Class 9: the Puccini Persuasion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1718Studyguidetosca.Pdf

TOSCA An opera in three acts by Giocomo Puccini Text by Giacosa and Illica after the play by Sardou Premiere on January 14, 1900, at the Teatro Constanzi, Rome OCTOBER 5 & 7, 2O17 Andrew Jackson Hall, TPAC The Patricia and Rodes Hart Production Directed by John Hoomes Conducted by Dean Williamson Featuring the Nashville Opera Orchestra CAST & CHARACTERS Floria Tosca, a celebrated singer Jennifer Rowley* Mario Cavaradossi, a painter John Pickle* Baron Scarpia, chief of police Weston Hurt* Cesare Angelotti, a political prisoner Jeffrey Williams† Sacristan/Jailer Rafael Porto* Sciarrone, a gendarme Mark Whatley† Spoletta, a police agent Thomas Leighton* * Nashville Opera debut † Former Mary Ragland Young Artist TICKETS & INFORMATION Contact Nashville Opera at 615.832.5242 or visit nashvilleopera.org. Study Guide Contributors Anna Young, Education Director Cara Schneider, Creative Director THE STORY SETTING: Rome, 1800 ACT I - The church of Sant’Andrea della Valle quickly helps to conceal Angelotti once more. Tosca is immediately suspicious and accuses Cavaradossi of A political prisoner, Cesare Angelotti, has just escaped and being unfaithful, having heard a conversation cease as she seeks refuge in the church, Sant’Andrea della Valle. His sis - entered. After seeing the portrait, she notices the similari - ter, the Marchesa Attavanti, has often prayed for his release ties between the depiction of Mary Magdalene and the in the very same chapel. During these visits, she has been blonde hair and blue eyes of the Marchesa Attavanti. Tosca, observed by Mario Cavaradossi, the painter. Cavaradossi who is often unreasonably jealous, feels her fears are con - has been working on a portrait of Mary Magdalene and the firmed at the sight of the painting. -

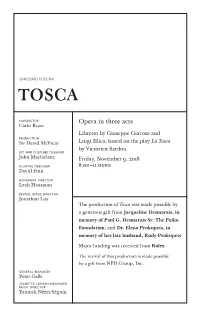

11-09-2018 Tosca Eve.Indd

GIACOMO PUCCINI tosca conductor Opera in three acts Carlo Rizzi Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and production Sir David McVicar Luigi Illica, based on the play La Tosca by Victorien Sardou set and costume designer John Macfarlane Friday, November 9, 2018 lighting designer 8:00–11:00 PM David Finn movement director Leah Hausman revival stage director Jonathon Loy The production of Tosca was made possible by a generous gift from Jacqueline Desmarais, in memory of Paul G. Desmarais Sr; The Paiko Foundation; and Dr. Elena Prokupets, in memory of her late husband, Rudy Prokupets Major funding was received from Rolex The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from NPD Group, Inc. general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 970th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIACOMO PUCCINI’S tosca conductor Carlo Rizzi in order of vocal appearance cesare angelot ti a shepherd boy Oren Gradus Davida Dayle a sacristan a jailer Patrick Carfizzi Paul Corona mario cavaradossi Joseph Calleja floria tosca Sondra Radvanovsky* baron scarpia Claudio Sgura spolet ta Brenton Ryan sciarrone Christopher Job Friday, November 9, 2018, 8:00–11:00PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA Sondra Radvanovsky Chorus Master Donald Palumbo in the title role and Fight Director Thomas Schall Joseph Calleja as Musical Preparation John Keenan, Howard Watkins*, Cavaradossi in Puccini’s Tosca Carol Isaac, and Jonathan C. Kelly Assistant Stage Directors Sarah Ina Meyers and Mirabelle Ordinaire Met Titles Sonya Friedman Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Carol Isaac Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes constructed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This production uses gunshot effects. -

Kansas State University Orchestra Programs 1990—2018 Updated January 13, 2018 David Littrell, Conductor

