Contents Feminisms & Activisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Verarbeitung Emotionaler Objekte Bei Borderline-Patientinnen: Eine Untersuchung Mit Ereigniskorrelierten Potentialen (EKP)

Klinik für Psychatrie und Psychotherapie III Universitätsklinikum Ulm Prof. Dr. Dr. Manfred Spitzer Ärztlicher Direktor Die Verarbeitung emotionaler Objekte bei Borderline-Patientinnen: Eine Untersuchung mit ereigniskorrelierten Potentialen (EKP) Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Medizin der Medizinischen Fakultät der Universität Ulm von Ute Neff Bad Saulgau 2018 Amtierender Dekan: Prof. Thomas Wirth 1. Berichterstatter: Prof. Carlos Schönfeld-Lecuona 2. Berichterstatter: Prof. Christiane Waller Tag der Promotion: 16. November 2018 Teile dieser Dissertation wurden bereits im folgenden Fachartikel veröffentlicht: Kiefer M, Neff U, Schmid MM, Spitzer M, Connemann BJ, Schönfeld-Lecuona C: Brain activity to transitional objects in patients with borderline personality disorder. Scientific Reports 7(1):13121 (2017) Inhaltsverzeichnis AbkürzungsverzeichnisVI 1 Einleitung1 1.1 Borderline-Persönlichkeitsstörung . .1 1.2 Bindungsverhalten . .7 1.2.1 Bindungstheorie . .7 1.2.2 Bindungsverhalten bei Borderline-Persönlichkeitsstörung . 10 1.3 Transitionale und emotionale Objekte . 12 1.3.1 Das transitionale Objekt . 12 1.3.2 Emotionale Objekte bei Erwachsenen . 13 1.3.3 Borderline-Patienten und emotionale Objekte . 14 1.4 Grundlagen der Elektroenzephalographie und ereigniskorrelierter Potentiale 15 1.5 EKP auf emotionale Objekte . 19 1.6 Ziel der Studie . 20 1.7 Hypothesen . 21 2 Material und Methoden 23 2.1 Stichprobenbeschreibung . 23 2.1.1 Probanden . 23 2.1.2 Ein- und Ausschlusskriterien . 24 2.1.3 Fragebögen zur Erfassung der Psychopathologie . 26 2.2 Stimuli . 30 2.3 Experiment zur Erkennung emotionaler Objekte . 31 2.4 Allgemeiner Ablauf der Studie . 34 2.5 EEG-Aufzeichnung und EKP-Analyse . 34 IV Inhaltsverzeichnis 2.6 Statistische Analyse . 36 3 Ergebnisse 40 3.1 Bewertung der Stofftiere . -

SEPTEMBER 2004 Any Persons Living Or Dead Is Coincidental

THE h o t t i e OF THE LINING BIRDCAGES SINCE 1997 FRENCH ISSUE month EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Todd Nienkerk olores MANAGING EDITOR Kristin Hillery DESIGN DIRECTOR JJ Hermes Gifter of Bibles ASSOCIATE Elizabeth Barksdale EDITORS Ryan B. Martinez D WRITING STAFF Kathryn Edwards Who is this hot Magdalenian mama beckoning me to her Bradley Jackson Fertile Crescent? Your lips, swollen with Passion, coax me into Chanice Jan Todd Mein the sizzling sinlessness of scripture. Did you spill some Holy John Roper Joel Siegel Water on your lap, or are you just anticipating the Rapture? Christie Young Press me against your virginal bosom so I can be DESIGN STAFF David Strauss born again, and again — and again! Christina Vara ADVERTISING Emily Coalson vital stats PUBLICITY Stan Babbitt Hobbies: Accepting missionary positions, being an open book, shopping at the Dress Barn, DISTRIBUTION Stephanie Bates “Bible”-beating, being on her knees WEBMASTER Mike Kantor ADMINISTRATIVE Erica Grundish Turn-ons: submission, “Dogma,” destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, Abel SUPERVISOR Turn-offs: Getting off the high horse, abridging, “The DaVinci Code”, polytheism, birth ADMINISTRATIVE Leala Ansari control, Cain, lap dances, Darwin, the Pope-mobile ASSISTANTS Doug Cooper Jef Greilich Sara Kanewske meeting at busy intersections to play right-of-way • People running to class look funny and deserve to Lindsay Meeks games with speeding vehicles. be laughed at. Jill Morris Garrett Rowe • Overeager returning students will continue to • The 40 Acres Buses will be renamed “40- Toby Salinger like school enough for the both of you. Thousand Acres.” If they weren’t traveling 40,000 Ari Schulman around • Captain Clueless will attempt to charm you by acres, why else would they take so goddamn long Laura Schulman turning courteous small talk into a biographical and travel caravan-style? Eric Seufert discourse about himself. -

