PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations Among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-29-2017 An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC001765 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Mehta, Venu Vrundavan, "An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA" (2017). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3204. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3204 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF SECTARIAN NEGOTIATIONS AMONG DIASPORA JAINS IN THE USA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Venu Vrundavan Mehta 2017 To: Dean John F. Stack Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs This thesis, written by Venu Vrundavan Mehta, and entitled An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. ______________________________________________ Albert Kafui Wuaku ______________________________________________ Iqbal Akhtar ______________________________________________ Steven M. Vose, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 29, 2017 This thesis of Venu Vrundavan Mehta is approved. -

Concise Ancient History of Indonesia.Pdf

CONCISE ANCIENT HISTORY OF INDONESIA CONCISE ANCIENT HISTORY O F INDONESIA BY SATYAWATI SULEIMAN THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION JAKARTA Copyright by The Archaeological Foundation ]or The National Archaeological Institute 1974 Sponsored by The Ford Foundation Printed by Djambatan — Jakarta Percetakan Endang CONTENTS Preface • • VI I. The Prehistory of Indonesia 1 Early man ; The Foodgathering Stage or Palaeolithic ; The Developed Stage of Foodgathering or Epi-Palaeo- lithic ; The Foodproducing Stage or Neolithic ; The Stage of Craftsmanship or The Early Metal Stage. II. The first contacts with Hinduism and Buddhism 10 III. The first inscriptions 14 IV. Sumatra — The rise of Srivijaya 16 V. Sanjayas and Shailendras 19 VI. Shailendras in Sumatra • •.. 23 VII. Java from 860 A.D. to the 12th century • • 27 VIII. Singhasari • • 30 IX. Majapahit 33 X. The Nusantara : The other islands 38 West Java ; Bali ; Sumatra ; Kalimantan. Bibliography 52 V PREFACE This book is intended to serve as a framework for the ancient history of Indonesia in a concise form. Published for the first time more than a decade ago as a booklet in a modest cyclostyled shape by the Cultural Department of the Indonesian Embassy in India, it has been revised several times in Jakarta in the same form to keep up to date with new discoveries and current theories. Since it seemed to have filled a need felt by foreigners as well as Indonesians to obtain an elementary knowledge of Indonesia's past, it has been thought wise to publish it now in a printed form with the aim to reach a larger public than before. -

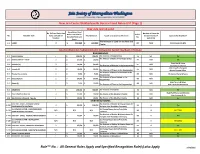

Fixed Nakro LIST (Page 1)

Jain Society of Metropolitan Washington A non-profit tax-exempt religious organization, id # 54-1139623 New Jain Center/Shikharbandhi Derasar Fixed Nakro LIST (Page 1) NEW JAIN CENTER LAND Amount per Fixed No. Of Fixed Nakro Line Number of Passes for Nakro Line Item for Rule** No Donation Item Items available for Total Donation Laabh to be given to the Donors the Ceremonies (if Sponsorship Available? Donation from each No. Donation applicable) Donor The Nirmaan of Land for the New Jain L-1 LAND 2$ 250,000 $ 500,000 R7 N/A Shah Kamlesh & Gita Center SHANKHESHWAR PARSHWANATH BHAGWAN (SHWETAMBAR) DERASAR RANGMANDAP S-1 RANGMANDAP 3 $ 100,001 $ 300,003 The Nirmaan of Rangmandap R5 N/A Yes The Nirmaan of Dome in the Rangmandap S-2 RANGMANDAP - DOME 2$ 25,001 $ 50,002 R5 N/A Yes Shah Atul & Aruna S-3 Bhandar (2) 2$ 10,001 $ 20,002 R5 N/A The Nirmaan of Bhandar in the Rangmandap Shah Dipak and Jyoti Shah Arvind & Sanyukta S-4 Trigado (2) 2$ 10,001 $ 20,002 R5 N/A The Nirmaan of Trigado in the Rangmandap Ajmera Devang & Rani The Nirmaan of Musical Instruments in the S-5 Musical Instruments 1$ 5,001 $ 5,001 R5 N/A Dharamsi Manoj & Kanta Rangmandap The Nirmaan of Sound System in the S-6 Sound System 1$ 20,001 $ 20,001 R5 N/A Yes Rangmandap Shah Paresh & Shilpa S-7 Ghant (2) 2$ 5,001 $ 10,002 R5 N/A The Nirmaan of Ghant in the Rangmandap Shah Harshid & Hemangini S-8 GHABHARA 3 $ 100,001 $ 300,003 The Nirmaan of Ghabhara R5 N/A Yes Dalal Fakirchand and Manjula S-9 Main Ghabhara Door (s) 2$ 15,001 $ 30,002 The Nirman of the Ghabhara Door(s) R5 N/A -

