Nusinersen Use in Spinal Muscular Atrophy Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

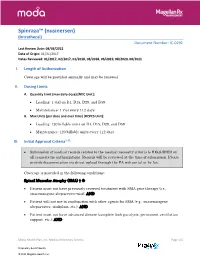

Spinraza™ (Nusinersen)

Spinraza™ (nusinersen) (Intrathecal) Document Number: IC-0291 Last Review Date: 08/03/2021 Date of Origin: 01/31/2017 Dates Reviewed: 01/2017, 02/2017, 01/2018, 08/2018, 06/2019, 08/2020, 08/2021 I. Length of Authorization Coverage will be provided annually and may be renewed. II. Dosing Limits A. Quantity Limit (max daily dose) [NDC Unit]: • Loading: 1 vial on D1, D15, D29, and D59 • Maintenance: 1 vial every 112 days B. Max Units (per dose and over time) [HCPCS Unit]: • Loading: 120 billable units on D1, D15, D29, and D59 • Maintenance: 120 billable units every 112 days III. Initial Approval Criteria1-12 • Submission of medical records related to the medical necessity criteria is REQUIRED on all requests for authorizations. Records will be reviewed at the time of submission. Please provide documentation via direct upload through the PA web portal or by fax. Coverage is provided in the following conditions: Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) † Ф • Patient must not have previously received treatment with SMA gene therapy (i.e., onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi); AND • Patient will not use in combination with other agents for SMA (e.g., onasemnogene abeparvovec, risdiplam, etc.); AND • Patient must not have advanced disease (complete limb paralysis, permanent ventilation support, etc.); AND Moda Health Plan, Inc. Medical Necessity Criteria Page 1/5 Proprietary & Confidential © 2021 Magellan Health, Inc. • Patient must have the following laboratory tests at baseline and prior to each administration*: platelet count, prothrombin time; activated -

FDA and Marijuana: Questions and Answers 1

FDA and Marijuana: Questions and Answers 1. How is marijuana therapy being used by some members of the medical community? A. The FDA is aware that marijuana or marijuana-derived products are being used for a number of medical conditions including, for example, AIDS wasting, epilepsy, neuropathic pain, treatment of spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis, and cancer and chemotherapy-induced nausea. 2. Why hasn’t the FDA approved marijuana for medical uses? A. To date, the FDA has not approved a marketing application for marijuana for any indication. The FDA generally evaluates research conducted by manufacturers and other scientific investigators. Our role, as laid out in the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act, is to review data submitted to the FDA in an application for approval to assure that the drug product meets the statutory standards for approval. The FDA has approved Epidiolex, which contains a purified drug substance cannabidiol, one of more than 80 active chemicals in marijuana, for the treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or Dravet syndrome in patients 2 years of age and older. That means the FDA has concluded that this particular drug product is safe and effective for its intended indication. The agency also has approved Marinol and Syndros for therapeutic uses in the United States, including for the treatment of anorexia associated with weight loss in AIDS patients. Marinol and Syndros include the active ingredient dronabinol, a synthetic delta-9- tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) which is considered the psychoactive component of marijuana. Another FDA-approved drug, Cesamet, contains the active ingredient nabilone, which has a chemical structure similar to THC and is synthetically derived. -

2017 ANNUAL REPORT | Translating SCIENCE • Transforming LIVES OUR COMMITMENT Make Every Day Count at PTC, Patients Are at the Center of Everything We Do

20 YEARS OF COMMITMENT 2017 ANNUAL REPORT | Translating SCIENCE • Transforming LIVES OUR COMMITMENT Make every day count At PTC, patients are at the center of everything we do. We have the opportunity to support patients and families living with rare disorders through their journey. We know that every day matters and we are committed to making a difference. OUR SCIENCE Our scientists are finding new ways to regulate biology to control disease We have several scientific research platforms focused on modulating protein expression within the cell that we believe have the potential to address many rare genetic disorders. OUR PEOPLE Care for each other, our community, and for the needs of our patients At PTC, we are looking at drug discovery and development in a whole new light, bringing new technologies and approaches to developing medicines for patients living with rare disorders and cancer. We strive every day to be better than we were the day before. At PTC Therapeutics, it is our mission to provide access to best-in-class treatments for patients who have an unmet need. We are a science-led, global biopharmaceutical company focused on the discovery, development and commercialization of clinically-differentiated medicines that provide benefits to patients with rare disorders. Founded 20 years ago, PTC Therapeutics has successfully launched two rare disorder products and has a global commercial footprint. This success is the foundation that drives investment in a robust pipeline of transformative medicines and our mission to provide access to best-in-class treatments for patients who have an unmet medical need. As we celebrate our 20th year of bringing innovative therapies to patients affected by rare disorders, we reflect on our unwavering commitment to our patients, our science and our employees. -

