Shadow-Elite-S.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capital Punishment in Illinois in the Aftermath of the Ryan Commutations

Northwestern University School of Law Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Working Papers 2010 CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN ILLINOIS IN THE AFTERMATH OF THE RYAN COMMUTATIONS: REFORMS, ECONOMIC REALITIES, AND A NEW SALIENCY FOR ISSUES OF COST Leigh Buchanan Bienen Northwestern University School of Law, [email protected] Repository Citation Bienen, Leigh Buchanan, "CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN ILLINOIS IN THE AFTERMATH OF THE RYAN COMMUTATIONS: REFORMS, ECONOMIC REALITIES, AND A NEW SALIENCY FOR ISSUES OF COST" (2010). Faculty Working Papers. Paper 118. http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/facultyworkingpapers/118 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/10/10004-0001 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 100, No. 4 Copyright © 2010 by Northwestern University, School of Law Printed in U.S.A. CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN ILLINOIS IN THE AFTERMATH OF THE RYAN COMMUTATIONS: REFORMS, ECONOMIC REALITIES, AND A NEW SALIENCY FOR ISSUES OF COST LEIGH B. BIENEN Perhaps most telling is the view of Professor Joseph Hoffman, someone who has devoted enormous time and energy to death penalty reform, spearheading death penalty reform efforts in both Illinois and Indiana and serving as Co-Chair and Reporter for the Massachusetts Governor‘s Council on Capital Punishment. Hoffman served as a member of an advisory group to discuss an earlier draft of this paper, and he strongly expressed the view that seeking reform of capital punishment in the political realm is futile. -

Procurement Services

FOIA Request Log - Procurement Services REQUESTOR NAME ORGANIZATION Allan R. Popper Linguard, Inc. Maggie Kenney n/a Leigh Marcotte n/a Jeremy Lewno Bobby's Bike Hike Diane Carbonara Fox News Chicago Chad Dobrei Tetra Tech EM, Inc James Brown AMCAD Laura Waxweiler n/a Robert Jones Contractors Adjustment Company Robert Jones Contractors Adjustment Company Allison Benway Chico & Nunes, P.C. Rey Rivera Humboldt Construction Bennett Grossman Product Productions/Space Stage Studios Robert Jones Contractors Adjustment Company Larry Berman n/a Arletha J. Newson Arletha's Aua Massage Monica Herrera Chicago United Industries James Ziegler Stone Pogrund & Korey LLC Bhav Tibrewal n/a Rey Rivera CSI 3000 Inc. Page 1 of 843 10/03/2021 FOIA Request Log - Procurement Services DESCRIPTION OF REQUEST Copy of payment bond for labor & material for the Chicago Riverwalk, South side of Chicago River between State & Michigan Ave. How to find the Department of Procurement's website A copy of disclosure 21473-D1 Lease agreement between Bike Chicago & McDonald's Cycle center (Millennium Park Bike Station) All copies of contracts between Xora and the City of Chicago from 2000 to present. List of City Depts. that utilized the vendor during time frame. The technical and cost proposals & the proposal evaluation documents for the proposal submitted by Beck Disaster Recovery. the proposal evaluation documents for the proposal submitted by Tetra Tech EM, Inc and the contract award justification document Copies of the IBM/Filenet and Crowe proposals for Spec 68631 Copies -

Press Galleries* Rules Governing Press Galleries

PRESS GALLERIES* SENATE PRESS GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–316, phone 224–0241 Director.—S. Joseph Keenan Deputy Director.—Joan McKinney Media Coordinators: Elizabeth Crowley Wendy A. Oscarson-Kirchner Amy H. Gross James D. Saris HOUSE PRESS GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–315, phone 225–3945 Superintendent.—Jerry L. Gallegos Deputy Superintendent.—Justin J. Supon Assistant Superintendents: Ric Andersen Drew Cannon Molly Cain Laura Reed STANDING COMMITTEE OF CORRESPONDENTS Maureen Groppe, Gannett Washington Bureau, Chair Laura Litvan, Bloomberg News, Secretary Alan K. Ota, Congressional Quarterly Richard Cowan, New York Times Andrew Taylor, Reuters Lisa Mascaro, Las Vegas Sun RULES GOVERNING PRESS GALLERIES 1. Administration of the press galleries shall be vested in a Standing Committee of Cor- respondents elected by accredited members of the galleries. The Committee shall consist of five persons elected to serve for terms of two years. Provided, however, that at the election in January 1951, the three candidates receiving the highest number of votes shall serve for two years and the remaining two for one year. Thereafter, three members shall be elected in odd-numbered years and two in even-numbered years. Elections shall be held in January. The Committee shall elect its own chairman and secretary. Vacancies on the Committee shall be filled by special election to be called by the Standing Committee. 2. Persons desiring admission to the press galleries of Congress shall make application in accordance with Rule VI of the House of Representatives, subject to the direction and control of the Speaker and Rule 33 of the Senate, which rules shall be interpreted and administered by the Standing Committee of Correspondents, subject to the review and an approval by the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration. -

