ECOLOGIES WITHOUT BORDERS? Remapping & Remaking Conservation in the Okavango-Zambezi Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hunters Paths

CONSERVATION Happy Birthday Selous! Africa’s Oldest Protected Area Celebrates The Selous Game Reserve, in southern Tanzania, is not only Africa’s largest protected area, but also its oldest. It celebrated its 120th birthday on May 7th. Although a portion of the reserve is used for photo-tourism, the majority of it is primarily for sustainable hunting tourism, making it Africa’s largest hunting area. Text and Photos: Dr. Rolf D. Baldus | Maps by Mike Shand hen Germany, a latecomer made clear by von Wissmann, then Imperial to European colonial expan- Governor, in a decree: “I felt obliged to issue W sion, declared Tanganyika this ordinance in order to conserve wildlife a Protectorate in 1885, the slaughter of and to prevent many species from becoming elephants had already surpassed its peak, extinct, which would happen soon if present and they were becoming rare. Two hun- conditions prevail ... We are obliged to think dred tons of ivory were exported every also of future generations, and should secure year from Zanzibar, the equivalent of 12,000 them the opportunity to enjoy the pleasure elephants. Commercial hunters could buy of hunting African game in the future.” licenses to shoot elephants for their ivory. It was commercial culling and not tradi- In Germany, fears of the imminent extinc- tional hunting by the local African population, tion of the formerly rich wildlife in Ger- which was considered unsustainable by the man East Africa became widespread after government. In their opinion, even a game- hunter-conservationists, among them Carl rich country like German East Africa could Georg Schillings, alerted the public in best- not conserve its wildlife in the long term if selling books. -

Results of Railway Privatization in Africa

36005 THE WORLD BANK GROUP WASHINGTON, D.C. TP-8 TRANSPORT PAPERS SEPTEMBER 2005 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Results of Railway Privatization in Africa Richard Bullock. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized TRANSPORT SECTOR BOARD RESULTS OF RAILWAY PRIVATIZATION IN AFRICA Richard Bullock TRANSPORT THE WORLD BANK SECTOR Washington, D.C. BOARD © 2005 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone 202-473-1000 Internet www/worldbank.org Published September 2005 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. This paper has been produced with the financial assistance of a grant from TRISP, a partnership between the UK Department for International Development and the World Bank, for learning and sharing of knowledge in the fields of transport and rural infrastructure services. To order additional copies of this publication, please send an e-mail to the Transport Help Desk [email protected] Transport publications are available on-line at http://www.worldbank.org/transport/ RESULTS OF RAILWAY PRIVATIZATION IN AFRICA iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface .................................................................................................................................v Author’s Note ...................................................................................................................... -

To What Extent Was World War Two the Catalyst Or Cause of British Decolonisation?

To what extent was World War Two the catalyst or cause of British Decolonisation? Centre Number: FR042 Word Count: 3992 Words Did Britain and her colonies truly stand united for “Faith, King and Empire” in 1920, and to what extent was Second World War responsible for the collapse of this vast empire? Cover Picture: K.C. Byrde (1920). Empire of the Sun [online]. Available at: http://worldwararmageddon.blogspot.com/2010/09/empire-of-sun.html Last accessed: 27th January 2012 Table of Contents Abstract Page 2 Introduction Page 3 Investigation Page 4 – Page 12 • The War Caused Decolonisation in Page 4 – Page 7 African Colonies • The War acted as a Catalyst in an Page 7 – Page 8 international shift against Imperialism • The War Slowed down Decolonisation in Page 8 – Page 10 Malaya • The War Acted as a Catalyst with regard Page 10 – Page 11 to India • The Method of British Imperialism was Page 11 – Page 12 condemned to fail from the start. Conclusion Page 13 Bibliography Page 14 – Page 15 1 Abstract This question answered in this extended essay is “Was World War Two the catalyst or the cause of British Decolonisation.” This is achieved by analysing how the war ultimately affected the British Empire. The British presence in Africa is examined, and the motives behind African decolonisation can be attributed directly to the War. In areas such as India, once called the ‘Jewel of the British Empire,’ it’s movement towards independence had occurred decades before the outbreak of the War, which there acted merely as a Catalyst in this instance. -