Appendix D Chinese Personal Names and Their Japanese Equivalents

-1155 Appendix D Chinese Personal Names and Their Japanese Equivalents Note: Chinese names are romanized according to the traditional Wade-Giles system. The pinyin romanization appears in parentheses. Chinese Names Japanese Names An Ch’ing-hsü (An Qingxu) An Keisho An Lu-shan (An Lushan) An Rokuzan Chang-an (Zhangan) Shoan Chang Chieh (Zhang Jie) Cho Kai Chang Liang (Zhang Liang) Cho Ryo Chang Wen-chien (Zhang Wenjian) Cho Bunken Chao (Zhao), King Sho-o Chao Kao (Zhao Gao) Cho Ko Ch’en Chen (Chen Zhen) Chin Shin Ch’eng (Cheng), King Sei-o Cheng Hsüan (Zheng Xuan) Tei Gen Ch’eng-kuan (Chengguan) Chokan Chia-hsiang ( Jiaxiang) Kajo Chia-shang ( Jiashang) Kasho Chi-cha ( Jizha) Kisatsu Chieh ( Jie), King Ketsu-o Chieh Tzu-sui ( Jie Zisui) Kai Shisui Chien-chen ( Jianzhen) Ganjin Chih-chou (Zhizhou) Chishu Chih-i (Zhiyi) Chigi z Chih Po (Zhi Bo) Chi Haku Chih-tsang (Zhizang) Chizo Chih-tu (Zhidu) Chido Chih-yen (Zhiyan) Chigon Chih-yüan (Zhiyuan) Shion Ch’i Li-chi (Qi Liji) Ki Riki Ching-hsi ( Jingxi) Keikei Ching K’o ( Jing Ko) Kei Ka Ch’ing-liang (Qingliang) Shoryo Ching-shuang ( Jingshuang) Kyoso Chin-kang-chih ( Jingangzhi) Kongochi 1155 -1156 APPENDIX D Ch’in-tsung (Qinzong), Emperor Kinso-tei Chi-tsang ( Jizang) Kichizo Chou (Zhou), King Chu-o Chuang (Zhuang), King So-o Chuang Tzu (Zhuang Zi) Soshi Chu Fa-lan (Zhu Falan) Jiku Horan Ch’ung-hua (Chonghua) Choka Ch’u Shan-hsin (Chu Shanxin) Cho Zenshin q Chu Tao-sheng (Zhu Daosheng) Jiku Dosho Fa-ch’üan (Faquan) Hassen Fan K’uai (Fan Kuai) Han Kai y Fan Yü-ch’i (Fan Yuqi) Han Yoki Fa-pao -

SNOW LION PUBLI C'ltl Olss JANET BUDD 946 NOTTINGHAM DR

M 17 BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID ITHACA, NY 14851 Permit No. 746 SNOW LION PUBLI C'lTl OLsS JANET BUDD 946 NOTTINGHAM DR REDLANDS CA SNOW LION ORDER FROM OUR NEW TOLL FREE NUMBER NEWSLETTER & CATALOG 1-800-950-0313 SPRING 1992 SNOW LION PUBLICATIONS PO BOX 6483, ITHACA, NY 14851, (607)-273-8506 ISSN 1059-3691 VOLUME 7, NUMBER 2 Nyingma Transmission The Statement of His Holiness How 'The Cyclone' Came to the West the Dalai Lama on the Occasion by Mardie Junkins of the 33rd Anniversary of Once there lived a family in the practice were woven into their he danced on the rocks in an ex- village of Joephu, in the Palrong lives. If one of the children hap- plosion of radiant energy. Not sur- the Tibetan National Uprising valley of the Dhoshul region in pened to wake in the night, the prisingly, Tsa Sum Lingpa is Eastern Tibet. There was a father, father's continuous chanting could especially revered in the Dhoshul mother, two sisters, and two be heard. region of Tibet. As we commemorate today the brothers. Like many Tibetan fam- The valley was a magical place The oldest of the brothers was 33rd anniversary of the March ilies they were very devout. The fa- with a high mountain no one had nicknamed "The Cyclone" for his 10th Uprising in 1959,1 am more ther taught his children and the yet climbed and a high lake with enormous energy. He would run optimistic than ever before about children of the village the Bud- milky white water and yellow crys- up a nearby mountain to explore the future of Tibet. -

