An Analysis of the Contemporary Arts of Zambia and Zimbabwe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

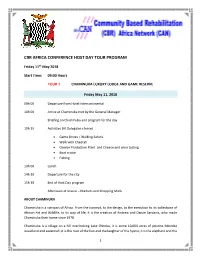

Cbr Africa Conference Host Day Tour Program

CBR AFRICA CONFERENCE HOST DAY TOUR PROGRAM Friday 11th May 2018 Start Time: 09:00 Hours TOUR 1 CHAMINUKA LUXURY LODGE AND GAME RESERVE Friday May 11, 2018 09h 00 Departure from Hotel Intercontinental 10h 00 Arrive at Chaminuka met by the General Manager Briefing on Chaminuka and program for the day 10h 15 Activities (At Delegates choice) • Game Drives / Walking Safaris • Walk with Cheetah • Cheese Production Plant and Cheese and wine tasting • Boat cruise • Fishing 13h 00 Lunch 14h 30 Departure for the city 15h 30 End of Host Day program Afternoon at leisure – Markets and Shopping Malls ABOUT CHAMINUKA Chaminuka is a synopsis of Africa. From the concept, to the design, to the execution to its collections of African Art and Wildlife, to its way of life, it is the creation of Andrew and Danae Sardanis, who made Chaminuka their home since 1978. Chaminuka is a village on a hill overlooking Lake Chitoka; it is some 10,000 acres of pristine Miombo woodland and savannah; it is the roar of the lion and the laughter of the hyena; it is the elephant and the 1 giraffe and the zebra and the eland and the sable and all the other animals of the Zambian bush; and it is the fish eagle and the kingfisher and the ibis and the egrets and the storks and the ducks and the geese and the other migratory birds that visit its lakes for rest and recuperation during their long annual sojourns from the Antarctic to the Russian steppes and back. And it is the huge private collection of contemporary African paintings and sculpture as well as traditional artefacts - more than one thousand pieces - acquired from all over Africa over a period of 50 years. -

To What Extent Was World War Two the Catalyst Or Cause of British Decolonisation?

To what extent was World War Two the catalyst or cause of British Decolonisation? Centre Number: FR042 Word Count: 3992 Words Did Britain and her colonies truly stand united for “Faith, King and Empire” in 1920, and to what extent was Second World War responsible for the collapse of this vast empire? Cover Picture: K.C. Byrde (1920). Empire of the Sun [online]. Available at: http://worldwararmageddon.blogspot.com/2010/09/empire-of-sun.html Last accessed: 27th January 2012 Table of Contents Abstract Page 2 Introduction Page 3 Investigation Page 4 – Page 12 • The War Caused Decolonisation in Page 4 – Page 7 African Colonies • The War acted as a Catalyst in an Page 7 – Page 8 international shift against Imperialism • The War Slowed down Decolonisation in Page 8 – Page 10 Malaya • The War Acted as a Catalyst with regard Page 10 – Page 11 to India • The Method of British Imperialism was Page 11 – Page 12 condemned to fail from the start. Conclusion Page 13 Bibliography Page 14 – Page 15 1 Abstract This question answered in this extended essay is “Was World War Two the catalyst or the cause of British Decolonisation.” This is achieved by analysing how the war ultimately affected the British Empire. The British presence in Africa is examined, and the motives behind African decolonisation can be attributed directly to the War. In areas such as India, once called the ‘Jewel of the British Empire,’ it’s movement towards independence had occurred decades before the outbreak of the War, which there acted merely as a Catalyst in this instance. -

Abstract Art and the Contested Ground of African Modernisms

ABSTRACT ART AND THE CONTESTED GROUND OF AFRICAN MODERNISMS By PATRICK MUMBA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER of FINE ART of RHODES UNIVERSITY November 2015 Supervisor: Tanya Poole Co-Supervisor: Prof. Ruth Simbao ABSTRACT This submission for a Masters of Fine Art consists of a thesis titled Abstract Art and the Contested Ground of African Modernisms developed as a document to support the exhibition Time in Between. The exhibition addresses the fact that nothing is permanent in life, and uses abstract paintings that reveal in-between time through an engagement with the processes of ageing and decaying. Life is always a temporary situation, an idea which I develop as Time in Between, the beginning and the ending, the young and the aged, the new and the old. In my painting practice I break down these dichotomies, questioning how abstractions engage with the relative notion of time and how this links to the processes of ageing and decaying in life. I relate this ageing process to the aesthetic process of moving from representational art to semi-abstract art, and to complete abstraction, when the object or material reaches a wholly unrecognisable stage. My practice is concerned not only with the aesthetics of these paintings but also, more importantly, with translating each specific theme into the formal qualities of abstraction. In my thesis I analyse abstraction in relation to ‘African Modernisms’ and critique the notion that African abstraction is not ‘African’ but a mere copy of Western Modernism. In response to this notion, I have used a study of abstraction to interrogate notions of so-called ‘African-ness’ or ‘Zambian-ness’, whilst simultaneously challenging the Western stereotypical view of African modern art. -

