foreword Foreword The Prime Minister, David Cameron The First World War saw unprecedented sacrifice that changed – and claimed – the lives of millions of people. Even during the darkest of days, Britain was not alone. Our soldiers stood shoulder-to-shoulder with allies from around the Commonwealth and beyond. Today’s event marks the extraordinary sacrifices made by 145 soldiers from around the globe who received the Victoria Cross in recognition of their remarkable valour and devotion to duty fighting with the British forces. These soldiers came from every corner of the globe and all walks of life but were bound together by their courage and determination. The laying of these memorial stones at the National Memorial Arboretum will create a lasting, peaceful and moving monument to these men, who were united in their valiant fight for liberty and civilization. Their sacrifice shall never be forgotten. Foreword Foreword Communities Secretary, Eric Pickles The Centenary of the First World War allows us an opportunity to reflect on and remember a generation which sacrificed so much. Men and boys went off to war for Britain and in every town and village across our country cenotaphs are testimony to the heavy price that so many paid for the freedoms we enjoy today. And Britain did not stand alone, millions came forward to be counted and volunteered from countries around the globe, some of which now make up the Commonwealth. These men fought for a country and a society which spanned continents and places that in many ways could not have been more different. -

The Western Front the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Westernthe Front

Ed 2 June 2015 2 June Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Western Front The Western Creative Media Design ADR003970 Edition 2 June 2015 The Somme Battlefield: Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont Hamel Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The Somme Battlefield: Lochnagar Crater. It was blown at 0728 hours on 1 July 1916. Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front 2nd Edition June 2015 ii | THE WESTERN FRONT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR ISBN: 978-1-874346-45-6 First published in August 2014 by Creative Media Design, Army Headquarters, Andover. Printed by Earle & Ludlow through Williams Lea Ltd, Norwich. Revised and expanded second edition published in June 2015. Text Copyright © Mungo Melvin, Editor, and the Authors listed in the List of Contributors, 2014 & 2015. Sketch Maps Crown Copyright © UK MOD, 2014 & 2015. Images Copyright © Imperial War Museum (IWM), National Army Museum (NAM), Mike St. Maur Sheil/Fields of Battle 14-18, Barbara Taylor and others so captioned. No part of this publication, except for short quotations, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the permission of the Editor and SO1 Commemoration, Army Headquarters, IDL 26, Blenheim Building, Marlborough Lines, Andover, Hampshire, SP11 8HJ. The First World War sketch maps have been produced by the Defence Geographic Centre (DGC), Joint Force Intelligence Group (JFIG), Ministry of Defence, Elmwood Avenue, Feltham, Middlesex, TW13 7AH. United Kingdom. -

Mr Shane Love; Mr Ian Blayney; Mr Donald Punch; Mr Terry Redman; Mr Bill Johnston

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 20 May 2020] p2970b-2995a Mr Vincent Catania; Mr Dave Kelly; Mr Shane Love; Mr Ian Blayney; Mr Donald Punch; Mr Terry Redman; Mr Bill Johnston CORONAVIRUS — SMALL BUSINESS — RELIEF AND RECOVERY MEASURES Motion MR V.A. CATANIA (North West Central) [4.02 pm]: I move — That this house calls upon the Labor government to immediately address the shortfall in support for Western Australian small businesses and industries suffering because they are unable to access relief and recovery measures. We have moved this motion today, and I am going to outline the reasons that small businesses, particularly tourism businesses in regional Western Australia, are suffering at the moment due to, obviously, the COVID-19 pandemic and how it has affected everyone from all walks of life. Every which way that we operate in society has been affected. I want to talk about small business. More than 224 000 small businesses operate in Western Australia, employing around 490 000 workers and contributing billions of dollars to the Western Australian economy. There are more than 50 000 small businesses in regional Western Australia. Nearly half the jobs created in Western Australia are created by the small business sector, and small business accounts for half of WA’s private sector industry employment. Small businesses in regional towns and communities support local economies and communities, and that is why we want people to buy local and support our businesses. Before COVID-19, small businesses were faced with a range of challenges. The higher cost of doing business is generally different from region to region, and I will explain the difference between the southern and northern parts of Western Australia. -

Parliamentary Handbook the Western Australian Parliamentary Handbook Twenty-Fourth Edition Twenty-Fourth Edition