FDA Comments on CBD in Foods

Popular Content Public Health Focus FDA and Marijuana: Questions and Answers 1. How is marijuana therapy being used by some members of the medical community? 2. Why hasn’t the FDA approved marijuana for medical uses? 3. Is marijuana safe for medical use? 4. How does FDA’s role differ from NIH and DEA’s role when it comes to the investigation of marijuana for medical use? 5. Does the FDA object to the clinical investigation of marijuana for medical use? 6. What kind of research is the FDA reviewing when it comes to the efficacy of marijuana? 7. How can patients get into expanded access program for marijuana for medical use? 8. Does the FDA have concerns about administering a cannabis product to children? 9. What is FDA’s reaction to states that are allowing marijuana to be sold for medical uses without the FDA’s approval? 10. What is the FDA’s position on state “Right to Try” bills? 11. Has the agency received any adverse event reports associated with marijuana for medical conditions? 12. Can products that contain cannabidiol be sold as dietary supplements? 13. Is it legal, in interstate commerce, to sell a food to which cannabidiol has been added? 14. In making the two previous determinations, why did FDA conclude that substantial clinical investigations have been authorized for and/or instituted about cannabidiol, and that the existence of such investigations has been made public? 15. Will FDA take enforcement action regarding cannabidiol products that are marketed as dietary supplements? What about foods to which cannabidiol has been added? 16. -

Spinraza® (Nusinersen)

UnitedHealthcare® Commercial Medical Benefit Drug Policy Spinraza® (Nusinersen) Policy Number: 2021D0059I Effective Date: July 1, 2021 Instructions for Use Table of Contents Page Community Plan Policy Coverage Rationale ....................................................................... 1 • Spinraza® (Nusinersen) Documentation Requirements ...................................................... 3 Applicable Codes .......................................................................... 3 Background.................................................................................... 4 Benefit Considerations .................................................................. 5 Clinical Evidence ........................................................................... 5 U.S. Food and Drug Administration ............................................. 8 References ..................................................................................... 9 Policy History/Revision Information ........................................... 10 Instructions for Use ..................................................................... 11 Coverage Rationale See Benefit Considerations Spinraza® (nusinersen) is proven and medically necessary for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in patients who meet all of the following criteria: 1-4,22,23 Initial Therapy Diagnosis of spinal muscular atrophy by, or in consultation with, a neurologist with expertise in the diagnosis of SMA; and Submission of medical records (e.g., chart notes, laboratory values) -

DRUGS REQUIRING PRIOR AUTHORIZATION in the MEDICAL BENEFIT Page 1

Effective Date: 08/01/2021 DRUGS REQUIRING PRIOR AUTHORIZATION IN THE MEDICAL BENEFIT Page 1 Therapeutic Category Drug Class Trade Name Generic Name HCPCS Procedure Code HCPCS Procedure Code Description Anti-infectives Antiretrovirals, HIV CABENUVA cabotegravir-rilpivirine C9077 Injection, cabotegravir and rilpivirine, 2mg/3mg Antithrombotic Agents von Willebrand Factor-Directed Antibody CABLIVI caplacizumab-yhdp C9047 Injection, caplacizumab-yhdp, 1 mg Cardiology Antilipemic EVKEEZA evinacumab-dgnb C9079 Injection, evinacumab-dgnb, 5 mg Cardiology Hemostatic Agent BERINERT c1 esterase J0597 Injection, C1 esterase inhibitor (human), Berinert, 10 units Cardiology Hemostatic Agent CINRYZE c1 esterase J0598 Injection, C1 esterase inhibitor (human), Cinryze, 10 units Cardiology Hemostatic Agent FIRAZYR icatibant J1744 Injection, icatibant, 1 mg Cardiology Hemostatic Agent HAEGARDA c1 esterase J0599 Injection, C1 esterase inhibitor (human), (Haegarda), 10 units Cardiology Hemostatic Agent ICATIBANT (generic) icatibant J1744 Injection, icatibant, 1 mg Cardiology Hemostatic Agent KALBITOR ecallantide J1290 Injection, ecallantide, 1 mg Cardiology Hemostatic Agent RUCONEST c1 esterase J0596 Injection, C1 esterase inhibitor (recombinant), Ruconest, 10 units Injection, lanadelumab-flyo, 1 mg (code may be used for Medicare when drug administered under Cardiology Hemostatic Agent TAKHZYRO lanadelumab-flyo J0593 direct supervision of a physician, not for use when drug is self-administered) Cardiology Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension EPOPROSTENOL (generic) -

