Dr Joo-Cheong Tham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review Essay Open Chambers: High Court Associates and Supreme Court Clerks Compared

REVIEW ESSAY OPEN CHAMBERS: HIGH COURT ASSOCIATES AND SUPREME COURT CLERKS COMPARED KATHARINE G YOUNG∗ Sorcerers’ Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court by Artemus Ward and David L Weiden (New York: New York University Press, 2006) pages i–xiv, 1–358. Price A$65.00 (hardcover). ISBN 0 8147 9404 1. I They have been variously described as ‘junior justices’, ‘para-judges’, ‘pup- peteers’, ‘courtiers’, ‘ghost-writers’, ‘knuckleheads’ and ‘little beasts’. In a recent study of the role of law clerks in the United States Supreme Court, political scientists Artemus Ward and David L Weiden settle on a new metaphor. In Sorcerers’ Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court, the authors borrow from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s famous poem to describe the transformation of the institution of the law clerk over the course of a century, from benign pupilage to ‘a permanent bureaucracy of influential legal decision-makers’.1 The rise of the institution has in turn transformed the Court itself. Nonetheless, despite the extravagant metaphor, the authors do not set out to provide a new exposé on the internal politics of the Supreme Court or to unveil the clerks (or their justices) as errant magicians.2 Unlike Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong’s The Brethren3 and Edward Lazarus’ Closed Chambers,4 Sorcerers’ Apprentices is not pitched to the public’s right to know (or its desire ∗ BA, LLB (Hons) (Melb), LLM Program (Harv); SJD Candidate and Clark Byse Teaching Fellow, Harvard Law School; Associate to Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG, High Court of Aus- tralia, 2001–02. -

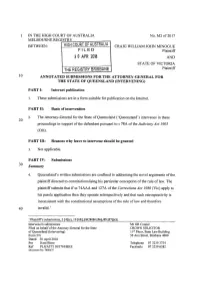

3 0 APR 2018 and STATE of VICTORIA the REGISTRY BRISBANE Plaintiff 10 ANNOTATED SUBMISSIONS for the ATTORNEY-GENERAL for the STATE of QUEENSLAND (INTERVENING)

IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA No. M2 of2017 MELBOURNEREG~IS~T~R~Y--~~~~~~~ BETWEEN: HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA CRAIG WILLIAM JOHN MINOGUE FILED Plaintiff 3 0 APR 2018 AND STATE OF VICTORIA THE REGISTRY BRISBANE Plaintiff 10 ANNOTATED SUBMISSIONS FOR THE ATTORNEY-GENERAL FOR THE STATE OF QUEENSLAND (INTERVENING) PART I: Internet publication I. These submissions are in a form suitable for publication on the Internet. PART 11: Basis of intervention 2. The Attorney-General for the State of Queensland ('Queensland') intervenes in these 20 proceedings in support of the defendant pursuant to s 78A of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). PART Ill: Reasons why leave to intervene should be granted 3. Not applicable. PART IV: Submissions 30 Summary 4. Queensland's written submissions are confined to addressing the novel arguments of the plaintiff directed to constitutionalising his particular conception of the rule of law. The plaintiff submits that if ss 74AAA and 127A ofthe Corrections Act 1986 (Vie) apply to his parole application then they operate retrospectively and that such retrospectivity is inconsistent with the constitutional assumptions of the rule of law and therefore 40 invalid. 1 1 Plaintiffs submissions, 2 [4](c), 19 [68]; (SCB 84(36), 85(37)(c)). Intervener's submissions Mr GR Cooper Filed on behalf of the Attorney-General for the State CROWN SOLICITOR of Queensland (Intervening) 11th Floor, State Law Building Form 27c 50 Ann Street, Brisbane 4000 Dated: 30 April2018 Per Kent Blore Telephone 07 3239 3734 Ref PL8/ATT110/3710/BKE Facsimile 07 3239 6382 Document No: 7880475 5. Queensland's primary submission is that ss 74AAA and 127 A ofthe Corrections Act do not operate retrospectively as they merely prescribe criteria for the Board to apply in the future. -

