Zambia Briefing Packet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cbr Africa Conference Host Day Tour Program

CBR AFRICA CONFERENCE HOST DAY TOUR PROGRAM Friday 11th May 2018 Start Time: 09:00 Hours TOUR 1 CHAMINUKA LUXURY LODGE AND GAME RESERVE Friday May 11, 2018 09h 00 Departure from Hotel Intercontinental 10h 00 Arrive at Chaminuka met by the General Manager Briefing on Chaminuka and program for the day 10h 15 Activities (At Delegates choice) • Game Drives / Walking Safaris • Walk with Cheetah • Cheese Production Plant and Cheese and wine tasting • Boat cruise • Fishing 13h 00 Lunch 14h 30 Departure for the city 15h 30 End of Host Day program Afternoon at leisure – Markets and Shopping Malls ABOUT CHAMINUKA Chaminuka is a synopsis of Africa. From the concept, to the design, to the execution to its collections of African Art and Wildlife, to its way of life, it is the creation of Andrew and Danae Sardanis, who made Chaminuka their home since 1978. Chaminuka is a village on a hill overlooking Lake Chitoka; it is some 10,000 acres of pristine Miombo woodland and savannah; it is the roar of the lion and the laughter of the hyena; it is the elephant and the 1 giraffe and the zebra and the eland and the sable and all the other animals of the Zambian bush; and it is the fish eagle and the kingfisher and the ibis and the egrets and the storks and the ducks and the geese and the other migratory birds that visit its lakes for rest and recuperation during their long annual sojourns from the Antarctic to the Russian steppes and back. And it is the huge private collection of contemporary African paintings and sculpture as well as traditional artefacts - more than one thousand pieces - acquired from all over Africa over a period of 50 years. -

Chiefs, Policing, and Vigilantes: “Cleaning Up” the Caprivi Borderland of Namibia

BUUR_Ch03.qxd 31/5/07 8:48 PM Page 79 CHAPTER 3 Chiefs, Policing, and Vigilantes: “Cleaning Up” the Caprivi Borderland of Namibia Wolfgang Zeller Introduction Scholars examining practices of territorial control and administrative action in sub-Saharan Africa have in recent years drawn attention to the analytical problems of locating their proponents unambiguously within or outside the realm of the state (Lund 2001; Englebert 2002; Nugent 2002; Chabal and Daloz 1999; Bayart et al. 1999). This chapter analyzes situations in which state practices intersect with non- state practices in the sense of the state- (and donor-)sponsored out- sourcing of policing functions to chiefs and vigilantes, where chiefs act as lower-tier representatives of state authority. My point of departure is an administrative reform introduced by the Namibian Minister of Home Affairs, Jerry Ekandjo, in August 2002, which took place in the town Bukalo in Namibia’s northeastern Caprivi Region. Bukalo is the residence of the chief of the Subiya people and his khuta (Silozi, council of chiefs and advisors).1 Before an audience of several hundred Subiya and their indunas (Silozi, chief or headman), the minister announced two aspects of the reform that had consequences for policing the border with Zambia. First, Namibian men from the border area were to be trained and deployed to patrol the border as “police reservists,” locally referred to as “vigilantes,” Secondly, Namibian police were going to conduct a “clean-up” of the entire Caprivi Region, during which all citizens of BUUR_Ch03.qxd 31/5/07 8:48 PM Page 80 80 WOLFGANG ZELLER Zambia living and working permanently or part-time in Caprivi without legal documents would be rounded up, arrested, and deported back to Zambia. -

Liste Des Indicatifs Téléphoniques Internationaux Par Indicatif 1 Liste Des Indicatifs Téléphoniques Internationaux Par Indicatif

Liste des indicatifs téléphoniques internationaux par indicatif 1 Liste des indicatifs téléphoniques internationaux par indicatif Voici la liste des indicatifs téléphoniques internationaux, permettant d'utiliser les services téléphoniques dans un autre pays. La liste correspond à celle établie par l'Union internationale des télécommunications, dans sa recommandation UIT-T E.164. du 1er février 2004. Liste par pays | Liste par indicatifs Le symbole « + » devant les indicatifs symbolise la séquence d’accès vers l’international. Cette séquence change suivant le pays d’appel ou le terminal utilisé. Depuis la majorité des pays (dont la France), « + » doit être remplacé par « 00 » (qui est le préfixe recommandé). Par exemple, pour appeler en Hongrie (dont l’indicatif international est +36) depuis la France, il faut composer un Indicatifs internationaux par zone numéro du type « 0036######### ». En revanche, depuis les États-Unis, le Canada ou un pays de la zone 1 (Amérique du Nord et Caraïbes), « + » doit être composé comme « 011 ». D’autres séquences sont utilisées en Russie et dans les anciens pays de l’URSS, typiquement le « 90 ». Autrefois, la France utilisait à cette fin le « 19 ». Sur certains téléphones mobiles, il est possible d’entrer le symbole « + » directement en maintenant la touche « 0 » pressée plus longtemps au début du numéro à composer. Mais à partir d’un poste fixe, le « + » n'est pas accessible et il faut généralement taper à la main la séquence d’accès (code d’accès vers l'international) selon le pays d’où on appelle. Zone 0 La zone 0 est pour l'instant réservée à une utilisation future non encore établie. -