An Energetic Example of Bidirectional Sino-Japanese Esoteric Buddhist Transmission

religions Article From China to Japan and Back Again: An Energetic Example of Bidirectional Sino-Japanese Esoteric Buddhist Transmission Cody R. Bahir Independent Researcher, Palo Alto, CA 94303, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Sino-Japanese religious discourse, more often than not, is treated as a unidirectional phe- nomenon. Academic treatments of pre-modern East Asian religion usually portray Japan as the pas- sive recipient of Chinese Buddhist traditions, while explorations of Buddhist modernization efforts focus on how Chinese Buddhists utilized Japanese adoptions of Western understandings of religion. This paper explores a case where Japan was simultaneously the receptor and agent by exploring the Chinese revival of Tang-dynasty Zhenyan. This revival—which I refer to as Neo-Zhenyan—was actualized by Chinese Buddhist who received empowerment (Skt. abhis.eka) under Shingon priests in Japan in order to claim the authority to found “Zhenyan” centers in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Malaysia, and even the USA. Moreover, in addition to utilizing Japanese Buddhist sectarianism to root their lineage in the past, the first known architect of Neo-Zhenyan, Wuguang (1918–2000), used energeticism, the thermodynamic theory propagated by the German chemist Freidrich Wilhelm Ost- wald (1853–1932; 1919 Nobel Prize for Chemistry) that was popular among early Japanese Buddhist modernists, such as Inoue Enryo¯ (1858–1919), to portray his resurrected form of Zhenyan as the most suitable form of Buddhism for the future. Based upon the circular nature of esoteric trans- mission from China to Japan and back to the greater Sinosphere and the use of energeticism within Neo-Zhenyan doctrine, this paper reveals the sometimes cyclical nature of Sino-Japanese religious influence. -

The Fourteenth Dalai Lama's Oral Teachings on the Source of The

The Fourteenth Dalai Lama’s Oral Teachings on the Source of the Kālacakratantra Ronit Yoeli-Tlalim1 Warburg Institute, School of Advanced Studies, University of London THIS PAPER WILL PRESENT some rhetorical and discursive elements in oral versions of the history of the Kālacakratantra as currently presented by the Fourteenth Dalai Lama. Focusing on the definition of the Kālacakra’s “word of the Buddha” (buddha vacana), the paper will show how the Fourteenth Dalai Lama constructs an innovative version in his teachings, manifesting the relations between the esoteric tradition of Tibetan Buddhism and its contemporary religious milieux as it is being defined in exile. These rela- tions are apparent both in the information that is being taught and in the argumentation that constructs it. DEFINING THE KĀLACAKRATANTRA AS BUDDHA VACANA The issue of the source of the Kālacakratantra, or in other words, defin- ing the Kālacakratantra as buddha vacana, is of prime importance, not only for the study of the Kālacakra itself, but for the study of tantra in general.2 From the esoteric perspective connection with the Buddha is significant, not simply as a quasi-historical element, but as an element of practice, one that establishes a direct link with the possibility of enlightenment. According to the prevailing version in the Kālacakra tradition, the Buddha Śākyamuni taught the Kālacakratantra to King Suchandra of Shambhala. According to the Kālacakra tradition, it was at this occasion that the Buddha taught all of the tantra-s. From a traditional hermeneutical perspective the source of the teaching is of prime importance as it defines the fourfold relationship of: original au- thor/original audience // current teacher/current audience. -

Lowland Festivities in a Highland Society: Songkran in the Palaung Village of Pang Daeng Nai, Thailand1

➔CMU. Journal (2005) Vol. 4(1) 71 Lowland Festivities in a Highland Society: Songkran in the Palaung Village of Pang Daeng Nai, Thailand1 Sean Ashley* Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada *Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT In this article, I examine the celebration of Songkran in the Palaung village of Pang Daeng Nai in northern Thailand. The Palaung, a Mon-Khmer speaking people from Burma, have a long tradition of Theravada Buddhism which can be seen in a number of rituals and ceremonies associated with Songkran. While the Palaung have acquired both Buddhism and the Songkran festival from neighboring lowland populations, many practices and beliefs have taken on a local character in the process of transmission. In my paper, I discuss the similarities and differences between Palaung and lowland Tai Songkran ritual observances, particularly with regards to the annual song krau ceremony, a village-wide exorcism/blessing which coincides with the festival. Key words: Songkran festival, Song krau ceremony, Buddhism INTRODUCTION “True ‘Hill People’ are never Buddhists” (Leach, 1960). So wrote Edmund Leach in a paper describing the differences between highland minority groups in Burma and their lowland Tai2 and Burmese neighbors. This understanding of highlander culture is widespread and most studies on highland religion use Buddhism simply as grounds for comparison or ignore its influence on highland traditions altogether. In fact, both highlanders and lowlanders share an “animistic” worldview (Spiro, 1967; Terweil, 1994), but it is not my intention to deny that Theravada Buddhism, a ubiquitous facet of life in the lowlands, is largely absent from highland cultures. -

