A Genetic Screen Implicates a CWC16/Yju2/CCDC130 Protein and SMU1 in Alternative Splicing in Arabidopsis Thaliana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

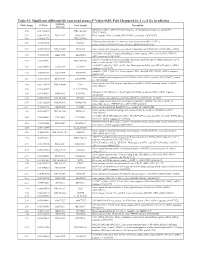

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds. -

A High-Resolution 3D Epigenomic Map Reveals Insights Into the Creation of the Prostate Cancer Transcriptome

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12079-8 OPEN A high-resolution 3D epigenomic map reveals insights into the creation of the prostate cancer transcriptome Suhn Kyong Rhie 1, Andrew A. Perez1, Fides D. Lay1, Shannon Schreiner 1, Jiani Shi1, Jenevieve Polin 1 & Peggy J. Farnham 1 1234567890():,; To better understand the impact of chromatin structure on regulation of the prostate cancer transcriptome, we develop high-resolution chromatin interaction maps in normal and pros- tate cancer cells using in situ Hi-C. By combining the in situ Hi-C data with active and repressive histone marks, CTCF binding sites, nucleosome-depleted regions, and tran- scriptome profiling, we identify topologically associating domains (TADs) that change in size and epigenetic states between normal and prostate cancer cells. Moreover, we identify normal and prostate cancer-specific enhancer-promoter loops and involved transcription factors. For example, we show that FOXA1 is enriched in prostate cancer-specific enhancer- promoter loop anchors. We also find that the chromatin structure surrounding the androgen receptor (AR) locus is altered in the prostate cancer cells with many cancer-specific enhancer-promoter loops. This creation of 3D epigenomic maps enables a better under- standing of prostate cancer biology and mechanisms of gene regulation. 1 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine and the Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089, USA. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to S.K.R. (email: [email protected]) or to P.J.F. (email: [email protected]) NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | (2019) 10:4154 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12079-8 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 ARTICLE NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12079-8 rostate cancer is the leading cause of new cancer cases and Results Pthe second most common cancer in men and the fourth Cancer-specific TADs that lead to transcriptome changes. -

Strand Breaks for P53 Exon 6 and 8 Among Different Time Course of Folate Depletion Or Repletion in the Rectosigmoid Mucosa

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURE COLON p53 EXONIC STRAND BREAKS DURING FOLATE DEPLETION-REPLETION INTERVENTION Supplemental Figure Legend Strand breaks for p53 exon 6 and 8 among different time course of folate depletion or repletion in the rectosigmoid mucosa. The input of DNA was controlled by GAPDH. The data is shown as ΔCt after normalized to GAPDH. The higher ΔCt the more strand breaks. The P value is shown in the figure. SUPPLEMENT S1 Genes that were significantly UPREGULATED after folate intervention (by unadjusted paired t-test), list is sorted by P value Gene Symbol Nucleotide P VALUE Description OLFM4 NM_006418 0.0000 Homo sapiens differentially expressed in hematopoietic lineages (GW112) mRNA. FMR1NB NM_152578 0.0000 Homo sapiens hypothetical protein FLJ25736 (FLJ25736) mRNA. IFI6 NM_002038 0.0001 Homo sapiens interferon alpha-inducible protein (clone IFI-6-16) (G1P3) transcript variant 1 mRNA. Homo sapiens UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-D-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 15 GALNTL5 NM_145292 0.0001 (GALNT15) mRNA. STIM2 NM_020860 0.0001 Homo sapiens stromal interaction molecule 2 (STIM2) mRNA. ZNF645 NM_152577 0.0002 Homo sapiens hypothetical protein FLJ25735 (FLJ25735) mRNA. ATP12A NM_001676 0.0002 Homo sapiens ATPase H+/K+ transporting nongastric alpha polypeptide (ATP12A) mRNA. U1SNRNPBP NM_007020 0.0003 Homo sapiens U1-snRNP binding protein homolog (U1SNRNPBP) transcript variant 1 mRNA. RNF125 NM_017831 0.0004 Homo sapiens ring finger protein 125 (RNF125) mRNA. FMNL1 NM_005892 0.0004 Homo sapiens formin-like (FMNL) mRNA. ISG15 NM_005101 0.0005 Homo sapiens interferon alpha-inducible protein (clone IFI-15K) (G1P2) mRNA. SLC6A14 NM_007231 0.0005 Homo sapiens solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter) member 14 (SLC6A14) mRNA. -

