Gerner on Berend, 'History in My Life: a Memoir of Three Eras'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paris: a Love Story by Kati Marton Book

Paris: A Love Story by Kati Marton book Ebook Paris: A Love Story currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Paris: A Love Story please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Paperback:::: 224 pages+++Publisher:::: Simon & Schuster; Reprint edition (March 12, 2013)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 1451691556+++ISBN-13:::: 978-1451691559+++Product Dimensions::::5.5 x 0.6 x 8.4 inches++++++ ISBN10 1451691556 ISBN13 978-1451691 Download here >> Description: This New York Times bestseller is a memoir for anyone who has ever fallen in love in Paris or with Paris.This is a memoir for anyone who has ever fallen in love in Paris, or with Paris.PARIS: A LOVE STORY is for anyone who has ever had their heart broken or their life upended.In this remarkably honest and candid memoir, award-winning journalist and distinguished author Kati Marton narrates an impassioned and romantic story of love, loss, and life after loss. Paris is at the heart of this deeply moving account. Marton paints a vivid portrait of an adventuresome life in the stream of history. Inspirational and deeply human, Paris: A Love Story will touch every generation. This is an enjoyable summer read, but I had very definite deja vu to 40 years ago and reading the autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini in college. Both Cellini and Marton are engaging writers, but their almost psychopathic egotism makes for an interesting, if at times, exasperating experience. One of the reasons famous peoples biographies are more interesting is because most of us are curious to see behind the curtains of the rich and powerful. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Hungary: the Assault on the Historical Memory of The

HUNGARY: THE ASSAULT ON THE HISTORICAL MEMORY OF THE HOLOCAUST Randolph L. Braham Memoria est thesaurus omnium rerum et custos (Memory is the treasury and guardian of all things) Cicero THE LAUNCHING OF THE CAMPAIGN The Communist Era As in many other countries in Nazi-dominated Europe, in Hungary, the assault on the historical integrity of the Holocaust began before the war had come to an end. While many thousands of Hungarian Jews still were lingering in concentration camps, those Jews liberated by the Red Army, including those of Budapest, soon were warned not to seek any advantages as a consequence of their suffering. This time the campaign was launched from the left. The Communists and their allies, who also had been persecuted by the Nazis, were engaged in a political struggle for the acquisition of state power. To acquire the support of those Christian masses who remained intoxicated with anti-Semitism, and with many of those in possession of stolen and/or “legally” allocated Jewish-owned property, leftist leaders were among the first to 1 use the method of “generalization” in their attack on the facticity and specificity of the Holocaust. Claiming that the events that had befallen the Jews were part and parcel of the catastrophe that had engulfed most Europeans during the Second World War, they called upon the survivors to give up any particularist claims and participate instead in the building of a new “egalitarian” society. As early as late March 1945, József Darvas, the noted populist writer and leader of the National Peasant -

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards

2010 dateline SPECIAL EDITION CARACAS, VENEZUELA WINNERS OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB AWARDS dateline 2010 1 LETTERFROM THE PRESIDENT t the Overseas Press Club of America, we are marching through our 71st year insisting that fact-based, hard-news reporting from abroad is more important than ever. As we salute the winners of our 20 awards, I am proud to say their work is a tribute to the public’s right to know. As new forms of communication erupt, the incessant drumbeat of the A24-hour news cycle threatens to overwhelm the public desire for information by swamping readers and viewers with instant mediocrity. Our brave winners – and IS PROUD the news organizations that support them – reject the temptation to oversimplify, trivialize and then abandon important events as old news. For them, and for the OPC, the earthquakes in Haiti and Chile, the shifting fronts in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq, the drug wars of Mexico and genocides and commodity grabs in Africa need to be covered thoroughly and with integrity. TO SUPPORT The OPC believes quality journalism will create its own market. In spite of the decimation of the traditional news business, worthwhile journalism can and will survive. Creators of real news will get paid a living wage and the young who desire to quest for the truth will still find journalism viable as a proud profession and a civic good. We back that belief with our OPC Foundation, which awards 12 scholarships a year to deserving students who express their desire to become foreign correspondents while submitting essays on international subjects. -

