Sierra On-Line and the Origins of the Graphical Adventure Game • Laine Nooney

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

III. Here Be Dragons: the (Pre)History of the Adventure Game

III. Here Be Dragons: the (pre)history of the adventure game The past is like a broken mirror, as you piece it together you cut yourself. Your image keeps shifting and you change with it. MAX PAYNE 2: THE FALL OF MAX PAYNE At the end of the Middle Ages, Europe’s thousand year sleep – or perhaps thousand year germination – between antiquity and the Renaissance, wondrous things were happening. High culture, long dormant, began to stir again. The spirit of adventure grew once more in the human breast. Great cathedrals rose, the spirit captured in stone, embodiments of the human quest for understanding. But there were other cathedrals, cathedrals of the mind, that also embodied that quest for the unknown. They were maps, like the fantastic, and often fanciful, Mappa Mundi – the map of everything, of the known world, whose edges both beckoned us towards the unknown, and cautioned us with their marginalia – “Here be dragons.” (Bradbury & Seymour, 1997, p. 1357)1 At the start of the twenty-first century, the exploration of our own planet has been more or less completed2. When we want to experience the thrill, enchantment and dangers of past voyages of discovery we now have to rely on books, films and theme parks. Or we play a game on our computer, preferably an adventure game, as the experience these games create is very close to what the original adventurers must have felt. In games of this genre, especially the older type adventure games, the gamer also enters an unknown labyrinthine space which she has to map step by step, unaware of the dragons that might be lurking in its dark recesses. -

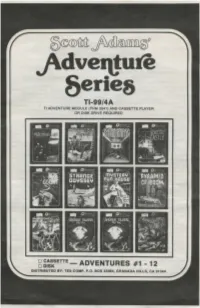

Tiadventureland-Manual

Texas Instruments Home Computer ADVENTURE Overview Author: Adventure International Language: TI BASIC Hardware: TI Home Computer TI Disk Drive Controller and Disk Memory Drive or cassette tape recorder Adventure Solid State Software™ Command Module Media: Diskette and Cassette Have you ever wanted to discover the treasures hidden in an ancient pyramid, encounter ghosts in an Old West ghost town, or visit an ancient civilization on the edge of the galaxy? Developed for Texas Instruments Incorporated by Adventure International, the Adventure game series lets you e xperience these and many other adventures in the comfort of your own home. To play any of the Adventure games, you need both the Adventure Command Module (sold separately) and a cassette- or diskette based Adventure game. The module contains the general program instructions which are customized by the particular cassette tape or diskette game you use with it. Each game in the series is designed to challenge your powers of logical reasoning and may take hours, days, or even weeks to complete. However, you can leave a game and continue it at another time by saving your current adventure on a cassette tape or diskette. Copyright© 1981, Texas Instruments Incorporated. Program and database contents copyright © 1981, Adventure International and Texas Instruments Incorporated. Page l Texas Instruments ADVENTURE Description ADVENTURE Description A variety of adventure games are available on cassette tape or Pyramid of Doom diskette from your local dealer or Adventure International. To give you an idea of the exciting and interesting games you can The Pyramid of Doom adventure starts in a desert near a pool of play, a brief summary of the currently available adventures is liquid, with a pole sticking out of the sand. -

It's Meant to Be Played

Issue 10 $3.99 (where sold) THE WAY It’s meant to be played Ultimate PC Gaming with GeForce All the best holiday games with the power of NVIDIA Far Cry’s creators outclass its already jaw-dropping technology Battlefi eld 2142 with an epic new sci-fi battle World of Warcraft: Company of Heroes Warhammer: The Burning Crusade Mark of Chaos THE NEWS Notebooks are set to transform Welcome... PC gaming Welcome to the 10th issue of The Way It’s Meant To Be Played, the he latest must-have gaming system is… T magazine dedicated to the very best in a notebook PC. Until recently considered mainly PC gaming. In this issue, we showcase a means for working on the move or for portable 30 games, all participants in NVIDIA’s presentations, laptops complete with dedicated graphic The Way It’s Meant To Be Played processing units (GPUs) such as the NVIDIA® GeForce® program. In this program, NVIDIA’s Go 7 series are making a real impact in the gaming world. Latest thing: Laptops developer technology engineers work complete with dedicated The advantages are obvious – gamers need no longer be graphic processing units with development teams to get the are making an impact in very best graphics and effects into tied to their desktop set-up. the gaming world. their new titles. The games are then The new NVIDIA® GeForce® Go 7900 notebook rigorously tested by three different labs GPUs are designed for extreme HD gaming, and gaming at NVIDIA for compatibility, stability, and hardware specialists such as Alienware and Asus have performance to ensure that any game seen the potential of the portable platform. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Engineering emergence: applied theory for game design Dormans, J. Publication date 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Dormans, J. (2012). Engineering emergence: applied theory for game design. Creative Commons. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Ludography Agricola (2007, board game). Lookout Games, Uwe Rosenberg. Americas Army (2002, PC). U.S. Army. Angry Birds (2009, iOS, Android, others). Rovio Mobile Ltd. Ascent (2009, PC). J. Dormans. Assassins Creed (2007, PS3, Xbox 360). Ubisoft, Inc., Ubisoft Divertissements Inc. Baldurs Gate (1998, PC). Interplay Productions, Inc. BioWare Corporations. Bejeweled (2000, PC). PopCap Games, Inc. Bewbees (2011, Android, iOS). GewGawGames. Blood Bowl, third edition (1994, board game). -