Kansas State University Orchestra Programs 1990—2018 updated January 13, 2018 David Littrell, conductor 1990-1991 October 16, 1990 Tragic Overture, Op. 81 Brahms Oboe Concerto R. Strauss Dr. Sara Funkhouser, oboe Symphony No. 4 in C Minor (“Tragic”) Schubert December 11, 1990 Orchestral Suite No. 1 in C Major, BWV 1066 JS Bach “Vedrai, carino” from Don Giovanni Mozart Dayna Snook, mezzo-soprano Scaramouche Suite, 2nd & 3rd mvts. Milhaud Christopher Goins, alto saxophone “Son vergin vezzosa” from I Puritani Bellini Ai-ze Wang, soprano Symphony No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 10 Shostakovich April 4-5-6, 1991 The Magic Flute (Opera) Mozart April 23, 1991 Overture to Ruy Blas Mendelssohn Symphony No. 101 in D Major (“Clock”) Haydn Symphony No. 5 in Eb Major, Op. 82 Sibelius 1991-1992 October 1, 1991 Overture to Il Signor Bruschino Rossini Concerto Grosso for Four String Orchestras Vaughan Williams assisting musicians: Manhattan public school string students Symphony No. 2 in B Minor Borodin repeat performance October 2, 1991 at Concordia KS October 24-25-26, 1991 West Side Story Bernstein December 9, 1991 In Memoriam, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Sinfonia concertante in Eb Major, K. 364 Mozart Cora Cooper, violin Melinda Scherer Bootz, viola Requiem, K. 626 Mozart John Alldis, guest conductor soloists: Lori Zoll, Juli Borst, Rob Fann, Andy Stuckey KSU Concert Choir March 3, 1992 Overture to Der Freischütz von Weber “Faites-lui mes aveux” from Faust Gounod Juli Borst, mezzo-soprano “Ah, per sempre” from I Puritani Bellini Andy Stuckey, baritone Concerto in D Haydn Lisa Leuthold, horn Symphony No. -

LANGUAGE ARTS: What's That Word Again?

LANGUAGE ARTS: What’s that word again? Students will Read “The Characters” and the Tosca Synopsis Read the Tosca Synopsis from the Metropolitan Opera Complete and discuss the Activity Worksheets Copies for Each Student: Tosca Synopsis, “The Characters”, Tosca Synopsis from the Metropolitan Opera, Activity Worksheets Copies for the Teacher: Language Arts lesson plan, Tosca Synopsis, “The Characters”, Tosca Synopsis from the Metropolitan Opera, Activity Worksheets Getting Ready Decide which section(s) of the worksheet you wish your group to complete. Prepare internet access for the Tosca online listening selections. Gather pens, pencils, dictionaries, thesauruses and additional writing paper as needed for your group. Introduction Read the Tosca Synopsis and “The Characters” to your students. Have your students read the Tosca Synopsis from the Metropolitan Opera specific to their grade level, and complete the accompanying activity worksheets. Guided/Independent Practice Depending on your grade level, the ability of your students, and time constraints, you may choose to have students work as a whole class, in small groups, with a partner, or individually. Read the directions on the Activity Worksheet. Provide instructions and model the activity as needed. Have students complete the portion(s) of the Activity Worksheet you have chosen with opportunity for questions. Evaluation Have students share their answers individually or by groups and explain why they gave their answers. The teacher may want to guide the discussion with the sample answers provided. 2015-2016 Educational Programs page 1 of 8 TEKS English Language Arts and Reading 6th Grade 110.18.B.2 Reading/Vocabulary Development Students understand new vocabulary and use it when reading and writing. -

