The Fleeting Structures of Early Modern Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ttrickrarebooks.Com Member ABAA, SLAM & ILAB B MK A G Hard Hat Area

Thinking straight . No. . No. (outside front cover). The beauty in science (title-page). No. . R I C K T T R I A c K R E M B E O C O U K R S B C 7 A 5 T A L O G Sabine Avenue Narberth, Pennsylvania Tel. -- Fax -- info @mckittrickrarebooks.com www.mckittrickrarebooks.com Member ABAA, SLAM & ILAB B MK A G Hard Hat Area . No. 1. Alberti, Leone Battista. De Re Aedificatoria . Florence, Nicolaus Lau - rentii Alamanus December . Folio ( x mm.). [ ] leaves. Roman type ( Rb), lines per page (a few leaves or ), seven-line capital spaces with printed guide letters, most quires with printed catch - words, some quire signatures printed on the last line of text. th-century Italian vellum over stiff paper boards, ms. spine title, edges sprinkled brown. See facing illustration .$ . First Edition, first state: “ ” (PMM ). This is the first exposition of the scientific theo - ries of the Renaissance on architecture, the earliest printed example of town planning, the first description in the Renaissance of the ideal church and the first printed proposals for hospital design. He discusses frescoes, marble sculpture, windows, staircases, prisons, canals, gardens, machinery, warehouses, markets, arsenals, theaters…. He advocates for hospitals with small private rooms, not long wards, and with segregated facilities for the poor, the sick, the contagious and the noninfectious. “ ” ( PMM ), as well as important restoration projects like the side aisles of Saint Peter’s in Rome. A modest copy (washed, portions of six margins and one corner supplied, three quires foxed, scattered marginal spotting, loss of a half dozen letters, a few leaves lightly stained, two effaced stamps), book - plate of Sergio Colombi with his acquisition date of .X. -

PNWA E-Notes

PNWA E-Notes http://ui.constantcontact.com/visualeditor/visual_editor_preview.jsp?agent... Having trouble viewing this email? Click here You may unsubscribe if you no longer wish to receive our emails. PACIFIC NORTHWEST WRITERS ASSOCIATION MARCH E-NOTES March E-Notes MARCH 2010 E-NOTES: PNWA News E-Notes is your monthly electronic newsletter full of the latest news about the literary world. Our newsletter is a PNWA Member Benefit. Contests/Submissions Classes/Workshops Please send us an email if you would like to place an announcement in next month's E-Notes: [email protected] Events/Speakers Miscellaneous (Announcements must be received by the 19th of the previous month to be included). PNWA NEWS: MONTHLY SPEAKER MEETING: Thursday, March 18, 2010 Chinook Middle School @ 7:00 P.M. (2001 98th Ave NE, Bellevue, WA 98004) Topic & Speaker will be announced soon on the main page of our website (www.pnwa.org). PNWA Member Peter Bacho Leaving Yesler, Pleasure Boat Studio, Softcover $16.00 (250pp) (ISBN#: 978-1-929355570) Leaving Yesler encounters seventeen year-old Bobby Vincente in the wake of his older brother's military death; faced with the challenge of caring for his aging father, this young man from urban Seattle's housing projects is forced to take control of his life and identity as he traverses a period of life-altering change marked by new interests, new challenges, and ultimately, new life. Author Peter Bacho, a two-time winner of the American Book Award, explores themes of belief/disbelief, arrival/departure, and love/violence, through which he achieves a portrait of embodied strength in his protagonist. -

Isabel Clara Eugenia and Peter Paul Rubens’S the Triumph of the Eucharist Tapestry Series