The DIY Careers of Techno and Drum 'N' Bass Djs in Vienna

Cross-Dressing to Backbeats: The Status of the Electroclash Producer and the Politics of Electronic Music Feature Article David Madden Concordia University (Canada) Abstract Addressing the international emergence of electroclash at the turn of the millenium, this article investigates the distinct character of the genre and its related production practices, both in and out of the studio. Electroclash combines the extended pulsing sections of techno, house and other dance musics with the trashier energy of rock and new wave. The genre signals an attempt to reinvigorate dance music with a sense of sexuality, personality and irony. Electroclash also emphasizes, rather than hides, the European, trashy elements of electronic dance music. The coming together of rock and electro is examined vis-à-vis the ongoing changing sociality of music production/ distribution and the changing role of the producer. Numerous women, whether as solo producers, or in the context of collaborative groups, significantly contributed to shaping the aesthetics and production practices of electroclash, an anomaly in the history of popular music and electronic music, where the role of the producer has typically been associated with men. These changes are discussed in relation to the way electroclash producers Peaches, Le Tigre, Chicks on Speed, and Miss Kittin and the Hacker often used a hybrid approach to production that involves the integration of new(er) technologies, such as laptops containing various audio production softwares with older, inexpensive keyboards, microphones, samplers and drum machines to achieve the ironic backbeat laden hybrid electro-rock sound. Keywords: electroclash; music producers; studio production; gender; electro; electronic dance music Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 4(2): 27–47 ISSN 1947-5403 ©2011 Dancecult http://dj.dancecult.net DOI: 10.12801/1947-5403.2012.04.02.02 28 Dancecult 4(2) David Madden is a PhD Candidate (A.B.D.) in Communications at Concordia University (Montreal, QC). -

The Teaches of Peaches: Rethinking the Sex Hierarchy and the Limits of Gender

MA MAJOR RESEARCH PAPER The Teaches of Peaches: Rethinking the Sex Hierarchy and the Limits of Gender Discourse by Christina Bonner Supervised by Dr. Jennifer Brayton The Major Research Paper is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Joint Graduate Program in Communication & Culture Ryerson University -- York University Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2010 © Christina Bonner 2010 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this research paper. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this research paper to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. 7 / ChristinaLBonner I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this research paper by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. EMlstma Honner ii The Teaches of Peaches: Rethinking the Sex Hierarchy and the Limits of Gender Discourse Christina Bonner Master of Arts, Program in Communication and Culture Ryerson and York University 2010 Abstract: The goal of this Major Research paper is an exploration detailing how Canadian Electro-Pop artist Peaches Nisker transcends nonnative gender and sex politics through perfonnance and frames the female erotic experience in a way that not only disempowers heterosexuality but also provides a broader more inclusive sexual politics. Through this analysis I focus specifically on three distinct spheres; perfonnance, fandom and use of technology to argue that her critique of sexual conventions provides an cxpansive and transgressive new defmition of female sexuality. Musical perfonnances by female artists, particularly icons such as Madonna and Britney Spears, have demonstrated popular culture's inability to legitimize quecr and non compulsory heterosexual practices. -

Interculturalism, Intermediality and the Trope of Testimony

“Alla människor har sin berättelse”: Interculturalism, Intermediality and the Trope of Testimony in Novels by Ekman, Ørstavik and Petersen By Suzanne Brook Martin A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Linda Rugg, Chair Professor John Lindow Professor Hertha D. Sweet Wong Professor Troy Storfjell Fall 2010 Abstract “Alla människor har sin berättelse”: Interculturalism, Intermediality and the Trope of Testimony in Novels by Ekman, Ørstavik and Petersen by Suzanne Brook Martin Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Rugg, Chair This study focuses on Kerstin Ekman’s Vargskinnet trilogy (1999-2003), Hanne Ørstavik’s Presten (2004) and Martin Petersen’s Indtoget i Kautokeino (2004). The premise of this dissertation is that these novels provide a basis for investigating a subcategory of witness literature called witness fiction, which employs topoi of witness literature within a framework of explicitly fictional writing. Witness literature of all types relies on the experience of trauma by an individual or group. This project investigates the trauma of oppression of an indigenous group, the Sami, as represented in fiction by members of majority cultures that are implicated in that oppression. The characters through which the oppressed position is reflected are borderline figures dealing with the social and political effects of cultural difference, and the texts approach witnessing with varying degrees of self-awareness in terms of the complicated questions of ethics of representation. The trauma that is evident in my chosen texts stems from interactions between Sami and non-Sami communities, and I discuss the portrayal of interculturalism within these texts. -