C4acfallprogram.Pdf

PROGRAM Welcome Chris Grapentine, Concert4aCause Co-Founder Bells Reverie Sandra Eithun Pavane Maurice Ravel, arr. Sharon E. Rogers Esther Metz Yost Handbell Choir, Director Sheree Clark Esther Yost, Chris & Carolyn Grapentine, Mary Ellen Hagel; Paul & Al Clark; Anne & Phil Daws-Lazar Trout Quintet in A major, D. 667, opus 14 Franz Schubert Allegro vivace Die Forelle Theme & Variations: Andantino-Allegretto Finale: Allegro giusto A2SO Strings & Piano Ensemble: Dan Stachyra, violin; Janine Bradbury, viola; Sarah Cleveland, cello, Gregg Powell, bass; Kathryn Goodson, piano; Glenn Perry, tenor Arias Giacomo Puccini Recondita Armonia – Tosca Nessun Dorma – Turandot Ch'ella mi Creda – La Fanciulla del West Russell Kerns, saxophone; Joshua Marzan, piano *** Intermission *** Comment Student Advocacy Center Peri Stone-Palmquist, Executive Director Branden Magee, Student British Isles Lizbie Brown Gerald Finzi Quintet no. 1 in C minor Ralph Vaughan Williams Allegro con fuoco Andante Fantasia quasi variazioni A2SO Strings & Piano; Glenn Perry Closing Paul Duke, Co-Pastor, FBC & Terry McGinn, Pastor, NCC *** Reception *** PERFORMERS Sheree Clark, Bell Choir Director Sheree Clark, a native of Northville, MI, spent several childhood years between Michigan and Arkansas and has resided in Ann Arbor for the last thirty years. Ms. Clark received her Bachelor of Science in Nursing from Eastern Michigan University in 1979. Since then she continues to be active in a variety of nursing roles doing Patient Advocacy in Adult and Pediatric settings. Ms. Clark has taken courses at the Ecumenical Theological Seminary in Detroit where she is pursuing a Masters of Divinity for ordination in the American Baptist Churches. Ms. Clark is a licensed minister and is on staff at Northside Community Church of Ann Arbor as Ministry Associate for Congregational Care, Parish Nurse, and Bell Choir Director. -

Adam Diegel Tenor

Adam Diegel Tenor Adam Diegel regularly earns international acclaim for his impassioned dramatic sensibilities, powerful voice, and for his classic leading man looks. From a performance as Cavaradossi in Tosca at Glimmerglass Opera, Opera News raved: “The opera became a showdown between Adam Diegel’s impulsive, shaggily handsome Cavaradossi and Lester Lynch’s fearsome, animalistic Scarpia… (Diegel’s) spacious, Italianate tenor…delivered a stirring ‘Recondita armonia’ and built ‘E lucevan le stelle’ masterfully from hushed intimacy to an unfettered cri de coeur.” This season, Diegel’s engagement include appearances in two of his signature roles: as Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly at Opera Hong Kong and Palm Beach Opera; and Don José in Carmen at San Francisco Opera, PORTopera, and Opera San Antonio. Additionally, Diegel will sing the title role in Verdi’s Don Carlo with Lithuanian National Opera, Ruggerio in La rondine with Opera Santa Barbara, and return to The Metropolitan Opera to sing Ismaele in Nabucco. Mr. Diegel made his Metropolitan Opera début as Froh in Robert Lepage’s landmark production of Das Rheingold conducted by Maestro James Levine, and later reprised the performance under Fabio Luisi. Further appearances at The Met include Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly under Plácido Domingo and Ismaele in Nabucco under Paolo Carignani. Other notable recent U.S. engagements include: Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly at Atlanta Opera, Fort Worth Opera, Arizona Opera, Opera San Antonio, and Kentucky Opera; Ismaele in Nabucco at Opera Philadelphia; Cavaradossi in Tosca at Vancouver Opera, Glimmerglass Opera, Seattle Opera, and Arizona Opera; Don José in Carmen at Glimmerglass Opera, Opera Theatre of St. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 109, 1989-1990