Murdoch University School of Law Michael Olds This Thesis Is

Murdoch University School of Law THE STREAM CANNOT RISE ABOVE ITS SOURCE: THE PRINCIPLE OF RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT INFORMING A LIMIT ON THE AMBIT OF THE EXECUTIVE POWER OF THE COMMONWEALTH Michael Olds This thesis is presented in fulfilment of the requirements of a Bachelor of Laws with Honours at Murdoch University in 2016 Word Count: 19,329 (Excluding title page, declaration, copyright acknowledgment, abstract, acknowledgments and bibliography) DECLARATION This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any other University. Further, to the best of my knowledge or belief, this thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the text. _______________ Michael Olds ii COPYRIGHT ACKNOWLEDGMENT I acknowledge that a copy of this thesis will be held at the Murdoch University Library. I understand that, under the provisions of s 51(2) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), all or part of this thesis may be copied without infringement of copyright where such reproduction is for the purposes of study and research. This statement does not signal any transfer of copyright away from the author. Signed: ………………………………… Full Name of Degree: Bachelor of Laws with Honours Thesis Title: The stream cannot rise above its source: The principle of Responsible Government informing a limit on the ambit of the Executive Power of the Commonwealth Author: Michael Olds Year: 2016 iii ABSTRACT The Executive Power of the Commonwealth is shrouded in mystery. Although the scope of the legislative power of the Commonwealth Parliament has been settled for some time, the development of the Executive power has not followed suit. -

Inquiry Into Government Advertising and Accountability with Amendments to Term of Reference (A)

The Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee Government advertising and accountability December 2005 © Commonwealth of Australia 2005 ISBN 0 642 71593 9 This document is prepared by the Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee and printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Parliament House, Canberra. Members of the Committee Senator Michael Forshaw (Chair) ALP, NSW Senator John Watson (Deputy Chair) LP, TAS Senator Carol Brown ALP, TAS Senator Mitch Fifield LP, NSW Senator Claire Moore ALP, QLD Senator Andrew Murray AD, WA Substitute member for this inquiry Senator Kim Carr ALP, VIC (replaced Senator Claire Moore from 22 June 2005) Former substitute member for this inquiry Senator Andrew Murray AD, WA (replaced Senator Aden Ridgeway 30 November 2004 to 30 June 2005) Former members Senator George Campbell (discharged 1 July 2005) Senator the Hon William Heffernan (discharged 1 July 2005) Senator Aden Ridgeway (until 30 June 2005) Senator Ursula Stephens (1 July to 13 September 2005) Participating members Senators Abetz, Bartlett, Bishop, Boswell, Brandis, Bob Brown, Carr, Chapman, Colbeck, Conroy, Coonan, Crossin, Eggleston, Evans, Faulkner, Ferguson, Ferris, Fielding, Fierravanti-Wells, Joyce, Ludwig, Lundy, Sandy Macdonald, Mason, McGauran, McLucas, Milne, Moore, O'Brien, Parry, Payne, Ray, Sherry, Siewert, Stephens, Trood and Webber. Secretariat Alistair Sands Committee Secretary Sarah Bachelard Principal Research Officer Matt Keele Research Officer Alex Hodgson Executive Assistant Committee address Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee SG.60 Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Tel: 02 6277 3530 Fax: 02 6277 5809 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://www.aph.gov.au/senate_fpa iii iv Terms of Reference On 18 November 2004, the Senate referred the following matter to the Finance and Public Administration References Committee for inquiry and report by 22 June 2005. -

Judicial Activism: Power Without Responsibility? No, Appropriate Activism Conforming to Duty