ABSTRACT Title of Document: PIETY, POLITICS, AND PATRONAGE: ISABEL CLARA EUGENIA AND PETER PAUL RUBENS’S THE TRIUMPH OF THE EUCHARIST TAPESTRY SERIES Alexandra Billington Libby, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Directed By: Professor Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., Department of Art History and Archeology This dissertation explores the circumstances that inspired the Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia, Princess of Spain, Archduchess of Austria, and Governess General of the Southern Netherlands to commission Peter Paul Rubens’s The Triumph of the Eucharist tapestry series for the Madrid convent of the Descalzas Reales. It traces the commission of the twenty large-scale tapestries that comprise the series to the aftermath of an important victory of the Infanta’s army over the Dutch in the town of Breda. Relying on contemporary literature, studies of the Infanta’s upbringing, and the tapestries themselves, it argues that the cycle was likely conceived as an ex-voto, or gift of thanks to God for the military triumph. In my discussion, I highlight previously unrecognized temporal and thematic connections between Isabel’s many other gestures of thanks in the wake of the victory and The Triumph of the Eucharist series. I further show how Rubens invested the tapestries with imagery and a conceptual conceit that celebrated the Eucharist in ways that symbolically evoked the triumph at Breda. My study also explores the motivations behind Isabel’s decision to give the series to the Descalzas Reales. It discusses how as an ex-voto, the tapestries implicitly credited her for the triumph and, thereby, affirmed her terrestrial authority. Drawing on the history of the convent and its use by the king of Spain as both a religious and political dynastic center, it shows that the series was not only a gift to the convent, but also a gift to the king, a man with whom the Infanta had developed a tense relationship over the question of her political autonomy. -

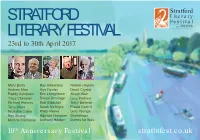

Strat-Lit-Fest-2017-Programme.Pdf

Stratford Literary STRATFORD Festival LITERARY FESTIVAL with 23rd to 30th April 2017 Mary Berry Roy Hattersley Natalie Haynes Andrew Marr Alys Fowler David Crystal Paddy Ashdown Ken Livingstone Alison Weir Tracy Chevalier Simon Armitage Lucy Parham Richard Holmes Rob Biddulph Tracy Borman Terry Waite Sarah McIntyre Planet Earth II Nicholas Crane Philip Reeve Gary Younge Roy Strong Horrible Histories Workshops Malorie Blackman Anthony Holden Events for Kids 10 th Anniversary Festival stratlitfest.co.uk BAILLIE GIFFORD LITERARY FESTIVAL SPONSORSHIP IMAGINATION, INSPIRATION AND A COMMITMENT TO THE FUTURE. Baillie Gifford is delighted to continue to sponsor some of the most renowned literary festivals throughout the UK. We believe that, much like a classic piece of literature, a great investment philosophy will stand the test of time. Baillie Gifford is one of the UK’s largest independent investment trust managers. In our daily work in investments we do our very best to emulate the imagination, insight and intelligence that successful writers bring to the creative process. In our own way we’re publishers too. Our free, award-winning Trust magazine provides you with an engaging and insightful overview of the investment world, along with details of our literary festival activity throughout AT BAILLIE GIFFORD WE the UK. BELIEVE IN THE VALUE OF GREAT LITERATURE 7RÛQGRXWPRUHRUWRWDNHRXWDIUHH AND IN LONG-STANDING subscription for Trust magazine, please call SUCCESS STORIES. us on 0800 280 2820 or visit us at www.bailliegifford.com/sponsorship Long-term investment partners Your call may be recorded for training or monitoring purposes. Baillie Gifford Savings Management Limited (BGSM) produces TrustNBHB[JOFBOEJTBOBGåMJBUFPG#BJMMJF(JGGPSE$P-JNJUFE XIJDIJTUIF manager and secretary of seven investment trusts. -

