Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Thesis As a Partial Fulfillment Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Degas: Agency in Images of Women

Degas: Agency in Images of Women BY EMMA WOLIN Edgar Degas devoted much of his life’s work to the depiction of women. Among his most famous works are his ballet dancers, bathers and milliners; more than three- quarters of Degas’ total works featured images of women.1 Recently, the work of Degas has provoked feminist readings of the artist’s treatment of his subject matter. Degas began by sketching female relatives and eventually moved on to sketch live nude models; he was said to have been relentless in his pursuit of the female image. Some scholars have read this tendency as obsessive or pathological, while others trace Degas’ fixation to his own familial relationships; Degas’ own mother died when he was a teenager.2 Degas painted women in more diverse roles than most of his contemporaries. But was Degas a full-fledged misogynist? That may depend on one’s interpretation of his oeuvre. Why did he paint so many women? In any case, whatever the motivation and intent behind Degas’ images, there is much to be said for his portrayal of women. This paper will attempt to investigate Degas’ treatment of women through criticism, critical analysis, visual evidence and the author’s unique insight. Although the work of Degas is frequently cited as being misogynistic, some of his work gives women more freedom than they would have otherwise enjoyed, while other paintings, namely his nude sketches, placed women under the direct scrutiny of the male gaze. Despite the ubiquity 1 Richard Kendall, Degas, Images of Women, (London: Tate Gallery Publications, 1989), 11. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

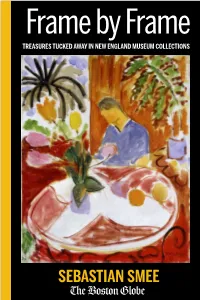

SEBASTIAN SMEE Abcde Introduction in ‘The Warrior,’ Dash and Virtuosity

Frame by Frame TReasURes TUCKED AWAY IN NEW ENGLAND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS SEBASTIAN SMEE abcde Introduction In ‘The Warrior,’ dash and virtuosity It seemed like a good idea at the time. It seems – and this is most unusual in my case – like an even better one now. As art critic at The Boston Globe, my brief is to review exhibitions in New England’s art mu- seums. Since I arrived at the Globe from Sydney, Australia, in 2008, I’ve been traveling to these shows as they open (or at least, in busy periods, before they shut!). But a good museum is about more than just its temporary exhibits. And so, whether I am go- ing to a show in Boston or farther afield, I always try to leave time to visit the permanent collec- tions of these museums, some of which are college museums (and what an abundance of excep- tional college art collections New England has!) while others are public museums with storied histories, such as the Peabody Essex Museum, the Boston Athenaeum, the Institute of Contempo- rary Art, or the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. After all, it’s the permanent collections that are, in almost every case, the great pride of these places, and of the communities they serve. From the very beginning, what I saw, as I traveled from Connecticut and Rhode Island to Maine and New Hampshire, blew me away. Four years later, I continue to marvel. The sheer range of art on display – from trumpeting masterpieces to small and whimsical improvisations – is stunning. And they’re all just waiting there, five, six, or seven days a week, in beautiful, spacious buildings that make it their business warmly to welcome the general public. -

Tang Teaching Museum Announces All Together Now

For immediate release Tang Teaching Museum announces All Together Now The Hyde Collection, Ellsworth Kelly Studio, National Museum of Racing Museum and Hall of Fame, Saratoga Arts, Saratoga County History Center, Saratoga Performing Arts Center, Shaker Museum, and Yaddo partner with the Tang at Skidmore College Collections sharing project supported by $275,000 Henry Luce Foundation grant SARATOGA SPRINGS, NY (April 1, 2021) — The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College announces an innovative regional collections sharing project called All Together Now, supported by a $275,000 grant from the Henry Luce Foundation. Organized by the Tang Teaching Museum, All Together Now forges new collaborations between neighbor arts organizations to bring attention to rarely seen works. At the Tang Teaching Museum, exhibitions will feature works from the Shaker Museum and Ellsworth Kelly Studio. At partner institutions, exhibitions will show work from the Tang collection, including many recently acquired paintings, photographs and sculptures. Partner institutions include The Hyde Collection, the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame, Saratoga Arts, Saratoga County History Center, Saratoga Performing Arts Center, and Yaddo. The grant will support these exhibitions, as well as the behind-the-scenes work that make the exhibitions possible, such as cataloging and digitizing Tang collection objects. “On behalf of the Tang and Skidmore College, I want to thank the Luce Foundation for their generosity and vision,” said Dayton Director Ian Berry. “This grant recognizes the vibrancy and relevance of the objects in our collection and gives all of us the rare opportunity to see important American artworks out of storage and in the public view, fostering new connections and conversations, and expanding knowledge. -

Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. Jessica Cresseveur University of Louisville

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 The queer child and haut bourgeois domesticity : Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. Jessica Cresseveur University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation Cresseveur, Jessica, "The queer child and haut bourgeois domesticity : Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt." (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2409. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2409 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE QUEER CHILD AND HAUT BOURGEOIS DOMESTICITY: BERTHE MORISOT AND MARY CASSATT By Jessica Cresseveur B.A., University of Louisville, 2000 M.A., University College London, 2003 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Comparative Humanities University -

Rise of Modernism

AP History of Art Unit Ten: RISE OF MODERNISM Prepared by: D. Darracott Plano West Senior High School 1 Unit TEN: Rise of Modernism STUDENT NOTES IMPRESSIONISM Edouard Manet. Luncheon on the Grass, 1863, oil on canvas Edouard Manet shocking display of Realism rejection of academic principles development of the avant garde at the Salon des Refuses inclusion of a still life a “vulgar” nude for the bourgeois public Edouard Manet. Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas Victorine Meurent Manet’s ties to tradition attributes of a prostitute Emile Zola a servant with flowers strong, emphatic outlines Manet’s use of black Edouard Manet. Bar at the Folies Bergere, 1882, oil on canvas a barmaid named Suzon Gaston Latouche Folies Bergere love of illusion and reflections champagne and beer Gustave Caillebotte. A Rainy Day, 1877, oil on canvas Gustave Caillebotte great avenues of a modern Paris 2 Unit TEN: Rise of Modernism STUDENT NOTES informal and asymmetrical composition with cropped figures Edgar Degas. The Bellelli Family, 1858-60, oil on canvas Edgar Degas admiration for Ingres cold, austere atmosphere beheaded dog vertical line as a physical and psychological division Edgar Degas. Rehearsal in the Foyer of the Opera, 1872, oil on canvas Degas’ fascination with the ballet use of empty (negative) space informal poses along diagonal lines influence of Japanese woodblock prints strong verticals of the architecture and the dancing master chair in the foreground Edgar Degas. The Morning Bath, c. 1883, pastel on paper advantages of pastels voyeurism Mary Cassatt. The Bath, c. 1892, oil on canvas Mary Cassatt mother and child in flattened space genre scene lacking sentimentality 3 Unit TEN: Rise of Modernism STUDENT NOTES Claude Monet. -

DOMESTIC LIFE and SURROUNDINGS: IMPRESSIONISM: (Degas, Cassatt, Morisot, and Caillebotte) IMPRESSIONISM

DOMESTIC LIFE and SURROUNDINGS: IMPRESSIONISM: (Degas, Cassatt, Morisot, and Caillebotte) IMPRESSIONISM: Online Links: Edgar Degas – Wikipedia Degas' Bellelli Family - The Independent Degas's Bellelli Family - Smarthistory Video Mary Cassatt - Wikipedia Mary Cassatt's Coiffure – Smarthistory Cassatt's Coiffure - National Gallery in Washington, DC Caillebotte's Man at his Bath - Smarthistory video Edgar Degas (1834-1917) was born into a rich aristocratic family and, until he was in his 40s, was not obliged to sell his work in order to live. He entered the Ecole des Beaux Arts in 1855 and spent time in Italy making copies of the works of the great Renaissance masters, acquiring a technical skill that was equal to theirs. Edgar Degas. The Bellelli Family, 1858-60, oil on canvas In this early, life-size group portrait, Degas displays his lifelong fascination with human relationships and his profound sense of human character. In this case, it is the tense domestic situation of his Aunt Laure’s family that serves as his subject. Apart from the aunt’s hand, which is placed limply on her daughter’s shoulder, Degas shows no physical contact between members of the family. The atmosphere is cold and austere. Gennaro, Baron Bellelli, is shown turned toward his family, but he is seated in a corner with his back to the viewer and seems isolated from the other family members. He had been exiled from Naples because of his political activities. Laure Bellelli stares off into the middle distance, significantly refusing to meet the glance of her husband, who is positioned on the opposite side of the painting. -

