Risk and Combat Compensation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Class Schedule

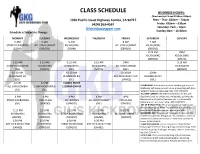

CLASS SCHEDULE BUSINESS HOURS: (Wednesdays Closed 1130am-330pm) 1930 Pacific Coast Highway Lomita, CA 90717 Mon – Thur: 830am – 730pm (424) 263-4567 Friday: 830am – 630pm Saturday: 7am – 12pm Gilskickboxinggym.com Sunday: 8am – 10:30am Schedule is Subject to Change. MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 6 AM 6 AM 6 AM 6 AM 7 AM STRAP KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KICKBOXING (JOHN) (SERGIO) (JOHN) (SERGIO) (SERGIO) 8:15 AM 8AM KICKBOXING KICKBOXING (SERGIO) (MAYA) 9:15 AM 9:15 AM 9:15 AM 9:15 AM 9AM 9:15 AM STRAP KICKBOXING KICKBOXING KICKBOXING KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KICKBOXING (GIL) (MAYA) (GIL) (MAYA) (GIL) (SERGIO) 10:30 AM 10:30 AM 10:30AM 10AM BEGINNERS BJJ BEGINNERS BJJ ART OF 8 MUAY THAI BEGINNERS BJJ (GIL) (GIL) (JAMES) (GIL) 12 PM 12 PM CLOSED FROM KICKBOXING: A 60-minute workout combining a series of ALL GYM COMBAT STRAP KICKBOXING 1130AM-330PM kickboxing techniques you will do on a heavy bag with body (Gil) (GIL) weight muscle endurance exercises. (NO CONTACT) ALL GYM COMBAT: We use the whole gym for this one. 4 PM 4 PM 4 PM 4 PM 4PM Equipment such as battle ropes, Kettlebells, agility ladder, Bungee cable, Grappling Dummies, etc. combined with STRAP KICKBOXING KIDS CLASS KICKBOXING ALL GYM COMBAT KIDS CLASS Kickboxing to train like a fighter. (NO CONTACT) (GIL) (SERGIO) (SERGIO) (GIL) (SERGIO) ART OF 8 MUAY THAI: This Class focuses on teaching you the fundamentals of Muay Thai Kickboxing. You will learn 5:15 PM 5:15 PM 5:15 PM 5:15 PM 5:15PM how to hold Thai pads and gain real striking skills. -

The Death of Dueling Wade Ellett

59 60 The Death of Dueling feuds, and a chivalric code of honor emphasizing virtue.6 Eventually this code of honor evolved into the upper class and nobility’s theory of courtesy and the idea of the “gentleman”. This resulted in the adoption of one-on-one combat to settle affairs in 7 the sixteenth century. The duel of honor, as recognized from entertainment media, was based primarily on the Italian Wade Ellett Renaissance idea of the gentleman and arrived in England in the 1570s.8 The practice was welcomed by the upper classes, who had Violence in some form or another has probably always long been awaiting a method to solve disputes. But the warm existed. Civilization did not end violence, it merely provided a reception was not shared by royalty, and Queen Elizabeth I framework to ritualize and institutionalize violent acts. Once outlawed the judicial duel in 1571.9 Her attempts to remove the civilized, ritual violence became almost entirely a man’s realm.1 practice from England failed and dueling quickly gained Ritual violence took many forms; but, without a doubt, one of the popularity.10 most romanticized was the duel. Dueling differed from wartime Dueling thrived in England for nearly three centuries; violence and barroom brawls because dueling placed two however, the practice eventually came to an end in 1852, when the opponents, almost always of similar social class, against one last recorded English duel was fought. There were many another in a highly stylized form of combat.2 Fisticuffs and war contributing factors to the practice’s end. -