Here Is Tt,E a Glow-Globe in Here, Too, but It Is the Only Source of Light

Edi+or" " , Bob Albrec.ht BooI<. Reviews"" Art, , , , , , Jane wood Denl"lis AlliSOn . C3i /I Holden Pr-oclv<:.ti on, ,r-b.m Scarvi e Li II io.n Quirke Bob ,v'Iullen Do.vld Ka.ufrYIG\Yl Dave De lisle Alber.,. Bradley' f'Ib.ry Jo Albrecht c 0000000 o ~ 0 o 0 • 0 o 0 o 0 Q~ PCC is publisnee\ 5 +imes • Grovp. svb5C.r,'phOn~(al/ 000 (ana sometimes more) dvrinq rl'lQilec +0 ~me add~ss): g -the 5c.hool tear. SubscriptionS 2-~ $4 00 eo.cJ, ! ~ be9in with 't-he fi~t 'Issve in 10-"" $ 3..so ea.c.h ~ o The .fall. /00 or-more $3°Oeach (; Q 0 tJ • Get bG\c.k issues while °8 o If you are an elementqt"Y 0 They IG\st ~+ the toIJowi""j Q or seconc:Ja.rY 9Chool stvcJ6,t low low pnc.es; e • you can00 subScribe to pee. vol I Nos 1-5 12 co 2 C!) for $3 , Send ~h,. check, or p 'U (/) rnoney order, No ~~G\se. orders, Vol Ir fVoI<:> I~!S qoo . e Use your $0,+)£ /ADDRESS' PlEQse eNO b - 5p!!cio.l arl',SSle (() o seno vs some eVidence tha1- you Or ml)( up InclividuQI Issues: () (I are G\ stu~",+, z.-~ 80 ~ ea.ch Cl) o 10-""'} '"70 t ectc. h 0 , Sit"lCJle. svb5c.ription\,. are. • /00 +' bO ea.cJ., . ! e $5 .far' 5 'ISSueS, (~ out- W lei \'k +0 '" o Side VSA-)urface MOIil,' ov .;t0v I e weG\r our Q A .. I cover, [)n,.qon shirts a.-e A ~ "'12 -air mai n(MJ G\vailable at $3$0 eod, '" 0 (Calif, res; dt'nts (Add While 0 sale~ ~')t, g with green prj "ti "va ' S.l'I D ""eo D LG LJ 0 ~OOo@c00000QctcD00(!) 00000000<0 0 0e~ooo OO(l)OOOO~OOO SEND cHECk' OR MONel ORDER 'R>: ~~~ Po 60)( 310 • MENLO PARI<. -

J\Dveqtute Series Tl-99/4A TI ADVENTURE MODULE (PHM 3041) and CASSETIE PLAYER OR DISK DRIVE REQUIRED SCOTT ADAMS' ADVENTURE by Scott Adams INSTRUCTIONS TEX•COMP- P.O

