Cross-Communal Sporting Projects and Inter-Group Relations Written by Christopher Rickard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writ the Journal of the Law Society of Northern Ireland Issue 205 Winter 2010/11

THE WRIT THE JOURNAL OF THE LAW SOCIETY OF NORTHERN IRELAND ISSUE 205 WINTER 2010/11 THIS MONTH Brian H Speers new President of the Law Society Title Insurance Risks Experts for Experts Please find below a list of standard title insurance risks which are covered by First Title: • Absent Landlord • Lack of Listed Building Consent • Adverse Possession • Lack of Planning Permission • Bankruptcy / Insolvency – Gratuitous Alienations • Limited / No Title Guarantee • Building Over a Sewer • Local Authority Search • Contaminated Land / Environmental Policies • Missing Deeds / Leases • Contingent Buildings (covering defective insurance provisions) • Missing Matrimonial Homes Consent • Defective Lease • Outstanding Charges Entry • Exceptions and Reservations- Know and Unknown • Possessory / Qualified Title • Flying Creeping / Freehold • Pre-Emption Rights • Forced Removal / Obstruction of a Right of Way • Profits à Prendre • Good Leasehold • Rent Charge • Judicial Review • Restrictive Covenants- Known and Unknown • Lack of Building Regulations Consent • Rights of Light • Lack of Easement – Access/ Drainage / Service Media / • Title Subject to a Lease Water Supply / Visibility Splay Supplemental cover is also available for loss of profits, consequential loss, rental liability, inflation and portfolio risks. To discuss one of the above listed risks or for a general enquiry please contact your DEDICATED UNDERWRITING TEAM – NORTHERN IRELAND Direct Dial Number: +44 (0) 141 248 9090 Email: [email protected] Contact: Reema Mannah Address: FIRST TITLE INSURANCE plc, Suite 5. 1, Turnberry House, 175 West George Street, Glasgow, G2 2LB Website: www.firsttitleinsurance.eu For further information about First Title or access to our services please contact the appointed NORTHERN IRELAND representatives: Gary Mills Mobile No: +44 (0) 7793814300 Email: [email protected] Derek Young Mobile No: +44 (0) 7763924935 Email: [email protected] Website: www.bluechiptitle.eu First Title Insurance plc. -

Irish News: NEWS: POLITICS: Parents' Plea to Taoiseach for Justice On

Irish News: NEWS: POLITICS: Parents’ plea to taoiseach for justice on son’s murder Friday, 22 February 2008 HOME NEWS SPORT BUSINESS LIVING AN TEOLAS SEARCH SUBSCRIBE LOGIN POLITICS | EDUCATION | COLUMNISTS | LETTERS Most PopularMost Emailed BreakingSportBusinessWorldGossip Issue Changer: NEWS | POLITICS > Parents’ plea to taoiseach for justice on son’s murder By Barry McCaffrey 21/02/08 http://www.irishnews.com/articles/540/542/2008/2/21/580786_337312376797Parents8.html (1 of 5)26/02/2008 13:56:05 Irish News: NEWS: POLITICS: Parents’ plea to taoiseach for justice on son’s murder APPEAL: Twenty years after their son Aidan was shot dead by a British soldier, Elizabeth and John McAnespie are still hoping for information that will help reveal what happened PICTURE: Declan Roughan TAOISEACH Bertie Ahern was last night urged to release a Garda report into the British army killing of an unarmed Co Tyrone GAA fan which has been kept secret for nearly 20 years. It is exactly two decades since 24-year-old Aidan McAnespie was shot dead by a soldier at a permanent border checkpoint at Aughnacloy in 1988. The victim, who had no criminal record and was not a member of any paramilitary organisation, had been walking to a local GAA match when he was shot in the back from an estimated range of 300 metres. The soldier who fired the fatal shot claimed his hands had been wet and had slipped onto the trigger of the heavy sub-machine gun while he had been moving it around the checkpoint’s look-out post. The soldier, whose identity has never been publicised, was fined for negligent discharge of a weapon and given a medical discharge from the army. -

Official Report (Hansard)