Zambia Briefing Packet

ZAMBIA PROVIDING COMMUNITY HEALTH TO POPULATIONS MOST IN NEED se P RE-FIELD BRIEFING PACKET ZAMBIA 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org ZAMBIA Country Briefing Packet Contents ABOUT THIS PACKET 3 BACKGROUND 4 EXTENDING YOUR STAY? 5 HEALTH OVERVIEW 11 OVERVIEW 14 ISSUES FACING CHILDREN IN ZAMBIA 15 Health infrastructure 15 Water supply and sanitation 16 Health status 16 NATIONAL FLAG 18 COUNTRY OVERVIEW 19 OVERVIEW 19 CLIMATE AND WEATHER 28 PEOPLE 29 GEOGRAPHy 30 RELIGION 33 POVERTY 34 CULTURE 35 SURVIVAL GUIDE 42 ETIQUETTE 42 USEFUL LOZI PHRASES 43 SAFETY 46 GOVERNMENT 47 Currency 47 CURRENT CONVERSATION RATE OF 26 MARCH, 2016 48 IMR RECOMMENDATIONS ON PERSONAL FUNDS 48 TIME IN ZAMBIA 49 EMBASSY INFORMATION 49 U.S. Embassy Lusaka 49 WEBSITES 50 !2 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org ZAMBIA Country Briefing Packet ABOUT THIS PACKET This packet has been created to serve as a resource for the IMR Zambia Medical and Dental Team. This packet is information about the country and can be read at your leisure or on the airplane. The first section of this booklet is specific to the areas we will be working near (however, not the actual clinic locations) and contains information you may want to know before the trip. The contents herein are not for distributional purposes and are intended for the use of the team and their families. Sources of the information all come from public record and documentation. You may access any of the information and more updates directly from the World Wide Web and other public sources. -

ACASA Newsletter 117, Winter 2021 Welcome from ACASA

Volume 117 | Winter 2021 ACASA Newsletter 117, Winter 2021 Welcome from ACASA From the President Dear ACASA Members, The world-wide injustices of this past year coupled with the global pandemic have affected many of our lives. This week in the United States we are celebrating Martin Luther King, Jr. Day as well as the inauguration of President-Elect Joseph Biden and Vice President-Elect Kamala Harris. It will be, in the words of another great U.S. president, “not a victory of party, but a celebration of freedom ─ symbolizing an end as well as a beginning ─ signifying renewal as well as change.” (J.F.K.’s Inaugural Address, 1961). It is this moment, ripe with potential, that we celebrate. It is not about accepting those whose actions or views we abhor, but shifting our attention to a deeper level, to, as Dr. King wrote, a "creative, redemptive goodwill for all" that has the power to bring us together by appealing to our best nature. I look forward to the coming months as we prepare to gather at our Triennial in June. The virtual format will allow us enriching experiences including interactive panels, studio, gallery, and museum walk-throughs, tributes, networking, and lively discussions that can go on long past panel completion. Our virtual conference will draw us together and inspire. In Strength and Solidarity, Peri ACASA President ACASA website From the Editor Dear ACASA Members, In my two years serving as the ACASA newsletter editor, I cannot recall receiving so many long range exhibition announcements as this time. Obviously, while museums are closed, new exhibitions never properly opened and cultural life is shut down, the energies concentrate on looking ahead. -

The Colossus of Rhodes: a Powerful Enigma

XXXXXX The Colossus of Rhodes: A Powerful Enigma BY LONE WRIEDT SØRENSEN 15 DOCUMENTING ANCIENT RHODES: ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITIONS AND RHODIAN ANTIQUITIES The Colossus of Rhodes: of the technical details concerning the construction of the Colossus. According to him the feet of the statue, A Powerful Enigma which were filled in rocks, were fixed upon a base of white marble.5 Furthermore, Johannes Malalas, a historian from Antiochia at Odessa (AD 490-575), reports in his book (ch. BY LONE WRIEDT SØRENSEN 11.18) that 312 years after its fall, during which time none of it went missing, Hadrian re-erected it on the same spot at a cost of three Centenaria of gold, the fact of which was The Colossus of Rhodes, the icon of the island, occupies inscribed on its base. a unique position from Antiquity to present times. No- The size of the statue and the fact that it was made one can claim to have found or excavated the Colossus, of bronze have particularly intrigued those who have let alone describe with certainty what it looked like, how commented on it. Using Philo’s account in De Septem Orbis it was constructed or where it was erected. Over the years Spectaculis, the sculptor Herbert Maryon proposed that for it has nonetheless been the subject of many studies based the amount of 500 talents the statue mentioned by Philo on archaeological and textual data, and it still attracts must have been constructed on the site from thin, beaten- scholarly interest – and, indeed, other kinds of interest.1 out sheets, while Haynes with reference to the same text The biography of the statue as a concept is remarkable. -

