Chapter 5 Teacher's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Satyricon of Petronius Arbiter

Satyricon of Petronius Arbiter Translated by Firebaugh Satyricon of Petronius Arbiter Table of Contents Satyricon of Petronius Arbiter..........................................................................................................................1 Translated by Firebaugh..........................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................................5 I................................................................................................................................................................6 II THE AUTHOR....................................................................................................................................6 III REALISM...........................................................................................................................................8 IV FORGERIES OF PETRONIUS.........................................................................................................9 VOLUME 1.ADVENTURES OF ENCOLPIUS AND HIS COMPANIONS................................................11 CHAPTER THE FIRST.........................................................................................................................11 CHAPTER THE SECOND...................................................................................................................12 CHAPTER THE THIRD.......................................................................................................................12 -

Journal of Roman Archaeology

JOURNAL OF ROMAN ARCHAEOLOGY VOLUME 26 2013 * * REVIEW ARTICLES AND LONG REVIEWS AND BOOKS RECEIVED AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL Table of contents of fascicule 2 Reviews V. Kozlovskaya Pontic Studies 101 473 G. Bradley An unexpected and original approach to early Rome 478 V. Jolivet Villas? Romaines? Républicaines? 482 M. Lawall Towards a new social and economic history of the Hellenistic world 488 S. L. Dyson Questions about influence on Roman urbanism in the Middle Republic 498 R. Ling Hellenistic paintings in Italy and Sicily 500 L. A. Mazurek Reconsidering the role of Egyptianizing material culture 503 in Hellenistic and Roman Greece S. G. Bernard Politics and public construction in Republican Rome 513 D. Booms A group of villas around Tivoli, with questions about otium 519 and Republican construction techniques C. J. Smith The Latium of Athanasius Kircher 525 M. A. Tomei Note su Palatium di Filippo Coarelli 526 F. Sear A new monograph on the Theatre of Pompey 539 E. M. Steinby Necropoli vaticane — revisioni e novità 543 J. E. Packer The Atlante: Roma antica revealed 553 E. Papi Roma magna taberna: economia della produzione e distribuzione nell’Urbe 561 C. F. Noreña The socio-spatial embeddedness of Roman law 565 D. Nonnis & C. Pavolini Epigrafi in contesto: il caso di Ostia 575 C. Pavolini Porto e il suo territorio 589 S. J. R. Ellis The shops and workshops of Herculaneum 601 A. Wallace-Hadrill Trying to define and identify the Roman “middle classes” 605 T. A. J. McGinn Sorting out prostitution in Pompeii: the material remains, 610 terminology and the legal sources Y. -

The Shops and Shopkeepers of Ancient Rome

CHARM 2015 Proceedings Marketing an Urban Identity: The Shops and Shopkeepers of Ancient Rome 135 Rhodora G. Vennarucci Lecturer of Classics, Department of World Languages, Literatures, and Cultures, University of Arkansas, U.S.A. Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to explore the development of fixed-point retailing in the city of ancient Rome between the 2nd c BCE and the 2nd/3rd c CE. Changes in the socio-economic environment during the 2nd c BCE caused the structure of Rome’s urban retail system to shift from one chiefly reliant on temporary markets and fairs to one typified by permanent shops. As shops came to dominate the architectural experience of Rome’s streetscapes, shopkeepers took advantage of the increased visibility by focusing their marketing strategies on their shop designs. Through this process, the shopkeeper and his shop actively contributed to urban placemaking and the distribution of an urban identity at Rome. Design/methodology/approach – This paper employs an interdisciplinary approach in its analysis, combining textual, archaeological, and art historical materials with comparative history and modern marketing theory. Research limitation/implications – Retailing in ancient Rome remains a neglected area of study on account of the traditional view among economic historians that the retail trades of pre-industrial societies were primitive and unsophisticated. This paper challenges traditional models of marketing history by establishing the shop as both the dominant method of urban distribution and the chief means for advertising at Rome. Keywords – Ancient Rome, Ostia, Shop Design, Advertising, Retail Change, Urban Identity Paper Type – Research Paper Introduction The permanent Roman shop was a locus for both commercial and social exchanges, and the shopkeeper acted as the mediator of these exchanges. -

