A Rba S Icula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Prov. Tutte

SEZ SEZ SEZ SEZ SEZ NOMINATIVO DEL LEGALE DATA DECRETO O O O COMUNE CAP DENOMINAZIONE DELL'ORGANIZZAZIONE INDIRIZZO DELL'ORGANIZZAZIONE RECAPITI O O RAPPRESENTANTE NUMER NUMER PROV. A B C D E DECRET REGISTR TEL. 0922/442115 FAX 0922/26906 - 660556 CELL 3663319273 E- AG AGRIGENTO 92100 ASS.NE AVULSS DI AGRIGENTO ONLUS VIA EMPEDOCLE N. 145 FERA GUELI GIOVANNA A B C 340 07/03/1996 68 MAIL [email protected] AG AGRIGENTO 92100 ASSOCIAZIONE DONATORI AUTONOMA SANGUE A.D.A.S. VIA PLATONE N. 5/E TEL. 092/2586588 E-MAIL [email protected] DI FRANCESCO FILIPPO B 1547 09/10/1996 125 AG AGRIGENTO 92100 ASS.NE A.V.I.S. SEZIONE COMUNALE PIAZZA PRIMAVERA N. 15 CELL. 3208638897 CUMBO GASPARE B 1094 27/06/2000 432 AG AGRIGENTO 92100 VOLONTARIATO ITALIANO MISSIONARIO AMORE E CARITA' VIA MONCADA N. 02 tel. 092/613089 cell. 3382612199 E-MAIL [email protected] MAGRO GIUSEPPE A B 2162 18/12/2000 457 TEL. FAX 0922/607239 CELL 3666178934 E-MAIL AG AGRIGENTO 92010 ASS.NE MADRE TERESA DI CALCUTTA ONLUS VIA CAVALERI MAGAZZENI N. 111 NOBILE ANTONIO A 67 09/03/2001 512 [email protected] AG AGRIGENTO 92100 GRUPPO FRATRES FRANCESCO SAMMARTINO VIA BELVEDERE, 91 (fraz. Giardina-Gallotti) CELL. 327 9544584 FARRUGGIA CALOGERO B 3653 28/10/2002 597 AG AGRIGENTO 92100 ASS.NE FOCUS GROUP ONLUS SALITA FRANCESCO SALA N. 15 TEL.0922 22922 fax 0922 25457 GALLO CARRABBA ANTONINA A C 355 23/02/2004 705 AG AGRIGENTO 92100 ASS.NE ARMONIA SOCIALE ONLUS SALITA FRANCESCO SALA N. -

ATO Idrico Di Ragusa Tabella 3.16 Reti Fognarie Proposta Di

ATO Idrico di Ragusa Proposta di aggiornamento del Piano d'Ambito di Ragusa Tabella 3.16 Reti fognarie Stato di Stato di Stato di Tipo di conservazione Lunghezza Comune servito Denominazione rete Età conservazione conservazione Funzionalità fognatura opere [km] complessiva opere civili elettromecc. Settore civile ACATE RETE FOGNARIA NERA DI ACATE separata 1950-70 sufficiente sufficiente sufficiente sufficiente 20,4 RETE FOGNARIA ZONA non ACATE separata 2008 2 ARTIGIANA+COMMERCIANTI funzionante CHIARAMONTE GULFI RETE FOGNARIA NERA nera 1950-70 sufficiente sufficiente sufficiente sufficiente 6,4 CHIARAMONTE GULFI RETE FOGNARIA NERA nera > 1990 buono sufficiente sufficiente sufficiente 1,6 CHIARAMONTE GULFI RETE FOGNARIA NERA nera 1970-80 buono sufficiente sufficiente sufficiente 3,2 CHIARAMONTE GULFI RETE FOGNARIA NERA nera <1950 scarso sufficiente sufficiente sufficiente 3,2 CHIARAMONTE GULFI RETE FOGNARIA NERA nera 1980-90 buono sufficiente sufficiente sufficiente 1,6 RETE FOGNARIA NERA PIANO CHIARAMONTE GULFI nera > 1990 buono buono buono buona 2,5 DELL'ACQUA CHIARAMONTE GULFI RETE FOGNARIA NERA ROCCAZZO nera 1980-90 buono buono buono buona 8 COMISO RETE FOGNARIA NERA separata > 1990 buono buono buono insufficiente 6 COMISO RETE FOGNARIA NERA separata 1970-80 sufficiente sufficiente sufficiente sufficiente 24 COMISO RETE FOGNARIA NERA separata 1950-70 sufficiente buono buono insufficiente 4 COMISO RETE FOGNARIA NERA separata > 1990 buono sufficiente sufficiente sufficiente 32 COMISO RETE FOGNARIA NERA separata 1980-90 sufficiente sufficiente -

