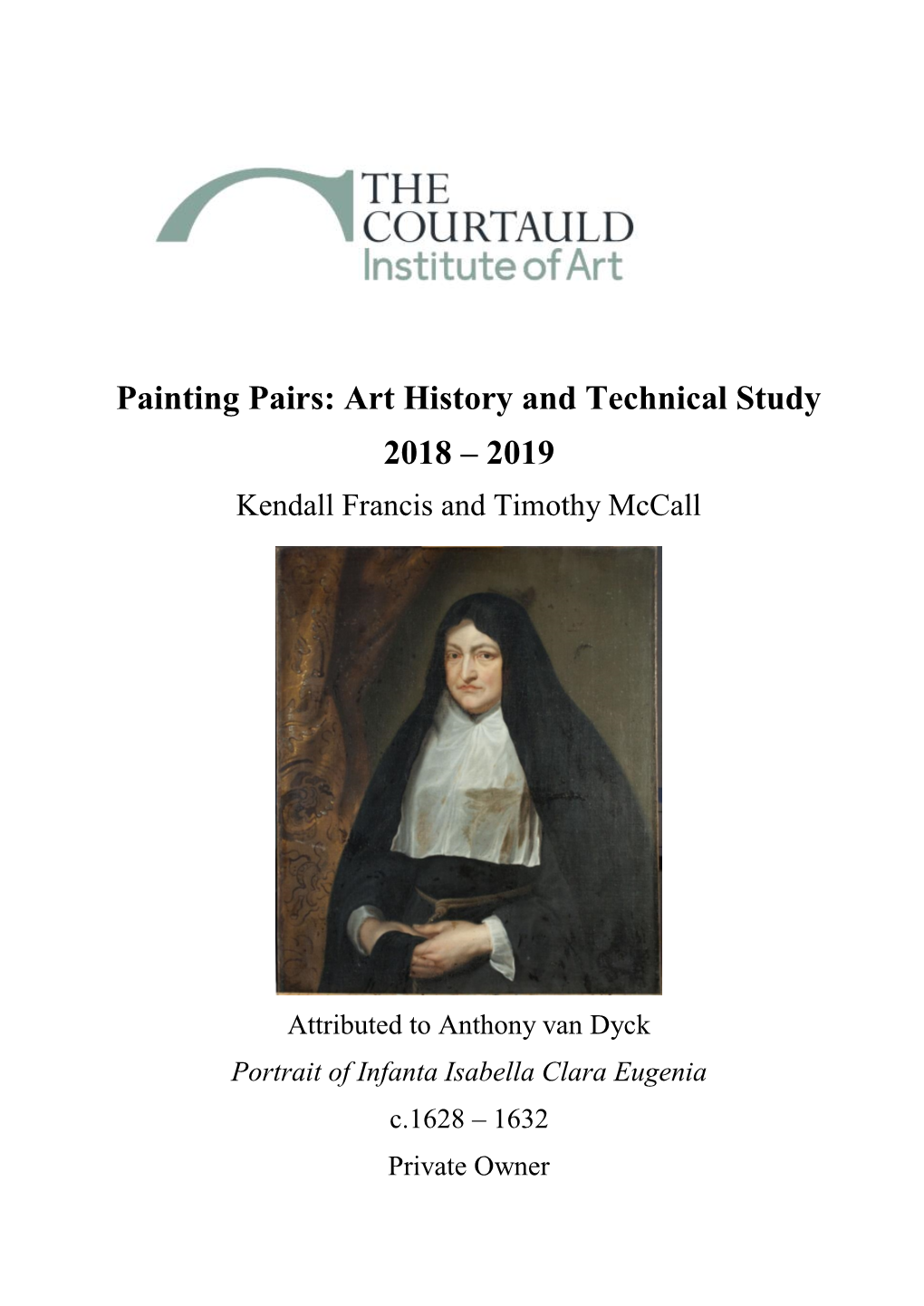

Infanta Isabella, Attributed to the Workshop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogo.Pdf

