Approaches to Measure the Wider Economic Impacts of High-Speed Rail and Experiences from Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ballastless Track on High-Speed Lines a Guarantee for Travel Savety And

Ballastless track on high-speed lines A guarantee for travel savety and comfort Prologue High–speed rail travel, as a fast connection between high-density population areas and as an alternative to frequently-overloaded air connections with an uncertain future, is gaining increasingly in significance all over the world. In the face of growing traffic density, critical views of life-cycle costs and significantly increa- sed requirements of the availability of railway tracks, there is an increasing demand for track systems which have a long lifetime, low service and maintenance costs and which also guarantee tra- vel safety and comfort. Ballastless tracks (BLT) have numerous advantages over the tradi- tional ballasted track, because of markedly reduced maintenance costs, longer duration of use, improved precision of the running track and the resultant quiet vehicle running. High speed and ballast The nature of the route requirements is changing, as a result of an increase in travel speed or axle loads. The load transported creates inertial forces and the particular more-frequent faults ari- sing from the rolling process are increasing dramatically. Altered deformation mechanisms with dynamic stimulation can result in major grain shifts during piling-up of ballast, which result in con- siderable impairment of the ballasted track and are responsible for uneven creeping and track displacement in the ballast bed. In addition, the track ballast stones are sucked up by vehicles at very high speeds (flying ballast) and may damage them. De- spite the choice of harder types of stone for ballast in high-speed traffic, maintenance costs are considerably higher. -

DB Netz AG Network Statement 2016 Valid from 14 April 2015 DB Netz

DB Netz AG Network Statement 2016 valid from 14 April 2015 DB Netz AG Headquarters I.NMN Version control Date Modification 12.12.2014 Amendment of Network Statement 2015 as at 12 December 2014 (Publication of the Network Statement 2016) Inclusion of detailed information in sections 1.9 ff and 4.2.5 ff due to 14.10.2015 commissioning of rail freight corridors Sandinavian-Mediterranean and North Sea-Balitc. Addition of connection to Port of Hamburg (Hohe Schaar) in section 13.12.2015 3.3.2.5 Printed by DB Netz AG Editors Principles of Network Access/Regulation (I.NMN) Theodor-Heuss-Allee 7 60486 Frankfurt am Main Picture credits Front page photo: Bildschön, Silvia Bunke Copyright: Deutsche Bahn AG Contents Version control 3 List of Annexes 7 1 GENERAL INFORMATION 9 1.1 Introduction 9 1.2 Purpose 9 1.3 Legal basis 9 1.4 Legal framework of the Network Statement 9 1.5 Structure of the Network Statement 10 1.6 Term of and amendments to the Network Statement 10 1.7 Publication and opportunity to respond 11 1.8 Contacts at DB Netz AG 11 1.9 Rail freight corridors 12 1.10 RNE and international cooperation between DB Netz AG and other RIUs 14 1.11 List of abbreviations 15 2 CONDITIONS OF ACCESS 16 2.1 Introduction 16 2.2 General conditions of access to the railway infrastructure 16 2.3 Types of agreement 17 2.4 Regulations and additional provisions 17 2.5 Special consignments 19 2.6 Transportation of hazardous goods 19 2.7 Requirements for the rolling stock 19 2.8 Requirements for the staff of the AP or the involved RU 20 2.9 Special conditions -

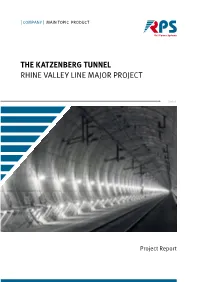

Project Report Katzenberg Tunnel

[ COMPANY ] MAIN TOPIC PRODUCT THE KATZENBERG TUNNEL RHINE VALLEY LINE MAJOR PROJECT English Dachthema Project Report 2 The LATEST SYSTEMS FOR Speed AND SAFETY IN The KATZENBERG TUNNEL The Rhine Valley line – A major project of As the expansion work in the two tunnels progressed, Deutsche Bahn AG Rail Power Systems was able to take on two additional sub-projects: The Rhine Valley line, one of the most heavily travelled lines in the DB network, is a key line for north-south con- • The contract for the planning, supply, assembly and nections for passenger traffic and the transport of goods. commissioning of the electrotechnical equipment for The complete four-track construction and expansion of the the 50 Hz power supply and tunnel safety lighting. line between Karlsruhe and Basel will optimise railway traffic in the region by 2020. • The delivery and installation of long-welded rails for the structural completion of the track systems in the Katzenberg Tunnel interface west and east tunnels. The new Katzenberg Tunnel between Bellingen and Efringen-Kirchen has significantly increased capacities and the maximum line speed of the Rhine Valley line con- nection. The high-speed overhead contact line in the two parallel, single-track tunnels enables transit speeds of up to 250 km/h, enabling a distance of 9 385 metres to be travelled in 2 minutes and 15 seconds. The connection of the complete, expanded tunnel to the Rhine Valley line took place on schedule in December 2012. Overhead contact line, 50 Hz power supply and track systems: three tasks for Rail Power Systems In the scope of this major project, Rail Power Systems Germany was assigned three central technical tasks. -

