The Results and Impacts of Egypt's Privatization Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Renews War on the Meat

-- v. SUGAE-- 96 Degree U. S. WEATHER BUREAU, JUNE 4. Last 24 hours rainfall, .00. Test Centrifugals, 3.47c; Per Ton, $69.10. Temperature. Max. 81; Min. 75. Weather, fair. 88 Analysis Beets, 8s; Per Ton, $74.20. ESTABLISHED JULV 2 1656 VOL. XLIIL, NO. 7433- - HONOLULU, HAWAII TERRITORY, TUESDAY, JUNE 5. 1906. PRICE FIVE CENTS. h LOUIS MARKS SCHOOL FUNDS FOSTER COBURN WILL THE ESIDENT SUCCEED BURTON IN KILLED BY RUfl VERY UNITED STATE SENATE RENEWS WAR ON THE AUTO LOW MEAT MEN t - 'is P A Big Winton Machine Less Than Ten Dollars His Message to Congress on the Evils of the , St- .- Over, Crushing Left for Babbitt's 1 Trust Methods Is Turns 4 Accompanied by the -- "1 His Skull. Incidentals, )-- Report of the Commissioner. ' A' - 1 A deplorable automobile accident oc- There are less than ten dollars left jln the stationery and incidental appro- curred about 9:30 last night, in wh'ch ' f. priation for the schol department, rT' Associated Press Cablegrams.) Louis Marks was almost instantly kill- do not know am ' "I what I going to 4-- WASHINGTON, June 5. In his promised message to Congress ed and Charles A. Bon received serious do about it," said Superintendent Bab- (9 yesterday upon the meat trust and its manner of conducting its busi bitt, yesterday. "We pay rents to injury tc his arm. The other occupants the ness, President Kooseveli urged the enactment of a law requiring amount of $1250 a year, at out 1 ! least, stringent inspection of of the machine, Mrs. Marks and Mrs. -

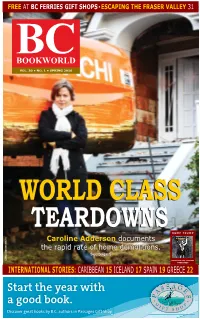

Spring 2016 Volume 30

FREE AT BC FERRIES GIFT SHOPS • ESCAPING THE FRASER VALLEY 31 BC BOOKWORLD VOL. 30 • NO. 1 • SPRING 2016 WORLDWORLD CLASSCLASS TEARDOWNSTEARDOWNS DUMP TRUMP Caroline Adderson documents the rapid rate of home demolitions. See page 5 LAURA SAWCHUK PHOTO PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40010086 INTERNATIONAL STORIES: CARIBBEAN 15 ICELAND 17 SPAIN 19 GREECE 22 Start the year with a good book. Discover great books by B.C. authors in Passages Gift Shop JOIN US May 20th - 22nd, 2016 Prestige Harbourfront Resort Your coaches Salmon Arm, BC and mentors for 2016: A Festival Robert J. Sawyer $3,000 designed by writers Susan Fox IN CASH for writers Ted Bishop Arthur Slade to encourage, support, Joëlle Anthony inspire and inform. Richard Wagamese Bring your muse Victor Anthony and expect to be Michael Slade Jodi McIsaac welcomed, included Alyson Quinn and thoroughly Jodie Renner entertained. Howard White Alan Twigg Bernie Hucul 3 CATEGORIES | 3 CASH PRIZES | ONE DEADLINE FICTION – MAXIMUM 3,000 WORDS CREATIVE NON-FICTION – MAXIMUM 4,000 WORDS on the POETRY – SUITE OF 5 RELATED POEMS Lake DEADLINE FOR ENTRIES: MAY 15, 2016 Writers’ Festival SUBMIT ONLINE: www.subterrain.ca INFO: [email protected] Find out what these published authors and ENTRY FEE: industry professionals can do for you. Register at: $2750 INCLUDES A ONE-YEAR SUBTERRAIN SUBSCRIPTION! www.wordonthelakewritersfestival.com PER ENTRY YOU MAY SUBMIT AS MANY ENTRIES IN AS MANY CATEGORIES AS YOU LIKE “I have attended this conference for Faculty: the past four years. The information is Alice Acheson -