RNA Splicing in the Transition from B Cells

RNA Splicing in the Transition from B Cells to Antibody-Secreting Cells: The Influences of ELL2, Small Nuclear RNA, and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress This information is current as of September 24, 2021. Ashley M. Nelson, Nolan T. Carew, Sage M. Smith and Christine Milcarek J Immunol 2018; 201:3073-3083; Prepublished online 8 October 2018; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800557 Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/content/201/10/3073 Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2018/10/05/jimmunol.180055 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Material 7.DCSupplemental References This article cites 44 articles, 16 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/201/10/3073.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision by guest on September 24, 2021 • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2018 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology RNA Splicing in the Transition from B Cells to Antibody-Secreting Cells: The Influences of ELL2, Small Nuclear RNA, and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Ashley M. -

CD4+ T Cells from Children with Active Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Show

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN CD4+ T cells from children with active juvenile idiopathic arthritis show altered chromatin features associated with transcriptional abnormalities Evan Tarbell1,3,5,7, Kaiyu Jiang2,7, Teresa R. Hennon2, Lucy Holmes2, Sonja Williams2, Yao Fu4, Patrick M. Gafney4, Tao Liu1,3,6 & James N. Jarvis2,3* Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is one of the most common chronic diseases in children. While clinical outcomes for patients with juvenile JIA have improved, the underlying biology of the disease and mechanisms underlying therapeutic response/non-response are poorly understood. We have shown that active JIA is associated with distinct transcriptional abnormalities, and that the attainment of remission is associated with reorganization of transcriptional networks. In this study, we used a multi- omics approach to identify mechanisms driving the transcriptional abnormalities in peripheral blood CD4+ T cells of children with active JIA. We demonstrate that active JIA is associated with alterations in CD4+ T cell chromatin, as assessed by ATACseq studies. However, 3D chromatin architecture, assessed by HiChIP and simultaneous mapping of CTCF anchors of chromatin loops, reveals that normal 3D chromatin architecture is largely preserved. Overlapping CTCF binding, ATACseq, and RNAseq data with known JIA genetic risk loci demonstrated the presence of genetic infuences on the observed transcriptional abnormalities and identifed candidate target genes. These studies demonstrate the utility of multi-omics approaches for unraveling important questions regarding the pathobiology of autoimmune diseases. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a broad term that describes a clinically heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by chronic synovial hypertrophy and infammation, with onset before 16 years of age 1. -

(B6;129.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sor Tm20(CAG-Ctgf-GFP)Jsd) Were Crossed with Female Foxd1cre/+ Heterozygote Mice 1, and Experimental Mice Were Selected As Foxd1cre/+; Rs26cig/+

Supplemental Information SI Methods Animal studies Heterozygote mice (B6;129.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sor tm20(CAG-Ctgf-GFP)Jsd) were crossed with female Foxd1Cre/+ heterozygote mice 1, and experimental mice were selected as Foxd1Cre/+; Rs26CIG/+. In some studies Coll-GFPTg or TCF/Lef:H2B-GFPTg mice or Foxd1Cre/+; Rs26tdTomatoR/+ mice were used as described 2; 3. Left kidneys were subjected to ureteral obstruction using a posterior surgical approach as described 2. In some experiments recombinant mouse DKK1 (0.5mg/kg) or an equal volume of vehicle was administered by daily IP injection. In the in vivo ASO experiment, either specific Lrp6 (TACCTCAATGCGATTT) or scrambled negative control ASO (AACACGTCTATACGC) (30mg/kg) (Exiqon, LNA gapmers) was administered by IP injection on d-1, d1, d4, and d7. In other experiments anti-CTGF domain-IV antibodies (5mg/kg) or control IgG were administered d-1, d1 and d6. All animal experiments were performed under approved IACUC protocols held at the University of Washington and Biogen. Recombinant protein and antibody generation and characterization Human CTGF domain I (sequence Met1 CPDEPAPRCPAGVSLVLDGCGCCRVCAKQLGELCTERDPCDPHKGLFC), domain I+II (sequence Met1CPDEPAPRCPAGVSLVLDGCGCCRVCAKQLGELCTERDPCDPHKGLFCCIFGGT VYRSGESFQSSCKYQCTCLDGAVGCMPLCSMDVRLPSPDCPFPRRVKLPGKCCEE) were cloned and expressed in 293 cells, and purified by Chelating SFF(Ni) Column, tested for single band by SEC and PAGE, and tested for absence of contamination. Domain-IV (sequence GKKCIRTPKISKPIKFELSGCTSMKTYRAKFCGVCTDGRCCTPHRTTTLPVEFKCPDGE VMKKNMMFIKTCACHYNCPGDNDIFESLYYRKMY) was purchased from Peprotech. Mouse or human DKK1 was generated from the coding sequence with some modifications and a tag. Secreted protein was harvested from 293 cells, and purified by nickel column, and tested for activity in a supertopflash (STF) assay 4. DKK1 showed EC50 of 0.69nM for WNT3a-induced WNT signaling in STF cells. -