Synthesis: an Anglophone Journal of Comparative Literary Studies

Synthesis: an Anglophone Journal of Comparative Literary Studies Vol. 0, 2011 Capitalist Realism and the Refrain: The Libidinal Economies of Degas Philips Dougal https://doi.org/10.12681/syn.16921 Copyright © 2011 Dougal Philips To cite this article: Philips, D. (2011). Capitalist Realism and the Refrain: The Libidinal Economies of Degas. Synthesis: an Anglophone Journal of Comparative Literary Studies, 0(3), 69-81. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/syn.16921 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 26/09/2021 23:03:49 | Capitalist Realism and the Refrain: The Libidinal Economies of Degas Dougal Phillips Abstract This article looks to the work of Degas as an exemplar of a kind of Capitalist Realism, a kind of second generation realism following on from the earlier work of Courbet and Manet. It is posited here that Degas took up the mantle of a ‘corporeal’ realism distinguished from the Impressionists by its nuanced approach to the realism of the body, in particular to its place in the Parisian network of capital and desire. Degas’s paintings and his experiments with photography mapped two spaces: the space of the libidinal and capitalist exchange (theatre, café, stock-exchange) and the space of the production of painting. Further, Degas attempts to represent his own disappearance into both these spaces. Degas continued the politicised social project of realism but with a personalised, modernised vision that prefigures the realisms of the twentieth century. Introduction Among the realist painters of the later nineteenth century, the work of Hilaire-Germaine-Edgar Degas stands out as singularly concerned with the multi-layered spaces of the social field. -

Annual Report 1974

nnua ANNUAL REPORT 1974 NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 70-173826. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D C. 20565. Copyright © 797J Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art Frontispiece: The Pistoia Crucifix, Pietro Tacca, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, detail THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART The Chief Justice, The Secretary of State, The Secretary of the Treasur Warren E. Burger Henry A. Kiss in get- William E. Simon & John Hay Whitney, Carlisle H. Humelsine Franklin D. Murphy Stoddard M. Stevens Vice-President 6 CONTENTS 7 ORGANIZATION 9 DIRECTOR'S REVIEW OF THE YEAR 26 APPROPRIATIONS 27 CURATORIAL ACTIVITIES 27 Acquisitions 47 Donors of Works of Art 48 Lenders 51 Exhibitions and Loans 60 REPORTS OF PROFESSIONAL DEPARTMENTS 60 Library 61 Photographic Archives 62 Graphic Arts Department 63 Education Department 65 Art Information Service 65 Editor's Office 66 Publications 66 Conservation 68 Photographic Services 69 OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY AND GENERAL COUNSEL 70 STAFF ACTIVITIES AND PUBLICATIONS 76 ADVANCED STUDY AND RESEARCH 76 Kress Professor in Residence 76 National Gallery Fellows 78 NATIONAL PROGRAMS 78 Extension Service 79 Art and Man 79 Index of American Design 80 REPORT OF THE ADMINISTRATOR 80 Attendance 80 Building 81 Employees 83 MUSIC AT THE GALLERY 87 EAST BUILDING ORGANIZATION The 37th annual report of the National Gallery of Art reflects another year of continuing growth and change. Although for- mally established by Congress as a bureau of the Smithsonian Institu- tion, the National Gallery is an autonomous and separately admin- istered organization and is governed by its own Board of Trustees. -

Mcnay ART MUSEUM 2013 | 2015 Annual Report Visitors Enjoy a Free Family John and Peg Emley with Bill Chiego at the Margaritaville at the Day at the Mcnay