Amnesty International Group 22 Pasadena/Caltech News Volume XIX Number 8, August 2011 Next Rights Readers UPCOMING EVENTS Meeting: Thursday, August 25, 7:30 PM

Amnesty International Group 22 Pasadena/Caltech News Volume XIX Number 8, August 2011 Next Rights Readers UPCOMING EVENTS meeting: Thursday, August 25, 7:30 PM. Monthly Sunday, Sept. 18, 6:30 PM Meeting. Note new location at Avery Center. See Coordinator’s Column for more info. Vroman’s Bookstore Help us plan future actions on Sudan, the 695 E. Colorado Boulevard ‘War on Terror’, death penalty and more. In Pasadena Tuesday, September 13, 7:30 PM. Letter writing meeting at Caltech Athenaeum, corner Enemies of the People of Hill and California in Pasadena. This By Kati Marton informal gathering is a great way for newcomers to get acquainted with Amnesty! Sunday, September 18, 6:30PM. Rights About the Author Readers Human Rights Book Discussion group. This month we read “Enemies of the Kati Marton, an award- People” by Kati Marton. winning former NPR and ABC News correspondent, is the author of Hidden Power: COORDINATOR’S CORNER Presidential Marriages That Hi everyone Shaped Our History, a New York Times bestseller, as Thanks a million to Lucas, Joyce, and Stevi for well as Wallenberg, The Polk doing the coordinator’s column and putting the Conspiracy, A Death in newsletter together for July. It looked great! We Jerusalem, and a novel, An American Woman. were on vacation, a combo plane and car trip to Mother of a son and a daughter, she lives in the Southeastern US. We had a great time and New York and was married to Richard visited 10 cities and 7 states in 12 days! High- Holbrook. lights were the swamp tour in Louisiana, the Smokey Mountains National Park (mama and BOOK REVIEW by ALAN FURST bear cubs sighting!!), the Emerald Coast of Published: October 30, 2009,New York Times Florida, Savannah, Georgia and Charleston, S. -

Annual Report 2009-2010

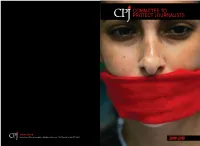

COMMITTEE TO PROTECT JOURNALISTS www.cpj.org Committee to Protect Journalists • 330 Seventh Avenue, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10001 2009-2010 Committee to Protect Journalists I LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR The Committee to Protect Journalists promotes media freedom worldwide. We take action when journalists are censored, jailed, kidnapped, or killed for their work. CPJ is an independent, nonprofit organization founded in 1981. REUTERS/YURIKO NAKAO REUTERS/YURIKO Dear Friends: This is an incredibly exciting time to be defending independent journalists and free expression. Digital technologies are enabling new forms of journalism and contributing to a global culture of greater open- ness and transparency. There are more people practicing journalism than ever before. The new technologies, however, can be a boon to repressive governments—allowing for surveillance and censorship on an unprecedented scale. In 2009, half of all imprisoned journalists were targeted for work published online. The Internet is also transforming the news business, which has enormous implications for our work. As media companies eliminate foreign bureaus and cut staff positions, freelancers are on the front- lines of reporting the news around the world. Freelance journalists are especially vulnerable to arrest and intimidation because they often lack the legal and financial support that large news organizations can provide to staffers. Journalists of all stripes increasingly work independently—that is to say, alone. These trends make CPJ’s work even more vitally important. When journalists are imprisoned, we campaign for their release. When journalists are forced into exile, we help support them. When jour- nalists are killed for their work, we demand justice. -