Official Report (Hansard) Tuesday 30 September 2014 Volume 97, No 8 Session 2014-2015 Contents Executive Committee Business Legal Aid and Coroners' Courts Bill: Further Consideration Stage .................................................. 1 Private Members' Business Kincora Boys’ Home: Investigation of Allegations of Abuse ............................................................. 11 Oral Answers to Questions Social Development ........................................................................................................................... 19 Agriculture and Rural Development .................................................................................................. 27 Private Members' Business Kincora Boys’ Home: Investigation of Allegations of Abuse (Continued) ......................................... 36 Commonwealth Games: Team NI .................................................................................................... 41 Adjournment Sporting Provision: Dungiven ........................................................................................................... 53 Suggested amendments or corrections will be considered by the Editor. They should be sent to: The Editor of Debates, Room 248, Parliament Buildings, Belfast BT4 3XX. Tel: 028 9052 1135 · e-mail: [email protected] to arrive not later than two weeks after publication of this report. Assembly Members Agnew, Steven (North Down) McAleer, Declan (West Tyrone) Allister, Jim (North Antrim) McCallister, John (South Down) Anderson, -

Ulster Final Programme

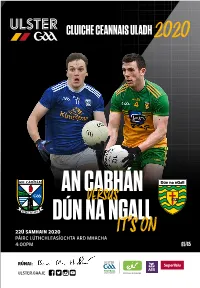

CLUICHE CEANNAIS ULADH2O2O AN CABHÁN DÚN NAVERSUS NGALL 22Ú SAMHAIN 2020 IT’S ON PÁIRC LÚTHCHLEASÍOCHTA ARD MHACHA 4:00PM £5/€5 RÚNAI: ULSTER.GAA.IE The stands may be silent but TODAY’S GAME we know our communities are CLUICHE AN LAE INNIU standing tall behind us. Help us make your SuperFan voice heard by sharing a video of how you Support Where You’re From on: @supervalu_irl @SuperValuIreland using the #SuperValuSuperFans SUPPORT 72 CRAOBH PEILE ULADH2O2O Where You’re From TODAY’S GAME CLUICHE AN LAE INNIU (SUBJECT TO WINNER ON THE DAY) @ ATHLETICVERSUS GROUNDS, ARMAGH SUNDAY 22ND NOVEMBER WATCH LIVE ON Ulster GAA Football Senior Championship Final (4:00pm) Réiteoir: Barry Cassidy (Doire) Réiteoir ar fuaireachas: Ciaran Branagan (An Dún) Maor Líne: Jerome Henry (Maigh Eo) Oifigeach Taobhlíne: Sean Laverty (Aontroim) Maoir: Kevin Toner, Alan Nash, Tom O’Kane & Marty Donnelly CLÁR AN LAE: IF GAME GOES TO EXTRA TIME 15.20 Teamsheets given to Match Referee 1 7. 4 4 Toss & updated Teamsheets to Referee 15.38 An Cabhán amach ar an pháirc 17.45 Start of Extra Time 1st Half 15.41 Dún na nGall amach ar an pháirc 17.56* End of Extra Time 1st Half 15.45 Oifigigh an Chluiche amach ar an pháirc Teams Remain on the Pitch 15.52 Toss 17.58* Start of Extra Time 2nd Half 15.57 A Moment’s Silence 18.00* End of Extra Time 2nd Half 15.58 Amhrán na bhFiann 16.00 Tús an chluiche A water break will take place between IF STILL LEVEL, PHASE 2 (PENALTIES) the 15th & 20th minute of the half** 18:05 Players registered with the 16.38* Leath-am Referee & Toss An Cabhán to leave the field 18:07 Penalties immediately on half time whistle Dún na nGall to leave the field once An Cabhán have cleared the field 16.53* An dara leath A water break will take place between the 15th & 20th minute of the half** 17.35* Críoch an chluiche 38 PRESIDENT’S FOREWORD FOCAL ÓN UACHTARÁN Fearadh na fáilte romhaibh chuig Craobhchomórtas programme. -

The Word “Legend”