Buccini the Merchants of Genoa and the Diffusion of Southern Italian Pasta Culture in Europe

Anthony Buccini The Merchants of Genoa and the Diffusion of Southern Italian Pasta Culture in Europe Pe-i boccoin boin se fan e questioin. Genoese proverb 1 Introduction In the past several decades it has become received opinion among food scholars that the Arabs played the central rôle in the diffusion of pasta as a common food in Europe and that this development forms part of their putative broad influence on culinary culture in the West during the Middle Ages. This Arab theory of the origins of pasta comes in two versions: the basic version asserts that, while fresh pasta was known in Italy independently of any Arab influence, the development of dried pasta made from durum wheat was a specifically Arab invention and that the main point of its diffusion was Muslim Sicily during the period of the island’s Arabo-Berber occupation which began in the 9th century and ended by stages with the Norman conquest and ‘Latinization’ of the island in the eleventh/twelfth century. The strong version of this theory, increasingly popular these days, goes further and, though conceding possible native European traditions, posits Arabic origins not only for dried pasta but also for the names and origins of virtually all forms of pasta attested in the Middle Ages, albeit without ever providing credible historical and linguistic evidence; Clifford Wright (1999: 618ff.) is the best known proponent of this approach. In AUTHOR 2013 I demonstrated that the commonly held belief that lasagne were an Arab contribution to Italy’s culinary arsenal is untenable and in particular that the Arabic etymology of the word itself, proposed by Rodinson and Vollenweider, is without merit: both word and item are clearly of Italian origin. -

PROTOCOLLO D'intesa Per Istituire L'area Di Crisi Industriale Complessa

PROTOCOLLO D’INTESA per istituire l’area di crisi industriale complessa del Polo industriale di Siracusa tra Regione Siciliana Comune di Augusta Comune di Avola Comune di Canicattini Bagni Comune di Cassaro Comune di Ferla Comune di Floridia Comune di Melilli Comune di Priolo Gargallo Comune di Siracusa Comune di Solarino Comune di Sortino Isab srl – Gruppo LUKOIL Sonatrach Raffineria ltaliana srl Sasol ltaly spa Versalis spa ERG Power srl AIR Liquide Italia spa Confindustria Sicilia CGIL Sicilia CISL Sicilia UIL Sicilia UGL Sicilia Autorità di Sistema Portuale del Mare Sicilia orientale Camera di Commercio del Sud Est Sicilia Premesso che - le industrie petrolchimiche e chimiche rappresentano settori strategici per la crescita e per lo sviluppo industriale del Sistema paese, costituendo il punto di partenza per moltissimi comparti industriali, rifornendoli di prodotti essenziali per la loro attività e per i loro manufatti; - per la natura di industria globalizzata, risente più di altri dei cambiamenti e delle incertezze legati alle diverse politiche economiche e di decarbonizzazione dei principali Paesi produttori; - il settore deve essere orientato e supportato per garantire i necessari livelli di innovazione, puntando a prodotti che assicurino una maggiore sostenibilità ambientale, in linea con quanto previsto dalla nuova politica energetica prevista dal Piano Energia e Clima 2030 (PNIEC 2030) e dagli obiettivi di neutralità carbonica al 2050 espressi dall’Unione Europea con il Green Deal; - il Polo industriale di Siracusa (di seguito -