Trend Analysis of Long Tunnels Worldwide

Trend Analysis of Long Tunnels Worldwide MTI Report WP 12-09 MINETA TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE The Mineta Transportation Institute (MTI) was established by Congress in 1991 as part of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Equity Act (ISTEA) and was reauthorized under the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st century (TEA-21). MTI then successfully competed to be named a Tier 1 Center in 2002 and 2006 in the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU). Most recently, MTI successfully competed in the Surface Transportation Extension Act of 2011 to be named a Tier 1 Transit-Focused University Transportation Center. The Institute is funded by Congress through the United States Department of Transportation’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology (OST-R), University Transportation Centers Program, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), and by private grants and donations. The Institute receives oversight from an internationally respected Board of Trustees whose members represent all major surface transportation modes. MTI’s focus on policy and management resulted from a Board assessment of the industry’s unmet needs and led directly to the choice of the San José State University College of Business as the Institute’s home. The Board provides policy direction, assists with needs assessment, and connects the Institute and its programs with the international transportation community. MTI’s transportation policy work is centered on three primary responsibilities: Research MTI works to provide policy-oriented research for all levels of Department of Transportation, MTI delivers its classes over government and the private sector to foster the development a state-of-the-art videoconference network throughout of optimum surface transportation systems. -

Railways 01/2016

THE DB CARGO CUSTOMER MAGAZINE NO. 01 | 16 FULL SPEED INTO THE FUTURE Europe’s largest rail freight company undergoes restructuring. Page 08 THE INDUSTRIAL NATION’S PULSE BENELUX AND BUSTO 100 PER CENT PROMOTION On board the gypsum Expanding transport Logistics for a train to Hamburg operations to Italy discount retailer Page 16 Page 38 Page 42 EDITORIAL WE NEED A RAIL NETWORK WITH BRIGHT PROSPECTS The company is standing at a crossroads. Plummeting diesel prices, high energy taxes, politically “ It’s remarkable that Bremer regulative guidelines and rising costs are putting us under pressure. We have to ask ourselves whether includes rail on multiple levels we want to remain Europe’s leading rail freight company. at the same time.” Do wewant to offer our customers better quality ANGELA WESTFAHL, KEY ACCOUNT MANAGER, through a continuously reliable network? The answer is DB CARGO a resounding yes! Industry and trade need a capable and efficient rail freight transport system. We need a railway network that can operate fairly and offer its staff and customers good prospects for the future. With our comprehensive “Zukunft Bahn” programme, this is exactly our starting point and we are fundamentally reorganising ourselves with a new business model. We at DB Cargo and our customers in the world of business are convinced that Germany and Europe need an efficient, profitable rail freight transport sector. STABLE GROUND This is the aim of the new management team at DB Cargo – and this is the aim of our employees Haindl across Europe. tuttgart 21 is not only a transport concept is being erected on a 185,000 square metres TRANSA Spedition GmbH is responsible tions, ceiling and wall panels, as well as Roman Roman I look forward to some engaging conversations with you! S that affects the whole of southern Ger- plot and should be completed by November for the transhipment of the backfill soil in , girders and pillars, all of which have to be many, it is also an enormous building site. -