®~@lilt ftcdl®mID~0 j\dveqtute Series Tl-99/4A TI ADVENTURE MODULE (PHM 3041) AND CASSETIE PLAYER OR DISK DRIVE REQUIRED SCOTT ADAMS' ADVENTURE by Scott Adams INSTRUCTIONS TEX•COMP- P.o. Box 33089 • Granada Hills, CA 91344 (818) 366-6631 ADVENTURE Overview CopyrightC1981 by Adventure International, Texas Instruments, Inc. Cl 985 TEX-COMP TI Users Supply Company All rights reserved Printed with permission ADVENTURES by Scott Adams Author: Adventure International AN OVERVIEW How do you know which objects you need? Trial and er Language: TI Basic I stood at the bottom of a deep chasm. Cool air sliding ror, logic and imagination. Each time you try some action, down the sides of the crevasse hit waves of heat rising you learn a little more about the game. Hardware: TI Home Computer from a stream of bubbling lava and formed a mist over the Which brings us to the term "game" again. While called sluggish flow. Through the swrlling clouds I caught games, Adventures are actually puzzles because you have to TI Disk Drive Controller and Disk Memory Drive or glimpses of two ledges high above me: one was bricked, discover which way the pieces (actions, manipulations, use cassette tape recorder the other appeared to lead to the throne room I had been of magic words, etc.) lit together in order to gather your seeking. treasures or accomplish the mission. Like a puzzle, there are Adventure Solld State Software™ Command Module A blast of fresh air cleared the mist near my feet and a number of ways to fit the pieces together; players who like a single gravestone a broken sign appeared momen have found and stored ail the treasures (there are 13) of Ad Media: Diskette and Cassette tarily. -

Download Twisty Little Passages: an Approach to Interactive Fiction

TWISTY LITTLE PASSAGES: AN APPROACH TO INTERACTIVE FICTION DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Nick Montfort | 302 pages | 01 Apr 2005 | MIT Press Ltd | 9780262633185 | English | Cambridge, Mass., United States Slashdot Top Deals I got about a quarter of the way into this and had to stop. In Montfort's words, Infocomwhich was founded June 22, by Lebling, Blank, Anderson, and seven other MIT alumni, "began work on the foundation of IF while the plot of ground that it was to be built upon had not been completely surveyed. Slashdot Apparel is back! Genre fiction is a type of literature, and trying to actually seperate one from the other is a fool's errand. I think what you may be getting at is the fact that writing a compelling IF world is literally NP hard. Hitchhiker's Guide project, which began in February and was slated ambitiously to be completed by the following Christmas. Friend Reviews. Instead, what this book really is is a very comprehensive history of the form. There's really not that much meat there; Montfort goes into a detailed history and categorization of riddles that isn't all that relevant to IF. Played them, loved them, but goddam that transparent crystal 3D mze was a killer. Nick Montfort. Montfort then discusses Adventure Twisty Little Passages: An Approach to Interactive Fiction its precursors including the I Ching and Dungeons and Dragonsand follows this with an examination of mainframe text games developed in response, focusing on the most influential work of that era, Zork. The reviewer's memory of Monty Python's a little weak. -

Unix Programmer's Manual

There is no warranty of merchantability nor any warranty of fitness for a particu!ar purpose nor any other warranty, either expressed or imp!ied, a’s to the accuracy of the enclosed m~=:crials or a~ Io ~helr ,~.ui~::~::.j!it’/ for ~ny p~rficu~ar pur~.~o~e. ~".-~--, ....-.re: " n~ I T~ ~hone Laaorator es 8ssumg$ no rO, p::::nS,-,,.:~:y ~or their use by the recipient. Furln=,, [: ’ La:::.c:,:e?o:,os ~:’urnes no ob~ja~tjon ~o furnish 6ny a~o,~,,..n~e at ~ny k:nd v,,hetsoever, or to furnish any additional jnformstjcn or documenta’tjon. UNIX PROGRAMMER’S MANUAL F~ifth ~ K. Thompson D. M. Ritchie June, 1974 Copyright:.©d972, 1973, 1974 Bell Telephone:Laboratories, Incorporated Copyright © 1972, 1973, 1974 Bell Telephone Laboratories, Incorporated This manual was set by a Graphic Systems photo- typesetter driven by the troff formatting program operating under the UNIX system. The text of the manual was prepared using the ed text editor. PREFACE to the Fifth Edition . The number of UNIX installations is now above 50, and many more are expected. None of these has exactly the same complement of hardware or software. Therefore, at any particular installa- tion, it is quite possible that this manual will give inappropriate information. The authors are grateful to L. L. Cherry, L. A. Dimino, R. C. Haight, S. C. Johnson, B. W. Ker- nighan, M. E. Lesk, and E. N. Pinson for their contributions to the system software, and to L. E. McMahon for software and for his contributions to this manual. -

