Interculturalism, Intermediality and the Trope of Testimony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fra Statskonform Kirke Til Sosial Omformer?

TT-2015-2.book Page 164 Tuesday, May 19, 2015 3:10 PM Fra statskonform kirke til sosial omformer? Sju teser om Den norske kirkes rolle fra 1800-tallet til i dag HANS MORTEN HAUGEN F. 1971. Dr.jur og cand.polit. Professor, Institutt for diakoni og ledelse, Diakonhjemmet Høgskole. [email protected] Summary Sammendrag The Church of Norway has traditionally been a part of Den norske kirke har tradisjonelt vært en del av stats- the state of Norway. To what extent has this induced its makten i Norge. I hvilken grad har dette medført at de employees to be loyal to the state and the prevailing ansatte er lojale mot staten og den rådende samfunns- social order? Have leading church employees and orden? Har ledende kirkeansatte og ledere engasjert leaders engaged in or opposed social transformation seg i eller motarbeidet sosiale endringsbevegelser? movements? The article finds that the Church of Nor- Artikkelen peker på at Den norske kirke i mange way during many decisive phases has been in opposi- avgjørende faser de siste to hundre år har vært i oppo- tion to important social movements that have contrib- sisjon til viktige sosiale bevegelser som har bidratt til uted to the Norwegian welfare system and democracy. dagens norske velferdssystem og demokrati. Det er There are, however, countertrends to this overall pic- imidlertid flere unntak fra dette hovedbildet, og i dag ture, and currently the Church of Norway is highly crit- framstår Den norske kirke som svært kritisk til staten – ical of the state – for instance of its asylum policies. for eksempel i asylpolitikken. -

Die Verarbeitung Emotionaler Objekte Bei Borderline-Patientinnen: Eine Untersuchung Mit Ereigniskorrelierten Potentialen (EKP)

Klinik für Psychatrie und Psychotherapie III Universitätsklinikum Ulm Prof. Dr. Dr. Manfred Spitzer Ärztlicher Direktor Die Verarbeitung emotionaler Objekte bei Borderline-Patientinnen: Eine Untersuchung mit ereigniskorrelierten Potentialen (EKP) Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Medizin der Medizinischen Fakultät der Universität Ulm von Ute Neff Bad Saulgau 2018 Amtierender Dekan: Prof. Thomas Wirth 1. Berichterstatter: Prof. Carlos Schönfeld-Lecuona 2. Berichterstatter: Prof. Christiane Waller Tag der Promotion: 16. November 2018 Teile dieser Dissertation wurden bereits im folgenden Fachartikel veröffentlicht: Kiefer M, Neff U, Schmid MM, Spitzer M, Connemann BJ, Schönfeld-Lecuona C: Brain activity to transitional objects in patients with borderline personality disorder. Scientific Reports 7(1):13121 (2017) Inhaltsverzeichnis AbkürzungsverzeichnisVI 1 Einleitung1 1.1 Borderline-Persönlichkeitsstörung . .1 1.2 Bindungsverhalten . .7 1.2.1 Bindungstheorie . .7 1.2.2 Bindungsverhalten bei Borderline-Persönlichkeitsstörung . 10 1.3 Transitionale und emotionale Objekte . 12 1.3.1 Das transitionale Objekt . 12 1.3.2 Emotionale Objekte bei Erwachsenen . 13 1.3.3 Borderline-Patienten und emotionale Objekte . 14 1.4 Grundlagen der Elektroenzephalographie und ereigniskorrelierter Potentiale 15 1.5 EKP auf emotionale Objekte . 19 1.6 Ziel der Studie . 20 1.7 Hypothesen . 21 2 Material und Methoden 23 2.1 Stichprobenbeschreibung . 23 2.1.1 Probanden . 23 2.1.2 Ein- und Ausschlusskriterien . 24 2.1.3 Fragebögen zur Erfassung der Psychopathologie . 26 2.2 Stimuli . 30 2.3 Experiment zur Erkennung emotionaler Objekte . 31 2.4 Allgemeiner Ablauf der Studie . 34 2.5 EEG-Aufzeichnung und EKP-Analyse . 34 IV Inhaltsverzeichnis 2.6 Statistische Analyse . 36 3 Ergebnisse 40 3.1 Bewertung der Stofftiere . -

