Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isabel Clara Eugenia and Peter Paul Rubens’S the Triumph of the Eucharist Tapestry Series

ABSTRACT Title of Document: PIETY, POLITICS, AND PATRONAGE: ISABEL CLARA EUGENIA AND PETER PAUL RUBENS’S THE TRIUMPH OF THE EUCHARIST TAPESTRY SERIES Alexandra Billington Libby, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Directed By: Professor Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., Department of Art History and Archeology This dissertation explores the circumstances that inspired the Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia, Princess of Spain, Archduchess of Austria, and Governess General of the Southern Netherlands to commission Peter Paul Rubens’s The Triumph of the Eucharist tapestry series for the Madrid convent of the Descalzas Reales. It traces the commission of the twenty large-scale tapestries that comprise the series to the aftermath of an important victory of the Infanta’s army over the Dutch in the town of Breda. Relying on contemporary literature, studies of the Infanta’s upbringing, and the tapestries themselves, it argues that the cycle was likely conceived as an ex-voto, or gift of thanks to God for the military triumph. In my discussion, I highlight previously unrecognized temporal and thematic connections between Isabel’s many other gestures of thanks in the wake of the victory and The Triumph of the Eucharist series. I further show how Rubens invested the tapestries with imagery and a conceptual conceit that celebrated the Eucharist in ways that symbolically evoked the triumph at Breda. My study also explores the motivations behind Isabel’s decision to give the series to the Descalzas Reales. It discusses how as an ex-voto, the tapestries implicitly credited her for the triumph and, thereby, affirmed her terrestrial authority. Drawing on the history of the convent and its use by the king of Spain as both a religious and political dynastic center, it shows that the series was not only a gift to the convent, but also a gift to the king, a man with whom the Infanta had developed a tense relationship over the question of her political autonomy. -

A Constellation of Courts the Courts and Households of Habsburg Europe, 1555-1665

A Constellation of Courts The Courts and Households of Habsburg Europe, 1555-1665 A Constellation of Courts The Courts and Households of Habsburg Europe, 1555-1665 Edited by René Vermeir, Dries Raeymaekers, and José Eloy Hortal Muñoz © 2014 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium) All rights reserved. Except in those cases expressly determined by law, no part of this publication may be multiplied, saved in an automated datafile or made public in any way whatsoever without the express prior written consent of the publishers. ISBN 978 90 5867 990 1 e-ISBN 978 94 6166 132 6 D / 2014 / 1869 / 47 NUR: 685, 697 Cover illustration: Lucas I van Valckenborgh, “Frühlingslandschaft (Mai)”, (inv. Nr. GG 1065), Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna Contents Courts and households of the Habsburg dynasty: history and historiography José Eloy Hortal Muñoz, Dries Raeymaekers and René Vermeir 7 The political configuration of the Spanish Monarchy: the court and royal households José Martínez Millán 21 The court of Madrid and the courts of the viceroys Manuel Rivero 59 The economic foundations of the royal household of the Spanish Habsburgs, 1556–1621 Carlos Javier de Carlos Morales 77 The household of archduke Albert of Austria from his arrival in Madrid until his election as governor of the Low Countries: 1570–1595 José Eloy Hortal Muñoz 101 Flemish elites under Philip III’s patronage (1598-1621): household, court and territory in the Spanish Habsburg Monarchy* -

The Portrait of Juana of Austria in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum

IN THE KING’S NAME The Portrait of Juana of Austria in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum Leticia Ruiz Gómez This text is published under an international Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Creative Commons licence (BY-NC-ND), version 4.0. It may therefore be circulated, copied and reproduced (with no alteration to the contents), but for educational and research purposes only and always citing its author and provenance. It may not be used commercially. View the terms and conditions of this licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncnd/4.0/legalcode Using and copying images are prohibited unless expressly authorised by the owners of the photographs and/or copyright of the works. © of the texts: Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao Photography credits © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao: fig. 1 © Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien: fig. 7 © Musées Royaux des Beaux Arts de Belgique, Bruxelles: fig. 4 © Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid: figs. 2, 3, 5, 9 and 10 © Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid: figs. 6 and 8 Text published in: B’06 : Buletina = Boletín = Bulletin. Bilbao : Bilboko Arte Eder Museoa = Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao = Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, no. 2, 2007, pp. 85-123. Sponsored by: 2 n the 1550s Princess Juana of Portugal was a regular subject for portrait artists, being one of the leading women in the House of Austria, the dynasty that dominated the political scene in Europe throughout the I16th century. The youngest daughter of Charles V and Isabella of Portugal, she had a special role to play in her father’s geopolitical strategies, first as the wife of the heir to the Portuguese throne, to whom she bore a posthumous son who would eventually come to the throne of Spain’s neighbour, and subsequently as regent of the Emperor’s peninsular territories. -