World Combat Games Brochure

Table of Contents 4 5 6 What is GAISF? What are the World Roles and Combat Games? responsibilities 7 8 10 Attribution Culture, ceremonies Media promotion process and festival events, and production and legacy 12 13 14 List of sports Venue Aikido at the World setup Armwrestling Combat Games Boxing 15 16 17 Judo Kendo Muaythai Ju-jitsu Kickboxing Sambo Karate Savate 18 19 Sumo Wrestling Taekwondo Wushu 4 WORLD COMBAT GAMES WORLD COMBAT GAMES 5 What is GAISF? What are the World Combat Games? The united voice of sports - protecting the interests of International A breathtaking event, showcasing Federations the world’s best martial arts and GAISF is the Global Association of International Founded in 1967, GAISF is a key pillar of the combat sports Sports Federations, an umbrella body composed wider sports movement and acts as the voice of autonomous and independent International for its 125 Members, Associate Members and Sports Federations, and other international sport observers, which include both Olympic and non- and event related organisations. Olympic sports organisations. THE BENEFITS OF THE NUMBERS OF HOSTING THE WORLD THE GAMES GAISF MULTISPORT GAMES COMBAT GAMES Up to Since 2010, GAISF has successfully delivered GAISF serves as the conduit between ■ Bring sport to life in your city multisport games for combat sports and martial International Sports Federations and host cities, ■ Provide worldwide multi-channel media exposure 35 disciplines arts, mind games and urban orientated sports. bringing benefits to both with a series of right- ■ Feature the world’s best athletes sized events that best consider the needs and ■ Establish a perfect bridge between elite sport and Approximately resources of all involved. -

1St Degree Combat Maneuvers

1st Degree Combat provoked, you expend one piece of ammunition or thrown weapon. Maneuvers Doubleshot (1 point) Adamant Mountain Bonus Action—The next ranged weapon attack you make uses two missiles instead of Heavy Combat Stance (1 point) one. You make this attack with minor disadvantage. On a hit, you deal an Stance—On each of your turns, you gain additional damage die. minor advantage on your first melee weapon attack roll using a weapon with the Heavy property. Farshot Combat Stance (1 point) Stance—When you are wielding a ranged Heavy Swing (1 point) weapon, increase its normal range by 10 feet and long range by 30 feet. Reaction—When you hit with a melee weapon attack using a weapon with the Heavy property, you can use your reaction to Guarded Draw (1 point) make an additional melee weapon attack Bonus Action—Being within 5 feet of a against a second creature that is also within hostile creature who can see you and who your reach. You have minor disadvantage on isn’t incapacitated does not give you this additional attack. disadvantage when making a ranged weapon attack. In addition, when an adjacent hostile Lean Into It (1 point) creature that you can see moves 5 feet or more away from you, you can use your Technique—Until the start of your next turn, reaction to make a ranged weapon attack you deal an extra 1d4 damage whenever you against it. hit with a weapon attack using a weapon that has the Heavy property. Mirror's Glint Mountain’s Might (2 points) Intuitive Combat Stance (1 point) Bonus Action—You regain hit points equal to 1d6 + your proficiency bonus + your Stance—You gain minor advantage on Constitution modifier (minimum 0). -

Hand to Hand Combat

*FM 21-150 i FM 21-150 ii FM 21-150 iii FM 21-150 Preface This field manual contains information and guidance pertaining to rifle-bayonet fighting and hand-to-hand combat. The hand-to-hand combat portion of this manual is divided into basic and advanced training. The techniques are applied as intuitive patterns of natural movement but are initially studied according to range. Therefore, the basic principles for fighting in each range are discussed. However, for ease of learning they are studied in reverse order as they would be encountered in a combat engagement. This manual serves as a guide for instructors, trainers, and soldiers in the art of instinctive rifle-bayonet fighting. The proponent for this publication is the United States Army Infantry School. Comments and recommendations must be submitted on DA Form 2028 (Recommended Changes to Publications and Blank Forms) directly to Commandant, United States Army Infantry School, ATTN: ATSH-RB, Fort Benning, GA, 31905-5430. Unless this publication states otherwise, masculine nouns and pronouns do not refer exclusively to men. iv CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Hand-to-hand combat is an engagement between two or more persons in an empty-handed struggle or with handheld weapons such as knives, sticks, and rifles with bayonets. These fighting arts are essential military skills. Projectile weapons may be lost or broken, or they may fail to fire. When friendly and enemy forces become so intermingled that firearms and grenades are not practical, hand-to-hand combat skills become vital assets. 1-1. PURPOSE OF COMBATIVES TRAINING Today’s battlefield scenarios may require silent elimination of the enemy. -