True Legends are Gathering in Ballybofey… The word “Legend” is an often overused word in describing great sporting prowess or great GAA games and an official definition states “anyone or anything whose fame promises to be enduring”. The exploits of the youthful Clare Hurling team in winning the Liam McCarthy Cup on Saturday evening last, and in doing so beating a well fancied Cork side managed by the great Jimmy Barry Murphy, are already gaining legendary status. The fact that Cork only managed to lead both games for only 90 seconds is a testament to the Clare team but a word of warning….legends are not made in one sporting year !! The more mature readers will recall the fair haired Pat Spillane from the Templenoe Club in the Kingdom of Kerry, setting off on many a solo run from his own half back line and kicking score after score in All-Ireland Finals…I thought that he ran on the tips of his toes..!!!!…then again Legends can perform true feats of skill. True Legend…11 Munster Medals, 2 National Football Medals, 8 All-Ireland Medals and 9 All-Star Awards. Or Colm O Rourke gracefully weaving around flat-footed corner backs to score goals and points at ease, almost like a giant in slow motion. True Legend. 5 Leinster Medals, 3 National Football Legends, 2 All- Ireland Medals and 3 All-Star Awards. Peter Canavan struck fear into whole football teams when he got the ball within scoring distance and his deft touches when scoring goals would be the pride of any Premiership player on €150k a week. -

County Final 2019 Programme

FÁILTE ÓN CHATHAOIRLEACH give selflessly, for the benefit of the A Chairde Gael, association to which we all belong. I am delighted to welcome you all to our As a county, we have been very fortunate to have so many local showpiece games in the 2019 senior and businesses supporting our teams and competitions. Along with intermediate football championships. the valiant efforts of our much To reach the final of any history books when they hoist the valued Club Derry committee and competition is an achievement in John McLaughlin Cup. members, quite simply, we are itself, but given the current level Today’s games will also be my unable to function. of commitment within our clubs, I last opportunity to attend our It is fitting that two of our most would like to commend the players, championship finals as County experienced and respected officials, coaches, mentors and volunteers, Chairman. I can not over emphasis Barry Cassidy and John Joe Cleary, whose commitment ensures that the enjoyment, pride and delight are taking charge of our showpiece our club championships continue to I have experienced over the past games today. We should remind be so hugely entertaining. 5 years. I would like to thank my ourselves that without our officials, The Mc Feely This year’s championships wife Veronica, and my family, we would not have our games. have provided us all with many for supporting me during my Our association relies heavily moments of drama, excitement, time in post, and also to my club, on the tireless work of our many and brilliance. -

Club Hub Issue #4

N A í n o s D The m ó r o n i á m Clu Inside This p e i M l Edition...... le Hu c ó h r e B The Club AGM i N lé - a Sunday 10th January 2016 M om Venue: Sports Complex h Throw In: 3.00pm or D e t amhn All Support & New Faces han ait Welcome! just a club Reserves League & Championship Winners Coaching Morning & Big Breakfast Dromore U16 Champions www.dromoregfc.com December 2015 | Issue 4 The Club Hub 2015 Review As we reach the end of 2015, Dromore St Dympnas GFC can look back with pride at our achievements over the year and look forward in confidence to more success in the future. As a club, we are very fortunate to have so many loyal supporters who turn out in great numbers to support all our teams from u8 to senior. Our children groups from u8 to u12 participated in blitzes throughout the year with our u10 team winning the shield competition at Killyclogher in September. Our u12 team also won the shield competition in our annual Charles Henry Quinn Tournament in the same month. At youth level our u18 team reached the league final but fell to a strong Moortown team. However pride of place this year must go to our u16 juvenile team who won the Tyrone championship with a great team display against Loughmacrory in the replay at Dunmoyle on the 24th October. There were joyous scenes on the pitch after the game, with numerous family photographs taken which will be cherished for many years into the future. -