HOT MESS 2Nd Draft.Fdr

HOT MESS by Jenni Ross Based on the novel, "THE HEARTBREAKERS" By Pamela Wells Second Draft 12/16/09 Goldsmith-Thomas Productions 239 Central Park West, Suite 6A New York, NY 10024 (212) 243-4147 OVER BLACK WE HEAR THE INTRO TO “LITTLE GREEN BAG” BY THE GEORGE BAKER SELECTION (ICONIC INTRODUCTION TO RESERVOIR DOGS). COLD OPEN: EXT. ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PLAYGROUND - DAY/FLASHBACK Four, eleven year old girls, strut confidently across the playground wearing sunglasses, a’la Reservoir Dogs. Other kids move out of their way. BEGIN TITLE SEQUENCE OVER MONTAGE: The four girls come to the aid of another kid being bullied by an older boy on the playground; they TP someone’s house by the light of the moon, laughing uncontrollably; they throw their hands high in the air on a roller coaster, screaming; they start a food fight in the cafeteria and are hauled into detention; the girls play kickball and kick ass. Kelly tags a boy with the ball as she slides onto the base. ALEXIA (V.O.) Welcome to my halcyon days. A simpler time when math homework didn’t require a calculator and your underwear still covered your ass. They raise their hands in class, unashamed that they know the answer. ALEXIA (V.O.) (CONT’D) Back then my friends and I were on top of the pre-pubescent world. We were happy to be ourselves and no amount of Britney Spears videos or American Apparel ads could convince us otherwise. The girls walk by a large print ad for Guess Jeans - Raven zips back into the shot and defaces the model by “crossing her eyes” with a Sharpie. -

Supreme Being LOS ANGELES 11.09.14

SCENE & HERD Supreme Being LOS ANGELES 11.09.14 Left: Jack Black with artist Steven Hull. Right: Steven Hull's Circus of Death installation. (Photos: Miriam Katz) “FUCK THIS VIP SHIT—I want some real California dick!” cried a braless Bridget Everett as she made her way toward the general admission section of the crowd. Everett eventually found an object for her affection, a masked dandy she nicknamed “Corky” (cause he was “Down’s-y in the eyes”), whom she cajoled into playing a grown-up game of airplane, bearing the weight of her significant frame right there in the middle of the stage. Soon enough she was motorboating Peaches (the musician, not the fruit), forcing a security guard’s head up her dress, and crooning gorgeously about lady parts of various shapes and sizes. The sun was still shining, but she was working on her night moves. FOMO abounded among the ten thousand attendees at the second annual Festival Supreme, a ten-hour comedy, music, and visual art event organized by Jack Black and Kyle Gass of Tenacious D. Many sported elaborate costumes as we navigated the fifty-plus live acts across four stages, as well as a fifty four-thousand-square-foot art installation, all in an early-twentieth-century Shriners temple located in downtown Los Angeles. The lineup was sick (Fred Armisen, Margaret Cho, Nick Kroll, to name a few), and as if that weren’t enough, special, surprise guests included Weird Al Yankovic, who shredded the Keytar with Tenacious D, and Zach Galifianakis, who starred, along with Orange Is the New Black’s Lauren Lapkus and Parks and Recreation’s Adam Scott, in a live rendition of Scott Aukerman’s podcast and IFC show Comedy Bang! Bang! The heart of the festival lay in its focus on comedy music, a seemingly puerile medium with surprisingly lofty potential. -