Charisma and Politics in Post-Colonial Africa

CENTRE FOR SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH Charisma and politics in post-colonial Africa Sishuwa Sishuwa CSSR Working Paper No. 446 January 2020 Published by the Centre for Social Science Research University of Cape Town 2020 http://www.cssr.uct.ac.za This Working Paper can be downloaded from: http://cssr.uct.ac.za/pub/wp/446 ISBN: 978-1-77011-433-3 © Centre for Social Science Research, UCT, 2020 About the author: Sishuwa Sishuwa is a post-doctoral research fellow in the Institute for Democracy, Citizenship and Public Policy in Africa, at UCT. His PhD (from Oxford University) was a political biography of Zambian politician and president Michael Sata. Charisma and politics in post-colonial Africa Abstract This paper examines the interaction between charisma and politics in Africa. Two broad groups of charismatic political leaders are discussed: those who came to the fore during the era of independence struggles and saw themselves as an embodiment of their nation states and having a transformative impact over the societies they led, and those who emerged largely in response to the failure of the first group or the discontent of post-colonial delivery, and sought political power to enhance their own personal interests. In both instances, the leaders emerged in a context of a crisis: the collapse of colonialism, the disintegration of the one-party state model and economic collapse. Keywords: charisma; leadership; colonialism; one-party state; democracy. 1. Introduction The concept of charisma entered the lexicon of the social sciences more than a century ago and is credited to German sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920). -

Tanzania-Zambia Railway: Escape Route from Neocolonial Control? Alvin W

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Anthropology Faculty Publications Anthropology 1970 Tanzania-Zambia Railway: Escape Route from Neocolonial Control? Alvin W. Wolfe [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/ant_facpub Part of the Anthropology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Wolfe, Alvin W., "Tanzania-Zambia Railway: Escape Route from Neocolonial Control?" (1970). Anthropology Faculty Publications. 10. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/ant_facpub/10 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. f.~m NONALIGNED THIRD WORLD ANNUAL 1970 ';;~~: Books International ot DH-T~ %n~ernational St. Louis, Missouri, USA . \ ESCAPE ROUTE ALVINW. WOLFE* THE FIRST REQUISITE for African development is that African countries combine what little wealth and power they have toward the end of getting a greater share of the products of world industry. They may be able to get that greater share by forcing through better terms of trade or better terms in aid, but they will never get any greater share by continuing along present paths, whereby each weak and poor country "negotiates" separately with strong and rich developed countries and supranational emities such as the World Bank and major private companies. If they hope to break thos.e ne,ocolonial bonds, Africans must unite- -

Zambezi River Safari and Houseboat Cruise 11-Day Zimbabwe Tour with 5-Day Lake Kariba Cruise

Zambezi River Safari and Houseboat Cruise 11-Day Zimbabwe Tour with 5-Day Lake Kariba Cruise Zambezi River Safari and Houseboat Cruise Discover one of Africa’s hidden treasures on an unforgettable journey amid Zimbabwe’s natural beauty. Explore magnificent waterfalls, pristine national parks, and enjoy thrilling wildlife safaris. Discover one of Africa’s hidden treasures on an unforgettable journey amid Zimbabwe’s natural beauty. Explore magnificent waterfalls, pristine national parks, and enjoy thrilling wildlife safaris. The Victoria Falls are one of the world’s most stunning natural wonders. Lake Kariba is the largest human-made lake in the world by volume. These are just two of the highlights of your exclusive houseboat adventure in Zimbabwe! What Makes Your Journey Unique • Experience the mighty Zambezi River • Enjoy a unique and exclusive cruise on Lake Kariba • Discover Zimbabwe on a houseboat featuring nine cabins, all with panoramic views • Visit the immense Victoria Falls, also known as the Smoke that Thunders • Explore the Mana Pools National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site • Go on a safari in the Matusadona National Park, home to all big five game animals Dates Info and Booking Susanne Willeke E-Mail: [email protected] Itinerary Day 1., Zimbabwe Welcomes You Your first day in Zimbabwe immediately gets off to the right start—with a smile from your driver. Once you arrive at your lodge, you begin to explore its amenities and surrounding areas. After lunch, you take advantage of your private balcony and gaze at the unfettered panorama of the gorgeous Zambezi National Park. A nearby watering hole attracts local wildlife, making for some beautiful and spontaneous photography sessions. -