I GLADLY STRAINED MY EYES to FOLLOW YOU — Entrance Hall — the Landing

a guided tour of Pollock House by Shauna McMullan I GLADLY STRAINED MY EYES TO FOLLOW YOU — Entrance Hall — The Landing UNKNOWN LADY UNKNOWN dates unknown dates unknown Karen Cornfield, House Manager, Pollok House Kate Davis, artist Is that a fly on her nose? Untitled It’s not meant to be there. Unasked There’s meant to be a story, Unspoken The person behind the face. Unkempt Unaccustomed This portrait of a woman was painted by a man. Unseen We know about him, not about her. Unsteady Unnecessary “He had a name and was born on a date. He came from a Unwilling country and was born in a place. He painted things that were Unemployed typical of the time. He went to a city and another country. His Unwise work is exhibited among the work of other men. His most Undressed famous work is a painting.” Ungovernable Unsound (But, not this one.) Unhealthy Unflappable When was she born and where did she live? Unlucky Where did she travel and what did she see? Unmarked Where can we see her life’s work? Unpretentious What was her passion? Unsightly What did she love? Unprincipled Unable Separated from her story, Unnatural Captured in a frame, Unwritten Hung upon a wall, Unbending To be remembered without a name. Unreasonable Unsettled Unstable — Silver Corridor Unaware Uncommunicative ANNE MARIE CHARLOTTE CORDAY Unwholesome Unsaid 1768 – 1793 Untapped Dr. Sarah Tripp, artist Unbecoming Unarmed Moods did not settle upon her face. When I arrived Untold (when I first saw her) this was the case – no mood. -

(Heaven) and Gaia (Earth), Was the Powerful Goddes

Water n Greek mythology MNEMOSYNE, daughter of the primordial Titan deities Uranus (Heaven) and Gaia (Earth), I was the powerful goddess of memory, the inventor of language and mother of the nine muses. Mnemosyne presided over the spring of memory in the underworld where souls had the choice to drink either from the River Lethe, forget their past life and be re-incarnated, or to drink from her own spring and spend eternity in the peace of the Elysian Fields. The words amnesia, amnesty, mnemonic, monument derive from her name. Jupiter, in the guise of a shepherd, approaches Mnemosyne, seated on the left at the edge of a wood by her spring. Illustration by LeClerc to Isaac de Benserade’s adaptation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses Paris, 1676. ©Trustees of the British Museum. Since ancient times water has been closely linked with memory. Many people believe that the memory of a blessing can be retained in water from holy shrines and can bring healing. In the Middle Ages the power of holy water was considered so great that pilgrims bought small flasks of it hoping that its blessing would accompany them as their journey continued. Some churches locked their fonts to prevent its theft. Homeopathic remedies defy conventional scientific Medieval pilgrim’s understanding by suggesting that water has the ability to lead alloy retain an electromagnetic memory of substances previously ampulla for carrying dissolved in it to the point that no single molecule of the holy water. original substance remains. The River Ise rises in the field at Naseby where the memory of the Civil War battle of 1645 is embedded in the Northamptonshire landscape. -

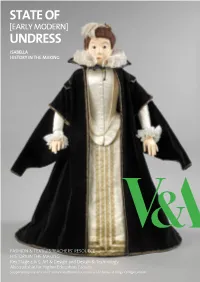

History in the Making – Isabella

ISABELLA HISTORY IN THE MAKING FASHION & TEXTILES TEACHERS’ RESOURCE HISTORY IN THE MAKING Key Stage 4 & 5: Art & Design and Design & Technology Also suitable for Higher Education Groups Supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council with thanks to Kings College London 1 FOREPART (PANEL) LIMEWOOD MANNEQUIN BODICE CHOPINES (SHOES) SLEEVE RUFFS GOWN NECK RUFF & REBATO HEADTIRE FARTHINGALE STOCKINGS & GARTERS WIG SMOCK 2 3 4 5 Contents Introduction: Early Modern Dress 9 Archduchess Isabella 11 Isabella undressing / dressing guide 12 Early Modern Materials 38 6 7 Introduction Early Modern Dress For men as well as women, movement was restricted in the Early Modern period, and as you’ll discover, required several The era of Early Modern dress spans between the 1500s to pairs of hands to put on. the 1800s. In different countries garments and tastes varied hugely and changed throughout the period. Despite this variation, there was a distinct style that is recognisable to us today and from which we can learn considerable amounts in terms of design, pattern cutting and construction techniques. Our focus is Europe, particularly Belgium, Spain, Austria and the Netherlands, where our characters Isabella and Albert lived or were connected to during their reign. This booklet includes a brief introduction to Isabella and Albert and a step-by-step guide to undressing and dressing them in order to gain an understanding of the detail and complexity of the garments, shoes and accessories during the period. The clothes you see would often be found in the Spanish courts, and although Isabella and Albert weren’t particularly the ‘trend-setters’ of their day, their garments are a great example of what was worn by the wealthy during the late 16th and early 17th centuries in Europe. -