Extensions of Witness Fiction

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title "Alla människor har sin berättelse": Interculturalism, Intermediality and the Trope of Testimony in Novels by Ekman, Ørstavik and Petersen Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5xc593sq Author Martin, Suzanne Brook Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California “Alla människor har sin berättelse”: Interculturalism, Intermediality and the Trope of Testimony in Novels by Ekman, Ørstavik and Petersen By Suzanne Brook Martin A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Linda Rugg, Chair Professor John Lindow Professor Hertha D. Sweet Wong Professor Troy Storfjell Fall 2010 Abstract “Alla människor har sin berättelse”: Interculturalism, Intermediality and the Trope of Testimony in Novels by Ekman, Ørstavik and Petersen by Suzanne Brook Martin Doctor of Philosophy in Scandinavian University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Rugg, Chair This study focuses on Kerstin Ekman’s Vargskinnet trilogy (1999-2003), Hanne Ørstavik’s Presten (2004) and Martin Petersen’s Indtoget i Kautokeino (2004). The premise of this dissertation is that these novels provide a basis for investigating a subcategory of witness literature called witness fiction, which employs topoi of witness literature within a framework of explicitly fictional writing. Witness literature of all types relies on the experience of trauma by an individual or group. This project investigates the trauma of oppression of an indigenous group, the Sami, as represented in fiction by members of majority cultures that are implicated in that oppression. -

Depictions of Laestadianism 1850–1950

ROALD E. KRISTIANSEN Depictions of Laestadianism 1850–1950 DOI: https://doi.org/10.30664/ar.87789 Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) he issue to be discussed here is how soci- country. Until 1905, Norway was united ety’s views of the Laestadian revival has with Sweden, and so what happened in changed over the course of the revival T Sweden was also important for Norway. movement’s first 100 years. The article claims that society’s emerging view of the revival is This was even the case for a fairly long time characterized by two different positions. The first after 1905, especially with regard to a reli period is typical of the last part of the nineteenth gious movement that united people from century and is characterized by the fact that three Nordic countries (Sweden, Finland the evaluation of the revival took as its point of departure the instigator of the revival, Lars Levi and Norway). Laestadius (1800–61). The characteristic of Laes- The Laestadian revival originated in tadius himself would, it was thought, be char- northern Sweden during the late 1840s, acteristic of the movement he had instigated. and was led by the parish minister of Kare During this first period, the revival was sharply criticized. This negative attitude gradually suando, Lars Levi Læstadius (1800–61). changed from the turn of the century onwards. Within a few years, the revival spread The second period is characterized by greater to the neighbouring countries Finland openness towards understanding the revival on and Norway. In Norway, most parishes its own premises. -

L'histoire Du Livre Saami En Finlande

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 304 Sophie Alix Capdeville L’histoire du livre saami en Finlande Ses racines et son développement de 1820 à 1920 JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 304 Sophie Alix Capdeville L’histoire du livre saami en Finlande Ses racines et son développement de 1820 à 1920 Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistis-yhteiskuntatieteellinen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Agora-rakennuksen Lea Pulkkisen salissa helmikuun 17. päivänä 2017 kello 12. Thèse de doctorat présentée à la Faculté des Lettres et des Sciences sociales de l’université de Jyväskylä et soutenue publiquement dans la salle Lea Pulkkisen sali le 17 février 2017 à 12h UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2017 L’histoire du livre saami en Finlande Ses racines et son développement de 1820 à 1920 JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 304 Sophie Alix Capdeville L’histoire du livre saami en Finlande Ses racines et son développement de 1820 à 1920 UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2017 Editors Hannele Dufva Department of Language and Communication Studies, University of Jyväskylä Pekka Olsbo, Timo Hautala Open Science Centre, University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Music, Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Paula Kalaja, Department of Language and Communication Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Tarja Nikula, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Epp Lauk, Department of Languages and Communication Studies, University of Jyväskylä Cover pictures: Itkonen, Lauri 1906. Raammat Historja Hakkarainen, Aukusti 1906. Kievrra ja Kievrab Andelin, Anders 1860. -