The Use of Functional Training – Crossfit Methods to Improve the Level of Special Training of Athletes Who Specialize in Combat Sambo

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Siberian Federal University Digital Repository The use of functional training – crossfit methods to improve the level of special training of athletes who specialize in combat sambo. ALEKSANDER OSIPOV1, 2, MIKHAIL KUDRYAVTSEV1, 3,4,5, KONSTANTIN GATILOV1, TATYANA ZHAVNER1,4, YULYA KLIMUK1, EKATERINA PONOMAREVA1, ANNA VAPAEVA1, POLINA FEDOROVA1, EVGENY GAPPEL4, ALEKSANDER KARNAUKHOV4 1Siberian Federal University, 2Krasnoyarsk State Medical University named after professor V.F. Voyno- Yasenetsky, 3Reshetnev Siberian State University of Science and Technology, 4Krasnoyarsk State Pedagogical University named after V. P. Astafiev, 5Siberian Law Institute of the Ministry of Internal Affair of Russia, Krasnoyarsk, RUSSIA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The article is devoted to the search for effective methods of training effects on athletes specializing in combat sambo. It was revealed that the main criterion determining the success of combat sambo wrestlers in the competitive activity will be the level of their special training. Moreover, this training includes special endurance of athletes, active dynamics of competitive contests and the speed of recovery of fighters after intense training and competitive loads. Besides, to increase the level of special endurance combat sambo wrestlers significantly it was suggested to include in the training process of combat athletes the method of intensive functional training - crossfit. In a year of studies the tests on the evaluation of the level of recovery of combat athletes after a specific load showed that the athletes using the training method - crossfit in their training sessions demonstrated significantly (P <0.05) the best recovery time after the load than the wrestlers who did not use this technique. -

Mixed Martial Arts Rules for Amateur Competition Table of Contents 1

MIXED MARTIAL ARTS RULES FOR AMATEUR COMPETITION TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SCOPE Page 2 2. VISION Page 2 3. WHAT IS THE IMMAF Page 2 4. What is the UMMAF Page 3 5. AUTHORITY Page 3 6. DEFINITIONS Page 3 7. AMATEUR STATUS Page 5 8. PROMOTERS & REQUIREMENTS Page 5 9. PROMOTERS INSURANCE Page 7 10. PHYSICIANS AND EMT’S Page 7 11. WEIGN-INS & WEIGHT DIVISIONS Page 8 12. COMPETITORS APPEARANCE& REQUIREMENTS Page 9 13. COMPETITOR’s MEDICAL TESTING Page 10 14. MATCHMAKING APPROVAL Page 11 15. BOUTS, CONTESTS & ROUNDS Page 11 16. SUSPENSIONS AND REST PERIODS Page 12 17. ADMINISTRATION & USE OF DRUGS Page 13 18. JURISDICTION,ROUNDS, STOPPING THE CONTEST Page 13 19. COMPETITOR’s REGISTRATION & EQUIPMENT Page 14 20. COMPETITON AREA Page 16 21. FOULS Page 17 22. FORBIDDEN TECHNIQUES Page 18 23. OFFICIALS Page 18 24. REFEREES Page 19 25. FOUL PROCEDURES Page 21 26. WARNINGS Page 21 27. STOPPING THE CONTEST Page 22 28. JUDGING TYPES OF CONTEST RESULTS Page 22 29. SCORING TECHNIQUES Page 23 30. CHANGE OF DECISION Page 24 31. ANNOUNCING THE RESULTS Page 24 32. PROTESTS Page 25 33. ADDENDUMS Page 26 PROTOCOL FOR COMPETITOR CORNERS ROLE OF THE INSPECTORS MEDICAL HISTORY ANNUAL PHYSICAL OPTHTHALMOLOGIC EXAM PROTOCOL FOR RINGSIDE EMERGENCY PERSONNEL PRE & POST –BOUT MEDICAL EXAM 1 SCOPE: Amateur Mixed Martial Arts [MMA] competition shall provide participants new to the sport of MMA the needed experience required in order to progress through to a possible career within the sport. The sole purpose of Amateur MMA is to provide the safest possible environment for amateur competitors to train and gain the required experience and knowledge under directed pathways allowing them to compete under the confines of the rules set out within this document. -

