“Supporting Rural Community Adaptation to Climate Change in Mountainous Regions of Djibouti”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The making of hazard: a social-environmental explanation of vulnerability to drought in Djibouti Daher Aden, Ayanleh Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 The making of a hazard: a social-environmental explanation of vulnerability to drought in Djibouti Thesis submitted to King’s College London For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ayanleh Daher Aden Department of Geography Faculty of Social Science and Public Policy December 2014 “The key to riding the wave of chaos is not to resist it, but to allow yourself to know you are a part of the energy of chaos, allowing a new form of organization in it, rather than imposing your old system organization upon it. -

Project Proposal to the Adaptation Fund

PROJECT PROPOSAL TO THE ADAPTATION FUND Project/Programme Category: Regular Country/ies: Djibouti Title of Project/Programme: Integrated Water and Soil Resources Management Project (Projet de gestion intégrée des ressources en eau et des sols PROGIRES) Type of Implementing Entity: Multilateral Implementing Entity Implementing Entity: International Fund for Agricultural Development Executing Entity/ies: Ministry of Agriculture, Water, Fisheries and Livestock Amount of Financing Requested: 5,339,285 (in U.S Dollars Equivalent) i Table of Contents PART I: PROJECT/PROGRAMME INFORMATION ......................................................................... 1 A. Project Background and Context ............................................................................. 1 Geography ............................................................................................... 1 Climate .................................................................................................... 2 Socio-Economic Context ............................................................................ 3 Agriculture ............................................................................................... 5 Gender .................................................................................................... 7 Climate trends and impacts ........................................................................ 9 Project Upscaling and Lessons Learned ...................................................... 19 Relationship with IFAD PGIRE Project ....................................................... -

Planning and Implementing Ecosystem Based Adaptation (Eba) in Djibouti’S Dikhil and Tadjourah Regions

5/6/2020 WbgGefportal Project Identification Form (PIF) entry – Full Sized Project – GEF - 7 Planning and implementing Ecosystem based Adaptation (EbA) in Djibouti’s Dikhil and Tadjourah regions Part I: Project Information GEF ID 10180 Project Type FSP Type of Trust Fund LDCF CBIT/NGI CBIT NGI Project Title Planning and implementing Ecosystem based Adaptation (EbA) in Djibouti’s Dikhil and Tadjourah regions Countries Djibouti Agency(ies) UNEP Other Executing Partner(s) Executing Partner Type Ministry of Habitat, Urbanism, and Environment Government GEF Focal Area Climate Change Taxonomy Biodiversity, Biomes, Climate Change, Climate Change Adaptation, Focal Areas, Sustainable Land Management, Land Degradation, Land Degradation Neutrality, Private Sector, Type of Engagement, Civil Society, Stakeholders, Communications, Gender Mainstreaming, Gender Equality, Gender results areas, Food Security in Sub-Sahara Africa, Integrated Programs, Sustainable Cities, Capacity, Knowledge and Research, Knowledge Generation, Food Security, Land Productivity, Income Generating Activities, Community-Based Natural Resource Management, Sustainable Livelihoods, Sustainable Agriculture, Improved Soil and Water Management Techniques, Ecosystem Approach, Drought Mitigation, Wetlands, Least Developed Countries, Livelihoods, Mainstreaming adaptation, Climate resilience, Community-based adaptation, Ecosystem-based Adaptation, Beneficiaries, Participation, Information Dissemination, Consultation, Behavior change, Awareness Raising, Public Campaigns, SMEs, Community Based -