The Western Australian Parliamentary Handbook Parliamentary Australian Western The The Western Australian Parliamentary Handbook Twenty-Fourth Edition Twenty-Fourth Twenty-Fourth Edition David Black The Western Australian PARLIAMENTARY HANDBOOK TWENTY-FOURTH EDITION DAVID BLACK (editor) www.parliament.wa.gov.au Parliament of Western Australia First edition 1922 Second edition 1927 Third edition 1937 Fourth edition 1944 Fifth edition 1947 Sixth edition 1950 Seventh edition 1953 Eighth edition 1956 Ninth edition 1959 Tenth edition 1963 Eleventh edition 1965 Twelfth edition 1968 Thirteenth edition 1971 Fourteenth edition 1974 Fifteenth edition 1977 Sixteenth edition 1980 Seventeenth edition 1984 Centenary edition (Revised) 1990 Supplement to the Centenary Edition 1994 Nineteenth edition (Revised) 1998 Twentieth edition (Revised) 2002 Twenty-first edition (Revised) 2005 Twenty-second edition (Revised) 2009 Twenty-third edition (Revised) 2013 Twenty-fourth edition (Revised) 2018 ISBN - 978-1-925724-15-8 The Western Australian Parliamentary Handbook The 24th Edition iv The Western Australian Parliamentary Handbook The 24th Edition PREFACE As an integral part of the Western Australian parliamentary history collection, the 24th edition of the Parliamentary Handbook is impressive in its level of detail and easy reference for anyone interested in the Parliament of Western Australia and the development of parliamentary democracy in this State since 1832. The first edition of the Parliamentary Handbook was published in 1922 and together the succeeding volumes represent one of the best historical record of any Parliament in Australia. In this edition a significant restructure of the Handbook has taken place in an effort to improve usability for the reader. The staff of both Houses of Parliament have done an enormous amount of work to restructure this volume for easier reference which has resulted in a more accurate, reliable and internally consistent body of work. -

Letters from Long ‘Un

Letters from Long ‘un Captain Robert James Henderson, MC and Bar 13th Battalion AIF 1915-1918 Bob Henderson in France, winter 1917 Compiled by David Garred Jones 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This compilation arose out of a wider study into the movements, actions and stories of the “Originals” of the 13th Australian Infantry Battalion in World War 1. Part of that work involved reviewing the hundreds of diaries and thousands of letters that had been donated to the various State libraries and the Australian War Memorial. Much of this first-hand material is now available on-line, and in some cases has been transcribed by the skilled and dedicated staff of those institutions. Amongst that wealth of material are the letters of Captain Robert James Henderson, MC and Bar, of the 13th Battalion. They encapsulate the thoughts and feelings of a man who started in 1915 as a private, saw action in Gallipoli, Fleurbaix, Pozieres, Mouquet Farm, Messines, Passchendaele and Villers-Bretonneux, rising through the ranks to Captain. Henderson’s family donated his letters, postcards, certificates, awards and other ephemera to the Australian War Memorial (“AWM”). They have been digitised and posted on line under the accession code AWM2016.30.1 through to AWM2016.30.9. I am deeply grateful to the AWM for making this valuable historical archive so readily accessible. As well as Henderson’s own photographs, I have included some relevant images from the AWM and other sources, all of which are acknowledged in the captions to the photos. I have also added, in italics, the locations from where each letter was written (if not already included in the original letter). -

Greyhounds - Namely That Similar to the Recent Changes in ACT, Victoria and NSW

From: Subject: I support an end to compulsory greyhound muzzling Date: Saturday, 3 August 2019 7:24:06 AM Dear Reece Whitby MP, cc: Cat and Dog statutory review I would like to express my support for the complete removal of the section 33(1) of the Dog Act 1976 in relation to companion pet greyhounds - namely that similar to the recent changes in ACT, Victoria and NSW. I believe companion greyhounds should be allowed to go muzzle free in public without the requirement to complete a training programme. I support the removal of this law for companion pet greyhounds for the following reasons: 1. Greyhounds are kept as pets in countries all over the world muzzle free and there has been no increased incidence of greyhound dog bites to people, other dogs or animals 2. The RSPCA have found no evidence to suggest that greyhounds as a breed pose any greater risk than other dog breeds 3. Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania are the only Australian states still with this law. All other states (VIC, NSW, QLD, ACT, NT) have removed this law 4. The view supported by veterinary behaviourists is that the behaviour of a particular dog should be based on that individual dogs attributes not its breed 5. As a breed, greyhounds are known for their generally friendly and gentle disposition, even despite their upbringing in the racing industry 6. Muzzling contributes to unwarranted negative public perceptions about greyhounds and their suitability as pets, impacting adoption opportunities 7. There is no evidence that shows that Breed Specific Legislation such as greyhounds wearing muzzles is effective in preventing or reducing dog attacks 8. -

RSL Hellenic Sub-Branch Memorial Hall, 14A Ferrars Pl, South , Melbourne Vic 3205 RETURNED SOLDIER – “APOSTRATOS” English Newsletter Supplement - June 2014