Andromeda Unbound’Revisited REVIEW ARTICLE Dutch Crossing © W.S.Maney& Sonltd2013 Illustrated Catalogue

dutch crossing, Vol. 37 No. 2, July 2013, 188–90 REVIEW ARTICLE ‘Andromeda Unbound’ Revisited Raingard Esser University of Groningen, The Netherlands Dynasty and Piety. Archduke Albert (1598–1621) and Habsburg Political Culture in the Age of Religious War. By Luc Duerloo. Farnham: Ashgate. 2012; Isabel Clara Eugenia. Female Sovereignty in the Courts of Madrid and Brussels. Edited by Cordula van Wyhe. London: Paul Holberton Publishing in association with Centro de Eustudios Europa Hispánica, Madrid. 2012. In autumn 1998 the Royal Museums for Art and History in Brussels opened a major exhibition commemorating the 400th anniversary of the reign of Archdukes Albert and Isabella in the Southern Netherlands. The exhibition was accompanied by an impressive and beautifully illustrated catalogue.1 Historians, art historians, and literary scholars examined the cosmo- politan court in Brussels and its impact on the fl ourishing arts and culture created by the Habsburg couple to echo the Burgundian splendour of the past and to mount a Counter- Reformation campaign on the frontlines of the confessional divide of the Low Countries. The introductory chapter by Werner Thomas, from which the title of the present review article is borrowed, refl ects the high expectations in the Southern Netherlands expressed at the arrival of the Archducal couple in 1598. For a number of scholars involved in this project, the topic remained of lasting interest and has resulted in new research into a hitherto neglected fi eld of study. This new interest in the politics and culture of the Southern Netherlands in the fi rst half of the seventeenth century is enriched by the highly international outlook and expertise of these scholars and by their knowledge of the wider Habsburg world well beyond the confi nes of the seventeen provinces of the Low Countries. -

Tamar Cholcman, Views of Peace and Prosperity – Hopes for Autonomy

RIHA Journal 0040 | 20 June 2012 Views of Peace and Prosperity – Hopes for Autonomy and Self- Government, Antwerp 1599 amar !"olcman #diting and peer review managed by& Simon Laevers, Institut Royal du Patrimoine Artistique – oninli!" Instituut voor #et unst$atrimonium %IRPA& I ', (russels 'eviewers& Ral$# )ekonin*", +atasja Peeters A%stract In Flanders, the Entry of a new ruler into one of the cities of his domain (Joyeuse Entrée) transformed the urban landscape into a visual pamphlet – an opportunity to lay out the most urgent needs, hopes and demands of the people through a series of ephemeral monuments and civic ceremonies. The triumphal procession of the rchdu!es lbert and Isabella into ntwerp in "#$$, was li!ewise used by the city and by the creator of the pageant, humanist and city secretary %ohannes &ochius, to lay out the main concerns and worries of their time. The article focuses on two of the monuments and the two ceremonies of oath taking in order to reveal the use of the pageant's structure as a 'progressing viewing e(perience'. The consideration of the viewing order reveals not only the strive for peace and the call to establish a self)governmental system under the rule of the new governors, but also the political thought of the time and the surprising demand to establish a mi(ed government, containing the fundaments of aristocracy and democracy within the monarchic rule of *pain. !ontents Introduction, -#e -rium$#al .ntry o/ t#e Ar*#duke Al0ert and t#e In/anta Isa0ella 1lara .u2enia into Ant3er$, 1455 6ar and )iscontent, -

The Portrait of Doña Maria De' Medici by Frans Pourbus the Younger

The Portrait of doña Maria de’ Medici by Frans Pourbus the Younger or, the Habsburg temptation at the French court Blaise Ducos Testu hau Creative Commons lizentziapean (mota: Aitortu–EzKomertziala-LanEratorririkGabe) argitaratu da (by-nc-nd) 4.0 international. Beraz, berau banatu, kopiatu eta erreproduzitu daiteke (edukian aldaketarik egin gabe), betiere, irakaskuntza edo ikerketarako helburuekin, eta egilea eta jatorria aitortuta. Ezin da merkataritza helburuetarako erabili. Lizentzia honen baldintzak http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncnd/4.0/legalcode webgunean kontsultatu daitezke. Ezin dira irudiak erabili eta erreproduzitu, argazkien eta/edo lanen egile-eskubideen jabeek berariazko baimena eman ezean. © of the texts: Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao Photography credits © Bibliothèque nationale de France: figs. 6 and 7 © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao: figs. 1, 3 and 4 © Kunsthistorisches Museum mit MVK und ÖTM: fig. 2 © Museo Nacional del Prado: fig. 8 © RMN / Thierry Le Mage: fig. 5 © RMN / Hervé Lewandowski: figs. 12 and 13 © Sistema Museale Civico della citta’ di Vicenza: fig. 10 © 2010. Photo Scala, Florence - courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali: fig. 9 Text published in: B’09 : Buletina = Boletín = Bulletin. Bilbao : Bilboko Arte Eder Museoa = Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao = Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, no. 5, 2010, pp. 109-137. 2 A Flemish portrait painted in Italy ntil now, the Portrait of doña Maria de’ Medici in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum [fig. 1] has apparently been the object of some confusion1. And by this I am not referring to the old attribution of the work Uto Gheeraerts, with which it came onto the art market in the mid-1950s, but rather to a more diffi- cult question2: the date it was actually painted. -