Download the Project Brief

Consulting services to support IGAD with the implementation of the Regional Migration Fund Supporting migrants, refugees, and host communities in the Horn of Africa and Nile Valley region NIRAS supports the Regional Migration Fund with its aim to create economic opportunities, improve living conditions, and promote social cohesion among the high number of displaced people in the region, as well as locals affected by their arrival. The two towns of the same name - Moyale in Kenya and Moyale in Ethiopia - are located on the main transport route from Addis Ababa to Nairobi, and make up a vibrant transport, trade, and services hub. The Horn of Africa and Nile Valley region comprises FMU, which is responsible for the setup, operation, the countries of Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, So- and management of the RMF, the preparation and malia, Sudan, South Sudan, and Uganda and has a selection of specific interventions, and support to in- population of more than 250 million people. To- dividual measures at project level. gether, these eight countries have established the Tor Jorgensen trade bloc the Intergovernmental Authority on De- RMF projects take place within two investment Project Manager velopment (IGAD). Its aim is to assist and comple- windows. Investment Window 1 (IW1) aims to promo- T: +255 7456 63377 [email protected] ment Member States’ national efforts through in- te local economic development and employment creased cooperation, enhanced food security an growth, improve migrant and host community liveli- environmental protection, improved peace and hoods and strengthen social cohesion, e.g. though security and humanitarian affairs; and promotion of dialogue forums, conflict resolution mechanisms, economic cooperation and integration. -

Horn of Africa Crisis Situation Report No

Horn of Africa Crisis Situation Report No. 28 23 December 2011 This report is produced by OCHA Eastern Africa in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It is issued by OCHA in New York. It covers the period from 16 to 23 December. The next report will be issued on 30 December. I. HIGHLIGHTS/KEY PRIORITIES • Tensions remain high in North Eastern Province of Kenya following a series of explosive attacks targeting military and police convoys in the area. • Aid workers have further reduced operations in the Dadaab refugee camps following heightened insecurity. • WHO has called on health partners to intensify cholera preventative activities in Mogadishu following an increase in cases. II. Situation Overview While drought conditions have eased in many locations due to the recent rains, drought conditions are expected to worsen in parts of the Horn of Africa in the coming months as the dry season sets in. A new food security analysis of the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) system in Djibouti has indicated that the food security situation in Obock Region has deteriorated from ‘Stressed’ (IPC Phase 2) to ‘Crisis’ (IPC Phase 3).Deterioration in food security conditions is now likely in coastal and southeast areas as well. In Ethiopia, even as the seasonal deyr (October-December) rains continue in most lowland areas of southern and south-eastern Ethiopia, drought conditions are expected to worsen in the northernmost parts of the Afar Region and parts of northern Somali Region in the coming month. On the other hand, drought conditions in the northern, north-eastern and southern parts of Kenya have significantly eased following good rainfall received in the October-December short rains season.In Somalia, while the deyr rains have subsided in many parts of Lower and Middle Juba regions, flooding continues to affect many settlements in Middle Juba. -

Climate Change Adaptation in the Arab States Best Practices and Lessons Learned

Climate Change Adaptation in the Arab States Best practices and lessons learned United Nations Development Programme 2018 | 1 UNDP partners with people at all levels of society to help build nations that can withstand crisis, and drive and sustain the kind of growth that improves the quality of life for everyone. On the ground in nearly 170 countries and territories, we offer global perspective and local insight to help empower lives and build resilient nations. www.undp.org The Global Environment Facility (GEF) was established on the eve of the 1992 Rio Earth Summit to help tackle our planet’s most pressing environmental problems. Since then, the GEF has provided over $17 billion in grants and mobilized an additional $88 billion in financing for more than 4000 projects in 170 countries. Today, the GEF is an international partnership of 183 countries, international institutions, civil society organizations and the private sector that addresses global environmental issues. www.thegef.org United Nations Development Programme July 2018 Copyright © UNDP 2018 Manufactured in Bangkok Bangkok Regional Hub (BRH) United Nations Development Programme 3rd Floor United Nations Service Building Rajdamnern Nok Avenue, Bangkok, 10200, Thailand www.adaptation-undp.org Authors: The report preparation was led by Tom Twining-Ward in close collaboration with Kishan Khoday, with Cara Tobin as lead author and Fadhel Baccar, Janine Twyman Mills, Walid Ali and Zubair Murshed as contributing authors. The publication was professionally reviewed by fellow UNDP colleagues, Amal Aldababseh, Greg Benchwick, Hanan Mutwaki, Mohamed Bayoumi, and Walid Ali. Valuable external expert review, comments, and suggestions were provided by Hussein El-Atfy (Arab Water Council), Ibrahim Abdel Gelil (Arabian Gulf University), and William Dougherty (Climate Change Research Group). -

