The Potential Impact of Open Data in Serbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ATP World Tour 2019

ATP World Tour 2019 Note: Grand Slams are listed in red and bold text. STARTING DATE TOURNAMENT SURFACE VENUE 31 December Hopman Cup Hard Perth, Australia Qatar Open Hard Doha, Qatar Maharashtra Open Hard Pune, India Brisbane International Hard Brisbane, Australia 7 January Auckland Open Hard Auckland, New Zealand Sydney International Hard Sydney, Australia 14 January Australian Open Hard Melbourne, Australia 28 January Davis Cup First Round Hard - 4 February Open Sud de France Hard Montpellier, France Sofia Open Hard Sofia, Bulgaria Ecuador Open Clay Quito, Ecuador 11 February Rotterdam Open Hard Rotterdam, Netherlands New York Open Hard Uniondale, United States Argentina Open Clay Buenos Aires, Argentina 18 February Rio Open Clay Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Open 13 Hard Marseille, France Delray Beach Open Hard Delray Beach, USA 25 February Dubai Tennis Championships Hard Dubai, UAE Mexican Open Hard Acapulco, Mexico Brasil Open Clay Sao Paulo, Brazil 4 March Indian Wells Masters Hard Indian Wells, United States 18 March Miami Open Hard Miami, USA 1 April Davis Cup Quarterfinals - - 8 April U.S. Men's Clay Court Championships Clay Houston, USA Grand Prix Hassan II Clay Marrakesh, Morocco 15 April Monte-Carlo Masters Clay Monte Carlo, Monaco 22 April Barcelona Open Clay Barcelona, Spain Hungarian Open Clay Budapest, Hungary 29 April Estoril Open Clay Estoril, Portugal Bavarian International Tennis Clay Munich, Germany Championships 6 May Madrid Open Clay Madrid, Spain 13 May Italian Open Clay Rome, Italy 20 May Geneva Open Clay Geneva, Switzerland -

Federer, Mike Bryan Seek Milestone Wins on Friday

MERCEDES CUP: DAY 5 MEDIA NOTES Friday, June 10, 2016 TC Weissenhof, Stuttgart, Germany | June 6-12, 2016 Draw: S-28, D-16 | Prize Money: €606,525 | Surface: Grass ATP Info Tournament Info ATP PR & Marketing www.ATPWorldTour.com www.mercedescup.de Martin Dagahs: [email protected] @ATPWorldTour @MercedesCup Press Room: +49 711 32095705 facebook.com/ATPWorldTour facebook.com/MercedesCup FEDERER, MIKE BRYAN SEEK MILESTONE WINS ON FRIDAY QUARTER-FINAL PREVIEW: No. 1 seed Roger Federer could pass Hall-of-Famer Ivan Lendl on Friday and move into second place in the Open Era with 1,072 victories. Federer faces Florian Mayer in the Mercedes Cup quarter-finals, and with a win would trail only Jimmy Connors among the winningest players since the spring of 1968. Federer has a 6-0 FedEx ATP Head 2 Head record against Mayer, including straight-set wins on German grass at the Gerry Weber Open in 2005, 2012 and 2015. Federer is not the only man with a milestone on the line in Stuttgart. Mike Bryan seeks his 1,000th doubles win when he and twin brother Bob face Oliver Marach and Fabrice Martin in a semi-final match on Court 1. Only Federer, Lendl, Connors and Daniel Nestor have earned at least 1,000 victories in singles or doubles. Bob Bryan has 985 doubles wins individually. As a team, the Bryans are 984-300. Also in action are a pair of players who won their first ATP World Tour title in Stuttgart: 2002 champion Mikhail Youzhny and 2008 champion Juan Martin del Potro. -