Regulating Rare Disease: Safely Facilitating Access to Orphan Drugs

Fordham Law Review Volume 86 Issue 4 Article 15 2018 Regulating Rare Disease: Safely Facilitating Access to Orphan Drugs Julien B. Bannister Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Recommended Citation Julien B. Bannister, Regulating Rare Disease: Safely Facilitating Access to Orphan Drugs, 86 Fordham L. Rev. 1889 (2018). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol86/iss4/15 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regulating Rare Disease: Safely Facilitating Access to Orphan Drugs Erratum Law; Administrative Law; Agency; Legislation; Food and Drug Law; Medical Jurisprudence; Law and Society This note is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol86/iss4/15 NOTES REGULATING RARE DISEASE: SAFELY FACILITATING ACCESS TO ORPHAN DRUGS Julien B. Bannister* While approximately one in ten Americans suffers from a rare disease, only 5 percent of rare diseases have a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved treatment. Congressional and regulatory efforts to stimulate the development of rare-disease treatments, while laudable, have not resolved the fundamental issues surrounding rare-disease treatment development. Indeed, small patient populations, incomplete scientific understanding of rare diseases, and high development costs continually limit the availability of rare-disease treatments. To illustrate the struggle of developing and approving safe rare-disease treatments, this Note begins by discussing the approval of Eteplirsen, the first drug approved for treating a rare disease called Duchenne muscular dystrophy. -

New Brunswick Drug Plans Formulary

New Brunswick Drug Plans Formulary August 2019 Administered by Medavie Blue Cross on Behalf of the Government of New Brunswick TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction.............................................................................................................................................I New Brunswick Drug Plans....................................................................................................................II Exclusions............................................................................................................................................IV Legend..................................................................................................................................................V Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification of Drugs A Alimentary Tract and Metabolism 1 B Blood and Blood Forming Organs 23 C Cardiovascular System 31 D Dermatologicals 81 G Genito Urinary System and Sex Hormones 89 H Systemic Hormonal Preparations excluding Sex Hormones 100 J Antiinfectives for Systemic Use 107 L Antineoplastic and Immunomodulating Agents 129 M Musculo-Skeletal System 147 N Nervous System 156 P Antiparasitic Products, Insecticides and Repellants 223 R Respiratory System 225 S Sensory Organs 234 V Various 240 Appendices I-A Abbreviations of Dosage forms.....................................................................A - 1 I-B Abbreviations of Routes................................................................................A - 4 I-C Abbreviations of Units...................................................................................A -

Prescription Drugs Requiring Prior Authorization

PRESCRIPTION DRUGS REQUIRING PRIOR AUTHORIZATION Revised 10/16 As part of our drug utilization management program, members must request and receive prior authorization for certain prescription drugs in order to use their prescription drug benefits. Below is a list of drugs that currently require prior authorization. This list will be updated periodically as new drugs that require prior authorization are introduced. As benefits may vary by group and individual plans, the inclusion of a medication on this list does not imply prescription drug coverage. The Schedule of Benefits contains a list of drug categories that require prior authorization. Prior authorization requests are processed by our pharmacy benefit manager, Express Scripts, Inc. (ESI). Physicians must call ESI to obtain an authorization. (1-800-842-2015). Drug Name Generic Name Drug Classification Abstral fentanyl citrate oral tablet Controlled Dangerous Substance Accu-Chek Test Strips blood glucose test strips Blood Glucose Test Strips Actemra tocilizumab Monoclonal Antibody Acthar corticotropin Hormone Actimmune interferon gamma 1b Interferon Actiq fentanyl citrate OTFC Controlled Dangerous Substance Adcirca tadalafil Pulmonary Vasodilator Adempas riociguat Pulmonary Vasodilator Adlyxin lixisenatide Type 2 Diabetes Advocate Test Strips blood glucose test strips Blood Glucose Test Strips Aerospan** flunisolide Corticosteroids (Inhaled) Afrezza insulin Insulin (inhaled) Ampyra dalfampridine Multiple Sclerosis Agent Altoprev** lovastatin Cholesterol Alvesco** ciclesonide Corticosteroids -