Promoting Intermodal Connectivity at California's High-Speed Rail Stations

MTI Funded by U.S. Department of Services Transit Census California of Water 2012 Transportation and California Promoting Intermodal Department of Transportation Connectivity at California’s High-Speed Rail Stations MTI ReportMTI 12-02 MTI Report 12-47 December 2012 MINETA TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE MTI FOUNDER Hon. Norman Y. Mineta The Mineta Transportation Institute (MTI) was established by Congress in 1991 as part of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Equity Act (ISTEA) and was reauthorized under the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st century (TEA-21). MTI then successfully MTI BOARD OF TRUSTEES competed to be named a Tier 1 Center in 2002 and 2006 in the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU). Most recently, MTI successfully competed in the Surface Transportation Extension Act of 2011 to Founder, Honorable Norman Joseph Boardman (Ex-Officio) Diane Woodend Jones (TE 2016) Michael Townes* (TE 2017) be named a Tier 1 Transit-Focused University Transportation Center. The Institute is funded by Congress through the United States Mineta (Ex-Officio) Chief Executive Officer Principal and Chair of Board Senior Vice President Department of Transportation’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology (OST-R), University Transportation Secretary (ret.), US Department of Amtrak Lea+Elliot, Inc. Transit Sector, HNTB Transportation Centers Program, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), and by private grants and donations. Vice Chair Anne Canby (TE 2017) Will Kempton (TE 2016) Bud Wright (Ex-Officio) Hill & Knowlton, Inc. Director Executive Director Executive Director OneRail Coalition Transportation California American Association of State The Institute receives oversight from an internationally respected Board of Trustees whose members represent all major surface Honorary Chair, Honorable Bill Highway and Transportation Officials transportation modes. -

Reference List Geotechnical Instruments

Reference List Chapter: 1.3 Page No.: 1 Geotechnical Instruments Number of Pages: 28 Aachen, Industrial Park Kohlscheid, Germany Hole deviation measurements with inclinometer in directional drillings to search for old mining shafts (2001-04); Client: Schützeichel GmbH & Co. KG Aalen, Section for Heavy Road Vehicles, Germany Installation of interstitial pressure transducers and horizontal inclinometers in measuring sections of Charlotten- and Bahnhofstreet (section for heavy vehi- cles) (2003); Client: Terrasond GmbH & Co. KG Aalen – Wasseralfingen, Germany Execution of sliding deformeter measurements in a workshop of the machine factory ALFING Kessler (2017); Client: ALFING Kessler ABS/NBS – New Railway Line Karlsruhe – Basel, Rastatt Tunnel, Germany Execution of borehole jack tests with Ettlinger borehole jack, delivery and in- stallation of pneumatic pore water pressure transducers (2012); Client: Arge Tunnel Rastatt (Terrasond GmbH & Co. KG, Drillexpert GmbH) ABS/NBS – New Railway Line Karlsruhe – Basel, Schliengener Vineyard, Germany Instrumentation and operation of a data acquisition unit with alarm function for the anchor load cells of the bored pile wall, provision of the measuring re- sults on the internet (2012-15); Client: geon GmbH, DB Netz AG ABS/NBS – New Railway Line Stuttgart – Augsburg, NBS - New Railway Line Wendlingen – Ulm, Germany Installation of Trivec measuring tubes (2003); Client: Arge Aufschluss Albaufstieg (Geomechanik, H. Anger’s Söhne, Etschel + Meyer) ABS/NBS – New Railway Line Stuttgart – Augsburg, NBS PA 2.2, Germany Delivery and installation of electric pore water pressure transducers with electronic data loggers (2015); Client: Terrasond GmbH & Co. KG, Glötzl GmbH ABS/NBS – New Railway Line Stuttgart – Augsburg, NBS New Railway Line Wendlingen – Ulm, PFA 2.1, Germany Installation of combined inclinometer/sliding deformeter measuring tubes and pore water pressure transducers (2003 and 2009, 2010); Client: Arge PFA 2.1 Albvorland (Terrasond, Waschek, Menning) Date: 2019-01-31 Geotechnisches Ingenieurbüro Prof. -

Approaches to Measure the Wider Economic Impacts of High-Speed Rail and Experiences from Europe

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Rothengatter, Werner Working Paper Approaches to measure the wider economic impacts of high-speed rail and experiences from Europe ADBI Working Paper Series, No. 946 Provided in Cooperation with: Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), Tokyo Suggested Citation: Rothengatter, Werner (2019) : Approaches to measure the wider economic impacts of high-speed rail and experiences from Europe, ADBI Working Paper Series, No. 946, Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), Tokyo This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/222713 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/igo/ www.econstor.eu ADBI Working Paper Series APPROACHES TO MEASURE THE WIDER ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF HIGH-SPEED RAIL AND EXPERIENCES FROM EUROPE Werner Rothengatter No. -

This Information Is from the Internet Pages of the Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Housing