Food Safety Inspection in Egypt Institutional, Operational, and Strategy Report

FOOD SAFETY INSPECTION IN EGYPT INSTITUTIONAL, OPERATIONAL, AND STRATEGY REPORT April 28, 2008 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Cameron Smoak and Rachid Benjelloun in collaboration with the Inspection Working Group. FOOD SAFETY INSPECTION IN EGYPT INSTITUTIONAL, OPERATIONAL, AND STRATEGY REPORT TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE FOR POLICY REFORM II CONTRACT NUMBER: 263-C-00-05-00063-00 BEARINGPOINT, INC. USAID/EGYPT POLICY AND PRIVATE SECTOR OFFICE APRIL 28, 2008 AUTHORS: CAMERON SMOAK RACHID BENJELLOUN INSPECTION WORKING GROUP ABDEL AZIM ABDEL-RAZEK IBRAHIM ROUSHDY RAGHEB HOZAIN HASSAN SHAFIK KAMEL DARWISH AFKAR HUSSAIN DISCLAIMER: The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................................... 1 INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK ......................................................................... 3 Vision 3 Mission ................................................................................................................... 3 Objectives .............................................................................................................. 3 Legal framework..................................................................................................... 3 Functions............................................................................................................... -

Weeks of Killing State Violence, Communal Fighting, and Sectarian Attacks in the Summer of 2013

The Weeks of Killing State Violence, Communal fighting, and Sectarian Attacks in the Summer of 2013 June 2014 Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights 6 Dar Al Shifa (formerly Abdel Latif Bolteya) St., Garden City, Cairo, Telephone & fax: +(202) 27960158 / 27960197 www.eipr.org - [email protected] All printing and publication rights reserved. This report may be redistributed with attribution for non-profit pur- poses under Creative Commons license. www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 Numerous EIPR researchers contributed to this report, but we especially wish to acknowledge those who put themselves at risk to observe events personally, constantly striving to maintain their neutrality amid bloody conflict. We also wish to thank those who gave statements for this report, whether participants in the events, observers or journalists. EIPR also wishes to thank activists and colleagues at other human rights organizations who participated in some joint field missions and/or shared their findings with EIPR. The Weeks of Killing: State Violence, Communal fighting, and Sectarian Attacks in the Summer of 2013 Table of Contents Executive summary .............................................................................................. 5 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 9 Part one: 30 June–5 July: an unprecedented spike in Communal violence 14 30 June: Muqattam .................................................................................... 15 2 July: Bayn -

Couverture BIA 53

Bulletin d'Information Archéologique BIALIII le rêve de Reeves ! Collège de France Institut français Chaire "Civilisation de l'Égypte pharaonique : d'archéologie orientale archéologie, philologie, histoire" Bulletin d'Information Archéologique BIAwww.egyptologues.net LIII Janvier - Juin 2016 Le Caire - Paris 2016 Bulletin d’Information Archéologique REVUE SEMESTRIELLE n° 53 janvier / juin 2016 Directeur de la publication Système de translittération Nicolas GRIMAL des mots arabes [email protected] Rédaction et coordination Emad ADLY [email protected] consonnes voyelles IFAO Ambafrance Caire û و ,î ي ,â ا : q longues ق z ز ‘ ء S/C Valise diplomatique 13, rue Louveau F-92438 Chatillon k brèves : a, i, u ك s س b ب http://www.ifao.egnet.net l diphtongues : aw, ay ل sh ش t ت rue al-Cheikh Ali Youssef ,37 B.P. Qasr al-Aïny 11562 m م s ص th ث .Le Caire – R.A.E Tél. : [20 2] 27 97 16 37 Fax : [20 2] 27 94 46 35 n ن Dh ض G ج Collège de France h autres conventions هـ t ط H ح Chaire "Civilisation de l’Égypte pharaonique : archéologie, (w/û tæ’ marbºta = a, at (état construit و z ظ kh خ "philologie, histoire http://www.egyptologues.net y/î article: al- et l- (même devant les ى ‘ ع D د 52, rue du Cardinal Lemoine “solaires”) F 75231 Paris Cedex 05 غ ذ Tél. : [33 1] 44 27 10 47 Fax : [33 1] 44 27 11 09 Z gh f ف r ر Remarques ou suggestions [email protected] Les articles ou extraits d’articles publiés dans le BIA et les idées qui peuvent s’y exprimer n’engagent que la responsabilité de leurs auteurs et ne représentent pas une position officielle de la Rédaction. -