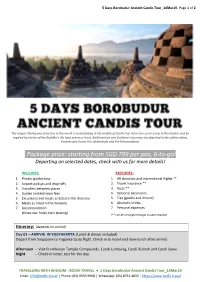

Starting from SGD 799 Per Pax, 6-To-Go! Departing on Selected Dates, Check with Us for More Details!

5 Days Borobudur Ancient Candis Tour_14Mar19- Page 1 of 2 The largest Mahayana structure in the world is located deep in the middle of South East Asia! Join us on a trip to Borobudur and be regaled by stories of the Buddha’s life (and previous lives), Bodhisattvas and Sudhana’s journeys (as depicted in the Lalitavistara, Avatamsaka Sutra, the Jatakamala and the Divyavadana). Package price: starting from SGD 799 per pax, 6-to-go! Departing on selected dates, check with us for more details! INCLUDES: EXCLUDES: 1. Private guided tour 1. All domestic and international flights ** 2. Airport pickups and drop-offs 2. Travel insurance ** 3. Transfers between places 3. Visas ** 4. Guides and entrance fees 4. Optional excursions 5. Excursions and meals as listed in the itinerary 5. Tips (guides and drivers) 6. Meals as listed in the itinerary 6. Alcoholic drinks 7. Accommodation 7. Personal expenses (three-star hotel, twin sharing) (** can be arranged through us upon request) Itinerary: (depends on arrival) Day 01 – ARRIVAL IN YOGYAKARTA (Lunch & dinner included) Depart from Singapore to Yogyakarta by flight. Check in to hotel and have lunch after arrival. Afternoon – Visit Prambanan Temple Compounds, Candi Lumbung, Candi Bubrah and Candi Sewu Night – Check-in hotel, rest for the day TRAVELLING WITH WISDOM - BODHI TRAVEL ● 5 Days Borobudur Ancient Candis Tour_14Mar19 Email: [email protected] │ Phone: (65) 6933 9908 │ WhatsApp: (65) 8751 4833 │ https://www.bodhi.travel 5 Days Borobudur Ancient Candis Tour_14Mar19- Page 2 of 2 Day 02 – CANDI BOROBUDUR -

BODHI TRAVEL 4 Days Borobudur Ancient Candis Tour 05Nov19

4 Days Borobudur Ancient Candis Tour_05Nov19- Page 1 of 2 The largest Mahayana structure in the world is located deep in the middle of South East Asia! Join us on a trip to Borobudur and be regaled by stories of the Buddha’s life (and previous lives), Bodhisattvas and Sudhana’s journeys (as depicted in the Lalitavistara, Avatamsaka Sutra, the Jatakamala and the Divyavadana). INCLUDES: EXCLUDES: 1. Private guided tour 1. Travel insurance ** 2. Airport pickups and drop-offs 2. Visas ** 3. Transfers between places (with air-cond) 3. Optional excursions 4. Guides and entrance fees 4. Tips (guides and drivers) 5. Excursions and meals as listed in the itinerary 5. Alcoholic drinks 6. Meals as listed in the itinerary 6. Personal expenses 7. Accommodation (four-star hotel, twin sharing) (** can be arranged through us upon request) 8. Round trip flight tickets (SIN – YOG) Itinerary: (this is our template itinerary, please let us if any customisation is needed) Day 01 – ARRIVAL IN YOGYAKARTA (Lunch & dinner included) AirAsia – departs daily – 1110hrs to 1230hrs (tentative) Depart from Singapore to Yogyakarta by flight. Have lunch after arrival. Afternoon – Visit Prambanan Temple Compounds, Candi Lumbung, Candi Bubrah and Candi Sewu Night – Check-in hotel and early rest Day 02 – CANDI BOROBUDUR (Breakfast@hotel, lunch & dinner included) Morning – Sunrise at Candi Borobudur (wake up at 4am), Guided tour at Candi Borobudur Afternoon – Visit Candi Pawon and Candi Mendut, Bike ride tour at village (optional) Night – Free and easy, rest for the day TRAVELLING WITH WISDOM - BODHI TRAVEL ● 4 Days Borobudur Ancient Candis Tour_05Nov19 Email: [email protected] │ WhatsApp: (65) 8751 4833 │ https://www.bodhi.travel 4 Days Borobudur Ancient Candis Tour_05Nov19- Page 2 of 2 Day 03 – VISIT TO MOUNT MERAPI (Breakfast@hotel, lunch & dinner included) Morning – Visit to Mount Merapi (Jeep ride) and House of Memories Afternoon – Return to Yogyakarta (max. -

