The Multistoried House. Twentieth-Century Encounters With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

George Washington Papers, Series 2, Letterbooks 1754-1799

George Washington Papers, Series 2, Letterbooks 1754-1799 To LUND WASHINGTON February 28, 1778. …If you should happen to draw a prize in the militia , I must provide a man, either there or here, in your room; as nothing but your having the charge of my business, and the entire confidence I repose in you, could make me tolerable easy from home for such a length of time as I have been, and am likely to be. This therefore leads me to say, that I hope no motive, however powerful, will induce you to leave my business, whilst I, in a manner, am banished from home; because I should be unhappy to see it in common hands. For this reason, altho' from accidents and misfortunes not to be averted by human foresight, I make little or nothing from my Estate, I am still willing to increase your wages, and make it worth your while to continue with me. To go on in the improvement of my Estate in the manner heretofore described to you, fulfilling my plans, and keeping my property together, are the principal objects I have in view during these troubles; and firmly believing that they will be accomplished under your management, as far as circumstances and acts of providence will allow, I feel quite easy under disappointments; which I should not do, if my business was in common hands, 38 liable to suspicions. I am, etc. 38. Extract in “Washington's Letter Book, No. 5.” Lund answered (March 18): “By your letter I should suppose you were apprehensive I intended to leave you. -

Nomination Form

I[]ExceIl_3. Fair 0.leriom.d Ruin. U-~wd CONDITION I (Check Onel I (Check One) I Altered Un0lt.r.d I n Mowed hipinol Sin OR!CINAL (IILnoanJ PHIIfCAL APPEARLNCE Powhatan is a classic two-story Virginia mansion of the Early Georgian period. The>rectangular structure is five bays long by two bays deep, with centered doors on front and rear. Its brickwork exhibits the highest standards of Colonial craftsmanship. The walls are laid in Flemish bond with glazed headers above the bevelled water table with English bond below. Rubbed work appears at the corners, window and door jambs, and belt course, while gauged work appears in the splayed flat arches over the windows and doors. The basement windows are topped by gauged segmental arches. The two massive interior end T-shaped chimneys are finely execute4 but are relatively late examples of their form. The chimney caps are both corbelled and gauged. ~eciusethe hbuse was gutted bi fire, none but the masonry members are I I original. Nearly all the evidences of.the post-fire rebuilding were m removed during a thorough renwation in 1948. As part of the renovation, rn the hipped roof was replaced following the lines of the original roof as indicated by scars in the chimneys. The roof is pierced by dormer rn windows which may or my not have bean an original feature, The Early - Georgian style sash, sills, architraves, and modillion cornice also date z from the renovation. While nearly all the interior woodwork dates from m 1948, the double pile plan with central hall survives. -

Nomination Form

141 Form No. 10-300 ,o- ' 'J-R - ft>( 15/r (i;, ~~- V ' I UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FOR NPSUSE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF IIlSTORIC PLACES RECEIVED INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS- - - - - [EINAME HISTORIC Shack Mountain AND/OR COMMON raLOCATION 2 miles NNW of Charlottesville; .3 mile E of Ivy Creek; .4 mile N of STREET & NUMBER State Route 657; 1 mile NNW of intersection of State Routes 657 and 743. _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Charlottesville _2( VICINITY OF Seventh (J. Kenneth Robinson) STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Virginia 51 Albemarle 003 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT _PUBLIC XoccuP1Eo _AGRICULTURE _MUSEUM X...BUILDING!S) X..PRIVATE _UNOCCUPIED _COMMERCIAL _PARK _STRUCTURE _BOTH _WORK IN PROGRESS _EDUCATIONAL 2LPRIVATE RESIDENCE -SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE -ENTERTAINMENT -RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS -YES: RESTRICTED _GOVERNMENT _SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED - YES: UNRESTRICTED _INDUSTRIAL -TRANSPORTATION -~O _MILITARY _OTHER: [~OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mr. and Mrs. W. Bedford Moore, I II STREET & NUMBER Shack Mounta_in, Route 5 CITY. TOWN STATE Charlottesville _ VICINITY OF Virginia 22901 [ELOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Albemarle County Courthouse - ---•---------------------------------------~ STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Charlottesville. Virginia l~ REPRESENTATION I1'fEXISTING SURVEYS TITLE -