War Prevention Works 50 Stories of People Resolving Conflict by Dylan Mathews War Prevention OXFORD • RESEARCH • Groupworks 50 Stories of People Resolving Conflict

OXFORD • RESEARCH • GROUP war prevention works 50 stories of people resolving conflict by Dylan Mathews war prevention works OXFORD • RESEARCH • GROUP 50 stories of people resolving conflict Oxford Research Group is a small independent team of Oxford Research Group was Written and researched by researchers and support staff concentrating on nuclear established in 1982. It is a public Dylan Mathews company limited by guarantee with weapons decision-making and the prevention of war. Produced by charitable status, governed by a We aim to assist in the building of a more secure world Scilla Elworthy Board of Directors and supported with Robin McAfee without nuclear weapons and to promote non-violent by a Council of Advisers. The and Simone Schaupp solutions to conflict. Group enjoys a strong reputation Design and illustrations by for objective and effective Paul V Vernon Our work involves: We bring policy-makers – senior research, and attracts the support • Researching how policy government officials, the military, of foundations, charities and The front and back cover features the painting ‘Lightness in Dark’ scientists, weapons designers and private individuals, many of decisions are made and who from a series of nine paintings by makes them. strategists – together with Quaker origin, in Britain, Gabrielle Rifkind • Promoting accountability independent experts Europe and the and transparency. to develop ways In this United States. It • Providing information on current past the new millennium, has no political OXFORD • RESEARCH • GROUP decisions so that public debate obstacles to human beings are faced with affiliations. can take place. nuclear challenges of planetary survival 51 Plantation Road, • Fostering dialogue between disarmament. -

Zambia Page 1 of 8

Zambia Page 1 of 8 Zambia Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2003 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 25, 2004 Zambia is a republic governed by a president and a unicameral national assembly. Since 1991, multiparty elections have resulted in the victory of the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD). MMD candidate Levy Mwanawasa was elected President in 2001, and the MMD won 69 out of 150 elected seats in the National Assembly. Domestic and international observer groups noted general transparency during the voting; however, they criticized several irregularities. Opposition parties challenged the election results in court, and court proceedings were ongoing at year's end. The anti-corruption campaign launched in 2002 continued during the year and resulted in the removal of Vice President Kavindele and the arrest of former President Chiluba and many of his supporters. The Constitution mandates an independent judiciary, and the Government generally respected this provision; however, the judicial system was hampered by lack of resources, inefficiency, and reports of possible corruption. The police, divided into regular and paramilitary units under the Ministry of Home Affairs, have primary responsibility for maintaining law and order. The Zambia Security and Intelligence Service (ZSIS), under the Office of the President, is responsible for intelligence and internal security. Civilian authorities maintained effective control of the security forces. Members of the security forces committed numerous serious human rights abuses. Approximately 60 percent of the labor force worked in agriculture, although agriculture contributed only 15 percent to the gross domestic product. Economic growth increased to 4 percent for the year. -

Abstract Art and the Contested Ground of African Modernisms

ABSTRACT ART AND THE CONTESTED GROUND OF AFRICAN MODERNISMS By PATRICK MUMBA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER of FINE ART of RHODES UNIVERSITY November 2015 Supervisor: Tanya Poole Co-Supervisor: Prof. Ruth Simbao ABSTRACT This submission for a Masters of Fine Art consists of a thesis titled Abstract Art and the Contested Ground of African Modernisms developed as a document to support the exhibition Time in Between. The exhibition addresses the fact that nothing is permanent in life, and uses abstract paintings that reveal in-between time through an engagement with the processes of ageing and decaying. Life is always a temporary situation, an idea which I develop as Time in Between, the beginning and the ending, the young and the aged, the new and the old. In my painting practice I break down these dichotomies, questioning how abstractions engage with the relative notion of time and how this links to the processes of ageing and decaying in life. I relate this ageing process to the aesthetic process of moving from representational art to semi-abstract art, and to complete abstraction, when the object or material reaches a wholly unrecognisable stage. My practice is concerned not only with the aesthetics of these paintings but also, more importantly, with translating each specific theme into the formal qualities of abstraction. In my thesis I analyse abstraction in relation to ‘African Modernisms’ and critique the notion that African abstraction is not ‘African’ but a mere copy of Western Modernism. In response to this notion, I have used a study of abstraction to interrogate notions of so-called ‘African-ness’ or ‘Zambian-ness’, whilst simultaneously challenging the Western stereotypical view of African modern art. -