A GALA OPERATIC EVENING MlRELLA FRENI, soprano and Peter Dvorsky, tenor Members of the J3 Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by John Fiore Presented by the BOSTON OPERA ASSOCIATION Sunday, February 11, 1990, at 8 p.m. Symphony Hall, Boston m ® The Boston Opera Association Mrs. Russell J. Rowell, President Vice-Presidents V.J Hon. Charles Francis Mahoney Anthony D. Ostrom James D. St. Clair David C. Crockett Hon. Lawrence T. Perera Chairman, Board of Overseers Chairman, Board of Directors Robert L. Culver Robert L. Klivans Treasurer Secretary Bruce R. Bengston Michael J. Puzo Assistant Treasurer Assistant Secretary Board of Directors Mrs. Frank G. Allen Dr. Melvin D. Field Dr. Daniel H. Perlman Mr. John T. Bennett, Jr. Mr. Eugene M. Freedman Mr. William S. Reardon Mrs. John M. Bleakie Mr. Martin Gantshar Mr. John Ryan Mrs. Mary Louise Cabot Mr. Gerard A. Glass Mrs. George Lee Sargent Mr. Robert Cahners Mr. Milton L. Glass Mrs. Jacquelyn Scheinbart Mr. William I. Cowin Miss Sally Hurlbut Mr. Robert H. Scott Dean Phyllis Curtin Mrs. Myra Kraft Dr. Lawrence T. Shields Miss Catharine-Mary Donovan Mrs. J. Peter Lyons Mr. Johannes Spanjaard Mr. George Ellison Mr. Donald M. Manzelli Mr. Charles A. Steward Mrs. Harris Fahnestock Mrs. Nancy Rice Morss Mrs. Lucius Thayer Board of Overseers Mr. Frank G. Allen, Jr. Mrs. Henry S. Hall, Jr. Mrs. Barbara C. Riley Mr. Robert B.M. Barton Mrs. Henry M. Halvorson Miss Ann Sargent Mrs. Ralph Bradley Mr. Robert Hilliard Mrs. Frederic W. Schwartz Mr. Max Canter Mrs. Robert Douglas Hunter Mrs. Theodore C. Sturtevant Mr. -

The Bohemians

(THE BOHEMIANS) BY CIM I 12615 Act I. Rudolph's Song "Your Tiny Hand Is Frozen" (Che gelida manina), Db English and Italian $ .50* n2 Act I. Rudolph's Song "Your Tiny Hand Is Frozen" (Che gelida manina), C English and Italian .50* b& Act I. Rudolph's Song "Your Tiny Hand Is Frozen" (Che gelida manina), Bb English and Italian .50* 114078 Act I. Mimi's Song "They Call Me Mimi" (Si mi chiamano Mimi), D English and Italian .50* 114079 Act I. Mimi's Song "They Call Me Mimi" (Si mi chiamano Mimi), C English and Italian .50* 114080 Act I. Mimi's Song "They Call Me Mimi" (Si mi chiamano Mimi), Bb English and Italian .50* 114081 Act I. Duet, Mimi and Rudolph, "Lovely Maid in the Moonlight" (O soave fanciulla), English and Italian .65* 114082 Act II. Musetta's Valse Song "As Thro' the Street" (Quando me'n vo soletta), E English and Italian .50* 114083 Act II. Musetta's Valse Song 'As Thro' the Street" (Quando me'n vo soletta), Efc English and Italian .50* 114084 .50* 114085 Act II. Musetta's Valse Song 'As Thro' the Street" (Quando me'n vo soletta), D English and Italian Act II. Musetta's Valse Song "As Thro the Street" (Quando me'n vo soletta), Three-part Female Chorus .15 114001 .50* 114087 Act III. Mimi's Farewell "To the Home That She Left" (Donde lieta), English and Italian Act IV. Colline's Song "A Last Good-bye" (Vecchia zimarra, senti), English and Italian .65* 114088 .65* 114089 Act IV. -