Christy Marx

Write Your Way Into Animation and Games Write Your Way Into Animation and Games Create a Writing Career in Animation and Games Christy Marx AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK © 2010 Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, elec- tronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, fur- ther information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organiza- tions such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treat- ment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluat- ing and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. -

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Test List Report OHS encourages teachers to implement independent reading to suit their curriculum. Accelerated Reader quizzes/books include a wide range of reading levels and subject matter. Some books may contain mature subject matter and/or strong language. If a student finds a book objectionable/uncomfortable he or she should choose another book. Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 68630EN 10th Grade Joseph Weisberg 5.7 11.0 101453EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Maureen Johnson 5.0 9.0 136675EN 13 Treasures Michelle Harrison 5.3 11.0 39863EN 145th Street: Short Stories Walter Dean Myers 5.1 6.0 135667EN 16 1/2 On the Block Babygirl Daniels 5.3 4.0 135668EN 16 Going on 21 Darrien Lee 4.8 6.0 53617EN 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 86429EN 1634: The Galileo Affair Eric Flint 6.5 31.0 11101EN A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald 7.7 1.0 104010EN 1776 David G. McCulloug 9.1 20.0 80002EN 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems o Naomi Shihab Nye 5.8 2.0 53175EN 1900-20: A Shrinking World Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 53176EN 1920-40: Atoms to Automation Steve Parker 7.9 1.0 53177EN 1940-60: The Nuclear Age Steve Parker 7.7 1.0 53178EN 1960s: Space and Time Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 130068EN 1968 Michael T. Kaufman 9.9 7.0 53179EN 1970-90: Computers and Chips Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 36099EN The 1970s from Watergate to Disc Stephen Feinstein 8.2 1.0 36098EN The 1980s from Ronald Reagan to Stephen Feinstein 7.8 1.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 53180EN 1990-2000: The Electronic Age Steve Parker 8.0 1.0 72374EN 1st to Die James Patterson 4.5 12.0 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Ad Jules Verne 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. -

The Last Two Decades Have Witnessed the Growth of Video and Computer Gaming from a Small Hobbyist Pastime to a Major Form of Entertainment

Chris Lynskey STS 145 Case History Leisure Suit Larry The last two decades have witnessed the growth of video and computer gaming from a small hobbyist pastime to a major form of entertainment. During its integration into modern culture, gaming has necessarily adopted certain traits that are inherent in human existence, namely violence and sex. Violence has actually been an integral part of games from the very beginning, whether it was the destruction of enemy tanks or missions against invading aliens. The integration of sex into gaming though, has taken a considerably different course. Although there were several small niches of games devoted to that topic in the early 1980s, it wasn’t until the late 1980s and early 1990s that sex began to gain acceptance as a part of mainstream gaming. Perhaps the most significant catalyst to that process was the highly popular Leisure Suit Larry series produced by Sierra and developed in large by Al Lowe. The history of Leisure Suit Larry begins with that of its publishing company, Sierra On-Line. It was incorporated in 1979 by Ken and Roberta Williams in a small town near Yosemite. They decided to direct their focus to a then unexplored genre, adventure games. Although their first big success was the King’s Quest series, in the company’s early days they received national attention due to a small game written by Chuck Benton. This game was certainly a unique element of Sierra’s catalog at the time: it was the company’s only non-graphic work and their sole adult-oriented game. -

Sierra-88Catalog3

.SIERRA: "A miracle from the kitchen. " Mystery House, eventually sold over 10,000 copies. It was a hundred times more successful oday, I don 't work out of the spare ierra didn't start in a bedroom anymore (our first house garage like other software burned down in late 1982). 1 had to vendors. We weren 't born begin designing my adventures at the officeT in downtown Coarsegold. We hired some out of a marketing plan or staffed and funded by a major extra hands to help us out (about 77 pair at last corporation. My husband and I count) and now our little software company takes started Sierra on a rickety table, in up most of the town 's biggest office building. It 's the kitchen of our small family home. very different from working at home, but the office Our first software product began as an still has a very "homey" feel to it. We're all very evening project. Ken (my husband) and I Mystery House, casual (no neckties or shoes) and everyone gets our first adventure game, along. It sounds a little trite, but we really do try to worked on it together. It was kind of like when from 1980. we hung the pictures in the den or assembled the be one happy family. Every time 1 visit the Sierra family photo albums - I supplied the creative than we ever thought it would be! From that Before we knew it, we had occupied three otber offices, I think of a little line my mom used to say when she brought dinner to the table, ''Here comes design and Ken did the technical work.