How Urban Farming Initiatives Are Changing the Policy Regime in Amsterdam

Ticket to paradise or how I learned to stop worrying and love the transition: How urban farming initiatives are changing the policy regime in Amsterdam Research design Name: John-Luca de Vries Studentnumber: 10762779 Datum: July 6th, 2018 Word count: 15821 Supervisors: John Grin & Anna Aalten Introduction The stability of urban food systems depends on a properly functioning global market, open trade routes, affordable energy and stable weather conditions, factors which will likely become less secure under the influence of climate change and ecological degradation (Fraser et al., 2005)(Moore, 2015). Urban Agriculture (UA) is an urban food production practice attaining more resilience in urban food systems by making cities less reliant on the import of food and the export of waste, more self-sufficient in food production, and by bringing a range of environmental and health benefits to the urban population (Bell & Cerulli, 2012). However, many structural barriers are still in place that make it difficult for the mainly small-scale community gardening initiatives to grow into a proper alternative food network. A lack of access to land, labor, water, seeds and technical support, or restrictive regulations and public health laws may act as barriers preventing the transformation of small-scale community gardening initiatives into a viable alternative urban food production system (Mourque, 2000)(Bell & Cerulli, 2012)(Roemers, 2014). In the Netherlands and Amsterdam in particular we can see that policy makers have started accommodating urban farmers by offering subsidies and giving the phenomenon more attention (Metaal et al., 2013)(Agenda Groen, 2015). Changing policy is central to reduce barriers that urban farmers run into because preconceptions of city planners and managers make it more difficult to institutionalize and expand farming in the city (Mourque, 2000, p. -

Clotel 184) with the Speed of a Bird, Having Passed the Avenue, She Began to Gain, and Presently She Was Upon the Long Bridge

European journal of American studies 15-2 | 2020 Summer 2020 Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/15701 DOI : 10.4000/ejas.15701 ISSN : 1991-9336 Éditeur European Association for American Studies Référence électronique European journal of American studies, 15-2 | 2020, « Summer 2020 » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 23 juin 2020, consulté le 08 juillet 2021. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/15701 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/ejas.15701 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 8 juillet 2021. European Journal of American studies 1 SOMMAIRE What on Earth! Slated Globes, School Geography and Imperial Pedagogy Mahshid Mayar Homecomings: Black Women’s Mobility in Early African American Fiction Anna Pochmara Hollywood’s Depiction of Italian American Servicemen During the Italian Campaign of World War II Matteo Pretelli “Being an Instance of the Norm”: Women, Surveillance and Guilt in Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road Vavotici Francesca Complicating American Manhood: Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time and the Feminist Utopia as a Site for Transforming Masculinities Michael Pitts Beyond Determinism: Geography of Jewishness in Nathan Englander’s “Sister Hills” and Michael Chabon’s The Yiddish Policemen’s Union Filip Boratyn Rummaging Through the Ashes: 9/11 American Poetry and the Transcultural Counterwitness Matthew Moran “Challenging Borders: Susanna Kaysen’s Girl, Interrupted as a Subversive Disability Memoir” Pascale Antolin Un/Seeing Campus Carry: Experiencing Gun Culture in Texas Benita Heiskanen -

Une Discographie De Robert Wyatt

Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Discographie au 1er mars 2021 ARCHIVE 1 Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Ce présent document PDF est une copie au 1er mars 2021 de la rubrique « Discographie » du site dédié à Robert Wyatt disco-robertwyatt.com. Il est mis à la libre disposition de tous ceux qui souhaitent conserver une trace de ce travail sur leur propre ordinateur. Ce fichier sera périodiquement mis à jour pour tenir compte des nouvelles entrées. La rubrique « Interviews et articles » fera également l’objet d’une prochaine archive au format PDF. _________________________________________________________________ La photo de couverture est d’Alessandro Achilli et l’illustration d’Alfreda Benge. HOME INDEX POCHETTES ABECEDAIRE Les années Before | Soft Machine | Matching Mole | Solo | With Friends | Samples | Compilations | V.A. | Bootlegs | Reprises | The Wilde Flowers - Impotence (69) [H. Hopper/R. Wyatt] - Robert Wyatt - drums and - Those Words They Say (66) voice [H. Hopper] - Memories (66) [H. Hopper] - Hugh Hopper - bass guitar - Don't Try To Change Me (65) - Pye Hastings - guitar [H. Hopper + G. Flight & R. Wyatt - Brian Hopper guitar, voice, (words - second and third verses)] alto saxophone - Parchman Farm (65) [B. White] - Richard Coughlan - drums - Almost Grown (65) [C. Berry] - Graham Flight - voice - She's Gone (65) [K. Ayers] - Richard Sinclair - guitar - Slow Walkin' Talk (65) [B. Hopper] - Kevin Ayers - voice - He's Bad For You (65) [R. Wyatt] > Zoom - Dave Lawrence - voice, guitar, - It's What I Feel (A Certain Kind) (65) bass guitar [H. Hopper] - Bob Gilleson - drums - Memories (Instrumental) (66) - Mike Ratledge - piano, organ, [H. Hopper] flute. - Never Leave Me (66) [H. -