ART HISTORY NATURE FOOD & DRINK CINEMA PHOTOGRAPHY HOBBY SPORT HISTORY OF ART 28 History and Figures of the Church 35 The Contemporary Mosaic 45 Contents The First Civilizations 28 Techniques and Materials Bulgari 45 The Classical World 28 of the Arts 35 Gucci 45 The Early Middle Ages 28 The Romanesque 29 DICTIONARIES OF CIVILIZATION 36 SCRIPTS & ALPHABETS 46 Still Life 21 Goya 24 The Gothic 29 Arabic Alphabet 46 ART The Portrait 21 Leonardo 24 The 1400s 29 Oceania 37 Chinese Script 46 Islamic Art 28 Hieroglyphs 46 Art and Eroticism 21 Manet 24 Africa 38 The Painting of the Serenissima 10 Byzantine and Russian Art 28 Mayan Script 46 Landscape in Art 21 Mantegna 24 Celts, Vikings and Germans 38 The Renaissance 29 Japanese Alphabet 46 The Galleria Farnese Michelangelo 25 China 38 The Late 1500s 29 Hebrew Alphabet 46 of Annibale Carracci 11 GREAT MONOGRAPHS 22 Monet 25 Egypt 38 The Baroque 28 Musée d’Orsay 11 Bosch 22 Perugino 24 Etruscans 38 The Early 1700s 28 CULTURE GUIDES 47 Correggio. The Frescoes in Parma 11 Caravaggio 22 Piero della Francesca 24 Japan 38 The Age of the Revolutions 28 Archaeology 47 Botticelli 11 Cézanne 22 Raphael 25 Greece 38 Romanticism 28 Art 47 Goya 11 Gauguin 22 Rembrandt 24 India 38 The Age of Impressionism 28 Artistic Prints 47 Museum of Museums 11 Giotto 22 Renoir 24 Islam 38 American Art 28 Design 47 Goya 22 Tiepolo 24 Maya and Aztec 38 Nicolas Poussin Ethnic Art 47 Leonardo da Vinci 22 Tintoretto 24 The Avant-Gardes 29 Mesopotamy 38 Catalogue raisonné of the Paintings 12 Graphic Design 47 Michelangelo 22 Titian 25 Contemporary Art 28 Rome 38 Photography, Cinema, Design 28 Impressionism 47 Palladio. -

The Creation of a Secular Inquisition in Early Modern Brabant

Orthodoxy and Opposition: The Creation of a Secular Inquisition in Early Modern Brabant Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Christman, Victoria Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 08:36:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195502 ORTHODOXY AND OPPOSITION: THE CREATION OF A SECULAR INQUISITION IN EARLY MODERN BRABANT by Victoria Christman _______________________ Copyright © Victoria Christman 2005 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 5 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Victoria Christman entitled: Orthodoxy and Opposition: The Creation of a Secular Inquisition in Early Modern Brabant and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Professor Susan C. Karant Nunn Date: 17 August 2005 Professor Alan E. Bernstein Date: 17 August 2005 Professor Helen Nader Date: 17 August 2005 Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Isabel Clara Eugenia and Peter Paul Rubens’S the Triumph of the Eucharist Tapestry Series

ABSTRACT Title of Document: PIETY, POLITICS, AND PATRONAGE: ISABEL CLARA EUGENIA AND PETER PAUL RUBENS’S THE TRIUMPH OF THE EUCHARIST TAPESTRY SERIES Alexandra Billington Libby, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Directed By: Professor Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., Department of Art History and Archeology This dissertation explores the circumstances that inspired the Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia, Princess of Spain, Archduchess of Austria, and Governess General of the Southern Netherlands to commission Peter Paul Rubens’s The Triumph of the Eucharist tapestry series for the Madrid convent of the Descalzas Reales. It traces the commission of the twenty large-scale tapestries that comprise the series to the aftermath of an important victory of the Infanta’s army over the Dutch in the town of Breda. Relying on contemporary literature, studies of the Infanta’s upbringing, and the tapestries themselves, it argues that the cycle was likely conceived as an ex-voto, or gift of thanks to God for the military triumph. In my discussion, I highlight previously unrecognized temporal and thematic connections between Isabel’s many other gestures of thanks in the wake of the victory and The Triumph of the Eucharist series. I further show how Rubens invested the tapestries with imagery and a conceptual conceit that celebrated the Eucharist in ways that symbolically evoked the triumph at Breda. My study also explores the motivations behind Isabel’s decision to give the series to the Descalzas Reales. It discusses how as an ex-voto, the tapestries implicitly credited her for the triumph and, thereby, affirmed her terrestrial authority. Drawing on the history of the convent and its use by the king of Spain as both a religious and political dynastic center, it shows that the series was not only a gift to the convent, but also a gift to the king, a man with whom the Infanta had developed a tense relationship over the question of her political autonomy. -