An Chomhdháil Bhliantúil 2017 Ostán Hillgrove, Muineachán

An Chomhdháil Bhliantúil 2017 Ostán Hillgrove, Muineachán 1ú Nollaig 2016 ag 7.30i.n Clár 1. Clarú 7.00i.n. (Registrations at 7.00pm) 2. Fáilte – Ostán Hillgrove (Welcome to Hillgrove Hotel) 3. Glacadh na mBun Rialacha (Adoption of Standing Orders) 4. Miontuairiscí an Chomhdháil deiridh (Minutes of Previous Convention 2016) 5. Tuarascáil an Rúnaí Chontae (County Secretary’s Report) 6. Tuarascáil an Chisteoir Chonate (County Treasurer’s Report) 7. Glacadh leis na Cúntaisí eile (Adoption of Sub Committee Reports) 8. Oráid an Chathaoirligh Chontae (County Chairman’s Address) 9. Toghchán na hOifigigh (Election of Officers) 10. Coiste Shláinte agus Folláine – Health & Wellbeing – Cathal Hand 11. Rúin (Motions) 12. Gradaim Bliantúil 2016 (Annual Award Winners 2016) 13. Aon Gnóth Eile (Any other Business) 14. Amhrán na bhFiann (National Anthem) Bun Rialacha – Standing Orders 1. The proposer of a motion may not speak for more than five minutes. 2. A delegate speaking to a motion may not speak for more than three minutes. 3. The proposer of a motion may speak for a second time for three minutes before a vote is taken. 4. No delegate may speak a second time in the debate on the same motion. An Cathaoirelach may consider any matter not on the Clár with the consent of the Majority of the delegates present and voting. 1 Ainmniúcháin - Nominations Cathaoirleach Michéal Mac Mathúna An Bhoth Leas Cathaoirleach Deaglán Ó Flanagáin Craobh Mhairtín Rúnai Áine Ní Fhionnagáin Acadh Na Muileann Proinsias Mac An Bhaird Leachtain Rúnaí Cúnta Eibhlínn Ní Cionnáin -

An Comhchoiste Um Shláinte Agus Leanaí Houses of the Oireachtas

Tithe an Oireachtais An Comhchoiste um Shláinte agus Leanaí Tuarascáil maidir le Deonú Orgán Mean Fomhair 2013 ___________________________ Houses of the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Health and Children Report on Organ Donation September 2013 31/HHCN/013 Foreword by the Chairman of the Joint Committee on Health and Children, Jerry Buttimer TD. The Joint Committee on Health and Children warmly welcomes the Government‟s consultative process regarding its proposal to change the current practice of expressed consent or “opt-in consent” to one of “opt-out consent” in relation to organ donation in Ireland. In June 2012, more than 1,700 Irish adults were receiving haemodialysis, yet throughout all of 2012, just 163 renal transplants were carried out in the Republic of Ireland. To meet the needs of those receiving haemodialysis our health system should be performing in the region of 300 kidney transplants each year. This low rate of organ donation is reflected in Ireland ranking 23rd in European league tables for organ donation. Our current practice of using the “opt-in” system (or expressed consent) is used by only a small minority of countries in the EU. Countries that have changed to “opt-out” systems have seen significant increases in their rates of organ donation. Over a three year period after making the change to opt-out systems, Belgium saw its rate of organ donation increase by 100%, while over the same period, Singapore saw an increase of a massive 700%. Changing to a soft opt-out system has the potential to change public attitudes toward organ donation, and more importantly to vastly increase our rate of organ donation. -

Player Welfare & Injury Prevention

Player Welfare & Injury Prevention: What now? Marty Loughran Physiotherapist Making Headlines • GAA Injuries: The tipping point Conor McCarthy, Irish Examiner January 28th 2012 • 'Rugby players don't know how they do it' Marie Crowe, Sunday Independent January 29th 2012 • “GAA players pushed beyond breaking point." Dr Tadhg MacIntyre, Belfast Telegraph February 9th 2012 • “Rebel rages that Cork GAA left him with €7000 medical bill” Fintan O’Toole, Irish Examiner February 20th 2012 • “Cruciate curse crippling GAA” Irish Examiner February 16th 2012 Still making headlines… • “Knee Injuries top list as GAA shell out €8m in insurance claims” Irish Independent Feb 2014 • “Please stop this abuse” Sunday World Jan 2014 • “Are hip injuries just the price we pay for a stronger, faster, more powerful game” Irish Times Jan 2014 • “Moyna warns of training health risks” Irish independent Jan 2014 Groundhog Day…. • What’s the point? Joe Brolly, Gaelic Life, 11th January 2015 • Paraic Duffy says GAA to tackle fixtures and welfare issues • Saving the GAA Irish Times 28th January 2015 Joe Brolly, Gaelic Life, 19th January 2015 • Its not dark yet, but it’s getting there Eamon Sweeney, Sunday Independent • Enough words, now its time for action 18th January 2015 th Joe Brolly, Gaelic Life, 26 January 2015 • Earley pays price for playing through • Treat the lifeblood with respect pain th Joe Brolly, Gaelic Life, 8th February 2015 Irish News, 19 February 2015 How big is the problem really? • What is the reality? • How has this come about? • What can we do about it? What Percentage of players in a senior inter county squad will get injured each year? 67% Some players get injured more than others 34 players = 40 injuries 1.2 injuries per player per season More likely to get injured during matches or training? Matches 15 times more likely to get injured in matches Bigger the match the more likely you are to get injured 25% of all injuries are recurrent injuries Previous injury is the No. -

OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard)

Committee for Health, Social Services and Public Safety OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard) Organ Donation: Private Member's Bill 23 October 2013 NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY Committee for Health, Social Services and Public Safety Organ Donation: Private Member's Bill 23 October 2013 Members present for all or part of the proceedings: Ms Maeve McLaughlin (Chairperson) Mr Roy Beggs Mr Mickey Brady Ms Pam Brown Mr Gordon Dunne Mr Samuel Gardiner Mr Kieran McCarthy Mr David McIlveen Mr Fearghal McKinney Witnesses: Mrs Dobson MLA - Upper Bann Mr Joe Brolly Dr Aisling Courtney Mr William Johnston Northern Ireland Kidney Patients' Association Mr John Brown Northern Ireland Kidney Research Fund The Chairperson: We have Jo-Anne Dobson MLA, Joe Brolly, Aisling Courtney, William Johnston from the NI Kidney Patients' Association and John Brown from the NI Kidney Research Fund. You are very welcome to the meeting. Please give us a presentation of around 10 minutes, and then we will open the floor to members' comments and questions. Mrs Jo-Anne Dobson (Northern Ireland Assembly): Thank you, Chair, for your kind introduction and the opportunity to present to you today. You will all have your packs with the results of my private Member's Bill consultation on changing the organ donation law to establish a new soft opt-out system. It is certainly a new experience for me to be at this end of the table. I think that it would be helpful, by way of introduction, to go through some of the findings of the consultation. As many of you will know, I have been associated with organ donation charities for over 20 years. -

Interview Report Form

REFERENCE NO. DY/1/7 GAA Oral History Project Interview Report Form Name of Ann-Marie Smith Interviewer Date of Interview 04th Feb 2009 Location Maghera Name of James Molloy and Jim McGuigan Interviewee (Maiden name / (Biographical details available for James only) Nickname) Biographical Summary of Interviewee Gender Male Born Year Born: 1950 Home County: Antrim Education Primary: St Josephs, Dunloy Secondary: Our Lady of Lourdes, Ballymoney Family Siblings: 4 sisters, 1 brother Club(s) Dunloy Cuchullains, Wattie Grahams GAC [Derry] Occupation Shop owner Parents’ Bar owner Occupation Religion Roman Catholic Political Affiliation / N/A Membership Other Club/Society N/A Membership(s) REFERENCE NO. DY/1/7 Date of Report 1st April 2009 Period Covered 1950s – 2009 Counties/Countries Derry, Tyrone Covered Key Themes Travel, Supporting, Grounds, Facilities, Playing, Training, Covered Refereeing, Officials, Administration, Celebrations, Fundraising, Religion, Media, Emigration, Involvement in GAA abroad, Role of the Club in the Community, GAA Abroad, Identity, Rivalries, All-Ireland, Club History, County History, Irish, History, Earliest Memories, Family Involvement, Childhood, Impact on Life, Career, Challenges, Sacrifices, Violence, Politics, Northern Ireland, The Troubles, Opening of Croke Park, Relationship with the Association, Professionalism, Purchase of Grounds, Relationships Interview Summary 00:25 His club is Watty Grahams Maghera, founded in 1948 but with roots going back to 1933 01:10 Jim played minor football and became vice chairman