Michail Kontopodis (Email: [email protected])

Fachbereich Erziehungswissenschaft und Psychologie Freie Universität Berlin F A B R I C A T I N G H U M A N D E V E L O P M E N T THE DYNAMICS OF ‘ORDERING’ AND ‘OTHERING’ IN AN EXPERIMENTAL SECONDARY SCHOOL (HAUPTSCHULE) Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt von Michail Kontopodis (Email: [email protected]) Fabricating Human Development Erstgutachter (First Supervisor): Prof. Dr. Martin Hildebrand-Nilshon, Arbeitsbereich Entwicklungs-psychologie, Fachbereich Erziehungswissenschaft und Psychologie, Freie Universität Berlin Zweitgutachter (Second Supervisor): Prof. Dr. Bernd Fichtner, Fachbereich 2: Erziehungswissenschaften, Universität Siegen Ort und Zeit der Disputation (Time and Place of Disputation): Berlin, 2. Juli 2007. 2 Contents Acknowledgements p. 4 Opening Intro Processing time: the dynamics of development as becoming p. 10 Map 1 Contexts and methodologies p. 38 1st Movement Map 2 Development as a technology of the self p. 57 Map 3 Communicating human development: the interactional organization of the self and of (non-) development p. 73 2nd Movement Map 4 Materializing time and institutionalizing human development p. 99 Map 5 Ordering and stabilizing human development p. 118 Map 6 Contrasting the School for Individual Learning-in-Practice with the Freedom Writers’ project p. 143 Finale Unlimiting human development p. 163 References p. 169 Appentix: Transcription and Coding of Oral Data p. 196 Disclaimer to Dissertation p. 198 To my parents Chrysoula & Jiannis, and to my brothers Manos & Dimitris And with respect and solidarity to Aanke, Barbara, Chriss, David, Florian, Nicola, Reinhard, Sélale, Wienfried and all the other teachers and students of the #School for Individual Learning-in-Practice# (name changed) Cover Picture: Composition of M.K.: a collage of two pictures drawn by students, a CV (see p. -

Master Streaming List 06112021

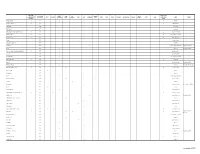

Heat Index Personal Star IMDb Rating Netflix Prime PBS Peacock/ IMDb 5=Intense/Dark Acorn Brit Box Hulu HBO Sundance Starz SHO ROKU Cinemax BBC America Disney+ EPIX USA Rating 1 to 5 Genre Notes (Out of 10) Streaming Video Passport NBC Freedive 1="Cozie" (best) Breaking Bad 5 9.5 ● 5 drama Game of Thrones 5 9.5 ● 5 action/thriller Chernobyl 9.4 ● docudrama The Wire 9.3 ● policing Sherlock (Benedict Cumberbatch) 3 9.2 ● ● 4 private detective The Sopranos 5 9.2 ● 5 heists/organized crme True Detective 5 9.0 ● 5 police detective Fargo 8.9 ● crime drama Only Fools & Horses 8.9 ● comedy Aranyelet 8.8 ● general mystery/crime English subtitles Dark 8.8 ● mystery English subtitles House of Cards (Netflix production) 4 8.8 ● political satire Narcos 8.8 ● organized crime Peaky Blinders 8.8 ● heists/organized crime The Sandbaggers 3 8.8 ● 4 espionage Umbre 8.8 ● organized crime English subtitles Better Call Saul 8.7 ● drama Breaking Bad prequel Brideshead Revisited 2 8.7 ● ● 5 period drama Danger UXB 8.7 ● drama Deadwood 8.7 ● drama Dexter 8.7 ● ● general mystery/crime Downton Abbey 1 8.7 ● ● period drama Fleabag 8.7 ● comedy Gomorrah 8.7 ● organized crime Italian with subtitles Rake 8.7 ● 2 legal Sacred Games 8.7 ● police detective Sherlock Holmes (Jeremy Brett) 2 8.7 ● 5 private detective The Bureau 8.7 ● police detective English subtitles The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel 8.7 ● drama The Shield 8.7 ● police detective The Thick of It 8.7 ● political drama Westworld 8.7 ● sci fi Poirot (David Suchet series) 1 8.6 ● ● 5 private detective Inspector Morse