The Black Power Movement

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 1: Amiri Baraka from Black Arts to Black Radicalism Editorial Adviser Komozi Woodard Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 1, Amiri Baraka from Black arts to Black radicalism [microform] / editorial adviser, Komozi Woodard; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. p. cm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide, compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. ISBN 1-55655-834-1 1. Afro-Americans—Civil rights—History—20th century—Sources. 2. Black power—United States—History—Sources. 3. Black nationalism—United States— History—20th century—Sources. 4. Baraka, Imamu Amiri, 1934– —Archives. I. Woodard, Komozi. II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Lewis, Daniel, 1972– . Guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. IV. Title: Amiri Baraka from black arts to Black radicalism. V. Series. E185.615 323.1'196073'09045—dc21 00-068556 CIP Copyright © 2001 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-834-1. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................ -

Life of Frederick Courtenay Selous, D.S.O. Capt

LIFE OF FREDERICK COURTENAY SELOUS, D.S.O. CAPT. 25TH ROYAL FUSILIERS Chapter XI - XV BY J. G. MILLAIS, F.Z.S. CHAPTER XI 1906-1907 In April, 1906, Selous went all the way to Bosnia just to take the nest and eggs of the Nutcracker, and those who are not naturalists can scarcely understand such excessive enthusiasm. This little piece of wandering, however, seemed only an incentive to further restlessness, which he himself admits, and he was off again on July 12th to Western America for another hunt in the forests, this time on the South Fork of the MacMillan river. On August 5th he started from Whitehorse on the Yukon on his long canoe-journey down the river, for he wished to save the expense of taking the steamer to the mouth of the Pelly. He was accompanied by Charles Coghlan, who had been with him the previous year, and Roderick Thomas, a hard-bitten old traveller of the North- West. Selous found no difficulty in shooting the rapids on the Yukon, and had a pleasant trip in fine weather to Fort Selkirk, where he entered the Pelly on August 9th. Here he was lucky enough to kill a cow moose, and thus had an abundance of meat to take him on the long up-stream journey to the MacMillan mountains, which could only be effected by poling and towing. On August 18th he killed a lynx. At last, on August 28th, he reached a point on the South Fork of the MacMillan, where it became necessary to leave the canoe and pack provisions and outfit up to timber-line. -

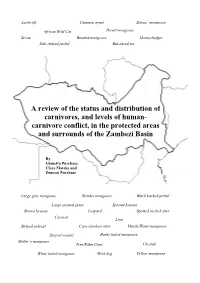

A Review of the Status and Distribution of Carnivores, and Levels of Human- Carnivore Conflict, in the Protected Areas and Surrounds of the Zambezi Basin

Aardwolf Common genet Selous’ mongoose African Wild Cat Dwarf mongoose Serval Banded mongoose Honey badger Side striped jackal Bat-eared fox A review of the status and distribution of carnivores, and levels of human- carnivore conflict, in the protected areas and surrounds of the Zambezi Basin By Gianetta Purchase, Clare Mateke and Duncan Purchase Large grey mongoose Slender mongoose Black backed jackal Large spotted genet Spotted hyaena Brown hyaena Leopard Spotted necked otter Caracal Lion Striped polecat Cape clawless otter Marsh/Water mongoose Striped weasel Bushy tailed mongoose Meller’s mongoose Tree/Palm Civet Cheetah White tailed mongoose Wild dog Yellow mongoose A review of the status and distribution of carnivores, and levels of human- carnivore conflict, in the protected areas and surrounds of the Zambezi Basin By Gianetta Purchase, Clare Mateke and Duncan Purchase © The Zambezi Society 2007 Suggested citation Purchase, G.K., Mateke, C. & Purchase, D. 2007. A review of the status and distribution of carnivores, and levels of human carnivore conflict, in the protected areas and surrounds of the Zambezi Basin. Unpublished report. The Zambezi Society, Bulawayo. 79pp Mission Statement To promote the conservation and environmentally sound management of the Zambezi Basin for the benefit of its biological and human communities THE ZAMBEZI SOCIETY was established in 1982. Its goals include the conservation of biological diversity and wilderness in the Zambezi Basin through the application of sustainable, scientifically sound natural resource management strategies. Through its skills and experience in advocacy and information dissemination, it interprets biodiversity information collected by specialists, and uses it to implement technically sound conservation projects within the Zambezi Basin. -