Pieghevole Alcantara 4 Ante 2

“A good wine is poetry and it is an art to produce it”: it is around this insight that the winery Dalla felice intuizione che un buon vino è “poesia” e per farlo ci vuole “arte”, nasce Al-Cantàra Al-Cantàra was created. Albeit young, the winery is establishing a reputation for itself Percorso per le Cantine . Negli ultimi anni, l’azienda si è affermata a livello nazionale ed internazionale nationally and internationally thanks to the high quality of its wines, which have been awarded site in Randazzo c/da Feudo S. Anastasia grazie all’altissima qualità dei suoi vini, riconosciuta da diversi importanti premi e, da ultimo, important prizes including the recent astounding results achieved at Vinitaly with seven wines dallo strepitoso risultato conseguito al Vinitaly: con sette vini segnalati nel 5 StarWines - selected for the 5 StarWines - The Book. There, Al-Cantàra was the second most awarded The Book, Al-Cantàra è stata la seconda azienda più premiata in Sicilia e la sesta in Italia! Il winery in Sicily and the sixth in Italy! The sophisticated and modern packaging is another packaging sofisticato e moderno è un altro tratto distintivo dei prodottiAl-Cantàra , le cui distinctive feature of the Al-Cantàra products, whose unmistakable labels are painted by inconfondibili etichette sono impreziosite dalle suggestive rappresentazioni di giovani young Sicilian artists and seek to evoke theterroir , the traditions and the culture of Sicily . artisti siciliani ed esaltano letradizioni , la cultura ed il territorio etneo . The winery takes its name from the river which flows, from the slopes of MountEtna , below L’azienda prende il nome dal fiume che, sulle pendici dell’Etna , lambisce la contrada Feudo S. -

This Regulation Shall Be Binding in Its Entirety and Directly Applicable in All Member States

12. 8 . 91 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 223/ 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION (EEC) No 2396/91 of 29 July 1991 fixing for the 1990/91 marketing year the yields of olives and olive oil THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Whereas the measures provided for in this Regulation are in accordance with the opinion of the Management Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Committee for Oils and Fats, Economic Community, Having regard to Council Regulation No 136/66/EEC of 22 September 1966 on the establishment of a common HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION : organization of the market in oils and fats ('), as last amended by Regulation (EEC) No 1720/91 (2) ; Article 1 Having regard to Council Regulation (EEC) No 2261 /84 of 17 July 1984 laying down general rules on the granting 1 . For the 1990/91 marketing year, yields of olives and of aid for the production of olive oil and of aid to olive oil olive oil and the relevant production zones shall be as producer organizations (3), as last amended by Regulation specified in Annex I hereto . (EEC) No 3500/90 (4), and in particular Article 19 thereof, 2. The production zones are defined in Annex II . Whereas Article 18 of Regulation (EEC) No 2261 /84 provides that yields of olives and olive oil should be fixed for each homogeneous production zone on the basis of Article 2 information supplied by the producer Member States ; This Regulation shall enter into force on the third day Whereas, in view of the information received, it is appro following its publication in the Official Journal of the priate to fix these yields as specified in Annex I hereto ; European Communities. -

MICROZONAZIONE SISMICA Relazione Illustrativa MS Livello 1 Regione Sicilia Comune Di Giarratana