MVT DE BASE.Pdf

TT r:-I REPUBLISUE DE DJIBOUTI Unité' Égalité - Paix Ministère de l'Éducatlon Nationale ;d;;Ë Èoimauon Professionnelle oireEîGnffite ff* t ÛP De I'Administration - ûL, 1'J-, -il,l.-" 8 2102 o t2ssl 35-20-52 o 35-08-50 DJTBOUTI ,Jfl l,-rJl i,11, i ,, TélécoPie : (253) 35-68-19 ulJi r,lill NOTE DE SERVIVE N%aÉIDGA Du 12Auo2021 de OBJET : Mouvement des enseignants indiqué ci-dessous p9" les noms suivent sont mutés commÇ ' Les enseignants dont défrnis par la conlmlsslon ra uur"^L, .ri èr., crairement rannée scolaire ziii-tzozzsur væux des enseignants ' chargée du mouvement et les Il s'agit de : DISCIPLI NOUVELLE ANCIENNE ÀFFECTATION AFFECTATTox- NES _- l\I(rlID^ NOM/PII,L1\U1VI RANDA FR A.BAKAI(I A-rrrvr'orv I" "'"" BALBALA9 I " SAGALLOU FR ewelo voHeveo BAL 3 2. E,r-eztp ALI OUNF. FR BB6 J. .q,eot AHNaep ooueLrH LrôI I FR ô'-r rr^r roeDhr ^ ALI SABIEH 2 4. ^T]ËN DORALEH FR § M(Jnl\lvlEL/ rùrvr^rL . ROURE ABI)[ NAT,AY AF FR - 6. aeoru.AHl-q4glB§uEpl NIKI{II,3 AE '7. FR HODAN NUKU HASSAN I§IUIilTL PLAINE 8. ABDILLAHI INTT-iI FR 4HIvlEll b!!4! BIS 9. ABDIRAHMAN r FI{ FR Q5 2 10. aBDIRAHMAN E!,MLAL! T FR ALI SABIEH rrTr'IJ P,ÔI IR AI-EH ll TJ ÀVARI,FH ÀffittraoHAMED 't'^ FR I ÀIJ 12. ^nn^T FR PK12 TNTTATT l3 ABDOULMIZ OSMAN EWI AI FR BOULAUS t4; Eôou--luertuneHpRvoHeveo ceÀN FR ALAILI D@ 15. lo.rnrn r{aDF.R ALI ISMAEL ANNEXE 3 BIS ESOOUI.TADERHASSAN BB7 FR rr^r!^ÀI^rIn - ECOLE D! arlru4 16. -

Djibouti, 2007

DJIBOUTI 7 – 12 december 2007 At the end of 2007, we were a group of Swedes visiting Ethiopia and Djibouti. It was a private trip led by Eric Renman, a very keen mammal watcher, and because the main focus of this trip was mammals, and Eric knew that I am a mammal freak, I was offered to join. Because there is no report from this trip online and Djibouti is quite unknown as a mammal destination, I decided to make a short report on the Djibouti part of the trip. As I write this 2020 (during corona restrictions) I can’t remember everything and my camera equipment wasn’t very good either. Probably the situation in the country has changed a lot too. So not very up-to-date! It didn’t start very well. When it was my turn to check in for the flight to Djibouti in Addis Abeba, they just told me the plane was full. Most of the group, except for two more of us, went through. It was incredible hot and stressful and we start to plan to take a taxi to the border but suddenly we were allowed to board. After a late arrival we took a taxi to the pre-booked hotel in Djibouti Ville, just to find it was full . When our tour leader solved this problem the rest of us waited outside, and was offered by a man to buy lighters that could emit light with either Saddam Hussein or Usama Bin Laden as the motive. December 8 We got our two Land Rover Defenders in the morning, without contracts or payments, and started bird watching around the city. -