Thiem Makes Debut, Robredo Returns to Action Moselle Open: Day 3 Media Notes

MOSELLE OPEN: DAY 3 MEDIA NOTES Wednesday, September 21, 2016 Les Arénes de Metz, Metz, France | September 19-25, 2016 Draw: S-28, D-16 | Prize Money: €463,520 | Surface: Indoor Hard ATP World Tour Info Tournament Info ATP PR & Marketing www.ATPWorldTour.com www.Moselle-Open.com Stephanie Natal: [email protected] Twitter: @ATPWorldTour Twitter: @MoselleOpen Press Room: +33 372 60 5850 Facebook: @ATPWorldTour Facebook: @MoselleOpen THIEM MAKES DEBUT, ROBREDO RETURNS TO ACTION DAY 3 PREVIEW: There are five remaining first round matches and three second round matches on Wednesday’s schedule at the Moselle Open. Leading the way is top seed Dominic Thiem, who makes his tournament debut and 2007 champion Tommy Robredo, who returns from an elbow injury which has sidelined him from the ATP World Tour since March. In the opening match on Court Patrice Dominguez, German Davis Cup hero Jan-Lennard Struff takes on Robredo in a first round match. Struff won the fifth and decisive match Sunday over Poland’s Hurkacz to lift Germany to a 3-2 Davis Cup win and into the World Group next year. Struff advanced to the semi-finals here two years ago in his previous Metz appearance. Robredo is 9-2 in Metz and he won the title in 2007 (d. No. 18 Murray). He also was a quarter-finalist in 2003 and in his last visit in 2010. Robredo underwent right elbow surgery on April 27 in Barcelona and has not played on the ATP World Tour since Dubai in late February due to the elbow injury. -

European Data Portal, 2016, Open Data Maturity in Europe

emini Consulting prepared this study as part of the European Data Portal project. The This report is the second in a series of annual studies and explores the level of Open Data Maturity in the EU28 and Norway, Switzerland and Liechtenstein – referred to as EU28+. The measurement is built on two key indicators Open Data Readiness and Portal Maturity, thereby covering the level of development of national activities promoting Open Data as well as the level of development of national portals. In 2016, with a 28.6% increase compared to 2015, the EU28+ countries completed over 55% of their Open Data journey showing that, by 2016, a majority of the EU28+ countries have successfully developed a basic approach to address Open Data. The Portal Maturity level increased by 22.6 percentage points from 41.7% to 64.3% thanks to the development of more advanced features on country data portals. The overall Open Data Maturity groups countries into different clusters: Beginners, Followers, Fast Trackers and Trend Setters. Barriers do remain to move Open Data forward. The report concludes on a series of recommendations, providing countries with guidance to further improve Open Data maturity. Countries need to raise more (political) awareness around Open Data, increase automated processes on their portals to increase usability and re-usability of data, and organise more events and trainings to support both local and national initiatives. Résumé Ce rapport est le second d’une série de rapports annuels et explore le niveau de maturité « Open Data » des 28 pays de l’UE ainsi que les pays de l’Association européenne de libre-échange (AELE), dénommés UE28+. -

Annual Report 2015 International Paralympic Committee 2 Annual Report 2015

International Paralympic Committee Annual Report 2015 International Paralympic Committee 2 Annual Report 2015 Images (c) Photo Credits: Getty Images (1, 4, 5, 8, 9, 14, 15, 18, 20, 28, 46, 47, 60, 61, 66, 67, 80, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90), James Netz Photography (2, 3, 39, 68, 69, 89, 91), IPC (5, 26, 88, 90), Maroma (7, 28, 29, 51), Marcelo Regua (12, 13), Rio 2016 (16, 17), POCOG (18), Tokyo 2020 (20, 50), BWF (20, 89), NPC Colombia (22, 23), NPC Ecuador (27), Jon Blacker (30, 86), Richard Kaloscai (31, 89), Alpine Peak Photography Banff (34, 35, 64, 65, 87), Luc Percival (40, 76, 77, 86, 87, 88), Oriol Molas (52, 53, 78, 88), UN (54), Lieven Coudenys (55), Toyota (57, 85), Bill Wippert (70, 71, 88), Konstantin Kniazevych, Anatoly Kudyakov (72, 73, 90), NPC Chinese Taipei (79), Denis LeBreuilly (86), Carla Qualthrough (86), www.sa-images.com (87), Agitos Foundation (87), Jean-Baptiste Benavent, UCI (87), www.photo-hartmann.de (87), BP America (88), Hajni Valczer (88), Matko Mance (89), Finnish Sports Association of Persons with Disabilities (89), Peter Spurrier, Intersport Images (89), Dansk Handicap Idræts-Forbund (89), World Archery (89), ICF (89), CP England 2015 (90), Alina Pavlyuchik (90), Karl Nilsson (90), World Taekwondo Federation (90), Jon Stroud, FEI (90), LOC Rome (90), IBSA (90), Walter Cooper (90), Defi Sportif Altergo (90) International Paralympic Committee International Paralympic Committee Annual Report 2015 Annual Report 2015 3 President’s welcome 4 The Paralympic Movement and the IPC 8 Consolidating the Paralympic -