Romans Had So Many Gods

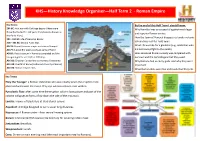

KHS—History Knowledge Organiser—Half Term 2 - Roman Empire Key Dates: By the end of this Half Term I should know: 264 BC: First war with Carthage begins (There were Why Hannibal was so successful against much lager three that lasted for 118 years; they become known as and superior Roman armies. the Punic Wars). How the town of Pompeii disappeared under volcanic 254 - 191 BC: Life of Hannibal Barker. ash and was lost for 1500 years. 218—201 BC: Second Punic War. AD 79: Mount Vesuvius erupts and covers Pompeii. What life was like for a gladiator (e.g. celebrities who AD 79: A great fire wipes out huge parts of Rome. did not always fight to the death). AD 80: The colosseum in Rome is completed and the How advanced Roman society was compared with inaugural games are held for 100 days. our own and the technologies that they used. AD 312: Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity. Why Romans had so many gods. And why they were AD 410: The fall of Rome (Goths sack the city of Rome). important. AD 476: Roman empire ends. What Roman diets were like and foods that they ate. Key Terms Pliny the Younger: a Roman statesman who was nearby when the eruption took place and witnessed the event. Only eye witness account ever written. Pyroclastic flow: after some time the eruption column loses power and part of the column collapses to form a flow down the side of the mountain. Lanista: Trainer of Gladiators at Gladiatorial school. Aqueduct: A bridge designed to carry water long distances. -

I MUST SEE ROMA... 2021 Pozzuoli, Pompei, Foro Apoio, Tre Taberna, Farscati, Roma

I MUST SEE ROMA... 2021 Pozzuoli, Pompei, Foro Apoio, Tre Taberna, Farscati, Roma Day 1 Arrival / Petuoli city through the northern gates, to continue his journey towards Rome. Upon arrival at Rome International Airport, we will meet our professional We will walk approx 3 miles along one of the best preserved parts of the tour escort and travel south on the “Sun Highway” , to reach Pozzuoli Appian Way. This part of the paved Roman way is easily walkable and it in approx. 3 hrs time. We are exactly in the same location where Paul is really amazingwith its fantastic landscape, a well preserved bidge of landed. “... and after one day the south wind blew, and we came the next the XVI century that goes beyond the small river and several other rests of day to Puteoli.” (Acts 28,13) Some time at leisure to relax at hotel, before ancient monuments. Overnight in Foro Appio, at “Mansio Hotel” which is moving to the centre of the village to visit the area of the seaport and the located in the same place where an ancient Roman “posta” . The Appian Roman Amphitheater in order to get a sense of what Paul experienced Way had rest stations all along its path, in which travelers could stay and once he arrived on the mainland of the “Roman Empire”. Take a break to get a shelter for the night, have a warm meal and let the horses recover. taste a real Napolitano coffee and a “sfogliatella” before returning to our Forum Appii (Foro Appio) is the only historical certified destinations in hotel for dinner and overnight (D) Latium of Paul’s journey to Rome. -

Archaeology and Economy in the Ancient World, Bd. 42: Shops

Commerce and Architecture in Late Hellenistic Italy: the Emergence of the Taberna Row Miko Flohr One recent development in the study of Roman crafts and retail is that there seems to be a slight shift away from studying the actual work installations towards studying the architectural environments within which these were situated.1 This development seems to offer a number of opportunities. One of these is that, while comparative approaches to actual work installations or retail practices are often highly complex if not impossible, the study of the architectural and spatial contexts in which they were situated makes it considerably more straightforward for scholars working in varying geographical and chronological contexts to actually confront each other’s observations. Moreover, an increasing focus on the place of work in the built environment also makes it easier to engage in debates with scholars working on other topics: more than anything else it is architecture that connects the study of crafts and retail to broader debates about Roman urban communities. It needs no arguing that this is important: not only were there many people spending their working days in shops and workshops, in many places, these people also were, in a physical way, very central to the urban communities, in which they lived, and could be a defining part of the urban atmosphere – particularly in Roman Italy, but to some extent also elsewhere in the Roman world. This article aims to push the role of architecture in debates about urban crafts and retail a little bit further, and brings up the issue of how these architectural contexts changed over time, and how this is to be understood economically. -

The Ears of Hermes

The Ears of Hermes The Ears of Hermes Communication, Images, and Identity in the Classical World Maurizio Bettini Translated by William Michael Short THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRess • COLUMBUS Copyright © 2000 Giulio Einaudi editore S.p.A. All rights reserved. English translation published 2011 by The Ohio State University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bettini, Maurizio. [Le orecchie di Hermes. English.] The ears of Hermes : communication, images, and identity in the classical world / Maurizio Bettini ; translated by William Michael Short. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1170-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1170-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9271-6 (cd-rom) 1. Classical literature—History and criticism. 2. Literature and anthropology—Greece. 3. Literature and anthropology—Rome. 4. Hermes (Greek deity) in literature. I. Short, William Michael, 1977– II. Title. PA3009.B4813 2011 937—dc23 2011015908 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1170-0) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9271-6) Cover design by AuthorSupport.com Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Garamond Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American Na- tional Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Translator’s Preface vii Author’s Preface and Acknowledgments xi Part 1. Mythology Chapter 1 Hermes’ Ears: Places and Symbols of Communication in Ancient Culture 3 Chapter 2 Brutus the Fool 40 Part 2. -