Circulating Biomarkers in Neuromuscular Disorders: What Is Known, What Is New

biomolecules Review Circulating Biomarkers in Neuromuscular Disorders: What Is Known, What Is New Andrea Barp 1,* , Amanda Ferrero 1, Silvia Casagrande 1,2 , Roberta Morini 1 and Riccardo Zuccarino 1 1 NeuroMuscular Omnicentre (NeMO) Trento, Villa Rosa Hospital, Via Spolverine 84, 38057 Pergine Valsugana, Italy; [email protected] (A.F.); [email protected] (S.C.); [email protected] (R.M.); [email protected] (R.Z.) 2 Department of Neurosciences, Drug and Child Health, University of Florence, Largo Brambilla 3, 50134 Florence, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The urgent need for new therapies for some devastating neuromuscular diseases (NMDs), such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, has led to an intense search for new potential biomarkers. Biomarkers can be classified based on their clinical value into different categories: diagnostic biomarkers confirm the presence of a specific disease, prognostic biomarkers provide information about disease course, and therapeutic biomarkers are designed to predict or measure treatment response. Circulating biomarkers, as opposed to instrumental/invasive ones (e.g., muscle MRI or nerve ultrasound, muscle or nerve biopsy), are generally easier to access and less “time-consuming”. In addition to well-known creatine kinase, other promising molecules seem to be candidate biomarkers to improve the diagnosis, prognosis and prediction of therapeutic response, such as antibodies, neurofilaments, and microRNAs. However, there are some criticalities that can complicate their application: variability during the day, stability, and reliable performance metrics Citation: Barp, A.; Ferrero, A.; (e.g., accuracy, precision and reproducibility) across laboratories. In the present review, we discuss Casagrande, S.; Morini, R.; Zuccarino, the application of biochemical biomarkers (both validated and emerging) in the most common NMDs R. -

Federal Register/Vol. 74, No. 155/Thursday, August 13, 2009

40900 Federal Register / Vol. 74, No. 155 / Thursday, August 13, 2009 / Rules and Regulations addition to the direct costs described in Application which clarifies the efforts to expand access to paragraph (d)(1)(i) of this section, a circumstances in which charging for an investigational drugs for treatment use. sponsor may recover the costs of investigational drug in a clinical trial is Before 1987, there was no formal monitoring the expanded access IND or appropriate, sets forth criteria for recognition of treatment use in FDA’s protocol, complying with IND reporting charging for an investigational drug for regulations concerning INDs, but requirements, and other administrative the different types of expanded access investigational drugs were made costs directly associated with the for treatment use described in this final available for treatment use informally. expanded access IND. rule, and clarifies what costs can be In 1987, FDA revised the IND (3) To support its calculation for cost recovered for an investigational drug. regulations in part 312 (21 CFR part recovery, a sponsor must provide DATES: This rule is effective October 13, 312) to explicitly provide for one supporting documentation to show that 2009. specific kind of treatment use of the calculation is consistent with the FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: investigational drugs (52 FR 19466, May requirements of paragraphs (d)(1) and, if Colleen L. Locicero, Center for Drug 22, 1987). Section 312.34 authorized applicable, (d)(2) of this section. The Evaluation and Research, Food and access to investigational drugs for a documentation must be accompanied by Drug Administration, 10903 New broad population under a treatment a statement that an independent Hampshire Ave., Bldg. -

The Use of Ataluren in the Effective Management of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

Review Neuromuscular Diseases Early Diagnosis and Treatment – The Use of Ataluren in the Effective Management of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Eugenio Mercuri,1 Ros Quinlivan2 and Sylvie Tuffery-Giraud3 1. Catholic University, Rome, Italy; 2. Great Ormond Street Hospital and National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, UK; 3. Laboratory of Genetics of Rare Diseases (LGMR), University of Montpellier, Montpellier, France DOI: https://doi.org/10.17925/ENR.2018.13.1.31 he understanding of the natural history of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is increasing rapidly and new treatments are emerging that have the potential to substantially improve the prognosis for patients with this disabling and life-shortening disease. For many, Thowever, there is a long delay between the appearance of symptoms and DMD diagnosis, which reduces the possibility of successful treatment. DMD results from mutations in the large dystrophin gene of which one-third are de novo mutations and two-thirds are inherited from a female carrier. Roughly 75% of mutations are large rearrangements and 25% are point mutations. Certain deletions and nonsense mutations can be treated whereas many other mutations cannot currently be treated. This emphasises the need for early genetic testing to identify the mutation, guide treatment and inform genetic counselling. Treatments for DMD include corticosteroids and more recently, ataluren has been approved in Europe, the first disease-modifying therapy for treating DMD caused by nonsense mutations. The use of ataluren in DMD is supported by positive results from phase IIb and phase III studies in which the treatment produced marked improvements in the 6-minute walk test, timed function tests such as the 10 m walk/run test and the 4-stair ascent/descent test compared with placebo.