HOT MESS 2Nd Draft.Fdr

HOT MESS by Jenni Ross Based on the novel, "THE HEARTBREAKERS" By Pamela Wells Second Draft 12/16/09 Goldsmith-Thomas Productions 239 Central Park West, Suite 6A New York, NY 10024 (212) 243-4147 OVER BLACK WE HEAR THE INTRO TO “LITTLE GREEN BAG” BY THE GEORGE BAKER SELECTION (ICONIC INTRODUCTION TO RESERVOIR DOGS). COLD OPEN: EXT. ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PLAYGROUND - DAY/FLASHBACK Four, eleven year old girls, strut confidently across the playground wearing sunglasses, a’la Reservoir Dogs. Other kids move out of their way. BEGIN TITLE SEQUENCE OVER MONTAGE: The four girls come to the aid of another kid being bullied by an older boy on the playground; they TP someone’s house by the light of the moon, laughing uncontrollably; they throw their hands high in the air on a roller coaster, screaming; they start a food fight in the cafeteria and are hauled into detention; the girls play kickball and kick ass. Kelly tags a boy with the ball as she slides onto the base. ALEXIA (V.O.) Welcome to my halcyon days. A simpler time when math homework didn’t require a calculator and your underwear still covered your ass. They raise their hands in class, unashamed that they know the answer. ALEXIA (V.O.) (CONT’D) Back then my friends and I were on top of the pre-pubescent world. We were happy to be ourselves and no amount of Britney Spears videos or American Apparel ads could convince us otherwise. The girls walk by a large print ad for Guess Jeans - Raven zips back into the shot and defaces the model by “crossing her eyes” with a Sharpie. -

Møteinnkalling

Møteinnkalling Utvalg: Kvænangen Oppvekst- og omsorgsutvalget Møtested: 1. etg., Kommunehuset Dato: 10.12.2009 Tidspunkt: 09:00 Eventuelt forfall må meldes snarest på tlf. 77778800. Vararepresentanter møter etter nærmere beskjed. Burfjord 02.12.09 Liv Reidun Olsen leder Saksliste Utv.saksnr Sakstittel U.Off Arkivsaksnr PS 2009/61 Samisk skolehistorie - søknad om støtte 2009/10013 PS 2009/62 Kvænangen kommunes kulturpris for 2009 2009/8297 PS 2009/63 Godkjenning av Burfjord barnehage 2009/9550 PS 2009/64 Framtidig investering i skole/barnehage 2009/9991 PS 2009/65 Budsjett barnehage/skole 2009/9995 PS 2009/66 Referatsaker RS 2009/34 Søknad om prosjektstøtte. 2009/1993 RS 2009/35 Søknad om skolefri 2009/688 Kvænangen kommune Arkivsaknr: 2009/10013 -2 Arkiv: 223 Saksbehandler: Rita Boberg Pedersen Dato: 27.11.2009 Saksfremlegg Utvalgssak Utvalgsnavn Møtedato 2009/61 Kvænangen Oppvekst- og omsorgsutvalget 10.12.2009 Samisk skolehistorie - søknad om støtte Vedlegg 1 Søknad 2 Prosjektbeskrivelse 3 Redaktørgruppa 4 Budsjett Rådmannens innstilling Søknaden avslås. Saksopplysninger Det er igangsatt et verk på fem bøker á ca. 460 sider som blir presentert både på samisk og norsk. Forlaget som blir brukt er ”Davvi Girji”. Bind 1 ble utgitt i 2005, - hvor Paula Simonsen fra Kvænangen har en artikkel – ”Oppvokst på ei løgn”, bind 2 i 2007 og bind 3 i juni 2009. Innholdslista til bind 4 er vedtatt, og en del av artiklene er behandlet og godkjent eller sendt i retur for forbedring. Til bind 5 er store deler av stoffet samlet inn, men det gjenstår en del artikler og mye bearbeiding. Redaksjonskomiteen og forlaget regner med å kunne klare å utgi bind 4 og 5 henholdsvis sommeren 2010 og 2011. -