Zsuzsanna Lápossy Diosy

Eva Livia Corredor. East-West Odyssey. Self Published, 2008. Pp. 275, illus.; Zsuzsanna Lápossy Diosy. Life behind the Iron Curtain. Self Published, 2006. No page no., illus.; Kati Marton. Enemies of the People. My Family’s Journey to North America. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009. pp. 272, illus. Reviewed by Enikő M. Basa, Library of Congress. Three books, three totally different life stories, yet each a memoir of the Second World War and its aftermath. In East West Odyssey the author‟s focus is on her career in the United States and fitting into American society years after her flight from Hungary. Enemies of the People tells a gripping story of how even privileged persons with good connections were hounded by the Communist government, while Life Behind the Iron Curtain chronicles what happened to ordinary people in post-war Hungary. Kati Marton‟s is the most professional and the best written. This is no surprise given her journalistic background, her access to primary sources beyond her own memory, and her impressive publisher support. While an academic with scholarly publications to her credit, Corredor‟s work suffers from not having had a strict editor. Unfortunately, the English version of Lápossy‟s work is almost unreadable because the translator was not at home in English and no competent editor reviewed the manuscript. What is a gripping story with flashes of vivid description is thus seriously marred. All three are memoirs but they are not equal. Marton is the child narrator whose comments are placed into context by the journalist. The tale, too, is not her own so much as that of her parents so that there is already a distancing. -

The Great Escape: Nine Jews Who Fled Hitler and Changed the World Pdf

FREE THE GREAT ESCAPE: NINE JEWS WHO FLED HITLER AND CHANGED THE WORLD PDF Kati Marton | 288 pages | 17 Mar 2008 | Simon & Schuster Ltd | 9780743261166 | English | London, United Kingdom Heroes from Hungary | by István Deák | The New York Review of Books Ilona Marton was a prize-winning journalist and political prisoner. As a correspondent for United Press, she covered the communist show-trials, including the trial of Cardinal Jozsef Mindszenty. Inshe and her journalist-husband Endre Marton were convicted on sham charges of The Great Escape: Nine Jews Who Fled Hitler and Changed the World for the United States. They served time in a maximum-security Hungarian The Great Escape: Nine Jews Who Fled Hitler and Changed the World and, after their release, filed stirring first-hand reports about the Hungarian uprising. Inthey were smuggled out of Hungary and were granted refugee status in the US. Little is known about Ilona Marton's early life. Her father reportedly "was a horse breeder whose frequent gambling losses were of great trepidation to the family. He once came home with a silver-tipped umbrella and announced that it was all the family owned. She raised her children as devout Roman Catholics and told them that their grandparents had died in the siege of Budapest in They did not discover their Jewish roots until they were adults. She was interviewing an old friend of her mother's who was a Holocaust survivor, when the woman suddenly said, "Of course, you know your grandparents were in one of the first transports to Auschwitz," where they perished. -

A Letter from the Editor Remembering Communism

OBERLIN COLLEGE RUSSIAN AND EAST EUROPEAN STUDIES AND OCREECAS REESNews 'BMMt7PMVNF Любовь в России: A Letter from the Editor BY COLLEEN CRONIN, OCREECAS INTERN, SPRING 2012 reetings to alumni and friends of Russian and Russian and East European studies (REES) at Oberlin. As many of you know, Oberlin College encourages students to study abroad by ofering an array of programs in multiple countries. Russian and GREES majors have the opportunity to study in various cities, both in Russia and in other post-soviet countries, an opportu- nity that was unheard of only 30 years ago! It was on one such program, at Bard-Smolny College in Saint Petersburg, that I met Alex Richardson ’12, with whom I fell in love and followed back to the green pastures of rural Ohio. From Saint Petersburg to Oberlin, we have shared many unique experiences. In Russia we saw icicles as big as people, tutored English at an orphanage, and introduced beer-pong to our native vodka-drinking comrades. Alex was even challenged to a duel by one of my suitors, which thankfully never took place. Afer returning to Oberlin, our adventures continued, thanks to the hard- working and thoughtful faculty members who welcomed me as one of their own students. Here, we saw a live performance of the Jerry Grcevich Tamburitza Orchestra, taught a Russian winter-term class, and read Master and Margarita in the original. Despite the lack of duels, Oberlin College has sponsored many culturally enriching events and has given me the honor of sharing them with you below. I hope you enjoy and appreciate them as much as I have. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E295 HON