Molto Più Di Una Vacanza

Molto più di una vacanza Gentile Ospite, a nome nostro e di tutto lo staff siamo lieti di porgerLe il più caloroso benvenuto e La ringraziamo di aver scelto il Giardinetto per soggiornare sul Lago d’Orta. La nostra casa è affacciata sulle acque del romantico lago d’Orta in un’oasi di tranquillità e relax. Siamo a pochi minuti dal centro di Orta San Giulio, dove scoprirà testimonianze storiche, artistiche e culturali. La invitiamo ad assaggiare la cucina mediterranea creativa e le specialità del nostro Ristorante, la nostra carta vini conta più di 300 etichette, italiane e non, per ogni piacevole occasione! Ci auguriamo che Lei possa trovare in questo luogo l’atmosfera di casa, la Sua tranquillità ed il Suo calore, con quel pizzico di charme in più che ci contraddistingue. Le ricordiamo inoltre che troverà a Sua disposizione piscina con acqua vitalizzata del circuito “Grander”, sdraio e ombrelloni per il Suo relax sul lago nonché la possibilità di praticare diversi sport acquatici. Dear Guest, on behalf of the staff and ourselves we have the pleasure of wishing you our warmest welcome and thank you for having chosen Hotel Giardinetto for your stay on Lake Orta. Our hotel is beautifully located in a romantic and quiet relaxing oasis. We are a few minutes away from Orta San Giulio where you can discover some of its history, art and culture. We invite you to taste the Mediterranean and creative local cuisine of our Restaurant, our great wine list has more than 300 labels for every special occasion! We hope that you can find here the same comfort you have at home, with the peaceful charm and warmth that sets us apart. -

Colnaghistudiesjournal Journal-01

EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Charles Avery Art Historian specializing in European Xavier F. Salomon Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator, The Frick Sculpture, particularly Italian, French and English. Collection, New York. Colin Bailey Director, Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Salvador Salort-Pons Director, President & CEO, Detroit Francesca Baldassari Art Historian. Institute of Arts. Piers Baker-Bates Visiting Research Associate in Art History, Jack Soultanian Conservator, The Metropolitan Museum of Colnaghi Studies Journal is produced biannually by the Colnaghi Foundation. Its purpose is Art, New York. The Open University. to publish texts on significant pre-twentieth-century artworks in the European tradition Bruce Boucher Director, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London. Nicola Spinosa Former Director of Museo di Capodimonte, Naples. that have recently come to light or about which new research is underway, as well as Till-Holger Borchert Director, Musea Brugge. Carl Strehlke Adjunct Emeritus, Philadelphia Museum of Art. on the history of their collection. Texts about artworks should place them within the Antonia Boström Keeper of Sculpture, Metalwork, Ceramics Holly Trusted Senior Curator of Sculpture, Victoria & Albert broader context of the artist’s oeuvre, provide visual analysis and comparative images. & Glass, Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Museum, London. Edgar Peters Bowron Former Audrey Jones Beck Curator of Manuscripts may be sent at any time and will be reviewed by members of the journal’s Benjamin van Beneden Director, Rubenshuis, Antwerp. European Art, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Editorial Committee, composed of specialists on painting, sculpture, architecture, Mark Westgarth Programme Director and Lecturer in Art History Xavier Bray Director, The Wallace Collection, London. -

A Constellation of Courts the Courts and Households of Habsburg Europe, 1555-1665

A Constellation of Courts The Courts and Households of Habsburg Europe, 1555-1665 A Constellation of Courts The Courts and Households of Habsburg Europe, 1555-1665 Edited by René Vermeir, Dries Raeymaekers, and José Eloy Hortal Muñoz © 2014 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium) All rights reserved. Except in those cases expressly determined by law, no part of this publication may be multiplied, saved in an automated datafile or made public in any way whatsoever without the express prior written consent of the publishers. ISBN 978 90 5867 990 1 e-ISBN 978 94 6166 132 6 D / 2014 / 1869 / 47 NUR: 685, 697 Cover illustration: Lucas I van Valckenborgh, “Frühlingslandschaft (Mai)”, (inv. Nr. GG 1065), Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna Contents Courts and households of the Habsburg dynasty: history and historiography José Eloy Hortal Muñoz, Dries Raeymaekers and René Vermeir 7 The political configuration of the Spanish Monarchy: the court and royal households José Martínez Millán 21 The court of Madrid and the courts of the viceroys Manuel Rivero 59 The economic foundations of the royal household of the Spanish Habsburgs, 1556–1621 Carlos Javier de Carlos Morales 77 The household of archduke Albert of Austria from his arrival in Madrid until his election as governor of the Low Countries: 1570–1595 José Eloy Hortal Muñoz 101 Flemish elites under Philip III’s patronage (1598-1621): household, court and territory in the Spanish Habsburg Monarchy* -