—M.U.L.R- 09 Kirby (prepress complete)02.doc —— page 576 of 18 JUDICIAL ACTIVISM: POWER WITHOUT RESPONSIBILITY? NO, APPROPRIATE ACTIVISM CONFORMING TO DUTY THE HON JUSTICE MICHAEL KIRBY AC CMG∗ [This article was originally delivered as a contribution to a conversazione held in 2005 at the Melbourne University Law School in which judges, legal academics, journalists and others discussed issues of ‘judicial activism’. Developing ideas expressed in his 2003 Hamlyn Lectures on the same topic, the author asserts that creativity has always been part of the judicial function and duty in common law countries. He illustrates this statement by reference to the Australian Communist Party Case, and specifically the reasons of Dixon J, often cited as the exemplar of judicial restraint. He suggests that ‘judicial activism’ has become code language for denouncing important judicial decisions with which conservative critics disagree. By reference to High Court decisions on the meaning of ‘jury’ in s 80 of the Australian Constitution and cases on constitutional free speech, legal defence of criminal accused and native title, he explains the necessities and justifications of some judicial creativity. He illustrates the dangers of a mind-lock of strict textualism and the futility of media and political bullying of judges who simply do their duty. Finally he calls for greater civility in the language of discourse on the proper limits of judicial decision-making.] CONTENTS I Nostalgic Thoughts................................................................................................ -

Australian Guide to Legal Citation V4

4 Australian Guide to Legal Citation Fourth Edition USTRALIAN UIDE A G TO LEGAL CITATION Fourth Edition Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc in collaboration with Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc Melbourne 2018 Published and distributed by the Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc in collaboration with the Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Australian Guide to Legal Citation / Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc., Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc. 4th ed. ISBN 9780646976389. Bibliography. Includes index. Citation of legal authorities - Australia - Handbooks, manuals, etc. 808.06634 First edition 1998 Second edition 2002 Third edition 2010, 2011 (with minor corrections), 2012 (with minor corrections) Published by: Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc Reg No A0017345F · ABN 21 447 204 764 Melbourne University Law Review Telephone: (+61 3) 8344 6593 Melbourne Law School Facsimile: (+61 3) 9347 8087 The University of Melbourne Email: <[email protected]> Victoria 3010 Australia Website: <http://www.mulr.unimelb.edu.au> Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc Reg No A0046334D · ABN 86 930 725 641 Melbourne Journal of International Law Telephone: (+61 3) 8344 7913 Melbourne Law School Facsimile: (+61 3) 8344 9774 The University of Melbourne Email: <[email protected]> Victoria 3010 Australia Website: <http://www.mjil.unimelb.edu.au> © 2018 Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc and Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc. This work is protected by the laws of copyright. Except for any uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) or equivalent overseas legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced, in any manner or in any medium, without the written permission of the publisher. -

Government Communication in Australia Edited by Sally Young Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-68171-1 - Government Communication in Australia Edited by Sally Young Index More information Index ABC, xxxii Association of Non-English Speaking Media Watch, 142 Background Women of Australia, 267 radio broadcasting of parliament, 73 Association of Women’s Organisations radio youth network Triple J, 277 Conference, 268 Abetz, Eric, 161, 269 Atkins, Dennis, 132 accessibility, xxix Atkinson, Joe, 92 accountability, 20, 25, 84, 230, 232 Attorney-General’s Department, 12, 212 information flow and, 37 Auditor-General, 20, 45 in the public service, 49 advertising guidelines, 33, 195, 204, 242 ACT government, 235, see also Stanhope, Jon Australia ‘Canberra Connect’, 238 citizens and online communication, Chief Minister’s Talkback, 245 176–8 Community Cabinet, 249 compulsory voting, 174 ACTU-ALP Accord, 55 Constitution, 28, 68 ACTV v Commonwealth, 28 e-government, 166 advertising, regulation of, 39 evaluation of government communication, Advertising Standards Council, 33 232–4 advocacy, 164, 256, 257–8 federal system, xxv, 6 Akerman, Piers, 87, 141 geographical distances, xxv Albrechtsen, Janet, 142 government advertising in, 181–203 Allan, Tim, 107 government communication online, Althusser, Louis, 217 161–80 Amnesty International, 281 innovation in government communication, Anderson, Lori, 163 229–54 aNiMaLS, 9, 134 national belonging, 216–22, 223 Animals II, 10 national identity, 262 ANSTO campaign, 121, 125 service delivery by the voluntary sector, 10, Anti-Cancer Councils, 190 255 anti-terrorism advertising, -

The Momcilovic Question: Does the Rule of Law Limit the Capacity of the New South Wales Legislature?