“A People Who Have Not the Pride to Record Their History Will Not Long

STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE i “A people who have not the pride to record their History will not long have virtues to make History worth recording; and Introduction no people who At the rear of Old Main at Bethany College, the sun shines through are indifferent an arcade. This passageway is filled with students today, just as it was more than a hundred years ago, as shown in a c.1885 photograph. to their past During my several visits to this college, I have lingered here enjoying the light and the student activity. It reminds me that we are part of the past need hope to as well as today. People can connect to historic resources through their make their character and setting as well as the stories they tell and the memories they make. future great.” The National Register of Historic Places recognizes historic re- sources such as Old Main. In 2000, the State Historic Preservation Office Virgil A. Lewis, first published Historic West Virginia which provided brief descriptions noted historian of our state’s National Register listings. This second edition adds approx- Mason County, imately 265 new listings, including the Huntington home of Civil Rights West Virginia activist Memphis Tennessee Garrison, the New River Gorge Bridge, Camp Caesar in Webster County, Fort Mill Ridge in Hampshire County, the Ananias Pitsenbarger Farm in Pendleton County and the Nuttallburg Coal Mining Complex in Fayette County. Each reveals the richness of our past and celebrates the stories and accomplishments of our citizens. I hope you enjoy and learn from Historic West Virginia. -

3. State/Federal Agency Certification

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1 . Name of Property historic name: ST. GEORGE'S CHAPEL other names/site number: Norborne Parish Church, 46- JF 161 2. Location street & number: Off West Virginia State Route 51 not for publication: N/A city or town vicinity: Charles Town vicinity: X state: West Virginia code: WV county: Jefferson code: 037 zip code: 25414 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this _X __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __X__ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally-^ statewide _X_ locally. ( __ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) 'Sjgnature of certifying official Date State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. (__ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau Date NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service St. George's Chapel Jefferson County, West Virginia Name of Property County, State 4. National Park Service Certification I, hereby certify that this property is: entered in the National Register See continuation sheet. -

NOMINATION FORM for NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER Dal"E

_, i.. t, 'I . •I · Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF fHE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NA Tl ON Al PARK SERVICE Virginia COUNTY, NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES James City INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DAl"E COMMON: George Wythe House ANOI OR HISTORIC, Wythe House ,__ -·-· -·-:-",-,_:,v.•.,'.•.'c:'. •i•:?-,•· \/:c+i,)"!;)'.(' :{/(;".;.\p; LC '<it\:\ STREET ANo NUMBER: On the west side of the Palace Green between the Duke of Gloucester Street and Prince George Street. --CITY -OR-------------------------------------------------1 TOWN: Williamsburg STATE COOE COUNTY · CODE Virginia •--·-:•, .,. .. __ . 1):\;¢tAs~iFiC:.Xi'tqif :_/</ >:Y /- :· T'•• .. _.L: <> , <f %%\Xfr ;?\ '" _.,..,. ., ....., .___ _ : -:-: : .•:-. ··:::-:;:.':• .;;(:;}'.)\:;:.~:y CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC z D District rn Bui /ding D Public I Public Acquisitil>n: n Occupiod Yes; 0 Restricted D Sile 0 Structu,e rn PriYate 0 In Process 0 Unoccupied D Both 0 Beir,g Con~id&red Unrestricted 0 Object 0 0 Pr&s&rvation work \ ixJ 1- in progr&ss \ D No u PRESENT USE (CJ>eck on~ or More BS Appropr/eto) D Agricultura l D Government 0 Pork 0 Trol'\sportatl on 0 Comm&nts 0 Commercial 0 Industrial 0 Pr/vote Residenco 0 Other ($pt,c/!y) D Educational D M;J itary 0 R&ligiou• D Entorta i rimenf ~ Museum 0 Scientific OWNEA' s NAME: -I"' ), Colonial Williamsburg, Inc., Division of Interpretation -I "1 w Sl"AEET AND NUMBER: UJ Goodwin Building CITY OR TOWN : STATE< CODE Willi4msburg 23185 Virginia ~~~l~'OF'.t{fi~Wtl'.]~~p'rtl&:i'.:L9~/ --._. -