How Urban Farming Initiatives Are Changing the Policy Regime in Amsterdam

Ticket to paradise or how I learned to stop worrying and love the transition: How urban farming initiatives are changing the policy regime in Amsterdam Research design Name: John-Luca de Vries Studentnumber: 10762779 Datum: July 6th, 2018 Word count: 15821 Supervisors: John Grin & Anna Aalten Introduction The stability of urban food systems depends on a properly functioning global market, open trade routes, affordable energy and stable weather conditions, factors which will likely become less secure under the influence of climate change and ecological degradation (Fraser et al., 2005)(Moore, 2015). Urban Agriculture (UA) is an urban food production practice attaining more resilience in urban food systems by making cities less reliant on the import of food and the export of waste, more self-sufficient in food production, and by bringing a range of environmental and health benefits to the urban population (Bell & Cerulli, 2012). However, many structural barriers are still in place that make it difficult for the mainly small-scale community gardening initiatives to grow into a proper alternative food network. A lack of access to land, labor, water, seeds and technical support, or restrictive regulations and public health laws may act as barriers preventing the transformation of small-scale community gardening initiatives into a viable alternative urban food production system (Mourque, 2000)(Bell & Cerulli, 2012)(Roemers, 2014). In the Netherlands and Amsterdam in particular we can see that policy makers have started accommodating urban farmers by offering subsidies and giving the phenomenon more attention (Metaal et al., 2013)(Agenda Groen, 2015). Changing policy is central to reduce barriers that urban farmers run into because preconceptions of city planners and managers make it more difficult to institutionalize and expand farming in the city (Mourque, 2000, p. -

Clotel 184) with the Speed of a Bird, Having Passed the Avenue, She Began to Gain, and Presently She Was Upon the Long Bridge

European journal of American studies 15-2 | 2020 Summer 2020 Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/15701 DOI : 10.4000/ejas.15701 ISSN : 1991-9336 Éditeur European Association for American Studies Référence électronique European journal of American studies, 15-2 | 2020, « Summer 2020 » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 23 juin 2020, consulté le 08 juillet 2021. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/15701 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/ejas.15701 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 8 juillet 2021. European Journal of American studies 1 SOMMAIRE What on Earth! Slated Globes, School Geography and Imperial Pedagogy Mahshid Mayar Homecomings: Black Women’s Mobility in Early African American Fiction Anna Pochmara Hollywood’s Depiction of Italian American Servicemen During the Italian Campaign of World War II Matteo Pretelli “Being an Instance of the Norm”: Women, Surveillance and Guilt in Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road Vavotici Francesca Complicating American Manhood: Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time and the Feminist Utopia as a Site for Transforming Masculinities Michael Pitts Beyond Determinism: Geography of Jewishness in Nathan Englander’s “Sister Hills” and Michael Chabon’s The Yiddish Policemen’s Union Filip Boratyn Rummaging Through the Ashes: 9/11 American Poetry and the Transcultural Counterwitness Matthew Moran “Challenging Borders: Susanna Kaysen’s Girl, Interrupted as a Subversive Disability Memoir” Pascale Antolin Un/Seeing Campus Carry: Experiencing Gun Culture in Texas Benita Heiskanen -

Folk I Nord Møtte Prester Fra Sør Kirke- Og Skolehistorie, Minoritets- Og

KÅRE SVEBAK Folk i Nord møtte prester fra sør Kirke- og skolehistorie, minoritets- og språkpolitikk En kildesamling: 65 LIVHISTORIER c. 1850-1970 KSv side 2 INNHOLDSREGISTER: FORORD ......................................................................................................................................... 10 FORKORTELSER .............................................................................................................................. 11 SKOLELOVER OG INSTRUKSER........................................................................................................ 12 RAMMEPLAN FOR DÅPSOPPLÆRING I DEN NORSKE KIRKE ........................................................... 16 INNLEDNING .................................................................................................................................. 17 1. BERGE, OLE OLSEN: ................................................................................... 26 KVÆFJORD, BUKSNES, STRINDA ....................................................................................................... 26 BUKSNES 1878-88 .......................................................................................................................... 26 2. ARCTANDER, OVE GULDBERG: ................................................................... 30 RISØR, BUKSNES, SORTLAND, SOGNDAL, SIGDAL, MANDAL .................................................................. 30 RISØR 1879-81 .............................................................................................................................. -

Michail Kontopodis (Email: [email protected])