A Systematic Review of Combat Sport Literature

Sports Med DOI 10.1007/s40279-016-0493-1 SYSTEMATIC REVIEW Towards a Determination of the Physiological Characteristics Distinguishing Successful Mixed Martial Arts Athletes: A Systematic Review of Combat Sport Literature 1 2 1,3 1 Lachlan P. James • G. Gregory Haff • Vincent G. Kelly • Emma M. Beckman Ó Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 Abstract distinguish superior competitors, with a view to defining Background Mixed martial arts (MMA) is a combat sport the optimal physiological profile for higher-level MMA underpinned by techniques from other combat disciplines, performance. Furthermore, this article will explore the in addition to strategies unique to the sport itself. These differences in these capabilities between grappling- and sports can be divided into two distinct categories (grap- striking-based combat sports in the context of MMA. pling or striking) based on differing technical demands. Methods A literature search was undertaken via PubMed, Uniquely, MMA combines both methods of combat and Web of Science, SportDiscus and Google Scholar. The therefore appears to be physiologically complex requiring a following sports were included for systematic review based spectrum of mechanical and metabolic qualities to drive on their relevance to MMA: mixed martial arts, boxing, performance. However, little is known about the physio- Brazilian jiu-jitsu, judo, karate, kickboxing, Muay Thai and logical characteristics that distinguish higher- from lower- wrestling. The inclusion criteria allowed studies that level MMA athletes. Such information provides guidance compared athletes of differing competition levels in the for training interventions, performance testing and talent same sport using a physiological performance measure. identification. Furthermore, while MMA incorporates Only male, adult (aged 17–40 years), able-bodied com- techniques from both grappling and striking sports, it is petitors were included. -

Spring 2012 Bucks County Aikido Journal Buckscountyaikido.Com•802 New Galena Rd., Doylestown PA 18901•(215) 249-8462

Ensō • Issue 10, Spring 2012 Bucks County Aikido Journal BucksCountyAikido.com•802 New Galena Rd., Doylestown PA 18901•(215) 249-8462 Ha by George Lyons You may love Aikido now but you are headed for a crisis. And when yours arrives you will probably quit. So there you go. The hard news is out and you can’t say I didn’t tell you so. You might say, “I’m ready… bring it on.” But here’s the thing; your crisis will be uniquely yours, tailor made and targeted right at your blind spot. Damn! If only you could learn this swim but refusing to give up. Add to feel that way. Suffering has many without any of that. It’s such a beau- this that instead of one boat there is forms and when it comes as confu- tiful art, so noble and high minded, a whole fleet, some insist on rowing sion its pretty unsettling. Check in wonderful ideas to hear and think alone, while others work together, with yourself and listen. Confusion about. Embody? Even better! lots of boats, lots of ropes, lots of should not be mistaken for being The traditional way of organizing swimming… chaos! off track. There’s a difference and around this practice is so orderly. When you reach the point in your knowing what it is, is so important Lining up in straight lines, the rit- training where you see more, when as to be the central issue of our lives. uals, the forms, can give the idea things are not as simple as they used Hanging onto a trailing rope, the there is a promised land where all to be, it’s natural to long for the days idea of letting go comes to mind. -