March 14, 2000 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E295 Mr. Speaker, during my own years as a the removal of COMSAT's board and owner- takeover that followed. She and her parents New York State Assemblyman, Malcolm Wil- ship restrictions. Those restrictions are elimi- were able to escape to the West, and eventu- son served as a great inspiration and was of nated upon enactment without conditions. This ally she came to the United States. Kati is a immense assistance to our efforts. I can well change will enable Lockheed Martin to acquire journalist and author of the first rank. She cur- remember that his door was always open to 100% of COMSAT without further delay. I rently serves as the president of the Com- me or to any other legislator who sought his thank Chairman BLILEY and the other con- mittee to Protect Journalists, a nonpartisan assistance. ferees for amending this provision so that nongovernmental organization dedicated to In addition to being an outstanding public Lockheed Martin can more quickly enter the protecting journalists and press freedom servant, Malcolm Wilson was a courageous satellite communications market. throughout the world. She is also the author of veteran, having served in our Navy during I am also pleased that the conference Wallenberg: Missing Hero and Death in Jeru- World War II. He served on an ammunition agreement does not contain fresh look and so- salem. ship and participated in the invasion of Nor- called Level IV direct access, which would Mr. Speaker, I submit the text of Kati mandy. have been confiscatory and punitive. -

Author on Jewish Refugees Who Changed the World Comes to Carter Library Kati Marton to Discuss Her Book “The Great Escape” at Free Book-Signing

Jimmy Carter Library & Museum News Release 441 Freedom Parkway, Atlanta, GA 30307-1498 404-865-7100 For Immediate Release Date: Nov. 27, 2006 Contact: Tony Clark, 404-865-7109 [email protected] Release: NEWS06-43 Author on Jewish Refugees Who Changed the World Comes to Carter Library Kati Marton to Discuss Her Book “The Great Escape” at Free Book-Signing ATLANTA, GA.- Bestselling journalist Kati Marton tells the incredible stories of nine Hungarian Jews who fled from the Nazis and ended up having a major impact on the world at the Carter Presidential Library. Marton will speak and sign copies of her book “The Great Escape: Nine Jews Who Fled Hitler and Changed the World,” at 7:30 p.m. Monday, December 4th. The Carter Presidential Library lecture and book-signing is free and open to the public. Barnes and Noble will have copies of Marton’s book for sale at the event. Marton’s appearance is co-sponsored by the Georgia Center for the Book. Kati Marton The Great Escape: Nine Jews Who Fled Hitler and Changed the World Author Lecture & Book Signing 7:30 p.m. Monday, December 4th Carter Presidential Library Publishers Weekly writes “The nine illustrious Hungarians she profiles were all "double outsiders," for, as well as being natives of a "small, linguistically impenetrable, landlocked country," they were all Jews. Fleeing fascism and anti-Semitism for the New World, each experienced insecurity, isolation and a sense of perpetual exile. Yet all achieved world fame. The scientists Leo Szilard, Edward Teller and Eugene Wigner, along with game theorist and computer pioneer, John von Neuman, spurred Albert Einstein to persuade Franklin Roosevelt to develop the atomic bomb. -

Blumenstein to Address Scholars at OPC Foundation Awards Luncheon

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • January 2017 Blumenstein to Address Scholars at OPC Foundation Awards Luncheon By Jane Reilly challenges today,” he Rebecca Blumen- said. “She has come to stein, deputy editor-in- speak to our winners and chief of The Wall Street understands our program Journal, will be the key- very well. We are thrilled note speaker at the an- nual OPC Foundation that another major news Scholar Awards Lun- organization such as the cheon on Friday, Feb. 24, Journal has become a 2017, at the Yale Club. Rebecca Blumenstein (Continued on Page 4) She is the highest-ranking woman to lead the paper’s news organiza- Middle East tion to date has and also served as page-one editor, deputy managing Panel Set for editor, international editor and Chi- na bureau chief, overseeing China March Reunion coverage for the Journal. EVENT PREVIEW: March 1 Bill Holstein, president of the On March 1, the OPC and Inter- OPC Foundation, was especially national House will host a “Middle pleased to see Blumenstein head- East Hands Reunion” for foreign line the Foundation’s signature correspondents who covered the event. “Rebecca has earned her way to the top of a major news region. Deborah Amos, the OPC’s organization, having started out at first vice president, will moderate a regional newspapers and climbing panel to discuss the shifting geopo- the ladder at the Journal in part litical landscape and media cover- by living in China and winning a age in the wake of recent changes.