Regione Siciliana - Presidenza Dipartimento della Protezione Civile Attuazione dell'Articolo 11 della Legge 24 giugno 2009, n.77 MICROZONAZIONE SISMICA Relazione Illustrativa MS Livello 1 Regione Sicilia Comune di Giarratana Convenzione in data 20/12/2011 tra il Dipartimento Regionale della Protezione Civile e l’Università degli Studi di Palermo: Indagini di Microzonazione sismica di Livello I in diversi Comuni della Regione Sicilia ai sensi dell’OPCM 3907/2010 Contraente: Soggetto realizzatore: Data: Regione Siciliana - Presidenza Università degli Studi di Palermo Novembre 2012 Dipartimento della Protezione Civile 2 INDICE Premessa Pag. 4 1. Introduzione 5 1.1 Finalità degli studi 5 1.2 Descrizione generale dell’area 6 1.3 Definizione della cartografia di base 7 1.4 Elenco archivi consultati 8 1.5 Definizione dell’area da sottoporre a microzonazione 8 2. Definizione della pericolosità di base e degli eventi di riferimento 10 2.1 Sismicità storica della Sicilia sud – orientale 10 2.2 Sismicità storica e pericolosità sismica nel comune di Giarratana 14 2.3 Faglie attive 20 2.4 Pericolosità geo-idrologica 21 3. Assetto geologico e geomorfologico 21 3.1 Inquadramento geologico 21 3.2 Assetto Tettonico 23 3.3 Caratteri morfologici, stratigrafici e tettonici del territorio di Giarratana 23 3.3.1 Caratteri morfologici 23 3.3.2 Litostratigrafia 28 3.3.2.1 Formazione Ragusa 29 3.3.2.2 Formazione Tellaro 29 3.3.2.3 Coperture 29 3.3.3 Lineamenti tettonici di Giarratana 31 4. Dati geotecnici e geofisici 31 4.1 Il database 31 4.2 Unità geologico – litotecniche 33 4.3 Indagini geofisiche precedenti 34 4.4 Il metodo HVSR 34 4.5 Indagini HVSR 37 5. -

1 Il Paesaggio Culturale Della Contea Di Modica

Il paesaggio culturale della Contea di Modica Elena DI BLASI Dipartimento di Economia e Territorio, Facoltà di Economia, Università degli Studi di Catania, c.so Italia, 55 –95129- Catania, tel.095/375344 int.336, fax 095/377174, e-mail: [email protected] Riassunto. La ricerca vuole offrire spunti di riflessione su un’ area della Sicilia dalla storia antica: la Contea di Modica. Una storia, quella della Contea, che affonda le proprie radici indietro nel tempo, scandita da diverse dominazioni che hanno lasciato i “segni” impressi sul territorio, interessato da nefasti eventi naturali che hanno determinato via via l’assetto urbanistico, politico, economico e sociale. Per meglio comprendere le caratteristiche dei centri, che un tempo fecero parte della gloriosa Contea, si è cercato di cogliere gli aspetti percettivi anche attraverso la cartografia storica, che contribuisce a dare il “senso dei luoghi” e la loro “immagine”. Obiettivo del lavoro è quello di evidenziare le forti potenzialità turistiche di questo territorio, non soltanto per la presenza di un patrimonio artistico di valore inestimabile, eredità delle variegate ed alterne vicende umane espresse nelle diverse forme di cultura materiale ed immateriale, ma anche per i grandi giacimenti naturali. Sono stati, inoltre, indagati i punti di forza di Ragusa, Modica e Scicli, città che appartennero all’antica Contea. Questi tre centri fanno parte con Caltagirone, Catania, Militello in Val di Catania e Noto di un ampio progetto denominato il “Piano di Gestione del Val di Noto” che ha come obiettivo l’analisi di tutte le risorse comprese in questa vasta area avente come unico comune denominatore il Barocco, già riconosciuto dall’Unesco patrimonio dell’umanità, e coglierne nel contempo le differenze. -