Tosca Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) Libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa Act I: the Church of Sant’Andrea Della Valle

feb. 21, 23, 26 classical series SEGERSTROM CENTER FOR THE ARTS renée and henry segerstrom concert hall concerts begin at 8 p.m. preview talk with alan chapman begins at 7 p.m. presents 2012-2013 HAL & JEANETTE SEGERSTROM FAMILY FOUNDATION CLASSICAL SERIES Carl St.Clair, conductor | Eric Einhorn, director Pacific Chorale — John Alexander, artistic director Robert M. Istad, assistant conductor and chorusmaster Southern California Children’s Chorus — Lori Loftus, director Tosca giacomo puccini (1858-1924) libretto by luigi illica and giuseppe giacosa act i: the church of sant’andrea della valle INTERMISSION act ii: palazzo farnese act iii: the platform of the castel sant’angelo CAST tosca Claire rutter, soprano cavaradossi Brian Jagde, tenor scarpia George gagnidze, baritone angelotti Ryan kuster, bass-baritone spoletta Dennis petersen, tenor sacristan Michael gallup, bass sciarrone Ralph cato, baritone Jailer Emmanuel miranda, baritone Kathy Pryzgoda, lighting designer Julia Noulin-Merat, scenic designer Paul DiPierro, digital media designer PACIFIC SYMPHONY PROUDLY RECOGNIZES ITS OFFICIAL PARTNERS official airline official hotel official television station pacific symphony broadcasts are made possible by a generous grant from the saturday, feb. 23, performance is broadcast live on kusc, the official classical radio station of pacific symphony. the simultaneous streaming of this broadcast over the internet at kusc.org is made possible by the generosity of the musicians of pacific symphony. pacific symphony gratefully acknowledges the support of its 12,500 subscribing patrons. thank you! Pacific Symphony • 5 notes by michael clive the title role over 3,000 times. closer to our own day, the 20th- century diva maria callas was equally legendary as floria tosca, and scarpia’s epithet for tosca — la divina — became the affectionate italian nickname for callas. -

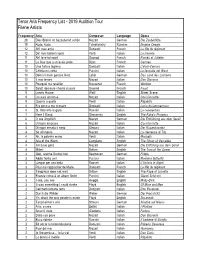

WTO 2019 Audition Tour Aria Frequency Data

Tenor Aria Frequency List - 2019 Audition Tour Filene Artists Frequency Aria Composer Language Opera 28 Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön Mozart German Die Zauberflöte 19 Kuda, kuda Tchaikovsky Russian Engene Onegin 12 Ah! mes amis Donizetti French La fille du régiment 12 De' miei bollenti spiriti Verdi Italian La traviata 11 Ah! leve-toi soleil Gounod French Roméo et Juliette 11 La fleur que tu m'avais jetée Bizet French Carmen 10 Una furtiva lagrima Donizetti Italian L'elisir d'amore 10 Ch'ella mi creda Puccini Italian La fanciulla del West 10 Dein ist mein ganzes Herz Lehár German Das Land des Lächelns 10 Il mio tesoro Mozart Italian Don Giovanni 10 Pourquoi me reveiller Massenet French Werther 10 Salut! demeure chaste et pure Gounod French Faust 9 Lonely House Weill English Street Scene 9 Un aura amorosa Mozart Italian Cosi fan tutte 9 Questa o quella Verdi Italian Rigoletto 8 Fra poco a me ricovero Donizetti Italian Lucia di Lammermoor 8 Si, ritrovarla io giuro Rossini Italian La cenerentola 7 Here I Stand Stravinsky English The Rake's Progress 6 O wie ängstlich Mozart German Die Entführung aus dem Serail 6 Un'aura amorosa Mozart Italian Cosi fan tutte 5 Di rigori armato il seno Strauss Italian Der Rosenkavalier 4 Se all’impero Mozart Italian La clemenza di Tito 4 Ah, la paterna mano Verdi Italian Macbeth 4 Aria of the Worm Corigliano English The Ghost of Versailles 4 Ich baue ganz Mozart German Die Entfürung aus dem Serail 4 Miles! Britten English The Turn of the Screw 3 Gott, welche Dunkel hier Beethoven German Fidelio 3 Addio fiorito -

Music by Giacomo Puccini Libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa Based on La Tosca by Victorien Sardou