Observing Protest from a Place

12 VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Griffey (ed.) Sartorial Politics in Early Modern Europe Edited by Erin Griffey Sartorial Politics in Early Modern Europe Fashioning Women FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Sartorial Politics in Early Modern Europe FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late me- dieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes monographs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seemingly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Sartorial Politics in Early Modern Europe Fashioning Women Edited by Erin Griffey Amsterdam University Press FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Cover illustration: Jacob Heinrich Elbfas, Christina as a young regent under guardianship, 1637, oil on canvas. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Newgen/Konvertus isbn 978 94 6298 600 8 e-isbn 978 90 4853 724 2 doi 10.5117/9789462986008 nur 685 © E. -

The House of Vasa the House of Austria

The House of Vasa and The House of Austria The House of Vasa and The House of Austria Correspondence from the Years 1587 to 1668 Part I The Times of Sigismund III, 1587–1632 Volume 1 Edited by Ryszard Skowron in collaboration with Krzysztof Pawłowski, Ryszard Szmydki, Aleksandra Barwicka, Miguel Conde Pazos, Friedrich Edelmayer, Rubén González Cuerva, José Martínez Millán, Tomasz Poznański, Manuel Rivero Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego • Katowice 2016 Research financed by the Minister for Science and Higher Education through the National Programme for the Development of Humanities No. 12H 11 0017 80 Reviewer: Professor Mariusz Markiewicz, Ph.D. Editor Ryszard Skowron English Translation Łukasz Borowiec Margerita Beata Krasnowolska Piotr Krasnowolski Proofreading of Latin Texts Krzysztof Pawłowski Design & DTP Renata Tomków Copyright © 2016 by Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego All rights reserved ISBN 978-83-8012-959-7 Published by Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego ul. Bankowa 12B, 40-007 Katowice www.wydawnictwo.us.edu.pl e-mail: [email protected] Printed and Bound by „TOTEM.COM.PL Sp. z o.o.” Sp.K ul. Jacewska 89 88-100 Inowrocaw CONTENTS INTRODUCTION RYSZARD SKOWRON The House of Vasa and the House of Austria: Correspondence from 1587– 1668. Project description. ............................................. 21 JOSÉ MARTÍNEZ MILLÁN The Habsburg Dynasty during the Seventeenth Century: The Ideological Construction of a Universal Political Entity. 37 RYSZARD SZMYDKI Sigismund III Vasa and the Netherlands. 69 MIGUEL CONDE PAZOS The Hispanic Monarchy Facing the Accession of the Vasa Monarchy. Don Guillén de San Clemente’s Embassy to Poland (1588–1589). 95 RUBÉN GONZÁLEZ CUERVA The Spanish Embassy in the Empire, Watchtower of Poland (1590–1624). -

The Fleeting Structures of Early Modern Europe

From the Library: The Fleeting Structures of Early Modern Europe February 4 – July 29, 2012 National Gallery of Art From the Library: The Fleeting Structures of Early Modern Europe For centuries, the world has seen its cities enrobed in festive garb for all manner of honorary events. Today, urban centers find themselves revitalized and beautified to host the Olympic Games or celebrate a national holiday. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, world’s fairs and exhibitions gave cities the opportunity to demonstrate their strengths to the world through public display. In early modern Europe, state visits, corona- tions, and weddings were among the occasions that provided a city the occasion to stage a lavish production. Artists and architects designed structures and decorations by commis- sion, affording them the chance to experiment with new ideas or encourage city officials to consider new uses of public space. Today, scholars who are interested in the architectural developments of the past face a distinct obstacle in their research: the fact that many of the structural apparatus built for these festivals were not permanent. In a few cases, a structure proved popular or impor- tant enough to be rebuilt in a more durable form; typically, however, they were designed to stand for only a few weeks. Wooden and papier-mâché constructions were quickly disas- sembled, depriving contemporary researchers of the opportunity to examine them in their original context. Before movable type was introduced in the mid-fifteenth century, the only method of documenting such events was through drawings and handwritten descrip- tions, which rarely survive today.