RSL Hellenic Sub-Branch Memorial Hall, 14A Ferrars Pl, South , Melbourne Vic 3205 RETURNED SOLDIER – “APOSTRATOS” English Newsletter Supplement - June 2014 Dear Members and Friends of the RSL Hellenic Sub-Branch Our Sub-Branch continues to grow. A special welcome to our newest members:- Andreas Singeniotis, Rev. Jeremy Ross Morgan, Sam Kelpezidis, Vasilios Georgakis, John Michanetzis, Anthelia Tzanis, Alexandros Lambrou, Constantine Dimaras, Peter Diakrousis, Apostolos Sinis, Maria Sinis, Jim Colias and Jim Anagnostou. A special thanks to all our ANZAC DAY badge sellers, whom again did a wonderful job raising $7,800 for the RSL. I hope you enjoy this edition of the Returned Soldier “Apostratos” Newsletter Steve Kyritsis, President Anzac Day 25th April 2014 Around seventy Hellenic Sub Branch members and family turned up to march in the Anzac Day parade. The procession was led by Army Cadets from 30 ACU Sunshine and 305 ACU Surrey Hills Army Cadet units who proudly held the Greek, Australian and Cypriot flags, followed by students from St Johns Greek school. Continued on page 4 1 Please email any newsletter content suggestions including photos you may have to Emanuel Karvelas at "[email protected]" RSL Hellenic Sub-Branch Memorial Hall, 14A Ferrars Pl, South , Melbourne Vic 3205 RETURNED SOLDIER – “APOSTRATOS” English Newsletter Supplement - June 2014 Date Milestones and Past Events 27th April 2014 The Sub-Branch Annual General Meeting was held at the Sub-Branch. 25th April 2014 ANZAC Day. 4th May 2014 Mother’s Day at the Hellenic Sub-Branch. th 4 May 2014 72nd Anniversary Commemoration, WWII Battle of the Coral Sea Monday Members of the Hellenic Sub-Branch met The Chief of Staff of the 26th May 2014 Hellenic National Defense General Staff (HNDGS), Lieutenant General Georgios Petkos and other Senior Hellenic and Australian Military Officers at Victoria Barracks. -

Department of Lands.Pdf

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 16 September 2015] p6507b-6516a Mr Joe Francis; Ms Margaret Quirk EMERGENCY SERVICES LEVY Motion Resumed from 9 September on the following motion moved by Ms M.M. Quirk — That this house condemns the Barnett government for misappropriating funds collected by the emergency services levy for purely administrative purposes instead of for frontline emergency needs, and calls for a system of independent allocation of ESL funds to be implemented as recommended in the first Keelty inquiry. MR J.M. FRANCIS (Jandakot — Minister for Emergency Services) [5.40 pm]: I start by acknowledging members of the opposition who have spoken to this motion; I do not have a list of names with me, but I know the member for Armadale made a contribution last Wednesday before this motion was adjourned. I say from the start that obviously the government does not support the motion brought to the house by the shadow Minister for Emergency Services, the member for Girrawheen, and I will outline the reasons why. Firstly let me say that the wording of the motion — The ACTING SPEAKER (Mr I.M. Britza): Members, if you want to have a conversation, I ask you to leave the chamber, please. Mr J.M. FRANCIS: Firstly let me say that obviously the government will not support this motion and I will outline the reasons why. I do not mean to be provocative by saying this, but I would suggest that the motion is fairly harshly worded and, I would go so far as to say, pretty offensive to both the Fire and Emergency Services Commissioner and the staff of the Department of Fire and Emergency Services, purely through the use of the words “misappropriating funds”. -

9 Rar Associaion (Nsw)

December 2012 ISSUE 3 ( 2012) ANZAC MEMORIAL—REMEMBRANCE DAY HIGHLIGHTS: Reunion 2012 News and Photos The Pipes & Drums of Knox College with the RAR VC: Corporal D. Keighran banners of the 9th Battalion and our comrades in Book Review: Who Dares Wins arms, the Tunnel Rats. Inside this issue: Editor’s Notes 2 Reunion 2012 News 3 Vale 4 Reunion 2012 News 5-9 Membership News 10-11 Cpl D. Keighran VC 12-13 Book Review 14 Mates Corner 15-17 Blue Mountains Report 18 Aircraft News 19 Photo credit: Tony Mulavey Season’s Greetings 20 9 RAR ASSOCIAION (NSW) MEMBERSHIP &CORRESPONDENCE: C/- Eric Pope 19 Ingram Ave Milperra NSW 2214 Phone: 0(2) 9774-5113 or email: [email protected] TREASURER : C/. Stephen Nugent 33 Bertana Crescent Mona Vale 2103 Phone:(02) 9997-1552 or email: [email protected] ROLL CALL: C/. Barney 73 Barclay Rd North Rocks 2151 Phone: ( 02) 9873-5209 Mobile: 0488-727-475 or email: [email protected] PAGE 2 ROLL CALL DECEMBER 2012 EDITOR’S REPORT Well the highlight of 3 years planning by the NSW Committee with the bulk of the organising falling on the shoulders of Trevor and Doug (and Sharon and Leslie) came to a GRAND CLIMAX (no sexual connotation intended) in November. Trevor introduced a new member to the NSW committee Greg Barr-Jones a couple of years ago. Trev knew Gregg through the 2/1st Infantry Battalion Association as both their fathers were members of that unit. That contact was to reap huge benefits for the Reunion coffers. -