TOSCA Music by Giacomo Puccini Libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa Based on La Tosca by Victorien Sardou TABLE OF CONTENTS ADDITIONAL RESOURCES FOR TEACHERS Thank you to our generous sponsors..2 Preface & Objectives…………………….... 18 Cast of characters…………………... 3 What is Opera Anyway?..................... 19 Brief Overview…………………….. 3 Opera in Not Alone……………………….. 19 Detailed synopsis with musical ex…. 4 Opera Terms………………………………. 20 About the composer………………… 12 Where Did Opera Come From?.................... 21 Historical context………………….. 14 Why Do Opera Singers Sound Like That?.... 22 The creation of the opera………….. 15 How Can I Become an Opera Singer?........... 22 Opera Singer Must-Haves…………………. 23 How to Make an Opera……………………. 24 Jobs in Opera………………………………. 25 Opera Etiquette…………………………….. 26 Discussion Questions………………………. 27 Educational Activities Sponsors…………….. 28 1 PLEASE JOIN US IN THANKING OUR GENEROUS SEASON SPONSORS ! 2 TOSCA First performance on January 14, 1900 at the Teatro Costanzi in Rome, Italy Cast of characters Floria Tosca , a celebrated singer Soprano Mario Cavaradossi, an artist; Tosca’s lover Tenor Baron Scarpia , Chief of Roman police Baritone Cesare Angelotti , former Consul to the Roman Republic Bass A Sacristan Bass Spoletta, a police agent Tenor Sciarrone , a gendarme Bass A Jailer Bass A Shepherd boy Treble Soldiers, police agents, altar boys, noblemen and women, townsfolk, artisans Brief Overview In 1800, the city of Rome was a virtual police state. The ruling Bourbon monarchy was threatened by agitators advocating political and social reform. These included the Republicans, inspired to freedom and democracy by the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, and Napoleon. These forces opposed the Royalists who advocated the continuation of the existing monarchy in league with the Roman Catholic Church. -

Andrea Bocelli Three Centuries of Love

02-10-2019 Bocelli new.qxp_GP 1/31/19 3:11 PM Page 1 02-10-2019 Bocelli new.qxp_GP 1/31/19 3:11 PM Page 2 Sunday, February 10, 2019, at 5:00PM Andrea Bocelli, Three Centuries of Love Sunday, February 17, 2019, at 5:00PM Part Two DELIBES Les Filles de Cadix Boléro ANDREA BOCELLI AIDA GARIFULLINA GOUNOD Roméo et Juliette “L’amour … Ah, lêve-toi soleil” THREE CENTURIES OF LOVE ANDREA BOCELLI featuring GOUNOD Roméo et Juliette “Va, je t’ai pardonné … Nuit d’hyménée” AIDA GARIFULLINA, soprano AIDA GARIFULLINA, ANDREA BOCELLI ISABEL LEONARD, mezzo-soprano NADINE SIERRA, soprano GOUNOD Faust ‘Kermesse’ Waltzes special guest MASSENET Werther “Il faut nous séparer” LUCA PISARONI, bass-baritone ISABEL LEONARD, ANDREA BOCELLI with PUCCINI Manon Lescaut Orchestral Paraphrase MEMBERS OF THE METROPOLITAN OPERA ORCHESTRA EUGENE KOHN, guest conductor PUCCINI Tosca “Recondita armonia” ANDREA BOCELLI Part One PUCCINI La Bohème “O soave fanciulla” ISABEL LEONARD, ANDREA BOCELLI MASSENET Le cid Ballet “Navarraise” MASSENET Le cid “Ah, tout est bien finí … Ô, souverain” ANDREA BOCELLI VERDI I Lombardi “La mia letizia infondere” ANDREA BOCELLI VERDI Un Giorno di Regno Overture VERDI Rigoletto “È il sol dell’anima … Addio, addio” AIDA GARIFULLINA, ANDREA BOCELLI ROSSINI La Cenerentola “Naqui all’affanno” ISABEL LEONARD DONIZETTI La Fille du Régiment “Pour mon âme” ANDREA BOCELLI DONIZETTI Lucia di Lammermoor “M’odi … Sulla tomba che rinserra” NADINE SIERRA, ANDREA BOCELLI (Continued) The Metropolitan Opera House Please make certain your cellular phone, The Metropolitan Opera House Please make certain your cellular phone, pager, or watch alarm is switched off.