Fiske Kimball and Preservation at the Powel House

Front Parlor Much like Kimball, the methods that he employed at the Powel House could bought the house in 1931, Kimball eventually supported her efforts by be problematic. However, it is important to remember that because of his presenting Landmarks with the original woodwork taken from this room (as it As you enter the front parlor, take a moment to examine the furniture in the training and experience, Kimball believed he was doing what was necessary was not being used by the Museum) and loaning her some of the furniture. room and the architecture above the fireplace. All of these pieces have been and right to save the legacy of the Powel House. His method involved Due to the return of the room’s moldings and trim, it is one of the only rooms preserved and maintained so that they could be seen and studied today. While purchasing the key architectural pieces of the house, such as the woodwork, in the house that is original and not a reconstruction. In this room then, it is this room is the simplest architecturally because it was the only room the and reconstructing them at the Art Museum to be displayed as period rooms important to think about how history is remembered and preserved. It is not general public had access to when conducting business with Samuel and later along with contemporary furniture and paintings. Today, such invasive enough to just save the physical pieces but preservation must also engage with Elizabeth Powel, it has been preserved for the sake of the stories it can tell. -

The Vaulx Family of England, Virginia, and Maryland

The Vaulx Family of England, Virginia, and Maryland Including a Discussion of Some Members of the Vass Family of Eastern Virginia Michael L. Marshall October 2012 Arms of Vaulx of Cumberland, England CONTENTS VAULX OF ENGLAND............................................................................................................ 4 Origin of Vaulx Line in England .................................................................................................................................... 4 James Vaulx “Medicus” of Wiltshire ............................................................................................................................10 VAULX FAMILY OF VIRGINIA AND MARYLAND ............................................................... 17 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................................17 Robert Vaulx, Merchant of London and Virginia.........................................................................................................17 Robert Vaulx of Westmoreland County, Virginia.........................................................................................................23 James and Elisheba Vaulx of York County, Virginia....................................................................................................33 Elisheba Vaulx............................................................................................................................................................42 -

October 1916

[Sg^gg^^ / tamiiHffiy1^ ^\\ r] ARCHITEOJVRAL D aiiiafigoj b r -- * i-ir+X. Vol. XLVI. No. 4 OCTOBER, 1919 Serial N o 25 Editor: MICHAEL A. MIKKELSEN Contributing Editor: HERBERT CROLY Business Manager: J. A. OAKLEY COVEK Water Color, by Jack Manley Rose PAGE THE AMERICAN COUNTRY HOUSE . .;. .-. 291 By Prof. Fiske Kimball. I. Practical Conditions: Natural, Economic, Social . ,. *.,, . 299 II. Artistic Conditions : Traditions and Ten^ dencies of Style . \ . .- 329 III. The Solutions : Disposition and Treatment of House and Surroundings . 350 J . .Vi Yearly Subscription United States $3.00 Foreign $4.00 Stn<7?e copies 33 cents. Entered May 22, 1902, as Second Class Matter, at New York, N. Y. Member Audit Bureau of Circulation. PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE ARCHITECTURAL:TURAL RECORD COMPANY VEST FORTIETH STKEET, NEW YORK F. T. MILLER, Pres. XL, Vice-Pres. J. W. FRANK, Sec'y-Treas. E. S. DODGE, Vice-Pi* ''< w : : f'lfvjf !?-; ^Tt;">7<"!{^if ^J^Y^^''*'C I''-" ^^ '^'^''^>'**-*'^j"^4!V; TIG. 1. DETAIL RESIDENCE OF H. BELLAS HESS, ESQ., HUNT1NGTON, L. I HOWELLS & STOKES, ARCHITECTS. AKCHITECTVKAL KECORD VOLVME XLVI NVMBER IV OCTOBER, 1919 <Amerioan Country <House By Fiskc KJmball the "country house" in America scribed "lots" of the city, where one may we understand no such single well- enjoy the informality of nature out-of- BYestablished form as the traditional doors. country house of England, fixed by cen- Much as has been written on the sub- turies of almost unalterable custom, with ject, we are still far from having any a life of its own which has been described such fundamental analysis of the Amer- as "the perfection of human society." ican country house of today as that Even in England today the great house which Hermann Muthesius in his classic yields in importance to the new and book "The English House" has given for smaller types which the rise of the middle England. -