Greeks and Romans.Mlc

DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS GREEKS AND ROMANS Courses and Programs Offered at the University of Virginia Spring 2020 2 3 THE GREEKS AND ROMANS at the University of Virginia SPRING, 2020 Each semester the faculty of the Department of Classics and their colleagues in other departments offer a rich program of courses and special events in classical studies. The Greeks and Romans is published to inform the University community of the wealth of opportunities for study during the spring semester, 2020. These are described in the next pages under the following headings: I. CLASSICS: Classics courses in translation. II. GREEKS: Courses in Greek language and literature, and in Greek art, ideas, history, and other aspects of Greek civilization. III. ROMANS: Courses in the Latin language and Roman literature, and in Roman art, ideas, history, and other aspects of Roman civilization. IV. AFFILIATED: Courses presenting Classical studies in relation to other subjects. V. SPECIAL PROGRAMS AND EVENTS ****************************************** 4 I. CLASSICS CLAS 2020 ROMAN CIVILIZATION Mr. Hays <bgh2n> TR 1230-1345 Discussion F 1000-1050 F 1100-1150 F 1400-1450 F 1500-1550 This course serves as a general introduction to the history, literature, social life, institutions, and ideology of ancient Rome, from the origins to the 2nd century AD. We will look especially at the ways in which the Romans constructed a collective cultural identity for themselves, with attention paid also to groups marginal to or excluded from that identity (e.g. women, slaves, barbarians). Readings will focus on the ancient texts and sources, including the comedies of Plautus and Terence, Vergil’s epic Aeneid, historical writing by Sallust and Tacitus, biographies by Plutarch and Suetonius, the love poetry of Ovid, and Petronius’s novel Satyrica. -

The Mini-Columbarium in Carthage's Yasmina

THE MINI-COLUMBARIUM IN CARTHAGE’S YASMINA CEMETERY by CAITLIN CHIEN CLERKIN (Under the Direction of N. J. Norman) ABSTRACT The Mini-Columbarium in Carthage’s Roman-era Yasmina cemetery combines regional construction methods with a Roman architectural form to express the privileged status of its wealthy interred; this combination deploys monumental architectural language on a small scale. This late second or early third century C.E. tomb uses the very North African method of vaulting tubes, in development in this period, for an aggrandizing vaulted ceiling in a collective tomb type derived from the environs of Rome, the columbarium. The use of the columbarium type signals its patrons’ engagement with Roman mortuary trends—and so, with culture of the center of imperial power— to a viewer and imparts a sense of group membership to both interred and visitor. The type also, characteristically, provides an interior space for funerary ritual and commemoration, which both sets the Mini-Columbarium apart at Yasmina and facilitates normative Roman North African funerary ritual practice, albeit in a communal context. INDEX WORDS: Funerary monument(s), Funerary architecture, Mortuary architecture, Construction, Vaulting, Vaulting tubes, Funerary ritual, Funerary commemoration, Carthage, Roman, Roman North Africa, North Africa, Columbarium, Collective burial, Social identity. THE MINI-COLUMBARIUM IN CARTHAGE’S YASMINA CEMETERY by CAITLIN CHIEN CLERKIN A.B., Bowdoin College, 2011 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2013 © 2013 Caitlin Chien Clerkin All Rights Reserved. THE MINI-COLUMBARIUM IN CARTHAGE’S YASMINA CEMETERY by CAITLIN CHIEN CLERKIN Major Professor: Naomi J. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Charles H. Cosgrove Professor of Early