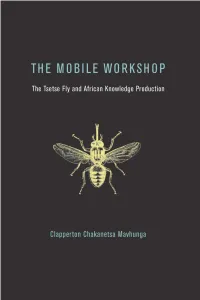

The Mobile Workshop

The Mobile Workshop The Mobile Workshop The Tsetse Fly and African Knowledge Production Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2018 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in ITC Stone Sans Std and ITC Stone Serif Std by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. ISBN: 978-0-262-53502-1 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For Mildred Maidei Contents Preface: Before We Begin … ix Introducing Mhesvi and Ruzivo Rwemhesvi 1 1 How Vanhu Managed Tsetse 29 2 Translation into Science and Policy 49 3 Knowing a Fly 67 4 How to Trap a Fly 91 5 Attacking the Fly from Within: Parasitization and Sterilization 117 6 Exposing the Fly to Its Enemies 131 7 Cordon Sanitaire: Prophylactic Settlement 153 8 Traffic Control: A Surveillance System for Unwanted Passengers 171 9 Starving the Fly 187 10 The Coming of the Organochlorine Pesticide 211 11 Bombing Flies 223 12 The Work of Ground Spraying: Incoming Machines in Vatema’s Hands 247 13 DDT, Pollution, and Gomarara: A Muted Debate 267 14 Chemoprophylactics 289 15 Unleashed: Mhesvi in a Time of War 305 Conclusion: Vatema as Intellectual Agents 317 Glossary 321 Notes 337 References 363 Index 407 Preface: Before We Begin … Preface Preface © Massachusetts Institute of TechnologyAll Rights Reserved The Mobile Workshop: The Tsetse Fly and African Knowledge Production is a project about African understandings of their surroundings. -

Migration in Zambia Migration in Zambia

Migration in Zambia A COUNTRY PROFILE 2019 Migration in Zambia in Migration A COUNTRY PROFILE 2019 PROFILE A COUNTRY Kenya Democratic Republic of the Congo United Republic of Tanzania Angola Malawi Zambia Mozambique Madagascar Zimbabwe Namibia Botswana South Africa International Organization for Migration P.O. Box 32036 Rhodes Park Plot No. 4626 Mwaimwena Road, Lusaka, Zambia Tel.: +260 211 254 055 • Fax: +260 211 253 856 Email: [email protected] • Website: www.iom.int The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in the meeting of operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher: International Organization for Migration P.O. Box 32036 Rhodes Park Plot No. 4626 Mwaimwena Road, Lusaka, Zambia Tel.: +260 211 254 055 Fax: +260 211 253 856 Email: [email protected] Website: www.iom.int Cover: This map is for illustration purposes only. The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the International Organization for Migration or the Government of Zambia. -

The Living Heritage of Traditional Names in Postcolonial Zambia

Osward Chanda PORTABLE INHERITANCE: THE LIVING HERITAGE OF TRADITIONAL NAMES IN POSTCOLONIAL ZAMBIA MA Thesis in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Central European University Budapest June 2020 CEU eTD Collection PORTABLE INHERITANCE: THE LIVING HERITAGE OF TRADITIONAL NAMES IN POSTCOLONIAL ZAMBIA by Osward Chanda (Zambia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest June 2020 PORTABLE INHERITANCE: THE LIVING HERITAGE OF TRADITIONAL NAMES IN POSTCOLONIAL ZAMBIA by Osward Chanda (Zambia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Cultural Heritage Studies: Academic Research, Policy, Management. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest June 2020 PORTABLE INHERITANCE: THE LIVING HERITAGE OF TRADITIONAL NAMES IN POSTCOLONIAL ZAMBIA by Osward Chanda (Zambia) Thesis submitted -