Introduction

Introduction Sarah Joan Moran and Amanda Pipkin The Low Countries, a region comprising modern-day Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and parts of eastern Germany and northern France, offers a re- markable laboratory for the study of early modern religion, politics, and cul- ture. Under the domain of the Hapsburg empire from 1482 and allocated to the Spanish crown when Holy Roman Emperor Charles V abdicated in 1555, the Low Countries were highly urbanized, literate, and cosmopolitan, and their cities were among the most important trade centers in Northern Europe. Following the publication of Luther’s 98 theses in 1517 the region also proved fertile ground for the spread of Protestant ideas, which combined with local resentment of foreign rule culminated in rebellion against Spain in 1568. This marked the start of the Eighty Years War.1 Philip II reestablished control over most of the Southern provinces around 1585 but neither he nor his successors were able to re-take the North. As war waged on for another six decades the South saw a wave of Catholic revival while Reformed evangelism flourished in the new Dutch Republic, entrenching a religious and political divide that slowly crushed the dreams of those hoping to reunite the Low Countries.2 Following the War of the Spanish Succession, under the Treaty of Rastatt in 1714 the Southern provinces were transferred back to the Austrian Habsburg emperors, and both North and South underwent economic declines as they 1 See Jonathan Irvine Israel, The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall, 1477–1806 (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1995); Arie-Jan Gelderblom, Jan L. -

Portraits, Pastels, Prints: Whistler in the Frick Collection

SELECTED PRESS IMAGES Van Dyck: The Anatomy of Portraiture March 2 through June 5, 2016 The Frick Collection, New York PRESS IMAGE LIST Digital images are available for publicity purposes; please contact the Press Office at 212.547.0710 or [email protected]. 1. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) Queen Henrietta Maria with Jeffery Hudson, 1633 Oil on canvas National Gallery of Art, Washington; Samuel H. Kress Collection 2. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) The Princesses Elizabeth and Anne, Daughters of Charles I, 1637 Oil on canvas Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh; purchased with the aid of the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Scottish Office and the Art Fund 1996 3. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) Mary, Lady van Dyck, née Ruthven, ca. 1640 Oil on canvas Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid 1 4. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) Charles I and Henrietta Maria Holding a Laurel Wreath, 1632 Oil on canvas Archiepiscopal Castle and Gardens, Kroměříž 5. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) Prince William of Orange and Mary, Princess Royal, 1641 Oil on canvas Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam 6. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) Pomponne II de Bellièvre, ca. 1637–40 Oil on canvas Seattle Art Museum 2 7. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) Margaret Lemon, ca. 1638 Oil on canvas Private collection, New York 8. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) Self-Portrait, ca. 1620–21 Oil on canvas The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Jules Bache Collection, 1949 9. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) Frans Snyders, ca. 1620 Oil on canvas The Frick Collection; Henry Clay Frick Bequest Photo: Michael Bodycomb 3 10. -

The Pitiful King: Tears, Blood, and Family in Revolutionary Royalism

The Pitiful King: Tears, Blood, and Family in Revolutionary Royalism Victoria Murano Submitted to Professors Lisa Jane Graham and Linda Gerstein In partial fulfillment of the requirement of History 400: Senior Thesis Seminar Murano 1 Abstract When the French Revolution erupted in 1789, revolutionaries strove to foster a sense of freedom of expression, guaranteeing a brief freedom of the press. The eleventh article of the 1791 Declaration of the Rights of Man asserts that “The free communication of thoughts and opinions is one of man’s most precious rights; all citizens may therefore speak, write, print freely, except to answer for the abuse of this liberty in cases determined by law.” However, as France became further embroiled in the Revolution, it abandoned its allegiance to the universality of these rights, propagating pro-republican thought, and persecuting anyone who did not share these views. The royalist press was a major concern to the new republican government, because it continued to speak out in support of the king and criticize the Revolution. The existence of royalist journalists and writers thus posed a problem for revolutionaries who wanted to establish a monolithically-minded republic. Therefore, over time, they enacted repressive censorship and punishment to crack down on royalist sympathizers. Although they sent many royalist writers to prison or the guillotine, the revolutionaries ultimately failed to silence their political enemies. This thesis uses newspapers, images, and other printed media to explore royalist coverage of three events that diminished royal power: Louis XVI’s flight to Varennes in June 1791, his execution in January 1793, and the death of his nine-year-old son and heir, Louis XVII, in June 1795. -