Cecil Rhodes

Table of Contents How to Use This Product . 3 Battle of Khartoum and Omdurman Map . .47–50 Introduction to Primary Sources . 5 The Battle for Sudan . .47 Battle Review. .49 Activities Using Primary Sources . 15 Battle of Khartoum and Omdurman Photographs Map . .50 Treaty of Tianjin . .15–16 Life Magazine: The White Man’s Opium Wars. .15 Burden. .51–54 In the Words of Kipling. .51 The Sepoy Rebellion . .17–18 Kipling’s Meaning . .53 The Sepoys Fight Back . .17 Life Magazine: The White Man’s In the Rubber Coils . .19–20 Burden. .54 Belgians in the Congo . .19 Social Darwinism Poster . .55–58 Emperor Meiji’s Family . .21–22 Social Darwinism. .55 Japan and the Meiji Restoration . .21 Imperialism Facts and Opinions . .57 Chinese Christian Refugees. .23–24 Social Darwinism Poster . .58 Boxer Rebellion . .23 Japanese Propaganda Handbill . .59–62 Take Your Choice . .25–26 Japanese Imperialism. .59 The United States in the Philippines . .25 Revised Viewpoint. .61 Japanese Propaganda Handbill . .62 The Panama Canal . .27–28 Imperialism in Latin America . .27 Document-Based Assessments . 63 Gandhi’s Salt March . .29–30 The Words of Mahatma Gandhi . .63 The British in India . .29 China’s Open Door . .64 Primary Sources “The White Man’s Burden”. .65 ABC for Baby Patriots. .31–34 The Suez Canal . .66 Nationalism and Imperialism. .31 Portsmouth Peace Conference . .67 ABC for the Colonized . .33 ABC for Baby Patriots. .34 Survival of the Fittest . .68 African Map . .35–38 Democratic Platform . .69 The Scramble for Africa . .35 Sun Yat-sen’s Victory . .70 Dividing Africa . -

Island Peoples Coming to Terms with Their Imperial Legacy

Fordham University Fordham Research Commons Senior Theses International Studies Winter 2-1-2021 Japan and the United Kingdom: Island Peoples Coming to Terms with their Imperial Legacy Trisha Ann Canessa Follow this and additional works at: https://research.library.fordham.edu/international_senior Part of the Politics and Social Change Commons Japan and the United Kingdom: Island Peoples Coming to Terms with their Imperial Legacy Trisha Canessa Professor Christopher Toulouse & Professor Mariko Aratani International Studies Senior Thesis December 20, 2020 1 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Methodology 6 Literature Review 9 Japanese Minzoku and Yamato-Damashii 9 UK’s Brexit 11 Japanese Case Study 13 Japanese Nationalism: The Source for Unification and Division 13 Japanese Anti-Immigration Rhetoric 16 A New Era of Diversity in Japanese Popular Culture 21 British Case Study 25 British Nationalism: The Source for Unification and Division 25 British Anti-Immigration Rhetoric 29 Backlash to Diversity in Popular British Culture 34 Discussion and Analysis 39 Appendix 45 Bibliography 53 2 Abstract Similar to the United States, other colonial nations such as Japan and the United Kingdom hold prejudicial pasts that have impacted their current social climates. In contrast to the U.S.’s long- time racial hostilities, Japan and Britain’s traditional institutions centered their nationalist campaigns with an anti-foreigner sentiment. The nationalist campaigns within Japan and Britain were prompted by their effort to re-establish their identities after the devastations of World War II. For Japan, conservatives prioritized the preservation of their cultural roots from foreign influence. For the United Kingdom, conservatives used imperial nostalgia to call for a revitalization of the height of their past. -