Len European Championships Aquatic Finalists

LEN EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIPS AQUATIC FINALISTS 1926-2016 2 EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIPS GLASGOW 2ND-12TH AUGUST 2018 SWIMMING AT TOLLCROSS INTERNATIONAL SWIMMING CENTRE DIVING AT ROYAL COMMONWEALTH POOL, EDINBURGH ARTISTIC (SYNCHRONISED) SWIMMING AT SCOTSTOUN SPORTS CAMPUS, GLASGOW OPEN WATER SWIMMING IN LAKE LOMOND 2 Contents Event Page Event Page European Championship Venues 5 4x100m Freestyle Team- Mixed 123 4x100m Medley Team – Mixed 123 50m Freestyle – Men 7 100m Freestyle – Men 9 Open Water Swimming – Medals Table 124 200m Freestyle – Men 13 400m Freestyle – Men 16 5km Open Water Swimming – Men 125 800m Freestyle – Men 20 10km Open Water Swimming – Men 126 1500m Freestyle – Men 21 25km Open Water Swimming – Men 127 50m Backstroke – Men 25 5km Open Water Swimming – Women 129 100m Backstroke – Men 26 10km Open Water Swimming – Women 132 200m Backstroke – Men 30 25km Open Water Swimming – Women 133 50m Breaststroke – Men 34 Open Water Swimming – Team 5km Race 136 100m Breaststroke – Men 35 200m Breaststroke – Men 38 Diving – Medals Table 137 50m Butterfly – Men 43 1m Springboard – Men 138 100m Butterfly – Men 44 3m Springboard – Men 140 200m Butterfly – Men 47 3m Springboard Synchro - Men 143 10m Platform – Men 145 200m Individual Medley – Men 50 10m Platform Synchro – Men 148 400m Individual Medley – Men 54 1m Springboard – Women 150 4x100m Freestyle Team – Men 58 3m Springboard – Women 152 4x200m Freestyle Team – Men 61 3m Springboard Synchro – Women 155 4x100m Medley Team – Men 65 10m Platform – Women 158 10m Platform Synchro – Women 161 -

2016 Rulebook 13Oct1149.Indd

The 2016 ATP® Offi cial Rulebook Copyright © 2016 by ATP Tour, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction of this work in whole or in part without the written per- mission of the ATP Tour, Inc., is prohibited. Printed in the United States of America. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. ATP CIRCUIT REGULATIONS ...............................7 1.01 Categories of Tournaments ...................................................................... 7 1.02 Tournament Week ..................................................................................... 7 1.03 Match Schedule Plan ............................................................................... 8 1.04 Finals Options ........................................................................................... 8 1.05 Change of Tournament Site ....................................................................... 9 1.06 Commitment to Rules ................................................................................ 9 1.07 Commitment, Membership Obligations and Bonus Pool ........................... 9 1.08 Reduction of ATP World Tour Masters 1000 Commitment ...................... 12 1.09 Unsatisfi ed Player Commitment Penalties .............................................. 13 1.10 Mandatory Player Meeting ...................................................................... 13 1.11 Player Eligibility/Player University/Physical Exam ................................... 14 1.12 Waiver of Claims ..................................................................................... 14 1.13 Waiver/Player -

2016 Immaf European Open Championships of Amateur

2016 IMMAF EUROPEAN OPEN CHAMPIONSHIPS OF AMATEUR MMA HANDBOOK Version 1.2 August 22nd 2016 2 Contents 1 – Organizer 2 – Program 3 - Competition Place 4 – Eligibility 5 – Participation 6 – Categories 7 - Accreditation & Control of Nationality 8 - IMMAF Pre – Registration Online 9 – Key Deadlines 10 - Weigh in (inc allowance policy) & Pre Fight Medical Examination 11 - Competition Mode 12 – Draw 13 - Referees & Judges 14 – Corners (seconds), Team Leaders & Team Delegates 15 – Equipment 16 – Transport 17 – Accommodation 18 - Participation Fee 19 - Anti – Doping 20 - Medical Clearance 21 – Insurance of Competitors 22 – Media 23 – Visa 2 IMMAF 2016 European Open Handbook; Version 1.2 August 22nd 2016 3 1 – Organizer International Mixed Martial Arts Federation (IMMAF) Address: Regeringsgatan 109 111 39 Stockholm Sweden Email [email protected] Mixed Martial Arts Association Czech Republic V pláni 58/32 140 00 Praha 4 Lhotka Česká republika IČ: 22710876 Main contact for the host federation is Martin Skvara. Email: [email protected] Tel: +420 775 111 213 3 IMMAF 2016 European Open Handbook; Version 1.2 August 22nd 2016 4 IMMAF Hotel & Transport Contact Name: Gosha Malik Email: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0) 7939520461 Emergency Contact: Name: Alistair Pettitt Email: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0) 7900933329 Pre Event Support for Visa Applications: Name: Roberto Reid Email: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0) 7445810524 Record Enquiries: Name: Jorden Curran Email: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0) 7531457128 Medical Enquiries (SAFE MMA): Name: Yoni Gottlieb Email: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0) 7973321664 4 IMMAF 2016 European Open Handbook; Version 1.2 August 22nd 2016 5 2 – Program Attention: The schedule may be modified according to the total number of entries and circumstances of competition. -