Supplementary Data

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION A study restricted to chemokine receptors as well as a genome-wide transcript analysis uncovered CXCR4 as preferentially expressed in Ewing's sarcoma (Ewing's sarcoma) cells of metastatic origin (Figure 4). Transcriptome analyses showed that in addition to CXCR4, genes known to support cell motility and invasion topped the list of genes preferentially expressed in metastasis-derived cells (Figure 4D). These included kynurenine 3-monooxygenase (KMO), galectin-1 (LGALS1), gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP), procollagen C-endopeptidase enhancer (PCOLCE), and ephrin receptor B (EPHB3). KMO, a key enzyme of tryptophan catabolism, has not been linked to metastasis. Tryptophan and its catabolites, however, are involved in immune evasion by tumors, a process that can assist in tumor progression and metastasis (1). LGALS1, GRP, PCOLCE and EPHB3 have been linked to tumor progression and metastasis of several cancers (2-4). Top genes preferentially expressed in L-EDCL included genes that suppress cell motility and/or potentiate cell adhesion such as plakophilin 1 (PKP1), neuropeptide Y (NPY), or the metastasis suppressor TXNIP (5-7) (Figure 4D). Overall, L-EDCL were enriched in gene sets geared at optimizing nutrient transport and usage (Figure 4D; Supplementary Table 3), a state that may support the early stages of tumor growth. Once tumor growth outpaces nutrient and oxygen supplies, gene expression programs are usually switched to hypoxic response and neoangiogenesis, which ultimately lead to tumor egress and metastasis. Accordingly, gene sets involved in extracellular matrix remodeling, MAPK signaling, and response to hypoxia were up-regulated in M-EDCL (Figure 4D; Supplementary Table 4), consistent with their association to metastasis in other cancers (8, 9). -

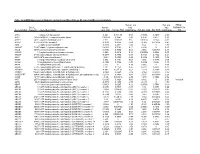

Mrna Expression in Human Leiomyoma and Eker Rats As Measured by Microarray Analysis