THE MOMCILOVIC QUESTION: DOES THE RULE OF LAW LIMIT THE CAPACITY OF THE NEW SOUTH WALES LEGISLATURE? MARTIN ROLAND HILL SYDNEY LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO FULFILL REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LAWS ABSTRACT This thesis seeks to ascertain whether the rule of law limits the legislative power of State legislatures (a question posted in Momcilovic v The Queen (2011) 245 CLR 1). It argues that the rule of law, understood as a legal principle, is not presently recognised as a constraint on the capacity of the New South Wales Legislature. It further argues that it is unlikely that the rule of law will be recognised as such a constraint. This thesis starts with consideration of the concept of the rule of law. It surveys conceptions of the rule of law that have informed Australian jurists and conceptions advanced by those jurists. It does so to show how theoretical conceptions have informed judicial consideration of the rule of law. It also surveys the aspects and requirements of the rule of law that have been recognised by the High Court of Australia. It demonstrates that those aspects correspond to the theoretical conceptions. It also distinguishes those aspects and requirements connected to legality from other identified aspects and requirements. This thesis then shows that the rule of law has not been recognised as a constraint on the power conferred on the New South Wales Legislature by the Constitution Act 1902 (NSW). It examines the constraints imposed by the Constitution Act 1902 and the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution. -

Australian Guide to Legal Citation

4 Australian Guide to Legal Citation Fourth Edition AUSTRALIAN GUIDE TO LEGAL CITATION Fourth Edition Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc in collaboration with Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc Melbourne 2018 Published and distributed by the Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc in collaboration with the Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Australian Guide to Legal Citation / Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc., Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc. 4th ed. ISBN 9780646976389. Bibliography. Includes index. Citation of legal authorities - Australia - Handbooks, manuals, etc. 808.06634 First edition 1998 Second edition 2002 Third edition 2010, 2011 (with minor corrections), 2012 (with minor corrections) Fourth edition 2018, 2019 (with minor corrections), 2020 (with minor corrections) Published by: Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc Reg No A0017345F · ABN 21 447 204 764 Melbourne University Law Review Telephone: (+61 3) 8344 6593 Melbourne Law School Facsimile: (+61 3) 9347 8087 The University of Melbourne Email: <[email protected]> Victoria 3010 Australia Website: <http://www.law.unimelb.edu.au/mulr> Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc Reg No A0046334D · ABN 86 930 725 641 Melbourne Journal of International Law Telephone: (+61 3) 8344 7913 Melbourne Law School Facsimile: (+61 3) 8344 9774 The University of Melbourne Email: <[email protected]> Victoria 3010 Australia Website: <http://www.law.unimelb.edu.au/mjil> © 2018 Melbourne University Law Review Association Inc and Melbourne Journal of International Law Inc. This work is protected by the laws of copyright. Except for any uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) or equivalent overseas legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced, in any manner or in any medium, without the written permission of the publisher. -

Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth Conference of the Samuel Griffith Society

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Twenty-five Proceedings of the Twenty-fifth Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society Rydges, North Sydney — November 2013 © Copyright 2015 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. Contents Introduction Julian Leeser The Fifth Sir Harry Gibbs Memorial Oration The Honourable Dyson Heydon Sir Samuel Griffith as Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia Chapter One Greg Craven A Federalist Agenda for the Government’s White Paper Chapter Two Anne Twomey Money, Power and Pork-Barrelling: Expenditure of Public Money without Parliamentary Authorisation Chapter Three Keith Kendall Comparative Federal Income Tax Chapter Four J. B. Paul Independents and Minor Parties in the Commonwealth Parliament Chapter Five Ian McAllister Reforming the Senate Electoral System Chapter Six Malcolm Mackerras Electing the Australian Senate: In Defence of the Present System Chapter Seven Gim Del Villar TheKable Case i Chapter Eight Nicholas Cater The Human Rights Commission: A Failed Experiment Chapter Nine Damien Freeman Meagher, Mabo and Patrick White’s tea-cosy – 20 Years On Chapter Ten Dean Smith Double Celebration: The Referendum that did not Proceed Chapter Eleven Bridget Mackenzie Rigging the Referendum: How the Rudd Government Slanted the Playing Field for Constitutional Change: The Abuse of the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act Chapter Twelve The Honourable Gary Johns Recognition: History Yes, Culture No Contributors ii Introduction Julian Leeser The 25th Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society was held in Sydney in November 2013. The 2013 Conference was scheduled to be held in Melbourne. It was moved to Sydney. This was not, as was rumoured, because our board member, Richard Court, agreed with the former Prime Minister, Paul Keating, that “if you are not living in Sydney you are just camping out.” It was rather because the Spring racing carnival would have needlessly increased accommodation costs at that time of the year in Melbourne. -