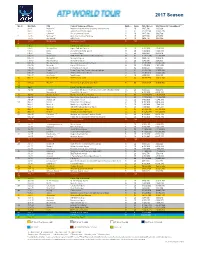

2017 ATP Calendar As of 2

2017 Season Week Start Date City Current Tournament Name Surface Draw Prize Money Total Financial Commitment** 1 Jan 1 Brisbane ¹ Brisbane International presented by Suncorp H 28$437,380 $495,630 Jan 2 Doha ⁷ Qatar ExxonMobil Open H 32$1,237,190 $1,334,270 Jan 2 Chennai Aircel Chennai Open H 28$447,480 $505,730 2 Jan 8 Sydney ¹ ̛ ⁷ Apia International Sydney H 28$437,380 $495,630 Jan 9 Auckland ⁷ ASB Classic H 28$450,110 $508,360 3Jan 16 Melbourne Australian Open* H 128 4 5 Feb 3 Davis Cup First Round* 6 Feb 6 Montpellier Open Sud de France IH 28€ 482,060 € 540,310 Feb 6 Sofia Garanti Koza Sofia Open IH 28€ 482,060 € 540,310 Feb 6 Quito Ecuador Open CL 28$482,060 $540,310 7 Feb 13 Rotterdam ABN AMRO World Tennis Tournament IH 32€ 1,724,930 € 1,854,365 Feb 13 Memphis Memphis Open IH 28$642,750 $720,410 Feb 13 Buenos Aires Argentina Open CL 28$546,680 $598,865 8 Feb 20 Rio de Janeiro Rio Open presented by Claro CL 32$1,461,560 $1,603,940 Feb 20 Marseille Open 13 Provence IH 28€ 620,660 € 691,850 Feb 20 Delray Beach Delray Beach Open H 32$534,625 $599,345 9 Feb 27 Dubai ⁷ Dubai Duty Free Tennis Championships H 32$2,429,150 $2,858,530 Feb 27 Acapulco ⁷ Abierto Mexicano Telcel H 32$1,491,310 $1,633,690 Feb 27 São Paulo Brasil Open CL 28$455,565 $520,285 10 Mar 9 Indian Wells ⁵ BNP Paribas Open H 96$6,993,450 $7,913,405 11 12 Mar 22 Miami ⁴ Miami Open presented by Itaú H 96$6,993,450 $7,913,405 13 14 Apr 7 Davis Cup Quarter-finals* 15 Apr 10 Houston Fayez Sarofim & Co. -

At Seascape Sports Club August 6 - 14, 2016

TEMPLATE_Men.1_Layout 1 12/11/15 4:04 PM Page 1 at Seascape Sports Club August 6 - 14, 2016 CATCH A RISING STAR TODAY! PROCIRCUIT.USTA.COM ©2016 USTA. All rights reserved. SEA-515 Sanderlings_Ad_FullPg_8.625x11.125_F_Layout 1 7/9/14 11:11 AM Page 1 At Sanderlings, the dining experience is as spectacular as the views — both indoors and out. ONE SEASCAPE RESORT DRIVE IN APTOS, ACROSS FROM SEASCAPE VILLAGE 831.662.7120 SANDERLINGSRESTAURANT.COM C NA DI TU R R O A N L S ® P r e K se N nt A ed B B y Y $ SA NT S 1 NT U O 00 A CRUZ CO T ,0 P 00 A Dear Friends, As longtime fans and supporters of the Challenger th tournament, Nordic Naturals is thrilled to be the title sponsor of this year’s event, now in its 29 year. The Nordic Naturals Challenger Tournament will once again bring world-‐class tennis to our area, to the delight of local tennis fans, dedicated sponsors, and our local community. As a leading manufacturer of omega-‐3s and other nutrients essential to health, Nordic Naturals understands and supports the unique nutritional needs of athletes—professional and amateur alike. We offer a select line of NSF Certified for Sport products that are used by many ATP touring pros, including 2014 Challenger champion and current No. 40 Marcos Baghdatis. Nordic Naturals is happy to give back to the amazing community that has supported our company since our founding here in 1995. We participate in a wide variety of local events and causes, among which the Challenger is a personal favorite. -