The Reality of COMBAT!: an Analysis of Historical Memory in Broadcast Television Kaleb Q

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 5-2016 The Reality of COMBAT!: An Analysis of Historical Memory in Broadcast Television Kaleb Q. Wentz Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the Cultural History Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Military History Commons, Other History Commons, Public History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wentz, Kaleb Q., "The Reality of COMBAT!: An Analysis of Historical Memory in Broadcast Television" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 333. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/333 This Honors Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Reality of COMBAT!: An Analysis of Historical Memory in Broadcast Television By Kaleb Quinn Wentz An Undergraduate Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Midway Honors Scholars Program Honors College ___________________________________________ Dr. Stephen Fritz, Thesis Mentor Date ___________________________________________ Dr. John Rankin, Reader Date ___________________________________________ Dr. Henry Antkiewicz, Reader Date 1 ABSTRACT This thesis is an analysis of the World War II television drama COMBAT!, which ran from 1962 to 1967, and how this program dealt with and addressed the national memory of the Second World War. Memories are fluid; they shift and adapt as time goes on. The way in which the “Good War” is remembered is subject to this same process. -

The Department of France AMERICAN LEGION

The Department of France AMERICAN LEGION DEPARTMENT COMMANDER James Settle the Post Home. Make sure your delegates have a delegates letter or they will not be allowed to vote on any motions presented. My Fellow Legionaries It is time for Post Commanders and Adjutants to start I was invited to, and attended John Wayne Post GR79's ceremony working on their proposed Awards. The Awards packets are event on 11 January 2015, due to the Awards Chairman, Comrade Brown not later than honoring the 30th anniversary of 18 April 2015. the Awards Committee will meet on the 25th three soldiers' who died in a of April 2015 in Heilbronn. If your Awards packets are completed they can be turned in during the 3rd DEC in missile mishap on 11 January 1985, Kitzingen in March. at Red Leg Waldheide Heilbronn. The ceremony was done with respect and honored those fallen warriors of the COLD WAR. On 31st of January 2015 members of GR06, along with department officers conducted a membership drive at the Kaiserslautern Post GR01 will have a farewell dinner for Vice P.X on Panzer Kaserne from 1000 till 1700 hours. The Commander Stephen Ward, on the 2nd of February 2015. membership drive was a success, and GR06 even had a few Vice Commander Ward has been reassigned to the United of their current members renew for 2015. States, and will depart Germany on or about the 8th of Important information… February 2015. Vice Commander Ward will be sorely missed within the Department of France, we thank Vice The Department Sergeant-at-Arms/POW/MIA Chairman Commander Ward for his support to the Department of Comrade Hal Rittenberg(Post GR09)had to resign due to France over the last several years, and wish him and his health reasons. -

January-February 1977, Volume XXVIII, No. 2

U N I VE R S IT Y reuiew JA N U A R Y -F E B R U A R Y 1977 The Professional Journal of the United States Ai from the editor's aerie It is with no little astonishment that we receive frequent queries from Air Force personnel asking how they might regularly receive Air University Review. Of course, the cognoscenti know that the Basis of Issue, which we reprint annually, establishes distribution to assure reasonable access for all Air Force personnel. Colonels and above as well as civil service grades GS-16-18 are authorized personal copies. All organizations down to detachment level are authorized distribution on the basis of one copy for each 20 officers. In case of organizations having fewer than 20 officers, any lesser number would qualify, including detachments with as few as one officer. The essential point to remember is that distribution is not automatically accomplished solely on the basis of your eligibility. If you are not already receiving the Review, you must establish your requirement with your servicing Publications Distribution Officer. Our published contributors are, of course, aware that they receive a complimentary subscription for one year, in addition to a cash award that is somewhat more munificent than in past years. And certainly no one is discouraged from subscribing directly to the Government Printing Office, as outlined on the inside back cover. We are presently revising the Basis of Issue with the object of increasing its availability, particularly for individuals engaged in scholarly pursuits and for noncommissioned officers. If we are successful in this revision, we promise to make it known promptly.