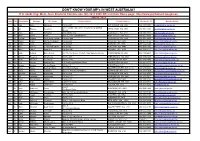

DON't KNOW YOUR MP's in WEST AUSTRALIA? If in Doubt Ring: West

DON'T KNOW YOUR MP's IN WEST AUSTRALIA? If in doubt ring: West. Aust. Electoral Commission (08) 9214 0400 OR visit their Home page: http://www.parliament.wa.gov.au HOUSE : MLA Hon. Title First Name Surname Electorate Postal address Postal Address Electorate Tel Member Email Ms Lisa Baker Maylands PO Box 907 INGLEWOOD WA 6932 (08) 9370 3550 [email protected] Unit 1 Druid's Hall, Corner of Durlacher & Sanford Mr Ian Blayney Geraldton GERALDTON WA 6530 (08) 9964 1640 [email protected] Streets Dr Tony Buti Armadale 2898 Albany Hwy KELMSCOTT WA 6111 (08) 9495 4877 [email protected] Mr John Carey Perth Suite 2, 448 Fitzgerald Street NORTH PERTH WA 6006 (08) 9227 8040 [email protected] Mr Vincent Catania North West Central PO Box 1000 CARNARVON WA 6701 (08) 9941 2999 [email protected] Mrs Robyn Clarke Murray-Wellington PO Box 668 PINJARRA WA 6208 (08) 9531 3155 [email protected] Hon Mr Roger Cook Kwinana PO Box 428 KWINANA WA 6966 (08) 6552 6500 [email protected] Hon Ms Mia Davies Central Wheatbelt PO Box 92 NORTHAM WA 6401 (08) 9041 1702 [email protected] Ms Josie Farrer Kimberley PO Box 1807 BROOME WA 6725 (08) 9192 3111 [email protected] Mr Mark Folkard Burns Beach Unit C6, Currambine Central, 1244 Marmion Avenue CURRAMBINE WA 6028 (08) 9305 4099 [email protected] Ms Janine Freeman Mirrabooka PO Box 669 MIRRABOOKA WA 6941 (08) 9345 2005 [email protected] Ms Emily Hamilton Joondalup PO Box 3478 JOONDALUP WA 6027 (08) 9300 3990 [email protected] Hon Mrs Liza Harvey Scarborough -

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Tuesday, 12 September 2017

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Tuesday, 12 September 2017] p3773a-3819a Mr Ben Wyatt; Ms Mia Davies; Ms Jessica Shaw; Mr Sean L'Estrange; Mr Bill Marmion; Mr Terry Redman; Mr Matthew Hughes; Ms Libby Mettam; Mr Mark Folkard; Mr John Carey; Mr Reece Whitby; Mr Stephen Price; Ms Lisa Baker; Ms Janine Freeman; Mr Simon Millman; Mr Chris Tallentire; Ms Sabine Winton; Ms Margaret Quirk APPROPRIATION (RECURRENT 2017–18) BILL 2017 APPROPRIATION (CAPITAL 2017–18) BILL 2017 Declaration as Urgent On motion by Mr B.S. Wyatt (Treasurer), resolved — That in accordance with standing order 168(2), the Appropriation (Recurrent 2017–18) Bill 2017 and the Appropriation (Capital 2017–18) Bill 2017 be considered urgent bills. Cognate Debate Leave granted for the Appropriation (Recurrent 2017–18) Bill 2017 and the Appropriation (Capital 2017–18) Bill 2017 to be considered cognately, and for the Appropriation (Recurrent 2017–18) Bill 2017 to be the principal bill. Second Reading — Cognate Debate Resumed from 14 September. MS M.J. DAVIES (Central Wheatbelt — Leader of the National Party) [4.10 pm]: I rise to contribute to the second reading debate on the Appropriation (Recurrent 2017–18) Bill 2017 and the Appropriation (Capital 2017–18) Bill 2017. What an absolute con job we have heard in this house this afternoon about the budget that the Labor Party has brought down. They have all drunk the Kool-Aid. They have read the talking points that have been circulated to all and sundry and they actually believe them. They believe that this is a good budget. Several members interjected.