Read Full Journal Issue

Children’s Legal Rights Journal Loyola University Chicago School of Law Civitas ChildLaw Center Editor-in-Chief Sarah Sallen Managing Editor Articles Editor Lisa Hendrix Kevin Tomczyk Publications Editor Features Editor Ashley Jaconetti Addison Kuhn Solicitations Editor Assistant Solicitations Editor Brenda McKinney Alana O’Reilly Symposium Editor Assistant Symposium Editor Jennifer Schufreider Sean Mussey Senior Editors Annie Park Brittany Francois Christine Dadourian Nichele Marks Samantha Thoma Junior Editors Dan Baczynski Erin Keeley Caitlin Sharrow Rachel Basset Raydia Martin Christina Spieza Caitlin Cipri Ellen Porter Natasha Townes Amanda Crews Rupa Ramadurai Maria Vuolo Amy Gilbert Christina Rizen Amanda Walsh Elizabeth Gresk Thalia Roussos Erin Wenger Katherine Hinkle Melina Rozzisi Liz Youakim Sarah Jin Elizabeth Scannel Advisors Professor Diane Geraghty Faculty Advisor, Loyola University Chicago School of Law Howard Davidson Director, ABA Center on Children and the Law Kendall Marlowe Executive Director, National Association of Counsel for Children Cite as 33 CHILD. LEGAL RTS. J. __ (2013) Volume 33, Number1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Spring 2013 Undocumented Children and Families in America: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of Challenges and Emerging Issues By Diane Geraghty ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Improving How Our Child Welfare System Addresses Children, Youth, and Families -

Press Galleries* Rules Governing Press

PRESS GALLERIES* SENATE PRESS GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–316, phone 224–0241 Director.—S. Joseph Keenan Deputy Director.—Joan McKinney Media Coordinators: Michael Cavaiola Wendy A. Oscarson Amy H. Gross James D. Saris HOUSE PRESS GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–315, phone 225–3945 Superintendent.—Jerry L. Gallegos Deputy Superintendent.—Justin J. Supon Assistant Superintendents: Ric Andersen Drew Cannon Molly Cain Laura Reed STANDING COMMITTEE OF CORRESPONDENTS Bill Walsh, Times-Picayne, Chair Thomas Ferraro, Reuters, Secretary Susan Ferrechio, Congressional Quarterly Carl Hulse, New York Times Andrew Taylor, Associated Press RULES GOVERNING PRESS GALLERIES 1. Administration of the press galleries shall be vested in a Standing Committee of Cor- respondents elected by accredited members of the galleries. The Committee shall consist of five persons elected to serve for terms of two years. Provided, however, that at the election in January 1951, the three candidates receiving the highest number of votes shall serve for two years and the remaining two for one year. Thereafter, three members shall be elected in odd-numbered years and two in even-numbered years. Elections shall be held in January. The Committee shall elect its own chairman and secretary. Vacancies on the Committee shall be filled by special election to be called by the Standing Committee. 2. Persons desiring admission to the press galleries of Congress shall make application in accordance with Rule VI of the House of Representatives, subject to the direction and control of the Speaker and Rule 33 of the Senate, which rules shall be interpreted and administered by the Standing Committee of Correspondents, subject to the review and an approval by the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration. -

Press Galleries* Rules Governing Press

PRESS GALLERIES * SENATE PRESS GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–316, phone 224–0241 Director.—S. Joseph Keenan Deputy Director.—Joan McKinney Senior Media Coordinators: Amy H. Gross Kristyn K. Socknat Media Coordinators: James D. Saris Wendy A. Oscarson-Kirchner Elizabeth B. Crowley HOUSE PRESS GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–315, phone 225–3945 Superintendent.—Jerry L. Gallegos Deputy Superintendent.—Justin J. Supon Assistant Superintendents: Ric Anderson Laura Reed Drew Cannon Molly Cain STANDING COMMITTEE OF CORRESPONDENTS Thomas Burr, The Salt Lake Tribune, Chair Joseph Morton, Omaha World-Herald, Secretary Jim Rowley, Bloomberg News Laurie Kellman, Associated Press Brian Friel, Bloomberg News RULES GOVERNING PRESS GALLERIES 1. Administration of the press galleries shall be vested in a Standing Committee of Cor- respondents elected by accredited members of the galleries. The Committee shall consist of five persons elected to serve for terms of two years. Provided, however, that at the election in January 1951, the three candidates receiving the highest number of votes shall serve for two years and the remaining two for one year. Thereafter, three members shall be elected in odd-numbered years and two in even-numbered years. Elections shall be held in January. The Committee shall elect its own chairman and secretary. Vacancies on the Committee shall be filled by special election to be called by the Standing Committee. 2. Persons desiring admission to the press galleries of Congress shall make application in accordance with Rule VI of the House of Representatives, subject to the direction and control of the Speaker and Rule 33 of the Senate, which rules shall be interpreted and administered by the Standing Committee of Correspondents, subject to the review and an approval by the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration. -