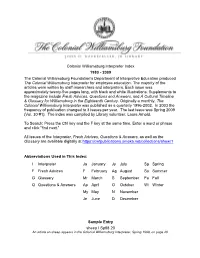

Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter Index 1980

Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter Index 1980 - 2009 The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Department of Interpretive Education produced The Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter for employee education. The majority of the articles were written by staff researchers and interpreters. Each issue was approximately twenty-five pages long, with black and white illustrations. Supplements to the magazine include Fresh Advices, Questions and Answers, and A Cultural Timeline & Glossary for Williamsburg in the Eighteenth Century. Originally a monthly, The Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter was published as a quarterly 1996-2002. In 2003 the frequency of publication changed to 3 issues per year. The last issue was Spring 2009 (Vol. 30 #1). The index was compiled by Library volunteer, Laura Arnold. To Search: Press the Ctrl key and the F key at the same time. Enter a word or phrase and click "find next.” All issues of the Interpreter, Fresh Advices, Questions & Answers, as well as the Glossary are available digitally at https://cwfpublications.omeka.net/collections/show/1 Abbreviations Used in This Index: I Interpreter Ja January Jy July Sp Spring F Fresh Advices F February Ag August Su Summer G Glossary Mr March S September Fa Fall Q Questions & Answers Ap April O October Wi Winter My May N November Je June D December Sample Entry sheep I Sp98 20 An article on sheep appears in the Colonial Williamsburg Interpreter, Spring 1998, on page 20. A abolition of slavery I Sp99 20-22, I Wi99/00 19-25, “Abuse of History: Selections from Dave Barry Slept Here, -

The Publicity of Monticello: a Private Home As Emblem and Means Benjamin Block [email protected]

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Summer Research 2013 The Publicity of Monticello: A Private Home as Emblem and Means Benjamin Block [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Architectural History and Criticism Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Block, Benjamin, "The ubP licity of Monticello: A Private Home as Emblem and Means" (2013). Summer Research. Paper 179. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research/179 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer Research by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PUBLICITY OF MONTICELLO: A PRIVATE HOME AS EMBLEM AND MEANS Ben Block Department of Art History September 24, 2013 1 THE PUBLICITY OF MONTICELLO: A PRIVATE HOME AS EMBLEM AND MEANS The next Augustan age will dawn on the other side of the Atlantic. There will, perhaps, be a Thucydides at Boston, a Xenophon at New York, and, in time, a Virgil at Mexico, and a Newton at Peru. At last, some curious traveller from Lima will visit England and give a description of the ruins of St. Paul's, like the editions of Balbec and Palmyra. - Horace Walpole 1 In the course of the study of Thomas Jefferson as architect, which began in earnest in 1916 with Fiske Kimball’s landmark study Thomas Jefferson, Architect , only recently have historians began to break out of the shell that Kimball placed around Jefferson’s architecture.