Ctbl-Watch Africa Issue 28 | April 2016

CTBL-WATCH AFRICA ISSUE 28 | APRIL 2016 CMA CGM OFFERS NEW LAND CORRIDORS ACROSS MAURITANIA OPENS GATEWAY TO LANDLOCKED COUNTRIES IN NORTH WEST AFRICA Full Story On Page 5 Pan Africa: Region Investing Kenya/Uganda/Rwanda: Joint Kenya: Northern Corridor SGR US$30B On 11,000KM Of Rail 07Electronic Cargo Tracking 09Construction Project 17 CTBL-WATCH AFRICA ISSUE 28 | APRIL 2016 Contents 03 | Corridor Review 05 | African Group News New: CMA CGM Offers New Land Corridors Across Mauritania, Opens Gateway To Landlocked Countries In North West Africa 07 | Pan Africa Region Investing US$30 Billion On 11,000 KM Of Rail 09 | Eastern & Southern Africa Ethiopia: US$222 Million Road To Be Constructed Kenya/Tanzania: AfDB Approves US$228 Million For Strategic Road Kenya/Uganda/Rwanda: Joint Electronic Cargo Tracking Starts June Kenya: New Mombasa Bridge Construction Design / Northern Corridor SGR Construction Project Taking Shape / Funding Talks On Naivasha-Nairobi Rail Link / Kenya Seeks Operator For New Railway / Chinese Firm To Build Communication Solution / Chinese Firm Sign Pact for Naivasha-Malaba SGR Project Malawi/Zambia: Malawi-Zambia Eye Tazara Line Mozambique: EU To Pay €16 Million For Road Repairs / New Bridge To Increase Maputo-Swaziland Rail Traffic Namibia: Roads Authority Earmark Budget For Construction / Phase 1 Port Rail Upgrade Completed Rwanda/Tanzania: Rusumo Border Facilities Launched Tanzanian President John Pombe Magufuli and Rwandan President Rwanda: Base-Gicumbi-Rukomo-Nyagatare Road Project / Rubavu Warehouse To Ease Cross-Border -

Encounters Between Jesuit and Protestant Missionaries in Their Approaches to Evangelization in Zambia

chapter 4 Encounters between Jesuit and Protestant Missionaries in their Approaches to Evangelization in Zambia Choobe Maambo, s.j. Africa’s reception of Christianity and the pace at which the faith permeated the continent were incredibly slow. Although the north, especially Ethiopia and Egypt, is believed to have come under Christian influence as early as the first century, it was not until the fourth century that Christianity became more widespread in north Africa under the influence of the patristic fathers. From the time of the African church fathers up until the fifteenth century, there was no trace of the Christian church south of the Sahara. According to William Lane, s.j.: It was not until the end of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that Christianity began to spread to the more southerly areas of Africa. The Portuguese, in their search for a sea route to India, set up bases along the East and West African coasts. Since Portugal was a Christian country, mis- sionaries followed in the wake of the traders with the aim of spreading the Gospel and setting up the Church along the African coasts.1 Prince Henry the Navigator (1394–1460) of Portugal was the man behind these expeditions, in which priests “served as chaplains to the new trading settle- ments and as missionaries to neighboring African people.”2 Hence, at the close of the sixteenth century, Christian missionary work had increased significantly south of the Sahara. In Central Africa, and more specifically in the Kingdom of Kongo, the Gospel was preached to the king and his royal family as early as 1484. -

For Use by the Author Only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV Afrika-Studiecentrum Series

David Livingstone and the Myth of African Poverty and Disease For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV Afrika-Studiecentrum Series Series Editors Lungisile Ntsebeza (University of Cape Town, South Africa) Harry Wels (VU University Amsterdam, The Netherlands, African Studies Centre, Leiden, The Netherlands and University of the Western Cape, South Africa) Editorial Board Emmanuel Akyeampong (Harvard University, USA) Akosua Adomako Ampofo (University of Ghana, Legon) Fatima Harrak (University of Mohammed V, Morocco) Francis Nyamnjoh (University of Cape Town, South Africa) Robert Ross (Leiden University, The Netherlands) VOLUME 35 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/asc For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV David Livingstone and the Myth of African Poverty and Disease A Close Examination of His Writing on the Pre-colonial Era By Sjoerd Rijpma LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2015 Koninklijke Brill NV © Translation: Mrs R. van Stolk. The original text of this story was written by Sjoerd Rijpma (pronounced: Rypma) in Dutch—according to David Livingstone ‘of all languages the nastiest. It is good only for oxen’ (Livingstone, Family Letters 1841–1856, vol. 1, ed. I. Schapera (London: Chatto and Windus, 1959), 190). This is not the reason it has been translated into English. Cover illustration: A young African herd boy sitting on a large ox. The photograph belongs to a series of Church of Scotland Foreign Missions Committee lantern slides relating to David Livingstone. Photographer unknown. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rijpma, Sjoerd, 1931–2015, author. David Livingstone and the myth of African poverty and disease : a close examination of his writing on the pre-colonial era / by Sjoerd Rijpma.