McNAY ART MUSEUM 2013 | 2015 Annual Report Visitors enjoy a free family John and Peg Emley with Bill Chiego at the Margaritaville at the day at the McNay. McNay Spring Party. Lesley Dill and René Paul Barilleaux, Chief Curator/Curator of Contemporary Art, at the Opening of Lesley Dill: Performance as Art. McNay Second Thursday band plays indie tunes on the Brown Sculpture Terrace. Visitors enjoy a free family day at the McNay. Emma and Toby Calvert at the 60th Sarah E. Harte and John Gutzler at the 60th Anniversary Celebration Anniversary Celebration Visitor enjoys field day activities during a free A local food truck serves up delicious dishes at McNay Second Suhail Arastu at the McNay Gala Hollywood Visions: Dressing the Part. family day at the McNay. Thursdays. Table of Contents Board of Trustees As of December 31, 2015 Letter from the President ................................................................................4 Tom Frost, Chairman Sarah E. Harte, President Letter from the Director ...................................................................................5 Connie McCombs McNab, Vice President Museum Highlights ...........................................................................................6 Lucille Oppenheimer Travis, Secretary Barbie O’Connor, Treasurer Notable Staff Accomplishments ...................................................................10 Toby Calvert Acquisitions ..........................................................................................................13 John W. Feik -

2014 International 14.01.2014 > 30.03.2014 Art Exhibitions 2014

International 01 Art Exhibitions 2014 International 14.01.2014 > 30.03.2014 Art Exhibitions 2014 Piero della Francesca Personal Encounters The Metropolitan Museum of Art Metropolitan The Opposite page Madonna and Child with Two Angels c1464-74, Tempera and oil on wood (walnut) 62.7 x 52.8 cm Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Palazzo Ducale, Urbino 1 Saint Jerome and a Supplicant c1460-64, Tempera and oil on wood 49.4 x 42 cm 1 Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice Through a special collaboration with 2 the Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice, and Madonna and Child the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, c1439-40, Tempera on Urbino, The Metropolitan Museum of panel Art is hosting a focused presentation of 53 x 41 cm four devotional paintings by Piero della The Alana Collection, Francesca. These are works painted in Delaware tempera on canvas, intended for private 3 prayer, some featuring portraits of the Saint Jerome patrons who commissioned them. in the Wilderness As the four works on view have never 1450, Tempera and oil before been brought together; the on wood (chestnut) exhibition promises to facilitate an 51 x 38 cm New York important contribution to the study of Gemäldegalerie, Piero della Francesca – a major figure of Staatliche Museen the Renaissance. 2 zu Berlin The four paintings are ‘Saint Jerome and There’s a precise mathematical study a Supplicant’, ‘Madonna and Child with underlying his work, and much has two Angels (the Senigallia Madonna)’, been said of his use of the Golden Mean. ‘Saint Jerome in a Landscape’ and His work features remarkable psycho- ‘Madonna and Child’. -

Annual Report 2013

N A TIO NAL G ALL E R Y O F A R T 2013 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION Louise Bryson BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEE Vincent J. Buonanno (as of 30 September 2013) Victoria P. Sant W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Chairman Calvin Cafritz Earl A. Powell III Louisa Duemling Frederick W. Beinecke Barney A. Ebsworth Mitchell P. Rales Gregory W. Fazakerley Sharon P. Rockefeller Doris Fisher Andrew M. Saul Aaron I. Fleischman Marina Kellen French FINANCE COMMITTEE Morton Funger Mitchell P. Rales Rose Ellen Greene Chairman Frederic C. Hamilton Jacob J. Lew Teresa Heinz Secretary of the Treasury Benjamin R. Jacobs Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Victoria P. Sant Betsy K. Karel Sharon P. Rockefeller Chairman President Linda H. Kaufman Victoria P. Sant Mark J. Kington Andrew M. Saul Robert L. Kirk Jo Carole Lauder AUDIT COMMITTEE Leonard A. Lauder Frederick W. Beinecke LaSalle D. Leffall Jr. Chairman Edward J. Mathias Mitchell P. Rales Robert B. Menschel Sharon P. Rockefeller Diane A. Nixon Victoria P. Sant Tony Podesta Andrew M. Saul Frederick W. Beinecke Mitchell P. Rales Diana C. Prince Robert M. Rosenthal TRUSTEES EMERITI Roger W. Sant Robert F. Erburu B. Francis Saul II Julian Ganz, Jr. Fern M. Schad Alexander M. Laughlin Michelle Smith David O. Maxwell Luther M. Stovall John Wilmerding Ladislaus von Hoffmann Christopher V. Walker EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Diana Walker Victoria P. Sant Alice L. Walton President Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Walter L. Weisman Chief Justice of the Earl A. Powell III Director Andrea Woodner United States Franklin Kelly Deputy Director and HONORARY TRUSTEES’ Chief Curator COUNCIL William W.