Creative Writers Tue, April 4

BAYOU CITY BOOK FESTIVAL PRESENTED BY April 3 - 8, 2017 LoneStar.edu/Book-Festival LOCATIONS Willis N Montgomery FM 1484 1 LSC-CyFair 2 LSC-Kingwood Conroe Splendora Magnolia RESEARC H FO RE 3 ST Center for the Arts Building 20000 Kingwood Dr. The Woodlands 9191 Barker Cypress Rd. Kingwood, TX 77339 L New Caney H A Cypress, TX 77433 281.312.1600 D N E K Y U K 281.290.3200 G N I L S O 5 G 3 LSC-Montgomery 4 LSC-North Harris Tomball Kingwood Spring SPRING STUEBNER 2 KINGWOOD D RIVE Klein A ETT LOU 4 W L A K E WW THORNE Humble H A O L U D S Building G Student Services Building I N T 6 E O N W E P S K 3200 College Park Dr. 2700 W.W. Thorne Dr. T W F I Y E L G D RA WILL CLAYTON PARKWAY Conroe, TX 77384 Houston, TX 77073 CyFair NT Y R R 936.273.7000 281.618.5400 E P S S E R P Y LAKESHORE C R E LAN G 5 LSC-Creekside Center 6 LSC-University Park 1 K DIN R A Aldine B WEST ROAD SPENCER / HWY 529 TH VICTORY W LITTLE YORK W LITTLE YORK SOU CLAY ROAD D A O 8747 West New Harmony Trail Commons Building R Y R F The Woodlands, TX 77375 20515 SH 249 832.761.6600 Houston, TX 77070 Downtown 281.290.2600 Houston CONTENTS P4 P6 P8 Monday-Thursday Saturday Main Day Children’s Zone At-A-Glance Schedule At-A-Glance Schedule At-A-Glance Schedule BAYOU CITY BOOK FESTIVAL P29 P30 P33 PRESENTED BY Event Exhibitors Event Sponsors Event Partners The Bayou City Book Festival presented by Lone Star College held its P34 P36 inaugural festival on April 8-9, 2016 under the name of the Lone Star Book Open Space Open Space Festival. -

A Constellation of Courts the Courts and Households of Habsburg Europe, 1555-1665

A Constellation of Courts The Courts and Households of Habsburg Europe, 1555-1665 A Constellation of Courts The Courts and Households of Habsburg Europe, 1555-1665 Edited by René Vermeir, Dries Raeymaekers, and José Eloy Hortal Muñoz © 2014 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium) All rights reserved. Except in those cases expressly determined by law, no part of this publication may be multiplied, saved in an automated datafile or made public in any way whatsoever without the express prior written consent of the publishers. ISBN 978 90 5867 990 1 e-ISBN 978 94 6166 132 6 D / 2014 / 1869 / 47 NUR: 685, 697 Cover illustration: Lucas I van Valckenborgh, “Frühlingslandschaft (Mai)”, (inv. Nr. GG 1065), Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna Contents Courts and households of the Habsburg dynasty: history and historiography José Eloy Hortal Muñoz, Dries Raeymaekers and René Vermeir 7 The political configuration of the Spanish Monarchy: the court and royal households José Martínez Millán 21 The court of Madrid and the courts of the viceroys Manuel Rivero 59 The economic foundations of the royal household of the Spanish Habsburgs, 1556–1621 Carlos Javier de Carlos Morales 77 The household of archduke Albert of Austria from his arrival in Madrid until his election as governor of the Low Countries: 1570–1595 José Eloy Hortal Muñoz 101 Flemish elites under Philip III’s patronage (1598-1621): household, court and territory in the Spanish Habsburg Monarchy* -

Introduction

Introduction Sarah Joan Moran and Amanda Pipkin The Low Countries, a region comprising modern-day Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and parts of eastern Germany and northern France, offers a re- markable laboratory for the study of early modern religion, politics, and cul- ture. Under the domain of the Hapsburg empire from 1482 and allocated to the Spanish crown when Holy Roman Emperor Charles V abdicated in 1555, the Low Countries were highly urbanized, literate, and cosmopolitan, and their cities were among the most important trade centers in Northern Europe. Following the publication of Luther’s 98 theses in 1517 the region also proved fertile ground for the spread of Protestant ideas, which combined with local resentment of foreign rule culminated in rebellion against Spain in 1568. This marked the start of the Eighty Years War.1 Philip II reestablished control over most of the Southern provinces around 1585 but neither he nor his successors were able to re-take the North. As war waged on for another six decades the South saw a wave of Catholic revival while Reformed evangelism flourished in the new Dutch Republic, entrenching a religious and political divide that slowly crushed the dreams of those hoping to reunite the Low Countries.2 Following the War of the Spanish Succession, under the Treaty of Rastatt in 1714 the Southern provinces were transferred back to the Austrian Habsburg emperors, and both North and South underwent economic declines as they 1 See Jonathan Irvine Israel, The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall, 1477–1806 (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1995); Arie-Jan Gelderblom, Jan L. -