CURRICULUM VITAE Charles H. Cosgrove Professor of Early Christian Literature and Director of Ph.D. Program Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary 2121 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL 60201 [email protected] 847–866–3880 EDUCATIONAL HISTORY Ph.D. 1985 Princeton Theological Seminary Princeton, NJ M.Div. 1979 Bethel Theological Seminary St. Paul, MN B.A. 1976 Bethel College, St. Paul, MN Further Study 1995-97 Chicago-Kent College of Law Chicago, IL 1988 Instituto Superior Evangélico de Estúdios Teológicos (ISEDET) Buenos Aires, Argentina 1982-84 University of Tübingen, (then West) Germany PUBLICATIONS BOOKS An Ancient Christian Hymn with Musical Notation: Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1786: Text and Commentary. STAC 65; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011. 1 In Other Words: Incarnational Translation for Preaching. With W. Dow Edgerton. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2007. Cross-Cultural Paul: Journeys to Others, Journeys to Ourselves. With Herold Weiss and K. K. Yeo. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2005. The Meanings We Choose: Hermeneutical Ethics, Indeterminacy and the Conflict of Interpretations. Editor and contributor. London and New York: T. & T. Clark International (Continuum), 2004. Appealing to Scripture in Moral Debate: Five Hermeneutical Rules. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2002. Elusive Israel: The Puzzle of Election in Romans. Nashville: Westminster John Knox, 1997. Church Conflict: The Hidden Systems Behind the Fights. Co-author with Dennis D. Hatfield. Nashville: Abingdon, 1994. Faith and History: Essays in Honor of Paul W. Meyer. Co-editor with John T. Carroll and E. Elizabeth Johnson. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1990 (including the Introduction and a contributing essay). The Cross and the Spirit: A Study in the Argument and Theology of Galatians. -

Latin Curriculum Standards. Revised. INSTITUTION Delaware State Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 333 717 FL 019 201 TITLE Latin Curriculum Standards. Revised. INSTITUTION Delaware State Dept. of Public Instruction, Dover. PUB DATE Nov 90 NOTE 50p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) -- Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Behavioral Objectives; Cultural Awareness; Cultural Education; *Curriculum Design; Educational Objectives; Elementary Secondary Education; FLES; Grammar; *Latin; Oral Language; Peading Skills; Second Language Instruction; *Second Language Programs; *State Standards; Statewide Planning; Writing Skills IDENTIFIERS *Delaware ABSTRACT Delaware's state standards for the Latin curriculum in the public schools are presented. An introductory section outlines the goals of Latin program for reading, cultural awareness, grammar, writiny, and oral language and briefly discusses the philosophy of and approaches to Latin instruction in elementary and middle schools. Three subsequent sections outline fundamental grammatical concepts and present specific behavioral objectives for a variety of topic areas at each of three instructional levels, including levels: I (grades 4-6, 7-8, 9, 10, 11, and 12); II(grades 7-8, 9, 10, 11, and 12); and III-IV (grades 9, 10, 11, and 12). Topic areas include the following: the world of the ancient Romans; greetings and leave-taking; classroom communication; mythology and legend; famous Romans and legendary history; Roman names; the Roman family and home; Roman food and dress; everyday life; our Latin linguistic and artistic heritage; politics and history; Roman holidays; Roman social structure; Caesar's commentaries and other Latin readings; and Roman oratory, comedy, and poetry. A 17-item bibliography is included. (MSE) 1*********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. -

Why Did Clodius Shut the Shops? the Rhetoric of Mobilizing a Crowd in the Late Republic*

Historia 65, 2016/2, 186–210 Amy Russell Why did Clodius shut the shops? The rhetoric of mobilizing a crowd in the Late Republic* Abstract: When Publius Clodius ordered Rome’s tabernae to be shut for one of his meetings in 58 B C, he was not only trying to gather a crowd by forcing tabernarii onto the street. Shutting the shops was a symbolic move alluding to the archaic iustitium and to the actions of Tiberius Grac- chus. It allowed Clodius to claim both that his meeting was vital to the safety of the res publica and that he (and not Cicero) had the support of the entire Roman people, including the lowliest. Keywords: Roman political history – Clodius – Cicero – rhetoric – iustitium – tabernae Publius Clodius is almost universally acknowledged as an innovator who found new and better ways of taking advantage of the tribunate of the plebs as a position of pow- er.1 One conventional understanding of his achievement is that he was the first man who successfully made direct appeal to Rome’s urban plebs as his constituency.2 The contio was not the only form of political activity in Rome, but it was one of the most important, and the one in which Clodius excelled. Contional politics was a numbers game: politicians cowed their opponents by demonstrating the size of the crowd they could gather.3 A particularly large, fervent, or well-deployed group could even bar op- ponents physically from the space of politics.4 Clodius used personal charisma to draw a crowd, and appealed to a broad base by breaking free from what remained of an aristocratic consensus to propose boldly populist measures.5 It is often claimed that * Some of the following material derives from papers given at Durham in 2012, and at the APA annual meeting in Seattle and the Norman Baynes meeting in Stevenage in 2013.