Fachbereich Erziehungswissenschaft und Psychologie Freie Universität Berlin F A B R I C A T I N G H U M A N D E V E L O P M E N T THE DYNAMICS OF ‘ORDERING’ AND ‘OTHERING’ IN AN EXPERIMENTAL SECONDARY SCHOOL (HAUPTSCHULE) Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt von Michail Kontopodis (Email: [email protected]) Fabricating Human Development Erstgutachter (First Supervisor): Prof. Dr. Martin Hildebrand-Nilshon, Arbeitsbereich Entwicklungs-psychologie, Fachbereich Erziehungswissenschaft und Psychologie, Freie Universität Berlin Zweitgutachter (Second Supervisor): Prof. Dr. Bernd Fichtner, Fachbereich 2: Erziehungswissenschaften, Universität Siegen Ort und Zeit der Disputation (Time and Place of Disputation): Berlin, 2. Juli 2007. 2 Contents Acknowledgements p. 4 Opening Intro Processing time: the dynamics of development as becoming p. 10 Map 1 Contexts and methodologies p. 38 1st Movement Map 2 Development as a technology of the self p. 57 Map 3 Communicating human development: the interactional organization of the self and of (non-) development p. 73 2nd Movement Map 4 Materializing time and institutionalizing human development p. 99 Map 5 Ordering and stabilizing human development p. 118 Map 6 Contrasting the School for Individual Learning-in-Practice with the Freedom Writers’ project p. 143 Finale Unlimiting human development p. 163 References p. 169 Appentix: Transcription and Coding of Oral Data p. 196 Disclaimer to Dissertation p. 198 To my parents Chrysoula & Jiannis, and to my brothers Manos & Dimitris And with respect and solidarity to Aanke, Barbara, Chriss, David, Florian, Nicola, Reinhard, Sélale, Wienfried and all the other teachers and students of the #School for Individual Learning-in-Practice# (name changed) Cover Picture: Composition of M.K.: a collage of two pictures drawn by students, a CV (see p. -

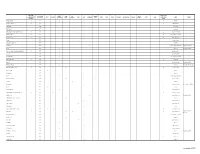

Master Streaming List 06112021

Heat Index Personal Star IMDb Rating Netflix Prime PBS Peacock/ IMDb 5=Intense/Dark Acorn Brit Box Hulu HBO Sundance Starz SHO ROKU Cinemax BBC America Disney+ EPIX USA Rating 1 to 5 Genre Notes (Out of 10) Streaming Video Passport NBC Freedive 1="Cozie" (best) Breaking Bad 5 9.5 ● 5 drama Game of Thrones 5 9.5 ● 5 action/thriller Chernobyl 9.4 ● docudrama The Wire 9.3 ● policing Sherlock (Benedict Cumberbatch) 3 9.2 ● ● 4 private detective The Sopranos 5 9.2 ● 5 heists/organized crme True Detective 5 9.0 ● 5 police detective Fargo 8.9 ● crime drama Only Fools & Horses 8.9 ● comedy Aranyelet 8.8 ● general mystery/crime English subtitles Dark 8.8 ● mystery English subtitles House of Cards (Netflix production) 4 8.8 ● political satire Narcos 8.8 ● organized crime Peaky Blinders 8.8 ● heists/organized crime The Sandbaggers 3 8.8 ● 4 espionage Umbre 8.8 ● organized crime English subtitles Better Call Saul 8.7 ● drama Breaking Bad prequel Brideshead Revisited 2 8.7 ● ● 5 period drama Danger UXB 8.7 ● drama Deadwood 8.7 ● drama Dexter 8.7 ● ● general mystery/crime Downton Abbey 1 8.7 ● ● period drama Fleabag 8.7 ● comedy Gomorrah 8.7 ● organized crime Italian with subtitles Rake 8.7 ● 2 legal Sacred Games 8.7 ● police detective Sherlock Holmes (Jeremy Brett) 2 8.7 ● 5 private detective The Bureau 8.7 ● police detective English subtitles The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel 8.7 ● drama The Shield 8.7 ● police detective The Thick of It 8.7 ● political drama Westworld 8.7 ● sci fi Poirot (David Suchet series) 1 8.6 ● ● 5 private detective Inspector Morse