The Antiques Roadshow to Be Sold at Christie’S London on 8 July, 2014

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Friday, 30 May 2014 VAN DYCK HEAD STUDY RECENTLY REDISCOVERED ON THE ANTIQUES ROADSHOW TO BE SOLD AT CHRISTIE’S LONDON ON 8 JULY, 2014 London – Christie’s is pleased to announce that a striking head study by Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), which was recently re-discovered on the BBC television progamme The Antiques Roadshow, will be offered at Christie’s Old Master & British Paintings Evening Sale, on Tuesday 8 July (estimate: £300,000-500,000, illustrated above). This work is a preparatory sketch for van Dyck’s full-length group portrait of The Magistrates of Brussels, which was painted in Brussels in 1634-35, when the artist was at the height of his powers. The painting was bought 12 years ago by Father Jamie MacLeod from an antiques shop in Cheshire for just £400. The proceeds of the sale will go towards the acquisition of new church bells for Whaley Hall Ecumenical Retreat House in Derbyshire to commemorate the centenary of the end of the First World War. This work will be exhibited for the first time ahead of the sale when it goes on free public view at Christie’s New York on 31 May to 3 June; it will also be on view in London ahead of the sale, on 5 to 8 July. The sketch was largely obscured by later over-paint and, as a result, had been overlooked by van Dyck scholars. Recent cleaning and restoration of the picture has revealed a swiftly executed head study entirely consistent with three other known sketches for the Magistrates of Brussels picture, a work that hung in the Brussels Town Hall until it was destroyed during the French bombardment of the city in 1695. -

Mapmaking in England, Ca. 1470–1650

54 • Mapmaking in England, ca. 1470 –1650 Peter Barber The English Heritage to vey, eds., Local Maps and Plans from Medieval England (Oxford: 1525 Clarendon Press, 1986); Mapmaker’s Art for Edward Lyman, The Map- world maps maker’s Art: Essays on the History of Maps (London: Batchworth Press, 1953); Monarchs, Ministers, and Maps for David Buisseret, ed., Mon- archs, Ministers, and Maps: The Emergence of Cartography as a Tool There is little evidence of a significant cartographic pres- of Government in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chi- ence in late fifteenth-century England in terms of most cago Press, 1992); Rural Images for David Buisseret, ed., Rural Images: modern indices, such as an extensive familiarity with and Estate Maps in the Old and New Worlds (Chicago: University of Chi- use of maps on the part of its citizenry, a widespread use cago Press, 1996); Tales from the Map Room for Peter Barber and of maps for administration and in the transaction of busi- Christopher Board, eds., Tales from the Map Room: Fact and Fiction about Maps and Their Makers (London: BBC Books, 1993); and TNA ness, the domestic production of printed maps, and an ac- for The National Archives of the UK, Kew (formerly the Public Record 1 tive market in them. Although the first map to be printed Office). in England, a T-O map illustrating William Caxton’s 1. This notion is challenged in Catherine Delano-Smith and R. J. P. Myrrour of the Worlde of 1481, appeared at a relatively Kain, English Maps: A History (London: British Library, 1999), 28–29, early date, no further map, other than one illustrating a who state that “certainly by the late fourteenth century, or at the latest by the early fifteenth century, the practical use of maps was diffusing 1489 reprint of Caxton’s text, was to be printed for sev- into society at large,” but the scarcity of surviving maps of any descrip- 2 eral decades. -

Rare Masterwork by Spanish Court Painter Vicente López Acquired by Meadows Museum

RARE MASTERWORK BY SPANISH COURT PAINTER VICENTE LÓPEZ ACQUIRED BY MEADOWS MUSEUM Portrait of Influential American Merchant Richard Worsam Meade, First Major Collector of Spanish Art in U.S. Painting To be Unveiled May 10, and Featured in Exhibition of Top Acquisitions In Fall 2011 Dallas, TX, May 9, 2011 – A rare portrait of influential American merchant and naval agent Richard Worsam Meade—the first major collector of Spanish art in the U.S.—will be made accessible to the public in its new home at the Meadows Museum at Southern Methodist University. On May 10, the museum will unveil the masterwork by Vicente López, one of the most significant painters of the Spanish Enlightenment. Acquired with the generous support of six donors from the Dallas community, the unpublished painting will add depth to the museum’s holdings of work by this celebrated court painter and will provide insight into a legendary American family. Meade was the son of the Philadelphia Revolutionary George Meade, and his son, George Gordon Meade – better known as General Meade – went on to defeat Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg. Around 1800, Richard Worsam Meade moved his export business to the port city of Cádiz, Spain where he began to collect paintings as currency for debts. It was there that Meade developed one of the most outstanding private collections of Spanish art, including paintings by Titian, Correggio, Veronese, Rubens, Van Dyck, Velázquez, and Murillo, and ultimately became the first American collector known to have owned a painting by Murillo. “Meade could in many ways be considered the earliest predecessor of our museum’s founder, Algur H.