This information is from the internet pages of the Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Housing. Please read the disclaimer at http://www.bmvbw.de/English-Content-.454.15820/Website-publication-terms-and-conditions.htm Laying the foundations for the future of mobility in Germany Federal Transport Infrastructure Plan 2003 Federal Transport Infrastructure Plan 2003: Federal Government decision of 2 July 2003 The “Federal Railway Infrastructure” section is also the basis for the draft of a First Act amending the Federal Railway Infrastructure Upgrading Act The “Federal Trunk Roads” section is also the basis for the draft of a Fifth Act amending the Federal Trunk Road Upgrading Act – II – Publication data Published by Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Housing, Berlin Website http://www.bmvbw.de Editorial team Federal Transport Infrastructure Planning Project Group Cartography Federal railway infrastructure DB Netz AG, Frankfurt am Main Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning, Bonn Federal trunk roads SSP Consult Beratende Ingenieure GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach Federal waterways Fachstelle für Geoinformationen Süd, Regensburg Cover design Adler & Schmidt GmbH Kommunikations-Design, Berlin Printed by The Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Housing’s printers, Bonn As at July 2003 This brochure is part of the public relations work of the Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Housing. It is issued free of charge and may not be sold. It must not be used for canvassing during election campaigns. Ir- respective of when and how the brochure has reached the recipi- ent and the number of copies he has received, it must not be used in a way that could suggest that the Federal Government was tak- ing sides in favour of individual groups, even if no election is due to be held in the near future. -

Taskload Report Outline

U.S. Department of Transportation High-Speed Rail Aerodynamic Assessment and Federal Railroad Mitigation Report Administration Office of Research, Development, and Technologyh Washington, DC 20590 DOT/FRA/ORD-15/40 Final Report December 2015 NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Government, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government. The United States Government assumes no liability for the content or use of the material contained in this document. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. -

DB Netz AG Network Statement 2018 Valid from 10.12.2017

DB Netz AG Network Statement 2018 valid from 10.12.2017 DB Netz AG Headquarters I.NMN Version control Date Modification 11.12.2016 Amendment of Network Statement 2017 as at 11. December 2016 (Publication of the Network Statement 2018) 06.02.2017 Amendment of Network Statement 2018 due to decision of the Fed- eral Network Agency (BNetzA) to the application of DB Netz AG for approval of the charging principles and charges for the provision of the minimum access package with effect from 10. December 2017 (TPS 2018) Printed by DB Netz AG Editors Principles of Network Access/Regulation (I.NMN) Theodor-Heuss-Allee 7 60486 Frankfurt am Main Picture credits Front page photo: Urheber: Volker Emersleben Copyright: Deutsche Bahn AG Network Statement 2018, editorial status 06.02.2017 2 Notes 1. Pending court proceedings regarding prohibitions of individual clauses The following clauses may still be modified due to court proceedings:. Section 2.9.8.3 The Federal Network Agency (BNetzA) rejected the intended modification in section 2.9.8.3 sentence 2 lit. c) of the Network Statement 2018 with its decision of 18 Novem- ber 2016 – BK 10-16-0009_Z, namely the modification to use the word “material” in rela- tion to contractual duties. The rejection also covers the addition in brackets, which in- cludes an abstract legal definition of the material contractual duty. If the rejection should be qualified as unlawful as a result of court proceedings, section 2.9.8.3 sentence 2 lit. c) would read as follows: „only for damage resulting from a non-inconsiderable -

Tunnelling Credentials Tunnel Segments, Sprayed Concrete, Grouts and Mortars What We Can Do Hanson UK, a Capable Business

Hanson UK Tunnelling Credentials Tunnel segments, sprayed concrete, grouts and mortars What we can do Hanson UK, a capable business Hanson UK is part of the HeidelbergCement Group, Hanson Concrete is one of the UK’s biggest suppliers Hanson Building Products is split into three business employing 53,000 people across five continents. of ready-mixed concrete from a network of more than units. Material Products produces clay bricks, Thermalite HeidelbergCement is the global leader in aggregates 200 fixed and site-based plants. (aircrete) and aggregate blocks. Design Solutions and a leader in cement, concrete and heavy building manufactures bespoke precast concrete products and products (brick, block and precast concrete). Hanson Asphalt and Contracting supplies and includes Formpave, a specialist in sustainable urban lays asphalt for road surfacing and provides a range drainage systems and Bath and Portland stone, a leading Hanson UK is split into five business lines offering of infrastructure services. Its civil engineering division supplier of natural stone masonry. Build Solutions draws the broadest range of products and services in the specialises in the construction of wind farms and on the skills within Hanson Structherm, manufacturers heavy building products market. waste-to-energy plants. of structural cladding systems and experts in new build and refurbishment products, and Irvine-Whitlock, a Hanson Aggregates produces sand, gravel and crushed Hanson Cement is a leading manufacturer of Portland specialist brick and block laying contractor. rock from over 62 quarries in England and Wales and cement, both in bulk and in bags, and produces ground includes Hanson Aggregates Marine, Europe’s largest granulated blastfurnace slag (GGBS) under the brand producer of marine-dredged sand and gravel.