Overview of Non-Contributory Social Protection Programmes in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region Through a Child and Equity Lens

UNICEF/Romenzi Overview of Non-contributory Social Protection Programmes in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region Through a Child and Equity Lens Anna Carolina Machado, Charlotte Bilo, Fábio Veras Soares and Rafael Guerreiro Osorio International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (IPC-IG) Empowered lives. Resilient nations. Copyright© 2018 International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth United Nations Development Programme and the United Nations Children’s Fund This publication is one of the outputs of the UN to UN agreement between the International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (IPC-IG) – and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Middle East and North Africa Regional Office (MENARO). The International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (IPC-IG) is a partnership between the United Nations and the Government of Brazil to promote South–South learning on social policies. The IPC-IG is linked to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Brazil, the Ministry of Planning, Development, Budget and Management of Brazil (MP) and the Institute for Applied Economic Research (Ipea) of the Government of Brazil. Research Coordinators Research Assistants Anna Carolina Machado (IPC-IG) Anna Davidsen, Anne Esser, Charlotte Bilo (IPC-IG) Barbara Branco, Caroline Scott, Fábio Veras Soares (IPC-IG) Elena Kühne, Fernando Damazio, Rafael Guerreiro Osorio (Ipea and IPC-IG) Lara Aquino and Yasmin Scheufler Researchers United Nations Online Volunteers Eunice Godevi (IPC-IG, DAAD fellow) Dorsaf James, Mohamed Ayman, Imane Helmy (IPC-IG, independent consultant) Sarah Abo Alasrar and Susan Jatkar Joana Mostafa (Ipea) Pedro Arruda (IPC-IG) Designed by the IPC-IG Raquel Tebaldi (IPC-IG) Publications team: Sergei Soares (Ipea and IPC-IG) Roberto Astorino, Flávia Amaral, Wesley Silva (IPC-IG) Rosa Maria Banuth and Manoel Salles Rights and permissions – all rights reserved. -

As of 17 April 2020, the Ministry of Health Has Confirmed 732 Cases Of

IOM Djibouti is continuing to provide assistance for stranded migrants inside and gloves) at checkpoints, border COVID-19 prevention and response the country due to border closures in crossings and medical centres. support in the form of donations, Ethiopia and Yemen. The Mission is also in discussion with the capacity building to medical staff and The Organization is working closely with Ministry of Women and Family to government officials, and awareness the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry provide COVID-19 protection services raising on proper hygiene practices for of Health and distributing hygiene and to street children in Djibouti city. migrants and host communities. protection non-food items (soap, IOM is also providing multi-sectoral disinfectant, handwashing stations, masks As of 17 April 2020, the Ministry of Health has confirmed 732 COVID-19 on the economy, on 14 April, the Ports and Free cases of COVID-19 in Djibouti and two deaths. In the Balbala Zones Authority decided to grant a 82.5% reduction in port suburb in Djibouti, Al Rahma hospital has become a new tariffs for 60 days to all Ethiopian exports. This gesture in critical epicentre of epidemic. The establishment has been put in time was welcomed by the Ethiopian Prime Minister. The quarantine since by the Ministry of Health. The Government of Government confirmed that the road corridor to Ethiopia will Djibouti has reported testing 7,486 individuals and continues to remain open. All terminal handling charges will be free for strategically target people who have potentially come into Ethiopian exporters for 60 days, as a COVID-19 solidarity contact with those who tested positive for COVID-19. -

Environmental Management of Assal-Fiale Geothermal Project in Djibouti: a Comparison with Geothermal Fields in Iceland