Papers on Parliament Lectures in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series, and Other Papers

Papers on Parliament Lectures in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series, and other papers Number 59 April 2013 Published and printed by the Department of the Senate Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031–976X Published by the Department of the Senate, 2013 ISSN 1031–976X Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Department of the Senate. Edited by Paula Waring All editorial inquiries should be made to: Assistant Director of Research Research Section Department of the Senate PO Box 6100 Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (02) 6277 3164 Email: [email protected] To order copies of Papers on Parliament On publication, new issues of Papers on Parliament are sent free of charge to subscribers on our mailing list. If you wish to be included on that mailing list, please contact the Research Section of the Department of the Senate at: Telephone: (02) 6277 3074 Email: [email protected] Printed copies of previous issues of Papers on Parliament may be provided on request if they are available. Past issues are available online at: http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Senate/Research_and_Education/pops Contents Liberal Women in Parliament: What Do the Numbers Tell Us and Where to from Here? 1 Margaret Fitzherbert The Scope of Executive Power 15 Cheryl Saunders Will Dyson: Australia’s Radical Genius 35 Ross McMullin How Should Elected Members Learn Parliamentary Skills? 59 Ken Coghill ‘But Once in a History’: Canberra’s Foundation Stones and Naming Ceremonies, 12 March 1913 83 David Headon Paying for Parliament: Do We Get What We Pay For? Lessons from Canada 101 Christopher Kam and Faruk Pinar Is It Futile to Petition the Australian Senate? 129 Paula Waring iii Contributors Margaret Fitzherbert is Senior Manager, Communications and Government, at the Civic Group and the author of Liberal Women: Federation to 1949 (2004) and So Many Firsts: Liberal Women from Enid Lyons to the Turnbull Era (2009). -

The Parameters of Constitutional Change*

THE PARAMETERS OF CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE* THE HON SIR GERARD BRENNAN AC KBE** I INTRODUCTION Seven years ago, we celebrated the centenary of our Constitution, observing how well it has served us in times of war and in times of peace; in times of prosperity and in times of poverty. Six Colonies have grown into an independent nation, free of Imperial legislative power, conducting our own affairs and responsible for our own safekeeping. Our Constitution has been the framework of a stable democracy, governed by the rule of law and modelled somewhat loosely on the Westminster system. The Constitution could be improved in a number of respects which were identifi ed by the Constitutional Commission’s Report in 1988. They relate chiefl y to the composition, tenure and powers of the Parliament. It could be improved by acknowledging the dignity of our indigenous peoples. Changes of these kinds can be effected only by referendum, but structural changes can occur and have occurred without signifi cant change in the constitutional text. The last 100 years have seen a transformation of our form of government. A facilitator of change has been the High Court, as Alfred Deakin foretold when he introduced the Bill for the Judiciary Act in 1903: the nation lives, grows, and expands. Its circumstances change, its needs alter, and its problems present themselves with new faces. The organ of the national life, which preserving the union is yet able from time to time to transfuse into it the fresh blood of the living present, is the Judiciary. ... It is as one of the organs of Government which enables the Constitution to grow and to be adapted to the changeful necessities and circumstances of generation after generation that the High Court operates.1 The High Court has not been the only organ of government that has responded to changing circumstances.