MES ANNÉES EN ÉGYPTE Avec Photos .Pdf

MES ANNÉES EN ÉGYPTE Notre histoire en Egypte, racontée par Joseph Hakim. Les photos ont été insérées par Elie Lichaa. L’ÉGYPTE ET SES JUIFS QUE J’AI CONNUS. Je suis né à Alexandrie en 1931 - j’ai quitté l’Égypte en Juin 1957 après la guerre de Suez - “Mivtsa’a Kadeche”. Durant cette période et bien avant 1931 les Juifs en Égypte -- ou les Juifs d’Égypte -- passèrent par diverses situations -- bonnes ou mauvaises selon lescirconstances et notamment à la suite de l’idéologie de Hassan -- El-Banna (circa 1925) pour arriver aux pires moments à partir de fin Octobre 56. Hassan El Banna (1906-1949), fondateur des Frères Musulmans Published by the Historical Society of Jews From Egypt. All Rights Reserved Page 1 Plusieurs livres ont été écrits à ce sujet, surtout ceux de Mme Bat-Yaor que je recommande chaleureusement. L’attitude anti-juive s’intensifia davantage vers la fin de la seconde guerre mondiale toujours par l’influence des Frères Musulmans et de Cheikh El-Azhar qui considéraient seuls les Musulmans comme égyptiens de droit! Les Coptes étaient un fait accompli -- à leurs yeux -- une population chrétienne de facto contre laquelle ni les Frères ni El-Azhar n’avaient encore de solution! En même temps que les “Frères” -- des organisations nazies jubilaient avec l’arrivée des Allemands à Al-Alamein aux portes d’Alexandrie -- le Roi Farouk lui-même ne souhaitait pas moins remplacer l’occupation anglaise par celle des hommes d’Adolf Hitler... Roi Farouk (1920-1965) régna du 28.4.1936 au 26.7.1952 La population juive en Égypte d’après les recensements comptait en 1897 25.000 dont 1.000 Cairotes. -

MAREOTIS TH E PTOL EMA IC TOW ERAT AB USIR Photo : Dr

C) MAREOTIS TH E PTOL EMA IC TOW ERAT AB USIR Photo : Dr . Henry M aurer KNOWN AS ARABS' TOW ER MAREOTIS BEING A SHORT ACCOUNT OF THE HISTORY AND ANCIENT MONUMENTS OF THE NORTH-WESTERN DESERT OF EGYPT AND OF LAKE MAREOTIS BY ANTHONY DE COSSON LONDON COUNTRY LIFE LTD. MCMXXXV First Pttblished in I935 ~' iU H TE D IN GR E AT BRITAI N BY MORRIS ON AND GIBB LTD . , LONDON AND EDINBURGH DULCI MEMORIJE NINJE BAIRD ET NOWELLI DE LANCEY FORTH ARABUM GENTIUM STUDIO ET MAREOTIDIS REGIONIS AMORE PARIUM Q.UORUM ALTERAM CALEDONIJE MAGNANIMAM PROLEM ANNO MCMXIX ALTERUM GENEROSUM DE AUSTRALIA MILITEM ANNO MCMXXXIII MORS ADEMIT S. B. R. CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION II II. DAWN BEFORE HISTORY 15 III. MAREOTIS AT THE BEGINNING OF HISTORY 19 IV. THE LIMITS OF THE MARYUT DISTRICT • 24 V. MAREOTIS AS A FRONTIER PROVINCE AND INDEPENDENT EJNGDOM 28 VI. MAREOTIS IN GRiECO-ROMAN TIMES 36 VII. EARLY MONASTIC COMMUNITIES IN MAREOTIS 41 VIII. THE END OF ROMAN DOMINION AND THE ARAB CONQ.UEST 51 IX. THE DECAY OF MAREOTIS 59 X. THE MCIENT INDUSTRIES AND POPULATION 64 XI. LAKE MAREOTIS IN MCIENT TIMES 70 XII. THE LAKE IN LATER TIMES 75 XIII. THE " CANAL" BETWEEN THE LAKE AND THE SEA 83 XIV. THE FLOODING OF 1801-4 AND 1807-8 88 XV. THE CAUSEWAYS OVER THE LAKE 94 XVI. RAINFALL AND MCIENT WATER STORAGE 100 XVII. MCIENT SITES AND PLACES OF INTEREST IN THE MARYUT- ENATON 106 CHERSONESUS PARVA 107 TAENIA 108 SIDI KREIR 108 PLINTHlNE 108 T APOSIRIS MAGNA 109 EL BORDAN ( C H IMO) 115 EL IMAYID 117 KHASHM EL EISH 120 EL QASSABA EL SHARKIYA 122 EL QASSABAT EL GHARBIYA 122 vii viii CONTENTS PAGE XVII. -