British Community Development in Central Africa, 1945-55

School of History University of New South Wales Equivocal Empire: British Community Development in Central Africa, 1945-55 Daniel Kark A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of New South Wales, Australia 2008 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed …………………………………………….............. Date …………………………………………….............. For my parents, Vanessa and Adrian. For what you forfeited. Abstract This thesis resituates the Community Development programme as the key social intervention attempted by the British Colonial Office in Africa in the late 1940s and early 1950s. A preference for planning, growing confidence in metropolitan intervention, and the gradualist determination of Fabian socialist politicians and experts resulted in a programme that stressed modernity, progressive individualism, initiative, cooperative communities and a new type of responsible citizenship. Eventual self-rule would be well-served by this new contract between colonial administrations and African citizens. -

Zimbabwe Deluxe

Zimbabwe Deluxe Your professional partner for perfectly organised travel arrangements to Southern and Eastern Africa since more than 15 years Zimbabwe Deluxe Selected properties Combination of privately guided tour and Fly-in safari with guide from the respective camps Victoria Falls - Hwange National Park – Matusadona National Park Day 01: Victoria Falls On arrival in Victoria Falls you are being met by a representative of Victoria Falls River Lodge for your road transfer to the lodge, which takes about 20 minutes. On arrival we have planned in for a late lunch for you at the camp. In the later afternoon, you may like to enjoy a sunset cruise on the majestic Zambezi River, which is included in your arrangement with the lodge. Victoria Falls River Lodge L,D Day 02: Victoria Falls Enjoy one full day in this beautiful setting. We have organised for a privately guided tour of the Falls for you, which takes about two hours. One of the seven natural wonders of the world the Victoria Falls is a truly spectacular sight. On your privately guided tour of the Zimbabwe side of the Falls you have the opportunity, to experience its awesome unspoilt grandeur as your guide explains how this 150-million-year-old phenomenon was created. Start at Livingstone's statue and Devil's Cataract and proceed through the rain forest to Danger Point. The walk is approx. 3 km and there are many view points along the way. For the afternoon, you may like to relax or partaking in optional activities offered by the camp. It is also possible to participate in the afternoon game drive of the lodge in the Zambezi National Park, which is also included in your arrangement. -

The Colossus of Rhodes: a Powerful Enigma

XXXXXX The Colossus of Rhodes: A Powerful Enigma BY LONE WRIEDT SØRENSEN 15 DOCUMENTING ANCIENT RHODES: ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITIONS AND RHODIAN ANTIQUITIES The Colossus of Rhodes: of the technical details concerning the construction of the Colossus. According to him the feet of the statue, A Powerful Enigma which were filled in rocks, were fixed upon a base of white marble.5 Furthermore, Johannes Malalas, a historian from Antiochia at Odessa (AD 490-575), reports in his book (ch. BY LONE WRIEDT SØRENSEN 11.18) that 312 years after its fall, during which time none of it went missing, Hadrian re-erected it on the same spot at a cost of three Centenaria of gold, the fact of which was The Colossus of Rhodes, the icon of the island, occupies inscribed on its base. a unique position from Antiquity to present times. No- The size of the statue and the fact that it was made one can claim to have found or excavated the Colossus, of bronze have particularly intrigued those who have let alone describe with certainty what it looked like, how commented on it. Using Philo’s account in De Septem Orbis it was constructed or where it was erected. Over the years Spectaculis, the sculptor Herbert Maryon proposed that for it has nonetheless been the subject of many studies based the amount of 500 talents the statue mentioned by Philo on archaeological and textual data, and it still attracts must have been constructed on the site from thin, beaten- scholarly interest – and, indeed, other kinds of interest.1 out sheets, while Haynes with reference to the same text The biography of the statue as a concept is remarkable.