ADVANCE SERVICES Franklin, Massachusetts (508) 520-2076 10

1 - 58 H A R V A R D U N I V E R S I T Y JOHN F. KENNEDY SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT JOAN SHORENSTEIN CENTER ON THE PRESS, POLITICS AND PUBLIC POLICY THE GOLDSMITH AWARDS Wednesday March 17, 2004 John F. Kennedy, Jr. Forum Littauer Building Kennedy School of Government Cambridge, Massachusetts BEFORE: ALEX JONES Director Joan Shorenstein Center on Press Politics and Public Policy Kennedy School of Government ADVANCE SERVICES Franklin, Massachusetts (508) 520-2076 2 1 I N D E X 2 OPENING REMARKS PAGE 3 Joseph S. Nye, Jr. 3 4 Alex Jones 4 5 6 GOLDSMITH BOOK PRIZES 7 Tom Patterson 8 8 Scott Althaus 10 9 Paul Kellstedt 12 10 Timothy Carlson 14 11 12 GOLDSMITH PRIZE FOR INVESTIGATIVE REPORTING 13 Alex Jones 16 14 Lowell Bergman 32 15 David Rummell 33 16 Michael Oreskes 34 17 18 GOLDSMITH CAREER AWARD FOR EXCELLENCE IN JOURNALISM 19 Fred Schauer 35 20 Linda Greenhouse 37 21 QUESTION AND COMMENT SEGMENT 22 Laura Meckler 49 23 Nick Smith 50 24 Richard Sobol 53 ADVANCE SERVICES Franklin, Massachusetts (508) 520-2076 3 1 Ravi Naidoo 54 ADVANCE SERVICES Franklin, Massachusetts (508) 520-2076 4 1 E V E N I N G S E S S I O N 2 (8:07 p.m.) 3 MR. NYE: Good evening, I'm Joe Nye, Dean of 4 the Kennedy School, and it's my pleasure to welcome you 5 to the 12th Annual Goldsmith Awards, which recognize 6 excellence in political journalism. The Goldsmith 7 Awards include a prize for investigative reporting, two 8 book prizes and a career award for excellence in 9 journalism. -

[IRE Journal Issue Irejournaljanfeb2008; Fri Jan 11

JUNE 5-8 REGISTRATION You can register for this conference online at www.ire.org/training/miami08. To attend this conference, HOST: you must be an IRE member The Miami Herald through July 1, 2008. and El Nuevo Herald Memberships are nonrefundable. Early-bird registration closes May 19. e best in the busine will gather for panels REGISTRATION FEE: workshops and special presentations about (main conference days) $165 Professional/Academic/ Associate/Retiree covering public safety, courts, national $100 Student security, the military, busine, education, CAR DAY – optional: Thursday, June 5 (requires additional fee) local government and much more. $50 Professional/Academic/ Associate/Retiree $35 Student Visit ww.ire.org/training/miami08 BLUES BASH for more information and updates. Thursday, June 5 at 7 p.m. Advance tickets are $20. IRE offers several programs to help women, members of minority Ticket prices on site, groups, college students and journalists from small news organiza- if available, will be higher. tions attend the conference. Fellowships typically provide a one-year Limit of 2 tickets per registrant. membership, registration fees, and reimbursement for hotel and travel costs. See details at www.ire.org/training/fellowships.html. Conference Hotel Apply by April 7 for the Miami conference. contact conference InterContinental Miami If you If you have hotel or general conference questions www.ichmiami.com coordinator Stephanie Sinn, [email protected], 573-882-8969.Green, membership 100 Chopin Plaza have registration questions, please -