Orkustofnun, Grensasvegur 9, Reports 2015 IS-108 Reykjavik, Iceland Number 7 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT OF ASSAL-FIALE GEOTHERMAL PROJECT IN DJIBOUTI: A COMPARISON WITH GEOTHERMAL FIELDS IN ICELAND Ali Barreh Adaweh Ministry of Energy in charge of Natural Resources Cite Ministerielle, Djibouti REPUBLIC OF DJIBOUTI [email protected] ABSTRACT The geological characteristics of the Assal rift are favourable for the development of geothermal energy in Djibouti. The Government plans to exploit the geothermal resources in the Assal region to enable public access to a reliable, renewable and affordable source of energy. The Assal-Fiale geothermal project is located on a site that has scientific, ecological and tourist importance. Using the geothermal resource is believed to be a positive way to generate electricity in the area but improper management of the resource can cause possible negative impacts on the environment. Environmental impacts assessment will help to understand and minimize negative impacts of the project and with good management can support the environmental, economic and social goals of sustainability. This report presents the possible environmental impacts of the project and their management which aims to minimize them in accordance with national and international regulations and the geothermal utilization experience gained in Iceland. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Purpose of this study The geothermal potential in Djibouti is estimated around 1000 MWe, distributed among thirteen sites and mainly located in the Lake Assal region. The government’s plans, with its first geothermal project, are to exploit the geothermal resources in the Lake Assal region to enable public access to a reliable, renewable and affordable source of energy. -

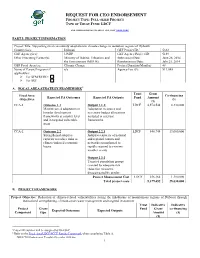

Request for Ceo Endorsement Project Type: Full-Sized Project Type of Trust Fund: Ldcf

REQUEST FOR CEO ENDORSEMENT PROJECT TYPE: FULL-SIZED PROJECT TYPE OF TRUST FUND: LDCF FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT GEF, VISIT THEGEF.ORG PART I: PROJECT INFORMATION Project Title: Supporting rural community adaptation to climate change in mountain regions of Djibouti Country(ies): Djibouti GEF Project ID:1 5332 GEF Agency(ies): UNDP GEF Agency Project ID: 5189 Other Executing Partner(s): Ministry of Habitat, Urbanism and Submission Date: June 26, 2014 the Environment (MHUE) Resubmission Date: July 25, 2014 GEF Focal Area (s): Climate Change Project Duration(Months) 48 Name of Parent Program (if n/a Agency Fee ($): 511,048 applicable): For SFM/REDD+ For SGP A. FOCAL AREA STRATEGY FRAMEWORK2 Trust Grant Focal Area Co-financing Expected FA Outcomes Expected FA Outputs Fund Amount Objectives ($) ($) CCA-1 Outcome 1.1 Output 1.1.1: LDCF 4,574,544 8,330,000 Mainstreamed adaptation in Adaptation measures and broader development necessary budget allocations frameworks at country level included in relevant and in targeted vulnerable frameworks areas CCA-2 Outcome 2.2 Output 2.2.1 LDCF 548,744 19,000,000 Strengthened adaptive Adaptive capacity of national capacity to reduce risks to and regional centers and climate-induced economic networks strengthened to losses rapidly respond to extreme weather events Output 2.2.2 Targeted population groups covered by adequate risk reduction measures, disaggregated by gender. Project Management Cost LDCF 256,164 1,300,000 Total project costs 5,379,452 28,630,000 B. PROJECT FRAMEWORK Project Objective: Reduction of climate-related vulnerabilities facing the inhabitants of mountainous regions of Djibouti through institutional strengthening, climate-smart water management and targeted investment Trust Indicative Indicative Project Grant Fund Grant co-financing Expected Outcomes Expected Outputs Component type Amount ($) ($) 1Project ID number will be assigned by GEFSEC.