Bhinneka Tunggal Ika” in Forming Harmony of Multicultural Society

Unconsidered Ancient Treasure, Struggling the Relevance of Fundamental Indonesia Nation Philosophie “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika” in Forming Harmony of Multicultural Society Fithriyah Inda Nur Abida, State University of Surabaya, Indonesia Dewi Mayangsari, Trunojoyo University, Indonesia Syafiuddin Ridwan, Airlangga University, Indonesia The Asian Conference on Cultural Studies Official Conference Proceedings 0139 Abstract Indonesia is a multicultural country consists of hundreds of distinct native ethnic, racist, and religion. Historically, the Nation was built because of the unitary spirit of its components, which was firmly united and integrated to make up the victory of the Nation. The plurality become advantageous when it reach harmony as reflected in the National motto “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika”. However, plurality also issues social conflict easily. Ever since its independence, the scent of disintegration has already occurred. However, in the last decade, social conflicts with a variety of backgrounds are intensely happened, especially which is based on religious tensions. The conflict arises from differences in the interests of various actors both individuals and groups. It is emerged as a fractional between the groups in the society or a single group who wants to have a radically changes based on their own spiritual perspective. Pluralism is not a cause of conflict, but the orientation which is owned by each of the components that determine how they’re viewing themselves psychologically in front of others. “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika” is an Old Javanese phrase of the book “Sutasoma” written by Mpu Tantular during the reign of the Majapahit sometime in the 14th century, which literally means “Diverse, yet united” or perhaps more poetically in English: Unity in Diversity. -

EMERGENCY SHELTER REQUIRED Legend

110°0'0"E 110°12'0"E 110°24'0"E 110°36'0"E 110°48'0"E KOTA BOYOLALI SURAKARTA Pucang Miliran Tegalmulyo Sudimoro S S Tulung " " Balerante Daleman 0 0 Sidomulyo MAGELANG Mundu ' ' Tlogowatu Tegalgondo Kemiri Gedongjetis Cokro 6 6 Kayumas Beji Bolali Polanharjo Wadung 3 3 Sedayu Segaran Dalangan Kebonharjo ° ° Pandanan Teloyo Turi Pomah Wangen Kranggan Getas Sukorejo 7 7 Majegan Keprabon Kemalang Bandungan Karanglo Gatak Mendak Sekaran Kendalsari Socokangsi Kiringan Jeblog De lan ggu Boto KLATEN Gempol Turus Krecek Bentangan Kingkang Panggang Glagah Bonyokan Pondok Nganjat Sabrang Tlobong Dompol Kauman Karang Lumbung Kerep SLEMAN Jatinom Gledeg Pundungan Jurangjero Ngemplak Ngaran Banaran Wonosari Bengking Jatinom Gunting Bawukan Jiwan Glagah Wangi Talun Karanganom Jetis Ju w irin g Logede Kunden Randulanang Karangan Trasan Juwiring Carikan Ngemplak Kemalang Kahuman Jungkare Jaten Kalibawang Cangkringan Gemampir Kwarasan Taji Samigaluh Kepurun Seneng Tempursari Troso Bulurejo Tanjung Donokerto Blanceran Bolopleret Manisrenggo Kanoman Blimbing Ngawonggo Juwiran Kenaiban Sapen Keputran Ngawen Jambu Tambak Rejo Pakem Jagalan Ceper Tlogorandu Serenan Duwet Ngawen Mayungan Kulon Lemahireng Jetis Harjo Binangun Karangnongko Dlimas Kaligawe Kadilajo Jetis Belang Jombor Kurung Leses Gergunung Kebonalas Sukorini Karangduren Wetan Pokak Cetan Pedan Manjung Klaten Utara Kalangan Tegalampel Triharjo Banyuaeng Malangjiwan Bareng Kujon Jambu Sobayan Karangwungu Babadan Bendan Gumul Sekarsuli Mlese Pandowo Suko Kranggan Kidul Sentono Karangtalun Tempel