Discussion Guide

DISCUSSION GUIDE Does a free society require a free press? DEMOCRACY ON DEADLINE shadows courageous journalists and champions of independent media as they work to make, and keep, their societies free—in Afghanistan, Israel, Mexico, Nigeria, Russia, Sierra Leone and the United States. A FILM BY CALVIN SKAGGS DEMOCRACY ON DEADLINE FROM THE FILMMAKERS Hardly a day passes without another dire prediction about the disap- Vaclav Havel summarized a great deal about these ideals when he pearance of newspapers. Not to worry, we're told. The Internet will remarked that Americans conceive democracy as a horizon we substitute for newspapers. It belongs to everyone, and information always approach though never reach. The fuel that energizes us can flow freely there. But first, without our vigilance, the Internet may to trudge continually toward that horizon is the fresh information not remain free, and much of what passes for information there provided us by journalists who know enough to ask tough, relevant should be called opinion. Second, a vital press that provides accu- questions and dare enough to follow through until they get the rate, objective information is not free. Gathering, organizing, and dis- answers. Such journalists also refuse to accept the tired language, seminating such information costs a lot of money. Maintaining for- the "received wisdom," of the moment, whether that "wisdom" is eign bureaus from which reporters can deliver on-the-ground facts, delivered by the White House or talk radio, left-wing op-ed writers for example, has become a luxury enjoyed by only a few newspapers or right-wing cable network pundits. -

Celebrating Years

Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy celebrating 20 years 1986–2006 20th Anniversary 1986–2006 1 From the Director The Shorenstein Center happily celebrates twenty years of teaching, research and engage- ment with the broad topic of press, politics and public policy. This publication describes the history of the Shorenstein Center and its programs, both past and present. Our mission is to explore and illuminate the intersection of press, politics and public policy both in theory and in practice. Our political climate has changed dramatically in the wake of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001; issues of civil liberty and national security have dominated our political discourse ever since. Globalization, rising tensions between corporate objectives and journalistic ones, and myriad developments in technology are among an ever-evolving set of challenges confronting the news media. These matters present us with a daunting but perhaps never more important task. We thank all of the students, scholars, reporters, donors, conference participants, brown bag lunch speakers, visiting fellows and faculty, and our wonderful staff, all of whom have made this a vibrant, thoughtful and collegial community. We are grateful to everyone who has participated in the Center over the past twenty years and look forward to expanding our programs in new directions as we take on the challenges of the future. Alex S. Jones 2 Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy The History of the Shorenstein Center The Beginning The Shorenstein Center was founded in 1986, but its roots can be traced back to the early days of the John F. -

Atf-Report-Webfinal

KYE R. LEE/DALLAS MORNING NEWS MORNING LEE/DALLAS R. KYE The Bureau and the Bureau A Review of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives and a Proposal to Merge It with the Federal Bureau of Investigation Chelsea Parsons and Arkadi Gerney, with special advisor Mark D. Jones and fiscal impact analysis by Elaine Kamarck Spring 2015 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Page blank for print formatting. The Bureau and the Bureau A Review of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives and a Proposal to Merge It with the Federal Bureau of Investigation Chelsea Parsons and Arkadi Gerney, with special advisor Mark D. Jones and fiscal impact analysis by Elaine Kamarck Spring 2015 Page blank for print formatting. Contents 1 Introduction and executive summary 15 History of ATF 31 Interstate gun trafficking 57 Special venues for illegal sales: Gun shows and the Internet 73 Targeting violent gun offenders: ‘A small dog going after a big bone’ 97 ATF and gun industry regulation 117 Explosives, arson, and emergency response 131 Recommendations and conclusion 147 Appendix: Estimated cost savings resulting from the merger of ATF into the FBI By Elaine Kamarck 163 Endnotes Page blank for print formatting. Chapter 1 Introduction and executive summary Page blank for print formatting. 2 Center for American Progress | The Bureau and the Bureau Introduction and executive summary The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, or ATF, is an accident of history. The origins of the modern ATF date back to the Civil War era, when Congress created the Office of Internal Revenue within the Department of the Treasury to collect taxes on spirits and tobacco products. -

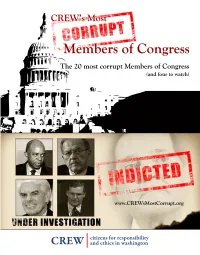

Crewserver05\Data\Research & Investigations

TABLE OF CONTENTS ______________________________________________________________________________ Executive Summary.........................................................................................................................1 Methodology....................................................................................................................................2 The Violators A. Members of the House.............................................................................................3 I. Vern Buchanan (R-FL) ...............................................................................4 II. Ken Calvert (R-CA).....................................................................................9 III. John Doolittle (R-CA)...............................................................................19 IV. Tom Feeney (R-FL)...................................................................................37 V. Vito Fossella (R-NY).................................................................................47 VI. William Jefferson (D-LA)..........................................................................50 VII. Jerry Lewis (R-CA)...................................................................................62 VIII. Dan Lipinski (D-IL)...................................................................................81 IX. Gary Miller (R-CA)...................................................................................86 X. Alan Mollohan (D-WV).............................................................................96