The Portrait of Juana of Austria in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum

IN THE KING’S NAME The Portrait of Juana of Austria in the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum Leticia Ruiz Gómez This text is published under an international Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Creative Commons licence (BY-NC-ND), version 4.0. It may therefore be circulated, copied and reproduced (with no alteration to the contents), but for educational and research purposes only and always citing its author and provenance. It may not be used commercially. View the terms and conditions of this licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncnd/4.0/legalcode Using and copying images are prohibited unless expressly authorised by the owners of the photographs and/or copyright of the works. © of the texts: Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao Photography credits © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao: fig. 1 © Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien: fig. 7 © Musées Royaux des Beaux Arts de Belgique, Bruxelles: fig. 4 © Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid: figs. 2, 3, 5, 9 and 10 © Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid: figs. 6 and 8 Text published in: B’06 : Buletina = Boletín = Bulletin. Bilbao : Bilboko Arte Eder Museoa = Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao = Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, no. 2, 2007, pp. 85-123. Sponsored by: 2 n the 1550s Princess Juana of Portugal was a regular subject for portrait artists, being one of the leading women in the House of Austria, the dynasty that dominated the political scene in Europe throughout the I16th century. The youngest daughter of Charles V and Isabella of Portugal, she had a special role to play in her father’s geopolitical strategies, first as the wife of the heir to the Portuguese throne, to whom she bore a posthumous son who would eventually come to the throne of Spain’s neighbour, and subsequently as regent of the Emperor’s peninsular territories. -

Festival Handbook

This booklet was inspired by and written for participants in the Festival Encouragement Project (FEP), a program co-created in 2003 by the Center for Cultural Innovation and supported by a grant from the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs (LADCA). The goal of 2 the FEP is to build the strength and capacity of selected outdoor cultural celebrations produced in L.A. that serve residents and tourists. Book Photography: Aaron Paley Book Design: Peter Walberg Published by the Center for Cultural Innovation TABLE OF CONTENTS Artists shown on the following pages: INTRODUCTION Judith Luther Wilder Cover Dragonfly by Lili Noden’s Dragon Knights ONE Festivals: Their Meaning and Impact in the City of Angels Page 2 Titus Levi, PhD. Jason Samuels Smith, Anybody Can Get It TWO Page 4 A Brief Historical Overview of Selected Festivals in Los Angeles- 1890-2005 Nathan Stein Aaron Paley Page 6 THREE Tracy Lee Stum Madonnara, Street painter Why? An Introduction to Producing a Festival Hope Tschopik Schneider Page 7 Saaris African Foods FOUR Santa Monica Festival 2002 Choosing Place: What Makes a Good Festival Site? Page 9 Maya Gingery Procession, streamers by Celebration Arts Holiday Stroll in Palisades Park, FIVE Santa Monica Timelines & Workplans Page 11 Aaron Paley Body Tjak, created by I Wayan Dibia and Keith Terry SIX Santa Monica Festival 2002 The Business Side of Festivals Sumi Sevilla Haru Page 12 Ricardo Lemvo and Makina Loca on stage at POW WOW SEVEN Grand Avenue Party 2004 Public Relations Advice for Festival Producers -