Player Biographies Active Players* Former Champions Open Era Winners

PLAYER BIOGRAPHIES ACTIVE PLAYERS* FORMER CHAMPIONS OPEN ERA WINNERS * TOP 100 SINGLES TOP 8 DOUBLES TEAMS TOP 200 #NEXTGENATP RADU ALBOT MDA @RaduAlbot @ RaduAlbot BORN: 11 November 1989, Chisinau, Moldova HEIGHT / WEIGHT: 1.75m (5'9") / 69kg (152lbs) RESIDENCE: Chisinau, Moldova PLAYS: Right-handed · Two-handed backhand CAREER W-L: 30-42 CAREER PRIZE MONEY: $1,268,479 CAREER W-L VS. TOP 10: 0-1 HIGHEST ATP RANKING: 81 (17 April 2017) CAREER 5TH-SET RECORD: 4-2 HIGHEST ATP DOUBLES RANKING: 68 (22 June 2015) 2017 HIGHLIGHTS PERSONAL > Favourite tournaments are US PRIZE MONEY: $488,359 > Some players gave him the Open and Wimbledon W-L: 9-17 (singles), 2-4 (doubles) nickname "Machine" > Idols growing up were Sebastien SINGLES QF (1): Antalya > Began playing tennis at age 8 Grosjean and Marat Safin because his father watched > If he was not a tennis player, he CAREER HIGHLIGHTS tennis on TV would have played football > Top-ranked Moldovan in ATP > Father, Vladimir, works at the > Enjoys spending time with Rankings history achieved ministry of internal affairs; friends and biking career-high No. 81 on 17 April mother, Svetlana, is a dentist > Studying at sports university in 2017 after reaching Marrakech > Speaks Romanian, Russian, Chisinau 2R. Broke into Top 100 on 27 July English and a bit of German and > Has trained in Romania, 2015 following run to Poznan, Spanish Germany, USA and Spain POL Challenger final. > Favourite surfaces are hard and clay > Coached by Liam Smith > Advanced to 1st ATP World Tour QF at 2017 Antalya. Captured 2015 Istanbul doubles title in YEAR-END ATP RANKINGS HISTORY (W-L) team debut w/Lajovic. -

ATP World Tour 2020 Schedule

ATP World Tour 2020 Schedule DATE TOURNAMENT SURFACE VENUE 6 January ATP Cup Hard Brisbane, Sydney, Perth, Australia Qatar Open Hard Doha, Qatar 13 January Adelaide International Hard Adelaide, Australia Auckland Open Hard Auckland, New Zealand 20 January Australian Open Hard Melbourne, Australia 3 February Open Sud de France Hard Montpellier, France Maharashtra Open Hard Pune, India Cordoba Open Clay (Red) Cordoba, Argentina 10 February Rotterdam Open Hard Rotterdam, Netherlands New York Open Hard Uniondale, United States Argentina Open Clay (Red) Buenos Aries, Argentina 17 February Rio Open Clay (Red) Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Open 13 Hard Marseille, France Delray Beach Open Hard Delray Beach, USA 24 February Dubai Tennis Championships Hard Dubai, UAE Mexican Open Hard Acapulco, Mexico Brasil Open Clay (RED) Sao Paulo, Brazil 9 March Indian Wells Masters Hard Indian Wells, USA 23 March Miami Open Hard Miami, USA 6 April U.S. Men's Clay Court Clay (Maroon) Houston, USA Championships Grand Prix Hassan II Clay (Red) Marrakesh, Morocco 13 April Monte-Carlo Masters Clay (Red) Monte-Carlo, Monaco 20 April Barcelona Open Clay (Red) Barcelona, Spain Hungarian Open Clay (Red) Budapest, Hungary 27 April Estoril Open Clay (Red) Estoril, Portugal Bavarian International Tennis Clay (Red) Munich, Germany Championships 4 May Madrid Open Clay (Red) Madrid, Spain 11 May Italian Open Clay (Red) Rome, Italy 18 May Geneva Open Clay (Red) Geneva, Switzerland Lyon Open Clay (Red) Lyon, France 25 May French Open Clay (Red) Paris, France 8 June Stuttgart Open