Necropoli Paleocristiane E Chiese Rupestri Dell'altopiano Acrense. La

Santino Alessandro Cugno Necropoli paleocristiane e chiese rupestri dell’altopiano acrense. La «Canicattini Cristiana» di Salvatore Carpinteri Il territorio del moderno centro abitato di Canicattini Bagni, situato a circa 20 Km ad ovest di Siracusa nel margine orientale dell’altopiano acrense, pur estrema- mente significativo per la ricchezza delle sue testimonianze archeologiche, solo in rare occasioni è stato sottoposto ad indagini scientifiche sistematiche e approfondite. Nella letteratura archeologica specialistica, infatti, il nome di Canicattini è legato quasi esclusivamente a rinvenimenti casuali di manufatti dalla varia tipologia e cro- nologia (l’industria litica del Paleolitico Superiore, i crateri a figure rosse di contrada Bagni, le argenterie paleocristiane di Piano Milo, gli anelli bizantini della serie co- siddetta “angeliana”) oppure a sommarie segnalazioni di villaggi e sepolcri rurali ri- salenti alla Tarda Antichità e all’Alto Medioevo. 1 In qualità di titolare della cattedra di Archeologia Cristiana presso l’Università di Catania dall’a.a. 1948-49 all’a.a. 1962-63, l’illustre archeologo Giuseppe Agnello era solito affidare ai propri studenti tesi di laurea sulle necropoli paleocristiane e le epigrafi dei centri da cui essi provenivano; 2 i dati raccolti nel corso di queste ricer- 1 M. FRASCA , s.v. Canicattini Bagni , in G. NENCI -G. VALLET (a cura di), Bibliografia topogra- fica della colonizzazione greca in Italia e nelle isole tirreniche , vol. IV, Roma 1985, pp. 350-354 con bibliografia precedente; S. A. CUGNO , Osservazioni sul tesoro di Canicattini Bagni e su alcuni gioielli bizantini dell’altopiano acrense (Siracusa) , in «Bizantinistica» 12 (2010), pp. 79-92. La prima men- zione di un “casale Cannicattini” si trova nel diploma di fondazione del monastero di S. -

AECAA8753.23072020.Pdf

Albi definitivi dei Giudici popolari di secondo grado. Corte d'Assise d'Appello di Palermo. Anno di aggiornamento 2019. Albi Definitivi L.287/51. - biennio 2020-2021 N. P.N. COGNOME NOME DATA NASC. COMUNE NASCITA COMUNE RESIDENZA CAUSALE ESCL. 1 Abate Antonino 10/03/1980 ALCAMO ALCAMO 2 Abate Antonino 27/12/1968 CASTELVETRANO MONTEVAGO 3 Abate Enza 12/08/1971 ERICE VITA 4 Abate Enza Maria 10/05/1959 ALCAMO ALCAMO 5 Abate Enzamaria 16/03/1965 CAMPOBELLO DI MAZARA GIBELLINA 6 Abate Franca Maria 29/08/1969 TORONTO ERICE 7 Abate Francesca 04/11/1957 GIBELLINA GIBELLINA 8 Abate Gisella 19/06/1976 SCIACCA SANTA MARGHERITA DI BELICE 9 Abate Giuseppe 03/04/1978 ERICE VITA 10 Abate Giuseppe 28/12/1974 MAZARA DEL VALLO MAZARA DEL VALLO 11 Abate Lucia Maria 05/03/1959 TRAPANI TRAPANI 12 Abate Maria Concetta 05/08/1956 PALERMO TRAPANI 13 Abate Maria Pia 24/01/1960 ALCAMO ALCAMO 14 Abate Provvidenza 27/06/1978 MENFI SANTA MARGHERITA DI BELICE 15 Abate Salvatore 26/12/1964 TRAPANI TRAPANI 16 Abate Valeria 28/10/1980 ERICE PACECO 17 Abate Vincenza 24/01/1978 SALEMI VITA 18 Abate Vincenzo 13/06/1968 VITA TRAPANI 19 Abbate Domenico 23/10/1959 PALERMO LASCARI 20 Abbate Giovanna 31/08/1973 PALERMO CASTELBUONO 21 Abbate Giuseppe 19/04/1975 PALERMO MONREALE 22 Abbate Luigi 17/10/1958 TRIPOLI FAVIGNANA 23 Abbate Michele 20/07/1976 PALERMO MONREALE 24 Abbate Prassede 26/05/1965 PALERMO ALTAVILLA MILICIA 25 Abbate Vera 11/08/1969 PALERMO CINISI 26 Abbate Vincenza 03/07/1956 BAGHERIA BAGHERIA 27 Abbelli Maria Francesca 12/01/1957 ALTOFONTE ALTOFONTE 28 Abbinanti Domenico 27/02/1960 CIMINNA CIMINNA 29 Abbita Giacometta 25/11/1960 TRAPANI TRAPANI 30 Abbonato Valentina 26/11/1970 PALERMO PALERMO 31 Abbrescia Anna Maria 26/04/1958 PALERMO PALERMO 32 Abbruzzo Angelo 24/01/1959 SCIACCA CALTABELLOTTA 33 Abbruzzo Antonino 13/10/1954 CALTABELLOTTA LUCCA SICULA 34 Abbruzzo Erminia 09/08/1969 PALERMO PALERMO Albi definitivi dei Giudici popolari di secondo grado. -