Table 3S: mRNA Expression in Human Leiomyoma and Eker Rats as Measured by Microarray Analysis Human_avg Rat_avg_ PENG_ Entrez. Human_ log2_ log2_ RAPAMYCIN Gene.Symbol Gene.ID Gene Description avg_tstat Human_FDR foldChange Rat_avg_tstat Rat_FDR foldChange _DN A1BG 1 alpha-1-B glycoprotein 4.982 9.52E-05 0.68 -0.8346 0.4639 -0.38 A1CF 29974 APOBEC1 complementation factor -0.08024 0.9541 -0.02 0.9141 0.421 0.10 A2BP1 54715 ataxin 2-binding protein 1 2.811 0.01093 0.65 0.07114 0.954 -0.01 A2LD1 87769 AIG2-like domain 1 -0.3033 0.8056 -0.09 -3.365 0.005704 -0.42 A2M 2 alpha-2-macroglobulin -0.8113 0.4691 -0.03 6.02 0 1.75 A4GALT 53947 alpha 1,4-galactosyltransferase 0.4383 0.7128 0.11 6.304 0 2.30 AACS 65985 acetoacetyl-CoA synthetase 0.3595 0.7664 0.03 3.534 0.00388 0.38 AADAC 13 arylacetamide deacetylase (esterase) 0.569 0.6216 0.16 0.005588 0.9968 0.00 AADAT 51166 aminoadipate aminotransferase -0.9577 0.3876 -0.11 0.8123 0.4752 0.24 AAK1 22848 AP2 associated kinase 1 -1.261 0.2505 -0.25 0.8232 0.4689 0.12 AAMP 14 angio-associated, migratory cell protein 0.873 0.4351 0.07 1.656 0.1476 0.06 AANAT 15 arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase -0.3998 0.7394 -0.08 0.8486 0.456 0.18 AARS 16 alanyl-tRNA synthetase 5.517 0 0.34 8.616 0 0.69 AARS2 57505 alanyl-tRNA synthetase 2, mitochondrial (putative) 1.701 0.1158 0.35 0.5011 0.6622 0.07 AARSD1 80755 alanyl-tRNA synthetase domain containing 1 4.403 9.52E-05 0.52 1.279 0.2609 0.13 AASDH 132949 aminoadipate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase -0.8921 0.4247 -0.12 -2.564 0.02993 -0.32 AASDHPPT 60496 aminoadipate-semialdehyde -

A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of High-LET Ionizing Radiations in Human Gene Expression

Supplementary Materials A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of High-LET Ionizing Radiations in Human Gene Expression Table S1. Statistically significant DEGs (Adj. p-value < 0.01) derived from meta-analysis for samples irradiated with high doses of HZE particles, collected 6-24 h post-IR not common with any other meta- analysis group. This meta-analysis group consists of 3 DEG lists obtained from DGEA, using a total of 11 control and 11 irradiated samples [Data Series: E-MTAB-5761 and E-MTAB-5754]. Ensembl ID Gene Symbol Gene Description Up-Regulated Genes ↑ (2425) ENSG00000000938 FGR FGR proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase ENSG00000001036 FUCA2 alpha-L-fucosidase 2 ENSG00000001084 GCLC glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit ENSG00000001631 KRIT1 KRIT1 ankyrin repeat containing ENSG00000002079 MYH16 myosin heavy chain 16 pseudogene ENSG00000002587 HS3ST1 heparan sulfate-glucosamine 3-sulfotransferase 1 ENSG00000003056 M6PR mannose-6-phosphate receptor, cation dependent ENSG00000004059 ARF5 ADP ribosylation factor 5 ENSG00000004777 ARHGAP33 Rho GTPase activating protein 33 ENSG00000004799 PDK4 pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 ENSG00000004848 ARX aristaless related homeobox ENSG00000005022 SLC25A5 solute carrier family 25 member 5 ENSG00000005108 THSD7A thrombospondin type 1 domain containing 7A ENSG00000005194 CIAPIN1 cytokine induced apoptosis inhibitor 1 ENSG00000005381 MPO myeloperoxidase ENSG00000005486 RHBDD2 rhomboid domain containing 2 ENSG00000005884 ITGA3 integrin subunit alpha 3 ENSG00000006016 CRLF1 cytokine receptor like -

A Common Genetic Architecture Enables the Lossy Compression of Large CRISPR Libraries

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.18.423506; this version posted December 18, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. A common genetic architecture enables the lossy compression of large CRISPR libraries Boyang Zhao1,*, Yiyun Rao2, Luke Gilbert3-5, Justin Pritchard1,2,* 1. Department of Biomedical Engineering, Pennsylvania State University 2. Huck Institute for the Life Sciences, Pennsylvania State University 3. Department of Urology, University of California at San Francisco 4. Department of Cellular & Molecular Pharmacology, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA 5. Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA * Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to JP ([email protected]) and BZ ([email protected]) bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.18.423506; this version posted December 18, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract There are thousands of ubiquitously expressed mammalian genes, yet a genetic knockout can be lethal to one cell, and harmless to another. This context specificity confounds our understanding of genetics and cell biology. 2 large collections of pooled CRISPR screens offer an exciting opportunity to explore cell specificity.