Kudzanai Chiurai Madness & Civilization

KUDZANAI CHIURAI MADNESS & CIVILIZATION CURATED BY CANDICE ALLISON 12 APRIL – 12 MAY 2018 GOODMAN GALLERY CAPE TOWN Kudzanai Chiurai, Madness & Civilization III, 2017 (detail) CAPE TOWN GALLERY HOURS TUESDAY–FRIDAY: 09H30–17H30 SATURDAY: 10H00–16H00 3RD FLOOR FAIRWEATHER HOUSE 176 SIR LOWRY RD, WOODSTOCK P. +27 (0)21 462 7573/4 F. +27 (0)21 462 7579 cpt@goodman–gallery.com www.goodman–gallery.com In November 2017, Kudzanai Chiurai’s first solo exhibition in his home Kudzanai Chiurai was born in Harare in 1981, where he currently lives and country, We Need New Names, went on view at the National Gallery of works. His work was the focus of two major solo surveys in 2017 including Zimbabwe. Its timing was prescient. While the country’s longstanding We Need New Names at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, Harare; and former President Robert Mugabe was being ousted through a military-led Regarding the Ease of Others at Zeitz MoCAA, Cape Town. Other solo coup, Chiurai was exhibiting his politically-driven work, which combines exhibitions have taken place at MoCADA, New York (2015); RISD Museum, art historical imagery with references from popular culture and archival Rhode Island (2015); Kulungwana Gallery, Maputo (2015); and Brixton material to explore the visual language and tropes that help construct Art Gallery, London (2003). Notable group exhibitions include In Their myths, history, and ultimately power. Own Form at Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago (2018); Ex Africa presented by Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, Belo Horizonte in Under the continued curation of Candice Allison, Madness and Civilization Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Brasília (2017-18); Africa. -

Killing Rhodes: Decolonization and Memorial Practices in Post-Apartheid South Africa

Folk Life Journal of Ethnological Studies ISSN: 0430-8778 (Print) 1759-670X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/yfol20 Killing Rhodes: decolonization and memorial practices in post-apartheid South Africa Ernst van der Wal To cite this article: Ernst van der Wal (2018): Killing Rhodes: decolonization and memorial practices in post-apartheid South Africa, Folk Life To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/04308778.2018.1502408 Published online: 06 Aug 2018. Submit your article to this journal View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=yfol20 FOLK LIFE https://doi.org/10.1080/04308778.2018.1502408 Killing Rhodes: decolonization and memorial practices in post-apartheid South Africa Ernst van der Wal Department of Visual Arts, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This article investigates the conflicted relationship that exists Decolonization; memorials; between practices of memorial commemoration and contempor- commemoration; Rhodes ary calls for the decolonization of public space. Drawing on the Must Fall example of the Rhodes Must Fall movement that originated in Cape Town, South Africa, this article demonstrates how the spati- ality of commemoration is affected by decolonizing interrogations of memorial structures. Within a postcolonial context, commem- orations of Cecil John Rhodes (1853–1902), the iconic British busi- nessman and politician who was well known for his race-based prejudices and who played such an important role in the history of South Africa, have become sites where lingering colonial and racist discourses are unearthed and explored. As such, the practices and spaces of memorialization have come under severe criticism for the distorted historical narratives they have long upheld. -

Bibliographie

1 L’ART PLASTIQUE CONTEMPORAIN DE LUBUMBASHI ET DU CONGO. SOURCES IMPRIMÉES ET NUMÉRIQUES par Léon Verbeek...................................................................................................................................... 2 BIBLIOGRAPHIE .................................................................................................................................... 9 Section 1. Art plastique au Congo ............................................................................................9 Section 2. Thèses - Mémoires - Travaux de fin de cycle........................................................58 Section 3. Art plastique en Afrique.........................................................................................64 Section 4. Expositions - Catalogues - Commentaires .............................................................87 Section 5. Art et religion.......................................................................................................135 Section 6. Art réalisé par des occidentaux au Congo............................................................146 Section 7. Art de l’habillement et de la parure .....................................................................154 Section 8. Peinture murale ....................................................................................................157 Section 9. Bandes dessinées - publications illustrées – caricatures ......................................159 L’ART PLASTIQUE DANS LES JOURNAUX ET HEBDOMADAIRES DE LUBUMBASHI par Songa -

(2015): a Sangoma's Story of South Africa

Duiwelsdorp (2015): A Sangoma’s Story of South Africa [Carla / Espost/ ESPCAR002] A minor dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Screenwriting [Master of Arts in Screenwriting] Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town [2015] COMPULSORY DECLARATIONUniversity of Cape Town This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature: Date: The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Abstract “I live my life with stories that came before me. I tell stories because of stories that were told before. I wrote a story, a screenplay, called Duiwelsdorp ‘Devil Town’ because of stories that were told before me, to me and now a story lives within me. I am a storyteller because I am a woman, born from woman, alive through story. I am a woman because I give birth - to story, who actually first gave birth to me…It is in this sense that I then take up my place next to this “new generation of post-apartheid South African filmmakers” (storytellers/historians) and assume the duty of reminding my society “of its near and distant origins, of the experiences that shaped it, of its cultural wellsprings” (Confino, 1997: 1187).