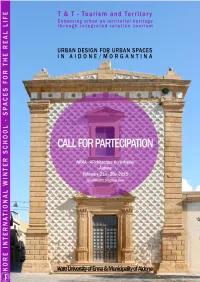

Call for Partecipation.Pdf

The Faculty of Engineering and Architecture at the ARKA Lab in Aidone offers the opportunity of a full- time research and didactic experience in enhancing urban & territorial heritage through Integrated Relational Tourism. An activity focused on the issue of Urban Design for Urban Spaces in Aidone/Morgantina as an opportunity aimed to improve the quality of life so as the local economic development for the communities of the inland rural areas. The Kore International Winter School 2015, represents a continuous of activities as interviews and meetings, workshops and expositions, lectures and site visits that, through 8 full days of common work, should explore problems and hopefully propose a range of visions for the future of the city and of the hinterland of Aidone-Morgantina and its heritage. The Kore International Winter School 2015 includes field trips and guided visits to the study site of Aidone and Morgantina, Piazza Armerina and Villa del Casale, Enna and Pergusa areas as well as social and cultural events. The School activities are articulated on three structural goals, which are: - the activity of scientific and applied Research, implicit in the proposed innovative approach as in the chosen application field; - the integrated project implementation Scenarios, as expected design results by the workshop; - the Training for new needed professionals, important to manage the transition to a different development model from the current one. Official and work languages Official language: English (for meetings, lectures, exibitions, etc.) Work languages: Arabic and Italian (for any other informal relationships!) Short Presentation The Winter School aims to promote a trans-disciplinary and international approach that encourages the development of skills and knowledge in the field of Integrated Tourism managed by the territory through its local actors and resources. -

Attitudes Towards the Safeguarding of Minority Languages and Dialects in Modern Italy

ATTITUDES TOWARDS THE SAFEGUARDING OF MINORITY LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS IN MODERN ITALY: The Cases of Sardinia and Sicily Maria Chiara La Sala Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Department of Italian September 2004 This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to assess attitudes of speakers towards their local or regional variety. Research in the field of sociolinguistics has shown that factors such as gender, age, place of residence, and social status affect linguistic behaviour and perception of local and regional varieties. This thesis consists of three main parts. In the first part the concept of language, minority language, and dialect is discussed; in the second part the official position towards local or regional varieties in Europe and in Italy is considered; in the third part attitudes of speakers towards actions aimed at safeguarding their local or regional varieties are analyzed. The conclusion offers a comparison of the results of the surveys and a discussion on how things may develop in the future. This thesis is carried out within the framework of the discipline of sociolinguistics. ii DEDICATION Ai miei figli Youcef e Amil che mi hanno distolto