Privatization in Egypt .Quarterly Review .April -June 2002

Privatization in Egypt - Quarterly Review April—June 2002 United States, or the Government of Egypt. PRIVATIZATION COORDINATION SUPPORT UNIT Privatization in Egypt Quarterly Review April - June 2002 Provided to the United States Agency for International Development by CARANA Corporation under the USAID Monitoring Services Project Contract # PCE-1-800-97-00014-00, Task Order 800 Unless otherwise stated, opinions expressed in this document are those of the PCSU. They do not necessarily reflect those of USAID, the Government of the CARANA Corporation 20 Aisha El Taymouriya Street, 1st Floor, Suite 2, Garden City, Cairo Tel: (202) 792-5466/5477 Fax: (202) 792-5488 PCSU—Privatization Coordination Support Unit CARANA Corporation WWW.CARANA.COM/PCSU 1 Privatization in Egypt - Quarterly Review April—June 2002 Table of Contents Managing Director’s Note ..........................................................................4 The Privatization and Coordination Support Unit ....................................5 Acknowledgments .....................................................................................6 Special Study: The Result and Impact of Egypt’s Privatization Program .................7 Current Status of Bot and Boot Projects in Egypt .................................14 Ministerial Privatization Activities (Statistical Update) Ministry of Public Enterprise ................................................................15 Ministry of Foreign Trade ....................................................................28 Financial Institution -

Aice-Bs2016edinburgh

Available Online at www.e-iph.co.uk AicE-Bs2016Edinburgh th 7 Asia-Pacific International Conference on Environment-Behaviour Studies, St Leonard Hall, Edinburgh University, United Kingdom, 27-30 July 2016 Heritage Conservation Management in Egypt: The balance between heritage conservation and real-estate development in Alexandria Dina Mamdouh Nassar 1* 1 Architectural Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Alexandria University, Abu Qir St., Ibrahimiya, Alexandria 11432, Egypt Abstract Old cities face many challenges in the search for a better quality of life. They have an obligation towards their past, as they grow and develop. They should not lose their identity or destroy their history. In Egypt, and especially in Alexandria City, the battle between heritage conservation and real estate investment exists and raging. Are we obliged to keep old buildings although they have lost their original settings? The debate of either keeping or demolishing some of the heritage stock to make way for new real estate development is argued in this research at the administrative, public and private levels. This research took into consideration the situation of real estate investments and building laws in Alexandria in the last nine years, since the establishment of the Technical Secretariat of the Standing Committee of the Heritage Conservation Commission in Alexandria. The discussion aims to point out the problems and clarify how to manage heritage buildings in Alexandria and at the same time maintain steady real estate investment. The research also presents a case study on the current building situation in the municipality of San-Stefano, where some heritage buildings are listed while the majority of the area is modernised. -