I GLADLY STRAINED MY EYES to FOLLOW YOU — Entrance Hall — the Landing

a guided tour of Pollock House by Shauna McMullan I GLADLY STRAINED MY EYES TO FOLLOW YOU — Entrance Hall — The Landing UNKNOWN LADY UNKNOWN dates unknown dates unknown Karen Cornfield, House Manager, Pollok House Kate Davis, artist Is that a fly on her nose? Untitled It’s not meant to be there. Unasked There’s meant to be a story, Unspoken The person behind the face. Unkempt Unaccustomed This portrait of a woman was painted by a man. Unseen We know about him, not about her. Unsteady Unnecessary “He had a name and was born on a date. He came from a Unwilling country and was born in a place. He painted things that were Unemployed typical of the time. He went to a city and another country. His Unwise work is exhibited among the work of other men. His most Undressed famous work is a painting.” Ungovernable Unsound (But, not this one.) Unhealthy Unflappable When was she born and where did she live? Unlucky Where did she travel and what did she see? Unmarked Where can we see her life’s work? Unpretentious What was her passion? Unsightly What did she love? Unprincipled Unable Separated from her story, Unnatural Captured in a frame, Unwritten Hung upon a wall, Unbending To be remembered without a name. Unreasonable Unsettled Unstable — Silver Corridor Unaware Uncommunicative ANNE MARIE CHARLOTTE CORDAY Unwholesome Unsaid 1768 – 1793 Untapped Dr. Sarah Tripp, artist Unbecoming Unarmed Moods did not settle upon her face. When I arrived Untold (when I first saw her) this was the case – no mood. -

Download the Maple Festival the Adventures of Sophie Mouse Pdf Ebook by Poppy Green

Download The Maple Festival The Adventures of Sophie Mouse pdf ebook by Poppy Green You're readind a review The Maple Festival The Adventures of Sophie Mouse ebook. To get able to download The Maple Festival The Adventures of Sophie Mouse you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite books in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this ebook on an database site. Ebook Details: Original title: The Maple Festival (The Adventures of Sophie Mouse) Age Range: 5 - 9 years Grade Level: Kindergarten - 4 Series: The Adventures of Sophie Mouse (Book 5) 128 pages Publisher: Little Simon (October 13, 2015) Language: English ISBN-10: 1481441965 ISBN-13: 978-1481441964 Product Dimensions:5.5 x 0.3 x 7.3 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 7848 kB Description: Sophie Mouse is so excited to help her mother bake treats for Silverlake Forest’s big Maple Festival in the fifth book of The Adventures of Sophie Mouse.It’s finally fall in Silverlake Forest, and that means it’s time for the annual Maple Festival! The animals have heard it is going to be the biggest one yet with games, rides and, of course, Lily Mouse’s... Review: Adorable- innocent and charming. Warm and cozy for Fall. My daughter loves cozy seasonal books, and this fit the bill. Young girls can easily sympathize with the sweet mouse protagonist, drawing the reader in to her simple yet compelling storyline. My daughter really enjoyed this. -

Book Festival Organizers Toolkit

Book Festival Organizers Toolkit Produced by the Empire State Center for the Book with support from the New York Council for the Humanities Table of Contents Getting Started 1 Determining Your Vision/Purpose and Setting Goals 2 Forming Committees and Dividing Responsibilities 4 Choosing a Date and Securing a Venue 5 Formulating a Working Budget/Financial Considerations 7 Deciding on the Audience/Recruiting Presenters & Vendors 8 Determining the Programming Format and Schedule 10 Finding Potential Grants, Sponsors, and Partners 13 Establishing a Working Timeline 16 Promoting the Festival 18 Evaluating the Festival 20 Sample Forms/Templates 21 New York Council for the Humanities Grant Guidelines 26 Getting Started This toolkit is intended to serve as a guide to aid in the development, promotion, and execution of book festivals that celebrate writers, books, and literacy across New York State. A book festival is a series of one-time, unique events which builds community and sparks the imagination of its attendees as they interact with the participating authors and illustrators who have contributed to our literary culture and are all gathered in one place on the same day. Most book festivals are open to the public for free, so it is necessary to obtain presenters who are willing to come for free or possibly for just reasonable travel expenses, including a keynote speaker if there is one. Since a book festival is planned from the ground up, listed below are the areas that will help in organizing one. None of them are mutually exclusive of the others. Each item will be addressed within the toolkit.