Alexandria & the Mediterranean Coast

© Lonely Planet Publications 368 Alexandria & the Mediterranean Coast The boundaries of Northern Egypt run smack bang into this dazzling 500km stretch of the Mediterranean seaboard. Here, the fabled city of Alexandria takes its rightful place as the cultural jewel in the coastal crown, while elsewhere the sea’s turquoise waters lap up against pristine but mostly deserted shores. It has been dealt the short straw in life-giving fresh- water, and Egyptian holiday-makers, and a few intrepid travellers, have only recently begun to discover the potential of its untouched beaches. Alexandria wins the unfortunate accolade of being the ‘greatest historical city with the least to show for it’. Once the home of near-mythical historical figures and Wonders of ALEXANDRIA & THE ALEXANDRIA & THE the World, only fragmented memories of Alexandria’s glorious ancient past remain. Today, MEDITERRANEAN COAST MEDITERRANEAN COAST however, the city is too busy gussying up its graceful 19th-century self to lament what’s been and gone. The town shivers at the thought of its own potential: its streets and cafés buzzing with the boundless energy of a new wave of creative youth. Nearby Rosetta is famous for the black-stone key that deciphered hieroglyphics and was unearthed here – though this Nile-side port once rivalled Alexandria during that town’s more woeful days. Halfway across the coast to Libya, the memorials of El Alamein loom as solemn reminders of the lives lost during the North Africa campaigns of WWII. Meanwhile, not far off, a battalion of resorts offers a white-sand beach distraction from too much war-time reflection. -

Egypt Country Handbook 1

Egypt Country Handbook 1. This handbook provides basic reference information on Egypt, including its geography, history, government, military forces, and communications and transportation networks. This information is intended to familiarize military personnel with local customs and area knowledge to assist them during their assignment to Egypt. 2. This product is published under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Defense Intelligence Production Program (DoDIPP) with the Marine Corps Intelligence Activity designated as the community coordinator for the Country Handbook Program. This product reflects the coordinated U.S. Defense Intelligence Community position on Egypt. 3. Dissemination and use of this publication is restricted to official military and government personnel from the United States of America, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, NATO member countries, and other countries as required and designated for support of coalition operations. 4. The photos and text reproduced herein have been extracted solely for research, comment, and information reporting, and are intended for fair use by designated personnel in their official duties, including local reproduction for training. Further dissemination of copyrighted material contained in this document, to include excerpts and graphics, is strictly prohibited under Title 17, U.S. Code. Contents KEY FACTS . 1 U.S. MISSION . 3 U.S. Embassy . 3 U.S. Diplomatic Representatives . 3 USIS Offices . 3 Travel Advisories . 5 Entry Requirements . 5 Immunization Requirements . 6 Customs Restrictions . 6 GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE . 7 Geography . 7 Major Cities . 7 Boundaries . 14 Maritime Claims . 14 Border Disputes . 14 Topography . 15 Irrigation . 16 Deserts . 17 Climate . 19 Environment . 21 TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATION . 22 Transportation . 22 Roads . 24 Rail . -

Er Begins Talks with Syrians

PAGE THIRTY-SIX - MANCHESTER EVENING HERALD. Manchester. Conn., Thurs., May 2. 1974 o MANCHESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, MAY 3, 1974- VOL. XCIH, No. 182 Manchester^A City of Village Charm Therels womens denim clog TWENTY-FOUR PAGES N Wedge heel, rope wrap, and a fringed aT agim and frayed crossover strap that just won't unravel. er Begins R I) 6 J R 7 * 1 CAB shoe tor R' A S H s T f V e s A M 0 C 0 7 /0 « a )« 5r everything Talks With Syrians DAMASCUS (UPI) - conversation in Tel Aviv with Israel has said there must be police .patrolled Damascus for Secretary of State Henry A. Prime Miinister Golda Meir a cease-fire on the Golan the Kissinger visit. you 00. Kissinger brought his shuttle before flying here for his talks Heights before there can be diplomacy to Damascus today with President Hafez Assad. “meaningful negotiations” on a On Wednesday sections of the Blue denim. It’s everybody’s to seek an end to the Israeli- “We seek security and pehce troop disengagement program. crowd in a 200,000-strong May Syrian fighting on the Golan and not the imposition of views Syria, backed by Soviet arms Day pprade of rifle-carrying fun-time favorite. And Tag way has Heights but ran into a Syrian the “blues” In sneakers, of any party on any other par and money, has rejected dis students shouted slogans hostile your choice pledge to continue the battle un ty,” Kissinger said after the engagement until Israel gives to Kissinger and his mission, Roger Landon, a handicapped person, demonstrates his ability to operate his own business sandals and sllp-ohs for til every inch of Syrian meeting with Mrs.